*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK 74118 ***

THE SEVEN MISSIONARIES

Jim Maitland Encounters Modern Pirates Aboard the “Andaman”

By Major H. C. McNeile

Illustrations by G. W. Gage

It never really got much beyond the rumor stage--Captain James Kelly of

the S. S. _Andaman_ saw to that. It wouldn’t have done him any good, or

his line, and since England was troubled with railway strikes and war

scares at Agadir, things which happened on the other side of the globe

were apt to be crowded out of the newspapers.

But he couldn’t stop the rumors, and “Our Special Correspondent” in

Colombo made out quite a fair story for his paper at home. It didn’t

appear; seemingly the editor thought the poor devil had taken to drink

and was raving. In fact, all that did appear in the papers were two

short and apparently disconnected notices. The first ran somewhat as

follows, and was found under the Shipping Intelligence:

“The S. S. _Andaman_ arrived yesterday at Colombo. She remained to carry

out repairs to her wireless, and will leave tomorrow for Plymouth.”

And the second appeared some two or three months after:

“No news has yet been heard of the S. Y. _Firefly_, which left Colombo

some months ago for an extensive cruise in the Indian Ocean. It is

feared that she may have foundered with all hands in one of the recent

gales.”

But she didn’t--the sea was as calm as the proverbial duck pond when the

S. Y. _Firefly_ went down in a thousand fathoms of water not far from

the Cocos Islands. And but for the grace of Heaven and Jim Maitland that

fate would have overtaken the good _Andaman_ instead.

And so for your eyes only, Mrs. Jim, I will put down the real facts of

the case. For your eyes only, I say, because I’m not absolutely sure

that legally speaking he was quite justified.

* * * * *

The S. S. _Andaman_ was a vessel of some three thousand tons. She was in

reality a cargo boat carrying passengers, in that passengers were the

secondary consideration. There was only one class, and the accommodation

was sufficient for about thirty people. Twelve knots was her maximum

speed, and she quivered like jelly if you tried to get more out of her.

And last, but not least, Captain James Kelly had been her skipper for

ten years, and loved her with the love only given to men who go down to

the sea in ships.

When Jim and I went on board she was taking in cargo, and Kelly was

busy. He was apparently having words with the harbor master over

something, and the argument had reached the dangerous stage of

politeness. But Jim had sailed in her before, and a minute or two later

a delighted chief steward was shaking hands with him warmly.

“This is great, sir!” he cried. “We got a wireless about the berths, but

we had no idea it was from you.”

“You can fix us up, Bury?” asked Jim.

“Sure thing, Mr. Maitland,” answered the other. “We’ve only got twelve

on board: two Yanks, a colored gentleman, two ladies and a missionary

bunch.” We had followed him below and he was showing us our cabins.

“Seven of ’em, sir,” he went on, “with two crates of Bibles and prayer

books, all complete. Maybe you saw them sitting around on deck as you

came on board.”

“Can’t say I did, Bury,” said Jim indifferently.

* * * * *

They never go ashore, sir,” continued the steward. “We’ve been making

all the usual calls, and you’d have thought they’d have liked to go

ashore and stretch their legs--but they didn’t. There they sit from

morning till night reading and praying, till they fairly give you the

hump.”

“It doesn’t sound like one long scream of excitement,” said Jim. “But if

they’re happy, that’s all that matters. Come on, Dick. Let’s go up and

see if old man Kelly is still being polite.”

We went on deck to find that the argument was finished, and with a shout

of delight the skipper recognized Jim. Jim went forward to meet him, and

for a moment or two I stood where I was, idly watching the scene on the

quay. And then quite distinctly I heard a voice from behind me say, “By

God! It’s Jim Maitland.” Now as a remark it was so ordinary when Jim was

about that I never gave it a thought. In that part of the world one

heard it, or its equivalent, whenever one entered a hotel or even a

railway carriage.

And so, as I say, I didn’t give it a thought for a moment or two, until

Jim’s voice hailed me, and I turned around to be introduced to the

skipper. It was then that I noticed two benevolent-looking clergymen

seated close to me in two deck chairs. Their eyes were fixed on the

skipper and on Jim, while two open Bibles adorned their knees. Not

another soul was in sight; there was not the slightest doubt in my mind

that it was one of them who had spoken. And as I stood talking with the

skipper and Jim my mind was subconsciously working.

There was no reason, of course, why a missionary should not recognize

Jim, but somehow or other one does not expect a devout man with a Bible

lying open on his knee to invoke the name of the Almighty quite so

glibly. If he had said “Dear me!” or “Good gracious!” it would have been

different. But the other came as almost a shock. However, the matter was

a small one, and probably I should have dismissed it from my mind, but

for the sequel a minute or two later. The skipper was called away on

some matter, and Jim and I strolled back past the two parsons. They both

looked up at us with mild interest as we passed, but neither of them

gave the faintest sign of recognition.

* * * * *

Now that did strike me as strange. A Clergyman may swear if he likes,

but why in the name of fortune he should utterly ignore a man whom he

evidently knew was beyond me.

“Come and lean over the side, Jim,” I said, when we were out of earshot.

“I want to tell you something funny. Only don’t look around.”

He listened in silence, and when I ended he said:

“More people know Tom Fool, old boy, than Tom Fool knows. I certainly

don’t know either of those two sportsmen, but it’s more than likely they

know me, at any rate by sight. And wouldn’t you swear if you had to wear

a dog collar in this heat?”

Evidently Jim was inclined to dismiss the episode as trifling, and after

a time I came around to the same view. Even at lunch that day, when the

skipper was formally introducing us and the clergyman still gave no sign

of claiming any previous acquaintance with Jim, I thought no more about

it. Possibly to substantiate that claim he might have had to admit his

presence in some place which would take a bit of explaining away to his

little flock. For the man whose voice I had heard was evidently the

shining light of the bunch.

He turned out to be the Reverend Samuel Longfellow, and his destination,

as that of all the others, was Colombo. They were going to open a

missionary house somewhere in the interior of Ceylon, and run it on

novel lines of their own. But at that point Jim and I got out of our

depths and the conversation languished. However, they seemed very decent

fellows, even if they did fail somewhat signally to add to the general

gaiety.

The voyage pursued its quiet, normal course for the first four or five

days. The two Americans and the skipper made up the necessary numbers

for a game of poker; the two ladies--mother and daughter they were by

the name of Armstrong--knitted; the seven parsons prayed, and the

colored gentleman effaced himself. The weather was perfect; the sea like

a mill pond with every prospect of continuing so for some time. And so

we lazed along at our twelve knots, making a couple of final calls

before starting on the two-thousand-mile run to Colombo.

* * * * *

It was the first night out on the last stage that Jim and I were sitting

talking with the skipper on the bridge. Occasionally the sharp, hissing

crackle of the wireless installation broke the silence, and through the

open door of the cabin we could see the operator working away in his

shirt sleeves.

“I guess it’s hard to begin to estimate what we sailors owe to Marconi

for that invention,” said Kelly thoughtfully. “Now that we’ve got it, it

seems almost incredible to think how we got along without it. And what

can I do for you, sir?”

An abrupt change in his tone made me look around to see the Reverend

Samuel Longfellow standing diffidently behind us. He evidently felt that

he was trespassing, for his voice was almost apologetic.

“Is it possible, captain, to send a message from your wireless?” he

asked.

“Of course it is,” answered Kelly. “You can hand in any message you like

to the operator, and he’ll send it for you.”

“You see, I’ve never sent a message by wireless before,” said the parson

mildly, “and I wasn’t quite sure what to do. Can you get an answer

quickly?”

“Depends on whom you are sending it to and where he is.”

“He’s on a yacht somewhere in this neighborhood,” answered the

clergyman. “He is a missionary, like myself, whose health has broken

down, and a kind philanthropist is taking him for a cruise to help him

recover. I felt it would be so nice if I could speak to him, so to

say--and hear from him, perhaps, how he is getting on.”

“Quite,” agreed the skipper gravely. “Well, Mr. Longfellow, there is

nothing to prevent your speaking to him as much as you like. You just

hand in your message to the operator whenever you want to, and he’ll

send down the answer to you as soon as he receives it.”

“Oh, thank you, Captain Kelly,” said the parson gratefully. “I suppose

there’s no way of saying where I am,” he continued hesitatingly. “I mean

on shore when one sends a wire the person who gets it can look up where

you are on a map, and it makes it so much more interesting for him.”

* * * * *

The skipper knocked the ashes out of his pipe.

“I’m afraid, Mr. Longfellow,” he remarked at length, in a stifled voice,

“that you can’t quite do that at sea. Of course, the position of the

ship will be given on the message in terms of latitude and longitude. So

if your friend goes to the navigating officer of this yacht, he’ll be

able to show him with a pin exactly where you were in the Indian Ocean

when the message was sent.”

“I see,” said the clergyman. “How interesting! And then, if I tell him

that we are moving straight toward Colombo at twelve knots an hour, my

dear friend will be able to follow me in spirit all the way on the map.”

The skipper choked slightly.

“Precisely, Mr. Longfellow. But I wouldn’t call it twelve knots an hour

if I were you. Just say--twelve knots.”

The Reverend Samuel looked a little bewildered.

“Twelve knots. I see. Thank you so much. I’m afraid I don’t know much

about the sea. May I--may I go now to the gentleman who sends the

messages?”

“By all manner of means,” said Kelly, and Jim’s shoulders shook. “Give

the operator your message, and you shall have the answer as soon as it

arrives.”

Again murmuring his thanks, the missionary departed, and shortly

afterward we saw him in earnest converse with the wireless operator. And

that worthy, having read the message and scratched his head, stared a

little dazedly at the Reverend Samuel Longfellow, obviously feeling some

doubts as to his sanity. To be asked to dispatch to the world at large a

message beginning “Dear Brother,” and finishing “Yours in the church”

struck him as being something which a self-respecting wireless operator

should not be asked to do.

“Poor little bird,” said the skipper thoughtfully, as the missionary

went aft to join his companions, “I’m glad for his sake that he doesn’t

know what the bulk of our cargo is this trip. He wouldn’t be able to

sleep at night for fear of being made to walk the plank by pirates.”

Jim looked up lazily.

“Why, what have you got on board, old man?”

The skipper lowered his voice.

“I haven’t shouted about it, Jim, and as a matter of fact I don’t think

the crew know. Don’t pass it on, but we’ve got over half a million in

gold below, to say nothing of a consignment of pearls worth certainly

another quarter.”

* * * * *

Jim whistled. “By Jove! It would be a nice haul for some one. Bit out of

your line, isn’t it, James--carrying specie?”

“Yes, it is,” agreed the other. “It generally goes on the bigger boats,

but there was some hitch this time. And it’s just as safe with me as it

is with them. That has made it safe.” He pointed to the wireless

operator busily sending out the parson’s message. “That has made piracy

a thing of the past. And incidentally, as you can imagine, Jim, it’s a

big feather in my cap, getting away with this consignment. It’s going to

make the trip worth six ordinary ones to the firm, and--er--to me. And,

with any luck, if things go all right, as I’m sure they will, I have

hopes that in the future it will no longer be out of our line. We might

get a share of that traffic, and I’ll be able to buy that chicken farm

in Dorsetshire earlier than I thought.”

Jim laughed. “You old humbug, James! You’ll never give up the sea.”

The skipper sighed and stretched himself.

“Maybe not, lad; maybe not. Not till she gives me up, anyway. But

chickens are nice companionable beasts they tell me, and Dorset is

England.”

* * * * *

We continued talking for a few minutes longer, when a sudden and

frenzied explosion of mirth came from the wireless operator. I had

noticed him taking down a message, which he was now reading over to

himself, and after a moment or two of unrestrained joy he came out on

deck.

“What is it, Jenkins?” said the skipper.

“Message for the parson, sir,” answered the operator.

“There is a duplicate on the table.”

He saluted, and went aft to find the Reverend Samuel.

“I think,” murmured the skipper, with a twinkle in his eye, “that I will

now inspect the wireless installation. Would you care to come with me?”

And this is what we, most reprehensibly, read:

Dear Brother how lovely the gentleman who guides our

ship tells me we pass quite close about midday the day

after tomorrow will lean over railings and wave pocket

handkerchief.

Ferdinand.

“My sainted aunt!” spluttered the skipper. “‘Lean over railings and wave

pocket handkerchief!’”

“I think I prefer ‘the gentleman who guides our ship,’ said Jim gravely.

“Anyway, James, I shall borrow your telescope as we come abreast of

Ferdinand. I’d just hate to miss him. Good night, old man. You’d better

have that message framed.”

It was about half an hour later that the door of my cabin opened and Jim

entered abruptly. I was lying in my bunk smoking a final cigarette, and

I looked at him in mild surprise. He was fully dressed, though I had

seen him start to take off his clothes twenty minutes before, and he was

looking grave.

“You pay attention, Dick,” he said quietly, sitting down on the other

bunk. “I had just taken off my coat when I remembered I’d left my cigar

case in a niche up on deck. I went up to get it, and just as I was

putting it in my pocket I heard my own name mentioned. Somewhat

naturally I stopped to listen. And I distinctly heard this

sentence--‘Don’t forget--you are absolutely responsible for Maitland.’ I

listened for about five minutes, but I couldn’t catch anything else

except a few disconnected words here and there, such as ‘wireless’ and

‘midday.’ Then there was a general pushing back of deck chairs, and

those seven black-coated blighters trooped off to bed. They didn’t see

me; they were on the other side of the funnel--but it made me think. You

remember that remark you heard as we came on board? Well, why the deuce

is this bunch of parsons so infernally interested in me? I don’t like

it, Dick.” He looked at me hard through his eyeglass. “Do you think they

are parsons?”

* * * * *

I sat up in bed with a jerk.

“What do you mean--do I think they’re parsons? Of course they’re

parsons. Why shouldn’t they be parsons?” But I suddenly felt very wide

awake.

Jim thoughtfully lit a cigar.

“Quite so--why shouldn’t they be? At the same time”--he paused and blew

out a cloud of smoke--“Dick, I suppose I’m a suspicious bird, but this

interest--this peculiar interest--in me is strange, to say the least of

it. Of course it may be that they regard me as a particularly black soul

to be plucked from the burning, in which case I ought to feel duly

flattered. On the other hand, let us suppose for a second that they are

not parsons. Well, I don’t think I am being unduly conceited if I say

that I have a fairly well-known reputation as a tough customer, if

trouble occurs.”

By this time all thoughts of sleep had left me.

“What do you mean, Jim?” I demanded.

He answered my question by another.

“Don’t you think, Dick, that that radiograph was just a little _too_

foolish to be quite genuine?”

“Well, it was genuine right enough. Jenkins took it down in front of our

eyes.”

“Oh, it was _sent_; I’m not denying that. And it was sent as he received

it, and as we read it. But was it sent by a genuine parson, cruising in

a genuine yacht for his health? If so, my opinion of the brains of the

church drops below par. But if”--he drew deeply at his cigar--“if, Dick,

it was not sent by a genuine parson, but by someone who wished to pose

as the driveling idiot curate of fiction, why, my opinion of the brains

of the church remains at par.”

“Look here,” I said, lighting a cigarette, “I may be stupid, but I can’t

get you. Granting your latter supposition, why should any one not only

want to pose as a parson when he isn’t one, but also take the trouble to

send fool messages around the universe?”

* * * * *

“Has it occurred to you,” said Jim quietly, “that two very useful pieces

of information have been included in those two fool messages? First, our

exact position at a given time, and our course and our speed. Secondly,

the approximate time when the convalescing curate, in the yacht

belonging to the kind friend, will impinge on that course. And the third

fact--not contained in either message, but which may possibly have a

bearing on things, is that on board this yacht there is half a million

in gold, and quarter of a million in pearls.

“Good heavens!” I muttered, staring at him foolishly.

“Mark you, Dick, I may have stumbled into a real first-class mare’s

nest. The Reverend Samuel and his pals may be all that they say and

more, but I don’t like this tender solicitude for my salvation.”

“Are you going to say anything to the skipper?” I asked.

“Yes,” he answered. “I think I shall tell James. But he’s a pig-headed

fellow, and he’ll probably be darned rude about it. I should, if I were

he. They aren’t worrying over _his_ salvation.”

And with that he went to bed, leaving me thinking fairly acutely. Could

there be anything in it? Could it be possible that any one would attempt

piracy in the twentieth century, especially when the ship, as the

skipper had pointed out, was equipped with wireless? The idea was

ridiculous, and the next morning I went around to Jim’s cabin to tell

him so. It was empty, and there was a note lying on the bed addressed to

me. It was brief and to the point:

I am ill in bed with a sharp dose of fever. Pass the

good news on to our friend--the parson. Jim

I did so, at breakfast, and I thought I detected a shade of relief pass

over the face of the Reverend Samuel though he inquired most

solicitously about the sufferer and even went so far as to wish to give

him some patent remedy of his own. But I assured him that quinine and

quiet were all that were required, and with that the matter dropped.

And then there began for me a time of irritating suspense. Not a sign of

Jim did I see for the whole of that day and the following night. His

cabin door had been locked since I went in before breakfast, and I

didn’t even know whether he was inside or not. All I did know was that

something was doing, and there are few things more annoying than being

out of a game that you know is being played. Afterward I realized that

it was unavoidable; but at the time I cursed inwardly and often.

* * * * *

And the strange thing is that when the thing did occur it came with

almost as much of a shock to me as if I had had no previous suspicions.

It was the suddenness of it, I think--the suddenness and the absolute

absence of any fuss or shouting. Naturally I didn’t see the thing in its

entirety; my outlook was limited to what happened to me and in my own

vicinity.

I suppose it was about half-past eleven, and I was strolling up and down

the deck. Midday had been the time mentioned, and I was feeling excited

and restless. Mrs. Armstrong and her daughter were seated in their usual

place, and I stopped and spoke a few words to them. Usually Mrs.

Armstrong was the talker of the two--a big, gaunt woman with yellow

spectacles, but pleasant and homely. This morning, however, the daughter

answered--and her mother, who had put on a veil in addition to the

spectacles, sat silently beside her.

“Poor mother has such a headache from the glare that she has had to put

on a veil,” she said. “I hope Mr. Maitland is better.”

I murmured that he was about the same, just as two of the parsons

strolled past and I wondered why the girl gave a little laugh. Then

suddenly she sat up, with a cry of admiration.

“Oh, look at that lovely yacht!”

I swung around quickly, and there, sure enough, about a hundred yards

from us and just coming into sight around the awning, was a small steam

yacht, presumably the one from which Ferdinand was to wave. And at that

moment the shorter of the two parsons put a revolver within an inch of

my face, while the other one ran his hands over my pockets. It was so

unexpected that I gaped at him foolishly, and even when I saw my Colt

flung overboard I hardly realized that the big holdup had begun.

* * * * *

Then there came a heavy thud from just above us, and I saw Jenkins, the

wireless man, pitch forward on his face half in and half out of his

cabin door. He lay there sprawling, while another of the parsons

proceeded to wreck his instruments with the iron bar which he had used

to stun the operator. Just then, with a squawk of terror like an

anguished hen, Mrs. Armstrong rose to her feet, and with her pink

parasol in one hand and her rug in the other fled toward the bow of the

ship. She looked so irresistibly funny--this large, hysterical

woman--that I couldn’t help it, I laughed. And even the two

determined-looking parsons smiled, though not for long.

“Go below,” said one of them to Miss Armstrong. “Remain in your cabin.

And you”--he turned to me--“go aft where the others are.”

“You infernal scoundrel!” I shouted. “What are you playing at?”

“Don’t argue, or I’ll blow out your brains,” he said quietly. “And get a

move on.”

I found the two Americans and the colored gentleman standing in a bunch

with a few of the deck hands, and every one seemed equally dazed. One of

the so-called parsons stood near with a revolver in each hand, but it

was really an unnecessary precaution; we were none of us in a position

to do anything. And suddenly one of the Americans gripped my arm.

“Gee! Look at the two guns on that yacht.”

* * * * *

Sure enough, mounted fore and aft, and trained directly on us were two

guns that looked to me to be of about three-inch calibre, and behind

each of them stood two men.

“What’s the game anyway?” he went on excitedly, as two boats shot away

from the yacht. For the first time I noticed that the engines had

stopped and that we were lying motionless on the calm, oily sea. But my

principal thoughts were centered on Jim. Where was he? What was he

doing? Had these blackguards done away with him, or was he lying up

somewhere--hidden away? And even if he was, what could he do? Those two

guns had an unpleasant appearance.

A bunch of armed men came pouring over the side of the ship, and then

disappeared below, only to come up again in a few minutes carrying a

number of wooden boxes, which they lowered into the boats alongside.

They worked with the efficiency of well-trained sailors, and I found

myself cursing aloud. For I knew what was inside those boxes, and was so

utterly helpless to do anything. And yet I couldn’t help feeling a sort

of unwilling admiration; the thing was so perfectly organized. It might

have been a well-rehearsed drill, instead of a unique and gigantic piece

of piracy.

I stepped back a few paces and looked up at the bridge. The skipper and

his three officers were there--covered by another of the parsons. And

the fifth member of the party was the Reverend Samuel Longfellow. He was

smiling gently to himself, and as the last of the boxes was lowered over

the side, he came to the edge of the bridge and addressed us.

“We are now going to leave you,” he remarked suavely. “You are all

unarmed, and I wish to give you a word of advice. Should either of the

gunners on my yacht see any one move, however innocent the reason,

before we are on board, he or both of them will open fire. So do not be

tempted to have a shot at me, Captain Kelly, because it will be the last

shot you ever have. You will now join your crew, if you please.”

* * * * *

In silence the skipper and his officers came down from the bridge, and

the speaker followed them. For a moment or two he stood facing us with

an ironical smile on his face.

“Your brother in the church thanks you for your little gift to his

offertory box,” he remarked. Then he turned to one of the other parsons

beside him. “Is it set?” he asked briefly.

“Yea,” said the other. “We’d better hurry. What about that woman up

there?”

“Confound the woman!” answered the Reverend Samuel. “A pleasant journey,

Captain Kelly.”

He stepped down the gangway into the second boat, and was pulled away

toward the yacht. And, feeling almost sick with rage, I glanced at the

skipper beside me. Poor devil! What he must be feeling, I hardly dared

to think. To be held up on the High Seas and robbed of specie and pearls

the first time he was carrying them was cruel luck. And I was prepared

to see anything on his face, save what I did see. For he was staring at

the bow of the ship, with a fierce blaring excitement in his eyes, and

instinctively I looked too, though every one else was staring at the

yacht.

And then for the first time I remembered Mrs. Armstrong. She was

cowering down with her hands over her ears--the picture of abject

terror. But now curiosity overcame her fright, and she knelt there,

staring at the yacht. Her pink parasol was clutched in her hands; and

tragic though the situation was, I could not help smiling involuntarily.

Anyway, she would have something to talk about when she got home.

A mocking shout from the yacht made me look away again. The scoundrel

who called himself the Reverend Samuel Longfellow was standing beside

the boxes of gold and pearls which had been stacked on the deck. He was

waving his hand and bowing ironically, with the six other blackguards

beside him, when the last amazing development took place.

Literally before our eyes they vanished in a great sheet of flame. I had

a momentary glimpse of the yacht apparently splitting in two, and then

the roar of a gigantic explosion nearly deafened me.

“Get under cover!” yelled the skipper, and there was a general stampede,

as bits of metal and wood began falling into the sea all around us. Then

there came another smaller explosion as the sea rushed into the yacht’s

engine room, a great column of water shot up, and when it subsided the

yacht had disappeared.

“What in heaven’s name happened?” said one of the Americans dazedly.

“What made her blow up like that?”

I said nothing; I felt too dazed myself. And unconsciously I looked

toward the bow: Mrs. Armstrong had disappeared.

* * * * *

The skipper sent away a boat, but it was useless.

There was a mass of floating wreckage, but no trace of any survivor, and

after a while the search was given up. Just one of those unexplained

mysteries which in this case could only be accounted for as Divine

retribution.

So, at any rate, Mrs. Armstrong said to me when I met her on deck half

an hour afterward.

“Dreadful! Terrible!” she cried. “How more than thankful I am that I

didn’t see it.”

“You didn’t see it?” I said, staring at her. “But surely----”

And then I heard Jim’s voice behind me.

“Mrs. Armstrong, I have a dreadful confession to make. Mrs. Armstrong,

Dick, was good enough to lend me some clothes this morning, so that we

could have a rag when crossing the line--and I’ve gone and dropped her

parasol overboard.”

I admit it; I wasn’t bright.

“We’re nowhere near the line,” I remarked, but fortunately the good lady

paid no attention.

“What does it matter, Mr. Maitland?” she cried. “To think of anything of

that sort in face of this awful tragedy! Though I must confess I think

it served the villains right.”

She walked away like an agitated hen, and Jim smiled grimly.

“Poor old soul,” he said, “let’s hope she never finds out what I really

wanted her clothes for.”

“So it was you up in the bow,” I remarked.

He nodded. “Didn’t you guess? Dick, I feel I’ve treated you rather

scurvily. Let’s go and have a drink and I’ll put you wise. I saw Kelly

that night,” he began, when we were comfortably settled, “and at first

he laughed as I thought he would. Then after a while he didn’t laugh

quite so much, and later still he stopped laughing altogether. Finally I

made a suggestion. If these men were what they said they were, the two

big chests below, which common report had it were filled with Bibles,

would prove their case. I suggested, therefore, that we examine these

two chests. They would never know, and it would settle the matter. He

took a bit of persuading, but finally we went below to where the

passengers’ luggage is stored. There were the two cases, and there and

then we opened one. It was packed--not with Bibles--but with

nitroglycerin.”

Jim paused and took a drink, then lit a cigarette thoughtfully.

“I don’t think that I have ever seen a man in quite such a dreadful rage

as Kelly was,” he went on gravely. “There was a clockwork mechanism

which could be started by turning a screw on the outside of each box,

and the whole diabolical plan was as clear as daylight. There was enough

stuff there to sink a fleet of battleships, and when they had cleared

off in the yacht with the gold we should suddenly have split in two and

gone down with every soul on board. There would have been no one left to

tell the tale, and these cold-blooded murderers would have got clean

away. That was the little plot.”

He smiled grimly.

“I had no small difficulty in preventing James from putting the whole

bunch in irons on the spot, but finally I got him to agree to a plan of

mine. We changed the cargo around--he and I. Their chests containing

nitroglycerin we filled with gold; and the specie boxes we filled with

nitroglycerin and some lead and iron as a make-weight. And then we let

the plan proceed. We banked on a holdup and the wrecking of the

wireless. We thought they’d send over a boatload of armed men, and

transfer the stuff to the yacht--and in fact they did. Further, we

banked on the fact that they wouldn’t fool around with a fat, hysterical

old woman, or a man in the throes of fever. Good girl--that Miss

Armstrong; she kept her mother below all the morning in great style. And

that, I think, is all,” he ended, with a quizzical glance at me.

“But it isn’t!” I cried. “What made that stuff blow up, if it had been

taken out of the boxes with the clockwork mechanism?”

“Well, old Dick,” said Jim, “it may be that the Reverend Samuel kicked

one of the boxes a trifle hard in his jubilation. Or perhaps he dropped

his Corona inadvertently. Or maybe something hit one of those boxes very

hard like a bullet from a gun. Come down to my cabin,” he added,

suddenly.

I followed him and he shut the door. On the bed was lying Mrs.

Armstrong’s pink parasol. The muzzle of an Express rifle stuck out

through a hole that had been split in the silk near the ferrule; the

stock was hidden by the material. Jim took it out and cleaned it

carefully. Then he looked at the parasol and smiled.

“Beyond repair, old man. And since I told the old dear I had dropped her

gamp overboard--well--”

He rolled it up slowly and threw it far out through the porthole, then

stood for a moment watching it drift.

[Transcriber’s Note: This story appeared in the October 1923 issue of

McClure’s Magazine.]

*** END OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK 74118 ***

The seven missionaries

Download Formats:

Excerpt

Jim Maitland Encounters Modern Pirates Aboard the “Andaman”

By Major H. C. McNeile

Illustrations by G. W. Gage

It never really got much beyond the rumor stage--Captain James Kelly of

the S. S. _Andaman_ saw to that. It wouldn’t have done him any good, or

his line, and since England was troubled with railway strikes and war

scares at Agadir, things which happened on the other side of the globe

were apt to be crowded out of the newspapers.

But he couldn’t stop the rumors, and...

Read the Full Text

— End of The seven missionaries —

Book Information

- Title

- The seven missionaries

- Author(s)

- McNeile, H. C. (Herman Cyril)

- Language

- English

- Type

- Text

- Release Date

- July 25, 2024

- Word Count

- 5,982 words

- Library of Congress Classification

- PR

- Bookshelves

- Browsing: Crime/Mystery, Browsing: Fiction

- Rights

- Public domain in the USA.

Related Books

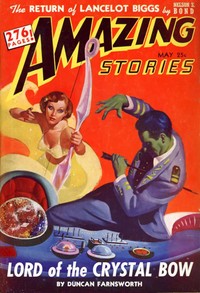

The crystal planetoids

by Coblentz, Stanton A. (Stanton Arthur)

English

441h 21m read

Famous stories from foreign countries

English

494h 26m read

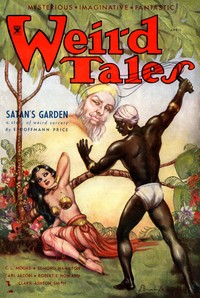

Terror out of the past

by Gallun, Raymond Z., Gallun, Raymond Z. (Raymond Zinke)

English

247h 56m read

Corsairs of the cosmos

by Hamilton, Edmond

English

152h 39m read

The incredible slingshot bombs

by Williams, Robert Moore

English

96h 4m read

The young naval captain

by Stratemeyer, Edward

English

700h 5m read