*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK 74629 ***

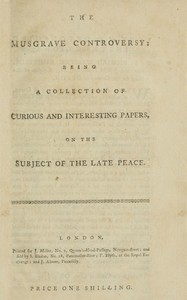

THE

MUSGRAVE CONTROVERSY:

BEING

A COLLECTION OF

CURIOUS AND INTERESTING PAPERS,

ON THE

SUBJECT OF THE LATE PEACE.

LONDON,

Printed for J. Miller, No. 2, Queen’s-Head-Passage, Newgate-street;

and sold by S. Bladon, No. 28, Paternoster-Row; F. Blyth, at the

Royal Exchange; and J. Almon, Piccadilly.

PRICE ONE SHILLING.

COPY of the DEVONSHIRE INSTRUCTIONS.

To Sir RICHARD WARWICK BAMPFYLDE, Bart. and JOHN PARKER, Esq; Knights of

the Shire for the County of DEVON.

We, the Freeholders of the County of Devon, assembled in a General

Meeting at the Castle of Exon, find ourselves called upon by many weighty

considerations to exercise the constitutional and unquestionable right

of instructing our Members with regard to their conduct in Parliament.

It becomes now more highly necessary, when an opinion has been publickly

avowed, derogatory from that relation which ought to subsist between the

Electors and their Representatives. We, therefore, enjoin you to promote

and support an enquiry into all those grievances that have so justly

alarmed the subjects of this kingdom; particularly, for what reasons a

magistrate, in the immediate service of the Crown, to whom informations

of the most important nature were imparted by a native and Freeholder of

this County, refused to examine or enquire after the evidence pointed

out to him; being a person the most capable of clearing up the affair,

both from his own knowledge, and the papers _then_ in his possession;

in consequence of which refusal, secrets of the most important nature

to the safety of this kingdom have been probably lost, and the alledged

instruments of dishonour to his Majesty’s government _screen’d_ from

censure and punishment; and that you will diligently pursue an enquiry

into the criminal transactions referred to in that information; and

that you also use your utmost endeavours to shorten the duration of

Parliaments.

Voted at the Castle of Exon, Oct. 5, 1769.

THE MUSGRAVE CONTROVERSY,

_An ADDRESS to the Gentlemen, Clergy, and Freeholders of the County of

Devon, preparatory to the General Meeting at Exeter on Thursday the 5th

of October, 1769._

By Dr. MUSGRAVE, _Physician at Plymouth_.

GENTLEMEN,

The sheriff having summoned a meeting of the county in order to consider

of a Petition for redress of grievances, I think it incumbent on me as a

lover of my country in general to lay before you a transaction, which,

I apprehend, gives juster grounds of complaint and apprehension than

any thing hitherto made public. Having long had reason to imagine that

the nation has been cruelly and fatally injured in a way which they

little suspect, I have ardently wished for the day, when my imperfect

information should be superseded by evidence and certainty. That day, I

flatter myself, is at last approaching, and that the spirit which now

appears among the Freeholders will bear down every obstacle that may be

thrown in the way of open and impartial enquiry.

I need not remind you, Gentlemen, of the universal indignation and

abhorrence, with which the conditions of the late peace were received by

the independant part of the nation. Yet such is the candid, unsuspecting

nature of Englishmen, that even those who condemned the measure did not

attribute it to any worse motive than an unmanly impatience under the

burdens of the war, and a blind, headlong desire to be relieved from

them. They did not conceive that persons of high rank and unbounded

wealth could be seduced by gold to betray the interests of their country,

and surrender advantages, which the lives of so many heroes had been

willingly sacrificed to purchase. Such a supposition, unhappily for us,

is at present far from incredible. The important secret was disclosed to

me in the year 1764, during my residence at Paris. I will not trouble

you with a detail of the intermediate steps I took in the affair,

which, however, in proper time I shall most fully and readily discover.

It is sufficient to say, on the 10th of May 1765, by the direction of

Dr. Blackstone I waited on Lord Halifax, then Secretary of State, and

delivered to him an exact narrative of the intelligence I had received

at Paris, with copies of four letters to and from Lord Hertford. The

behaviour of Lord Halifax was polite but evasive. When I pressed him in

a second interview to enquire into the truth of the charge, he objected

to all public steps that might give an alarm, and asked me whether I

could point out to him any way of prosecuting the enquiry in secret, and

whether in so doing there was any probability of his obtaining positive

proof of the fact. I was not so much the dupe of his artifice as to

believe that he had any serious intention of following the clue I had

given him, though his discourse plainly pointed that way. It appeared by

the sequel that I had judged right. For having four days after given a

direct and satisfactory answer to both his questions, he then put an end

to my solicitations by a peremptory refusal to take any steps whatever in

the affair.

It is here necessary to explain what I mean by enquiring into the truth

of the charge. In the summer of the year 1764, an overture had been

made to Sir George Yonge, Mr. Fitzherbert, and several other Members

of Parliament, in the name of the Chevalier D’Eon, importing that he,

the Chevalier, was ready to impeach three persons, two of whom are

Peers and Members of the Privy Council, of selling the peace to the

French. Of this proposal I was informed at different times by the two

gentlemen above-mentioned. Sir George Yonge in particular told me that

he understood the charge could be supported by written as well as living

evidence. The step that I urged Lord Halifax to take, was to send for

the Chevalier D’Eon, to examine him upon the subject of this overture,

to peruse his papers, and then to proceed according to the proofs. In

such a case a more decisive evidence than the Chevalier D’Eon could not

be wished for. He had the negociation on the part of the enemy, and was

known to have in his possession the dispatches and papers of the Duke de

Nivernois. This gentleman, so qualified and so disposed to give light

into the affair, did Lord Halifax refuse to examine; whether from an

apprehension that the charge would not be made out, or on the contrary

that it could. I leave you, gentlemen, and every impartial reader to

judge.

It must not be understood, that I can myself support a charge of

corruption against the noble Lords named in my information. My complaint

is of a different nature and against a different person. I consider the

refusal of Lord Halifax as a willful obstruction of national justice,

for which I wish to see him undergo a suitable punishment. Permit me to

observe, gentlemen, that such an obstruction not only gives a temporary

impunity to offenders, but tends also to make that impunity perpetual, by

destroying or weakening the proofs of their guilt. Evidence of all kinds

is a very perishable thing. Living witnesses are exposed to the chance

of mortality, and written evidence to the not uncommon casualty of fire.

In the present case something more than these ordinary accidents might

with good reason be apprehended. It stands upon record that the Count de

Guerchy had conspired to assassinate the Chevalier D’Eon, neither has

this charge hitherto been refuted or answered. This not succeeding, a

band of ruffians was hired to kidnap that gentleman, and carry off his

papers. Though this second attempt failed, it does not follow that these

important papers are still secure. I was informed by Mr. Fitzherbert,

so long ago as the 17th of May, 1765, that he had then intelligence

of overtures making to the Chevalier D’Eon, the object of which was

to get the papers out of his hands in return for a stipulated sum of

money. This account I communicated the following day to Lord Halifax,

who still persisted in exposing those precious documents to so many

complicated hazards. I say precious documents, because if they should be

unfortunately lost, the affair must be for ever involved in uncertainty,

an uncertainty, gentlemen, which may be productive of infinite mischiefs

to the nation, and cannot tend to the advantage or satisfaction of any

but the guilty.

Lord Halifax, in excuse for his refusal, will probably alledge, as he did

to me, his persuasion that the charge was wholly groundless. I need not

observe, how misplaced and frivolous such an allegation is when applied

to justify a magistrate for not examining evidence. But I will suppose

for argument’s sake the persons accused to be perfectly innocent. Is it

not the interest and the wish of every innocent man to have his conduct

scrutinized while facts are recent, and truth, of consequence, easy to

be distinguished from falshood? Is there any tenderness in suffering

a stain to remain upon their characters till it becomes difficult, or

even impossible to be wiped out? Will therefore these noble persons,

if their actions have been upright, will they, I say, thank Lord

Halifax for depriving them of an early opportunity of establishing

their innocence? Will they not regret and execrate his caution, if the

subsequent suppression or destruction of the evidence should concur

with other circumstances to fix on them the suspicion of guilt? How

will Lord Halifax excuse himself to his Sovereign, for suffering so

attrocious a calumny to spread and take root, to the evident hazard of

his royal reputation? And what amends will he make to the nation for the

heart burnings and jealousies which are the natural fruits of such a

procedure? Yet these, gentlemen, are the least of the mischiefs that may

be apprehended from his behaviour upon the footing of his own plea.

I will venture however to assert, that, as far as hitherto appears,

the weight of evidence and probability is on the contrary side. Now,

supposing the charge to be true, there can be no need of long arguments

to convince you of the injury done to the nation, by suffering such

capital offenders to escape. For what is this but to defraud us of

the only compensation we can expect for the loss of so many important

territories, a loss rendered still more grievous by the indignity of

paying a pension, as we notoriously do, to the foreign ministers who

negociated the ruinous bargain? Yet even these considerations are

infinitely out-weighed by the danger to which the whole nation must be

exposed from the continued operation of so much authority, influence,

and favour to their prejudice, and, above all, from the possibility that

the supreme government of the kingdom may, by the regency-act, devolve

to a person directly and positively accused of high treason. Even the

encouragement that such an impunity must give to future treasons, is

enough to fill a thinking mind with the most painful apprehensions. We

live in an age, not greatly addicted to scruples, when the open avowal of

domestic venality seems to lead men, by an easy gradation, to connexions

equally mercenary with foreigners and enemies. How then can we expect

ill-disposed persons to resist a temptation of this sort, when they find

that treason may be detected, and proofs of it offered to a magistrate,

without producing either punishment or enquiry? The consequence of

this may be, our living to see a French party, as well as a court

party, in parliament; which, should it ever happen, no imagination can

sufficiently paint the calamitous and horrid state to which our late

glorious triumphs might finally be reduced. When I talk of a French party

in parliament, I do not speak a mere visionary language unsupported

by experience. The history of all ages informs us, that France, where

other weapons have failed, has constantly had recourse to the less

alarming weapons of intrigue and corruption. And how effectual these

have sometimes been, we have a recent and tragical example in the total

enslaving of Corsica.

I have been thus particular in enumerating the evils that may result

from the refusal of Lord Halifax, not from a desire of aggravating that

nobleman’s offence, but merely to evince the necessity of a speedy

enquiry, while there is yet a chance of its not being wholly fruitless.

Though the course of my narrative has unavoidably led me to accuse his

Lordship, accusation is not my object, but enquiry, which cannot be

disagreeable to any but those to whom truth itself is disagreeable.

In pursuing this point, I have hitherto been frustrated from the very

circumstance which ought to have insured my success, the immense

importance of the question. It has been apprehended, how justly I

know not, that any magistrate, who should commence an enquiry, or any

gentleman who should openly move for it, would be deemed responsible for

the truth of the charge, and subjected to severe penalties, if he could

not make it good. This imagination, however, did not deter me, though

single and unprotected, from carrying my papers to the Speaker, to be

laid before the late House of Commons. The Speaker was pleased to justify

my conduct, by allowing, that the affair ought to be enquired into, but

refused at the same time to be instrumental in promoting the enquiry

himself. What then remained to be done? What, but to wait, though with

reluctance and impatience, till a proper opportunity should offer for

appealing to the public at large, that is, till the accumulated errors of

government should awaken a spirit of enquiry too powerful to be resisted

or eluded? That this spirit is now reviving, we have a sufficient earnest

in the unanimous zeal you have shewn for the appointment of a county

meeting. In such a conjuncture, to withold from you so important a truth,

would no longer be prudence, it would be to disgrace my former conduct,

it would shew that I had been actuated by some temporary motives, and not

by a steady and uniform regard to national good. Indeed, the declared

purpose of your meeting is in itself a call upon every freeholder to

disclose whatever you are concerned to know. I obey this call without

hesitation, submitting the prosecution of the affair to your judgment, in

full confidence that the result of your deliberations will do honour at

the same time to your prudence, candour, and patriotism.

_Plymouth, Aug. 12, 1769._

_Reponse du Chevalier D’Eon a la lettre que M. le DOCTEUR MUSGRAVE a

fait imprimer dans le Public Advertiser du 2 Sept. 1769, No. 10869, &

qui a ensuite ete copiee dans tous les autres papers, sous la datte de

Plymouth, le 12 Aout, &c._

MONSIEUR,

Vous me permettrez de croire que vous ne m’avez jamais plus connu, que

je n’ai l’honneur de vous connoitre: & si dans votre lettre du 12 Aout

vous n’aviez pas abuse de mon nom, je ne me verrois pas force d’entrer en

correspondence avec vous.

Vous pretendez que “dans l’ete de 1764, on fit des ouvertures en mon nom

a differens membres du parlement, portantes que j’etois pret a accuser

trois personnes, donc deux etoient pairs, et membres au conseil prive,

d’avoir vendu la paix a la France;” & vous paroissez fonder la dessus

l’evidence de l’accusation, que vous dites en avoir porte vous memes a

Milord Halifax.

Je vous declare en consequence ici Monsieur, que je n’ai jamais ni fait

faire aucune ouverture pareille, ni dans l’hiver, ni dans l’ete de 1764,

ni dans aucun tems. Je suis d’une part trop fidele au ministere que j’ai

rempli, et de l’autre trop zelateur de la verite.

J’avoue que vous ne dites pas que ce soit moi qui aie fait ces

propositions: Mais seulement qu’elles ont ete fait en mon nom,

specialement a M. le Chevalier George Yonge & a M. Fitzherbert.

Je vous assure ne connoitre aucun de ces Messieurs & n’avoir jamais

authorise qui que ce soit a faire, en mon nom, de pareilles ouvertures,

que mon horreur seule pour la calomnie me feroit detester.

Je vous interpelle donc, M. le Docteur, de declarer au public le nom du

temeraire qui s’est servi du mien pour faire ces ouvertures odieuses.

Ces Messieurs que vous avez denonce comme vos temoins, ne peuvent vous

refuser de venger leur veracite & la votre.

Quoique je ne puisse m’empecher de louer votre droiture qui cite ses

auteurs, cependant il me paroit de la derniere imprudence, dans une

affaire d’une pareille gravite, de vous fonder sur un raport pour

nommer publiquement un homme de mon caractere, sans l’avoir auparavant

consulte. Si vous vous etiez souvenu du dementi que j’ai donne dans le

S. James’s Chronicle du 25 Octobre 1766, No. 881, a un avertissement du

meme papier, No. 875, qui portoit en substance ce que vous alleguez dans

votre derniere lettre, vous m’auriez epargne la peine de vous repondre

aujourdhui. Qu’en va-t-il arriver? Le public aura lu avidement votre

lettre, aura ajoute foi a son contenu parceque vous en appellez a mon

evidence: Mais qu’en pensera t-il maintenant? quand votre interet, mon

honneur & la verite m’obligent a nier ce que vous y avancez a mon sujet.

Il en est de meme de ce que vous pretendez que “vers le 17 Mai 1765, M.

Fitzherbert vous auroit dit savoir qu’on m’avoit fait des propositions de

vendre pour une somme d’argent les papiers qui etoient entre mes mains.”

Je me suis toujours flatte de l’estime & de l’amitie des Anglois avec

lesquels j’ai vecu. Qui d’eux dans ces sentimens auroit ose me temoigner

assez de mepris pour me faire une pareille proposition? L’injure m’en

auroit ete d’autant plus sensible que le caractere de la personne auroit

ete plus respectable.

Je ne vous suivrai, Monsieur, ni dans les demarches que vous avez cru

devoir faire, ni dans les raisonnemens dont vous vous servez pour les

appuier: Ceux-ci montrent l’orateur & celles-la, si elles sont fondees,

preuvent le patriote. Mais je vous atteste ici, sur ma parole d’honneur &

a la face du public, que je ne puis vous etre d’aucune utilite, que je ne

suis jamais entre en marche pour la vente de mes papiers, & que je n’ai

jamais, ni par moi-meme ni par aucun agent autorise de ma part, propose

de fait voir que la paix avoit ete vendue a la France.

Si Milord Halifax, ou l’orateur, auxquels vous dites vous etre addresse

pour m’appeller en temoignage sur la validite de votre accusation,

m’avoient fait citer; ils auroient connu par mes reponses que je pense

que l’Angleterre a plutot donne de l’argent a la France, que la France de

l’or a l’Angleterre pour conclure la derniere paix et que le bonheur que

j’ai eu de concourir au salutaire ouvrage de cette paix m’a inspire les

sentimens de la plus juste veneration pour les commissaires Anglois qui

y ont ete emploies, & ceux de la plus vive estime & de la plus sincere

admiration pour feu M. le Comte de Viry qui, par son attachement pour le

bien des deux nations belligerantes & graces a son zele infatiguable, eut

la gloire d’amener cette paix necessaire aux deux nations a une heureuse

conclusion. Jugez maintenant, Monsieur, avec quelle solidite vous pouvois

vous fonder sur moi pour rendre votre accusation evidente!

Je suis trop connu en Angleterre pour avoir eu besoin de cette reponse,

si la franchise de votre lettre me n’avoit paru meriter que je vous

empechasse de faire des demarches ulterieures qui ne pouroient tourner

qu’a votre prejudice, puis qu’elles ne seroient fondees que sur de faux

raports de mes actions. Pour vous mettre a meme d’etre aussi prudent que

patriote, je signe cette lettre & vous y donne mon addresse, afin que,

pour soutenir votre veracite, vous me donniez les moiens de convaincre

publiquement les calomniateurs, qui ont ose se servir de mon nom, d’une

maniere plus contraire encore a la verite des faits, qu’a la dignite

avec lequelle, J’ai toujours soutenu mon caractere au millieu meme de la

persecution de mes enemis.

J’ai l’honneur d’etre votre tres humble serviteur,

LE CHEVALIER D’EON.

_In Petty-France, Westminster, 4 Septembre, 1769._

_Translation of the Chevalier ~D’Eon~’s Answer to Dr. ~Musgrave’s~

Address._

SIR,

You will permit me to believe that you never knew any more of me, than

I have the honour of knowing of you: and if in your letter of the 12th

of August you had not made a wrong use of my name, I should not now find

myself obliged to enter into a correspondence with you.

You pretend that “in the summer of the year 1764, overtures were made in

my name to several members of parliament, importing that I was ready to

impeach three persons, two of whom were peers and members of the privy

council, of having sold the peace to the French:” and you seem to found

thereupon the evidence of a charge, which you say you carried yourself to

Lord Halifax.

I declare, therefore, here, Sir, that I never made, nor caused to be

made any such overture, either in the winter or summer of the year 1764,

nor at any other time: I am, on one side, too faithful to the office I

filled, and on the other too zealous a friend to truth.

I confess you do not say it was I that made these overtures; but only

that they were made in my name, particularly to Sir George Yonge and Mr.

Fitzherbert.

I assure you I do not know either of these gentlemen, and never

authorised any person whatever to make in my name such overtures, which

the abhorrence alone I have for calumny, would make me detest.

I call upon you, therefore, Sir, to lay before the public the name of the

audacious person who has made use of mine to cover his own odious offers.

The gentlemen whom you have given as your witnesses, cannot deny you this

justification of their own veracity and your’s.

Though I cannot but commend your integrity in citing your authors,

yet it appears to me an act of the last imprudence, in an affair of

so much weight, to build upon report, for naming publickly a person

of my character, without having previously consulted him. If you had

recollected the contradiction I gave in the St. James’s Chronicle of

Oct. 25, 1766, No. 881, to an advertisement in the same paper, No.

875, importing in substance what you alledge in your last letter, you

had saved me the trouble of replying to you at this time. What must be

the result? The public will have read greedily your letter; will have

believed it’s contents, because you appeal therein to my testimony: but

what will they think now when your own interest, my honour and truth

oblige me to deny all that you have advanced thereon with respect to me.

It is the same with your pretence that “about the 17th of May, 1765, Mr.

Fitzherbert told you, he knew that overtures had been made to me to sell

for a sum of money the papers that were in my hands.”

I have always flattered myself with being possessed of the esteem and

friendship of the English with whom I have lived. Who of them then in

these sentiments would have presumed to have shewn sufficient contempt

for me to have made me such an overture? The injury would have been

the more sensibly felt by me, as the character of the person was more

respectable.

I shall not follow you, Sir, either in all the steps you have thought it

your duty to take, or in the arguments you made use of to support them:

these shew the orator, and those, if they be well founded, prove the

patriot.

But I here certify to you, on my word of honour, and in the face of the

public, that I cannot be of any sort of use to you; that I never entered

into any treaty for the sale of my papers, and never either by myself or

any agent authorised on my part, offered to make appear, that the peace

had been sold to France.

If Lord Halifax, or the Speaker, to whom you say you addressed yourself

in order to call upon me as evidence, with respect to the validity of

your charge, had caused me to be cited, he might have known by my answers

what my thoughts were, that England rather gave money to France than

France to England, to conclude the last peace; and that the happiness

I had in concurring to the great work of peace has inspired me with

sentiments of the justest veneration for the English commissioners who

had been employed in it, and with the most lively esteem and sincerest

admiration for the late Count de Viry, who in his attachment to the

welfare of the two nations then at war, and thanks to his indefatigable

zeal! had the glory of bringing that peace to a happy conclusion.

Judge now, Sir, with what solidity you can depend upon me to make your

charge clear.

I am too well known in England to have been under any necessity of this

reply, if the frankness of your letter had not appeared to me to merit my

preventing you from taking any further steps, which could not but turn

to your prejudice, in as much as they would be founded solely on false

reports of _my_ proceedings.

In order to enable you to be as prudent as patriotic, I sign this letter,

and therein give you my address, that for the maintenance of your own

veracity you may furnish me with the means of convicting publickly those

slanderers who have dared to make use of my name, in a manner still

more repugnant to real facts, than the dignity with which I have ever

supported my character.

I have the honour of being your most humble servant,

_The Chevalier D’EON._

_In Petty France, Westminster._

_To Charles-Genevieve-Louis-Auguste-Andre-Timothee ~D’Eon de Beaumont~,

Chevalier de l’ordre roial & militaire de S. Louis,[1] Ministre

Plenipotentiare de France aupres du Roi de la Grande Bretagne, Captaine

de Dragons au service de sa Majeste tres Chretienne, Avocat au Parlement

de Paris, Censeur roial pour l’Histoire et les Belles Lettres en France,

&c._

LETTER I.

SIR,

I have read with particular attention your letter to Dr. Musgrave, and

can no longer be in doubt what your business at present is in a country

where you are an _outlaw_.

You exhibit to us a character most singularly profligate. You alone in

this age have had it in your power to be equally false and treacherous

to two such great nations as England and France. While you were

only secretary to the Duke of Nivernois, you abused the privileges

of your character, and engaged in the dirty business of _debauching

our manufacturers_. You so entirely forgot the dignity of your rank

afterwards, when Minister Plenipotentiary, that you continued the same

practice, although it is contrary to the law of nations. You do not

even blush to charge this article of expence in the state of your

disbursements to the Comte de Guerchy. “Avance aux ouvriers Anglois

de la manufacture de toiles peintes, tant hommes que femmes, debauche

par le Sieur _L’Escalier_ a Londres et des environs pour les faire

passer ailleurs 195l.” Lettres, Memoires, &c. p. 172. The meanness and

rascality of such an employment in you and Monsieur _L’Escalier_ can

only be equalled by the tameness and ignominy of the administration at

that time in suffering _L’Escalier_, a notorious pimp and an _outlaw_

here, to be after this in the public character of _Secretary_ of the

Comte de Guerchy. The attestations of _L’Escalier’s outlawry_ were

printed here, witnessed by Solomon Schomberg, a Notary Public, and by

the Lord Mayor. They were dispersed at the Hague, to serve the purpose

of shewing at a certain juncture that England was bullied by France. You

afterwards quarrelled with all your best friends, as well as with the

ministers of your fortune, and your own Court, which had raised you so

rapidly from nothing, from being a writer to the police at Paris on the

pension of 600 livres, or 25 guineas a year, to the dignity of Minister

Plenipotentiary at the most important Court in Europe. Modern times

scarcely produce an instance of political treachery equal to your’s in

printing the secrets of the Court by whom you were employed, and the

private letters of your benefactor the Duke of Nivernois, of Monsieur

Sainte-Foy, Monsieur Moreau, &c. Your particular quarrel with Guerchy

had nothing to do with the sentiments of the Duke of Nivernois, of

Mess. Sainte-Foy, Moreau, and other gentlemen, on the conduct of the

French parliament, the administration of their finances, &c. which were

intrusted to you, as their private friend, under the seal of secrecy.

You betrayed their confidence without the least provocation on their

part, or a pretence of justification of your own conduct from any one

circumstance in those letters. After quarrelling with almost all your

own countrymen, you published in the same volume a gross abuse of this

nation, and called the English a parcel of fools and madmen, at the

very time that this country afforded you an honourable protection, and

an hospitality you have abused. “Apres deux secousses de tremblement

de terre, qui arriverent ici en 1750, _un soldat enthousiaste_ s’avisa

d’en predire un troisieme, qui devoit renverser Londres. Il se dit

inspire, & d’un ton enthousiaste en fixa le jour, l’heure, & la minute.

Londres consterne au souvenir des deux secousses qui s’etoient suivies

dans l’intervalle d’un mois, & plus effraie encore a l’approache d’un

troisieme & plus terrible tremblement que ce soldat enthousiaste avoit

annonce pour le 5 d’Avril, la ville s’est montree susceptible de toutes

sortes d’impressions. Plus de 50 mille habitans, sur la foi de cet

oracle, avoient ce jour-la pris la fuite: la plupart de ceux que les

raisonnemens ou les raillerie de leurs amis avoient retenue, attendoient

en tremblant l’instant critique, & n’ont montre de courage qu’apres qu’il

a ete passe. Le jour arrive, la prophetie, semblable a la plupart des

predictions, ne fut point accomplie; le faux Samuel fut mis un peu tard

aux petites maisons & _la tete de ces fiers insulaires si senses & si

philosophes ne fut pas a l’epreuve de la prophetie d’un fou_.” P. 14. I

believe there is not to be found so gross and silly an abuse of a whole

nation for the weakness of a few hysteric women, and superannuated men,

nor so false a representation of any fact. Were your other dispatches

to your court, Sir, composed of such wretched stuff as this? I hope the

_bottle-conjurer_ finds his place in the second part of your _memoires_.

That innocent joke of the late Duke of Montague, your countrymen

generally talk and write of as a serious proof of the folly and credulity

of this nation. The English laughed at your weak attack on them as a

nation, and superior to such abuse, desired that you might continue to

enjoy the protection of their noble system of laws, and the privileges

of their country. They considered their own glory, not the worthlessness

of the individual. They would have parted with so insignificant a wretch

as you without the least regret; but they would not suffer you to be

forced away, nor kidnapped, merely because it would have been an outrage

to their laws, and the honour of their nation. They too, as politicians,

thought you might be induced to make some discoveries, and were ready

to profit by your treason to your own country in the secrets you might

reveal for the benefit of their’s, but at the same time they would have

abhorred the traitor. When I mention the English nation as anxious for

your safety, I mean the body of the people. The administration _at that

time_ wished that you might be carried off to France. Mansfield and

Norton saw Guerchy often on the occasion, and Sandwich signed more than

one warrant to apprehend you. The French ministry, and the people here

in power at that time, planned your destruction; but the generosity of

two or three individuals saved you, and preserved a viper in the bosom of

their country. Now is just the season for such noxious reptiles to come

forth. They always meet the approaching storm. Leagued with the enemies

of our country, whether French or English, your slender abilities are

still employed against a nation you hate, but in your heart honour and

revere. After having for some years talked very openly of the wonderful

discoveries you could make, and the impeachment you could support, after

frequently declaring, that _you had two heads in your pocket_, when a

worthy gentleman steps forth and states the charge, you at once recoil,

and declare that you do not even believe a word of it, but think that

_l’Angleterre a plutot donne de l’argent a la France, que la France de

l’or a l’Angleterre pour conclure la derniere paix_. So absurd an idea

I shall not undertake to refute, because I believe you are the only man

_at large_, who entertains it; but I shall in this first address to you,

desire you to state _two_ facts to the public, relative to the subject

of your letter to Dr. Musgrave. The _first_ is, What was the negociation

relative to the island of _Porto-Rico_? The Duke of Bedford set out for

Paris, Sept. 5, 1762. Every thing of importance was soon entirely settled

between the two courts. The most material arrangements had been made here

in private with Lord Bute before his Grace’s departure. The news of the

taking the Havannah was afterwards first received in England, while the

Duke was in Paris, on Sept. 29. Now I ask what alteration in the terms

of the treaty did such important intelligence produce? What was to be

given England, additional to the former stipulations, in consequence

of the surrender of the Havannah, when that likewise was to be given

up? You are called upon to state that transaction; what you know of the

ten days cession of Porto Rico to us by the negociation at Paris, and

the subsequent surrender of that island on the receipt of _two_ letters

from hence, one of which the Duke of Bedford ought to produce for his

justification in _that part_ of the business; the other is too sacred to

appear. The _second_ question I shall now ask is, _whether you have not

declared that you were offered 7000 louis for your papers?_ Your letter

to Dr. Musgrave is extremely evasive on this head. You say, “Je me suis

toujours flatte de l’estime & de l’amitie _des Anglois_ avec lesquels

j’ai vecu. _Qui d’eux_ dans ces sentimens auroit ose me temoigner

assez de mepris pour me faire une pareille proposition?” No, Sir, _no

Englishman_ was employed in so dirty a business; but one of your own

country was found to make the proposition, to which you objected. You

said the sum was too trifling for papers of such importance. My other

letters shall give the world more truths; for I will drag you forth to

the public view, not merely as a trifling Frenchman, trifling in every

thing serious, and serious only in trifles, but as the enemy of England,

as a pensioned tool of a wicked ministry, who hope by your means to

trifle or perplex an enquiry, which may not stop at your patron, the

detested _Thane_, to whom, although a Frenchman, you have sacrificed the

great _Sully_ in the most fulsome and lying of all dedications, prefixed

to your pirated _Considerations Historiques & Politiques sur les Impos_.

Your connections, Sir, are at length discovered, and the plan of your

operations, so secretly concerted by Bute’s three deputies, Jenkinson,

Dyson, and _Target_ Martin, at a house in Pall Mall, which governs this

kingdom, shall be given to the public. You will experience, that although

English generosity makes us always ready to give refuge and protection to

a distressed foreigner, even from the country of our inveterate enemies,

we will not suffer among us a French traitor and a spy, in the pay of

an administration odious to this whole nation. I shall only at present

add, that one of your friends will soon prove to you that your own poet

_Corneille_ says very truly,

_Et meme avec justice on peut trahir un traitre._

I am, Sir,

An ENGLISHMAN.

_Sept. 11, 1769._

[1] The Chevalier D’Eon began in this manner the affidavit he made Dec.

28, 1764, although his public character had been superseded by the French

King, and declared at an end by the King of England, above a year before.

LETTER II.

_To the Chevalier ~D’Eon~._

SIR,

The warm applause you give to the peace of Paris, and the negociators

of it, both English and French, did not in the least surprise me. You

were well paid for it at the time, and the private advantages derived

to you from it did not cease with its _ratification_. The peace itself

was in its own nature so infamous, and so peculiarly _felonious_ to this

country, which it robbed of almost all its noble conquests, that no

Englishman was judged proper to be sent with the authentic ratification

of such a French bargain. It was given to you _contre toute regle &

contre toute usage_, as the Duke de Praslin says in your _Memoires_;

and the Duke of Nivernois observes in a letter to the Duke of Bedford,

that it was _une galanterie de votre ministere, & une bonte du Roi votre

maitre, qui se sert avec plaisir D’UN FRANCOIS pour cette tournure_.

Besides, at the very time of the negociation you held the Ambassador’s

pen; and altho’ you were never entrusted with the most important secrets

between the two courts, you were employed in the revisal of that fatal

instrument which tore from our bleeding warriors the fruits of all their

victories, the greatest acquisitions your rival nation had ever made.

You are allowed to have much chicanery; and the tricking article about

the Canada Bills was the effect of your duping the Duke of Bedford,

and the good-humoured Mr. Neville. You may therefore with reason speak

of the peace of Paris in terms of rapture, as a Frenchman, and as the

Duke of Nivernois’s secretary. I will ever mention it with indignation;

for I am an Englishman, and have not that load of guilt to expiate to

my country, the advising, making, or _approving_ so ruinous a measure.

You are, however, Sir, by no means singular in your opinion of the

late _peace_ even in this nation. We too have many traitors among us.

A set of gentlemen at Westminster gave an _entire approbation_ of the

_preliminary articles_, even with the very extraordinary original clause

about the East-India Company among them. Their bankers best know how

that _approbation_ was obtained; but their successors, altho’ careless

about the national debt, have had the prudence as well as foresight for

themselves, to pay off all debts contracted on that account.

You speak with some degree of modesty concerning yourself when you

mention the peace of Paris, as if conscious that you had only been

employed to toll the bell for the funeral of England’s departed glory

and fame. When you mention Count _Viry_, you are quite lavish in his

praises, knowing how much he had been a principal in that accursed

treaty. I respect the dead; but only the departed virtuous and good. I

distinguish characters, notwithstanding the trite maxim of _de mortuis

nil nisi bonum_. I will never confound a Cato and a Cataline, but will

give to each their due. I execrate the memory of Count Viry, as the

enemy of my country, as having been a principal in robbing England of

the _Havannah_, PORTO RICO, _Martinique_, _Guadelupe_, _Desiderade_,

_Mariegalante_, _St. Peter_, _Miquelon_, _Goree_, _Belleisle_, _St.

Lucia_, _&c._ and negociating a treaty which has proved the salvation

of France. I believe you have, besides the general cause of the peace,

which saved France, two particular reasons for the regard you testify

to the memory of Count Viry. The first is the very dexterous management

he used to get the claim of a sugar island from France waved, in which

you knew she was ready to have acquiesced. The other is, the protest he

signed in favour of the House of Savoy, which he procured to be legally

attested and given in at the time of the last coronation, in the name

of his master, the present King of Sardinia. He too in your time had

printed the _Genealogie de la Famille Royale d’Angleterre_, by which he

hoped at a future day that the ridiculous claims of his master’s family,

as being, although Papists, immediately descended from Henrietta Maria,

the daughter of Charles I. would have prevailed over those of the House

of Brunswick, who are descended from Elizabeth, Electress Palatine, one

degree more remote from the Crown, as being the daughter of James I. You

both expected at least a general confusion speedily among us; but neither

you, nor he, born under arbitrary governments, could have any idea of the

only lawful right to the crown of these realms, a parliamentary right.

The contrary doctrine was in Queen Anne’s time expresly declared to be

_high treason_, by a particular statute, the “Act for the better securing

her Majesty’s person and government, and the succession to the crown of

England in the protestant line;” _That if any person or persons, from

and after the 25th day of March 1706, shall maliciously, advisedly and

directly, by writing or printing, declare, maintain, or affirm that the

Kings or Queens of England, with and by the authority of the parliament

of England, are not able to make laws and statutes of sufficient force

and validity to limit and bind the crown of this realm, and the DESCENT,

LIMITATION, INHERITANCE, and government thereof, every such person or

persons shall be guilty of High Treason, and being thereof convicted and

attainted, &c. &c._ Count Viri acted by the express orders of his Court,

in conjunction with your’s. In the same manner the two Courts acted

in concert at the beginning of this century, in the last year of our

glorious Deliverer, King William III. Count Maffei, the Ambassador from

Savoy, delivered in the first famous protestation, in the name of the

Duchess of Savoy, against the Hanover succession, at the time the Duke

himself commanded the French army in Italy, with Marshal Catinat and the

Prince of Vaudemont under him, and every action of his life was dictated

by France. I believe you therefore _unusually_ sincere, when you express,

“la plus vive estime & la plus sincere admiration pour feu Monsieur le

Comte de Viry, qui par son attachement pour le bien des deux nations

belligerantes & graces a son zele infatiguable, eut la gloire d’amener

cette paix necessaire aux deux nations a une heureuse conclusion.” What

this _happy conclusion_ for England was, we have already seen. From that

fatal moment France, like a tall bully, began again to lift the head, and

insult all its neighbours.

You tell Dr. Musgrave, “le public aura lu avidement votre lettre, aura

adjute foi a son contenu parceque vous en appellez a mon evidence.” You

are mistaken. Your evidence of itself will have little weight with any

one, but you may have papers of importance, which the public expected

from _your own absolute promise_. The last page of your tiresome quarto

promised a second volume on the first of June 1764, and a third the first

of September. You ought to have given them at the stipulated time, and

to have made them as valuable as you could from the materials of others,

were it only to indemnify us for having waded through the family dullness

and impertinence of the letters to your mother, nurse, &c. &c. What did

the Scot give you for the suppression? Was it as much as you had for the

dedication, in which you tell him that you find “dans les portraits du

Duc de Sully & de Milord Bute une ressemblance assez parfaite, de grandes

vertus, l’amour de la patrie (_Scotland I suppose_) de la philosophie; la

profondeur d’un politique, l’eloquence d’un homme d’etat, cette activite

d’esprit qui donne les succes & les revers, ce coup d’œil qui demele les

objets meme au milieu du trouble, qui fait le grand negociateur, &c. &c.”

Upon my word you merited the whole sum he gave you, let it have been

ever so considerable. But did you believe one single feature of _Bute_

was like _Sully_? I am satisfied no more than your master the Duke of

Nivernois, Ambassador and Academician, one of your _quarante immortels_,

believed that the Kings of England and France were _faits pour s’aimer,

formed to love each other_, although he declared so at St. James’s with

the utmost gravity, and afterwards printed it, like a compliment of the

French Academy, only in both French and English for the amusement of

the two nations. The flattery of the French ambassador and secretary

succeeded. The English monarch and his Scottish minister were equally

captivated; and the most gallant army in Europe were left to regret that

they had not once the honour even of a visit from our sovereign during

the whole war, or before they were disbanded. The early and dangerous

intrigues, the specious flattery of a home favourite, and an insinuating

foreign minister, but above all the holding out in such terms, _le

charactere distinctif d’une bonne foi non equivoque_, at which the King

of Prussia has so much laughed, lulled asleep all heroism, suspicion, and

even curiosity.

You are very just, Sir, in the observation, that the public read with

great eagerness Dr. Musgrave’s letter. The reason is plain. The fact,

that French gold made the last peace, was long ago believed; but the

public rejoiced when a man of Dr. Musgrave’s unblemished reputation

stated the presumptive evidence in general terms to his countrymen of

Devonshire, because then it seemed impossible any longer to stifle the

enquiry. You say, “Je vous interpelle donc, M. le Docteur, de declarer

au public le nom du temeraire qui s’est servi du mien pour faire ces

ouvertures odieuses.” The Doctor does not say that he ever heard the

name of the person, who, _in your name_, applied to Sir George Yonge,

Mr. Fitzherbert, and several other members of parliament. He only

declares that Sir George Yonge and Mr. Fitzherbert informed him _at

different times_ that _an overture had been made IN THE NAME of the

Chevalier d’Eon, importing that he, the Chevalier, was ready to impeach

three persons, two of whom are peers and members of the privy council,

of selling the peace to the French_. Why do you not make your appeal to

these two gentlemen? If neither of the placemen should chuse to answer,

if they are either fearful or false, if the _boards of admiralty and

trade_ have exacted at least a promise of secrecy, I will name a third

person to you, a character unexceptionable, of a candour, probity, and

honour equal to Dr. Musgrave’s, superior I believe never existed. I mean

Thomas Cholmondeley, Esq; the late member for Cheshire, a relation of

Lord Chatham. My reason for naming this gentleman you will see in the

following passage. “It is true (_Pitt_) assisted in the first debate

upon General Warrants in 1764; but finding that some of the party were

in earnest in their designs of going farther, and had prepared a motion

against the seizure of papers, which was, in fact, the great grievance;

and also finding that the _favourite_ dreaded the minority gaining a

victory, lest the party should be afterwards turned against him; and

that the _favourite_ had therefore supported the administration with all

his might upon this occasion, the great patriot scandalously withdrew

from the cause and the party; thereby _preventing_ any point being

then gained towards that security of public liberty, which the whole

kingdom so ardently wished for and expected. A short time afterwards,

when an IMPEACHMENT OF THE FAVOURITE was privately rumoured among a few

only; and it was said, that there was strong evidence ready to be given,

_particularly with regard to the peace_; when a certain baronet, and

others, who took some pains in order to come at this evidence, and the

conditions upon which it might have been obtained were trifling, not

pecuniary (_the pardon of the Chevalier D’Eon is here meant_) and who

thought it necessary that the great Commoner should be consulted upon a

subject of such importance, especially too as he was looked upon to be

the fittest person to lead, or principally support such a procedure; and

when, in consequence of that idea, he was applied to by one of his own

friends, and, in some measure, a distant relation, he checked the whole

in the bud, by declaring vehemently against it.” _An enquiry into the

conduct of the late Right Honourable Commoner_, page 26, _&c._ published

in 1766. The strange phrase _Pitt_ used was, _that he would set his

foot on the head of the man who first moved the enquiry, and crush him

to atoms_. I am very glad to hear that the _three brothers_ are at last

united, and that there is now not only a family, but a political union

among them. I venture however to prophesy, that two of the three will

never promote an enquiry into the transactions of the last _peace_, or

the conduct of the _favourite_, and I therefore hope all the friends of

the public will be on their guard against them both. They cannot safely

be trusted with the conduct of this important business. The _apostate_

had in 1764 his peerage and place of Privy Seal in view, for which he

then sold his friends and his country. He now looks forwards to a more

lucrative office, a larger pension to recruit his shattered finances,

and perhaps to a higher title, which he may probably get, if he can keep

the favourite’s head on his shoulders. I wish however the _triumvirate_

of brothers success, because I think a _triumvirate_, which should be

only insolent and overbearing, is infinitely to be preferred to a sole

minister who is cruel; and _delights in blood_.

I should before this, Monsieur le Chevalier, have apologized to you

for the frankness of my proceeding with respect to you, and the plain

language of my heart, but really my nature is open and undisguised. I

detest flattery and foolish compliments. I call things generally by their

names, _j’appelle un chat un chat, et rolet un fripon_. Besides your

example ought to weigh in an address to you. The embassador extraordinary

and plenipotentiary of your court, a Cordon Bleu, who represented the

person of the Most Christian King, you repeatedly in the grossest manner

call _ane extraordinaire_, and you add, _la truye n’ennoblit pas le

cochon_. Monsieur Bussy, the late French minister here, is with you a

_bourreau_. Your language even to your own mother is particularly rude.

You advise a tender affectionate parent, in tears for the misconduct

of a son she loved, to _wipe her eyes, plant her cabbages, weed her

garden, eat her greens, and drink the milk of her cows and the wine of

her vineyard_, without giving herself any trouble about you. The letter

to your nurse, Madame Benoit a Tonnerre, is rather more obliging. You

talk of all her _soins et peines passees_, and then very elegantly add,

that _you are well at present, but should be better if you could see

her soon_. To her you act the _signor magnifico_; you actually send her

one hundred livres, or near four pounds and eight shillings sterling.

How interesting is all this to the public? how glorious to you? But to

return to your poor mother, whom I heartily pity. You tell her in return

for her concern, that you have read _toutes les lettres lamentables et

pitoyables que vous avez pris la peine de m’ecrire: pourquoi pleurez

vous, femme de peu de foi?_ You make use here, Sir, of our Blessed

Saviour’s words in a very strange and indecent manner. You speak of him

in your last publication, _in a most daring and really impudent stile_.

In the _Pieces Authentiques_, page 13, your words are, _on n’accusa point

Jesus Christ au Banc d’Herode d’avoir debite des libelles; cependant ce

que notre seigneur a avance n’a jamais ete si bien prouve que ce que le

Chevalier D’Eon a demontre par ses LETTRES ET MEMOIRES. Jesus Christ was

not accused at Herod’s Bench of having published libels; although what

our Saviour advanced was never so well proved as what the Chevalier D’Eon

has demonstrated in his LETTERS AND MEMOIRS._ After all these instances I

shall conclude without the least compliment to you, with only saying, that

I am, Sir,

An ENGLISHMAN.

To the PRINTER.

Lord B. and his toad eater the D. of G. both knew the contents of Dr.

Musgrave’s letter many weeks before it made its appearance. They had

concerted many schemes to suppress its publication; but all these

schemes, however artfully managed, proved abortive. Lord B. who came

fresh from the school of politics at Rome, embraced still the same

propensity for absolute monarchy as he did before he departed from

England. He is grown, indeed, more cautious, more masked, but not a jot

less enterprising. Foiled in his well-concealed attempts to prevent the

publication of Dr. Musgrave’s letter, his next attempt was to render the

publication of it inoperative and ineffectual. The difficulty lay in

compassing this desirable end. He knew very well that one ******** had

married a cast-off, who formerly held no mean rank in his toad eater’s

seraglio: this same ********, his Lordship knew had been confidently

intrusted at different times, with the most important secrets of Mr.

Wilkes, the Chevalier D’Eon, and Lord Temple, and therefore the only

fit person to be confidentially entrusted, as far as his Lordship might

deem necessary, with the opening a negociation for a treaty of union

between the Earls of B—e, T——e, E———t, C———m, Lord H———d, and the

petulant Duke of B———. Such a coalition, with his toad eater at the

head, he rightly conceived, would be able to stem any torrent of

opposition, were it to roll mountains high. But his Lordship, it will

be seen, counted without his host. His first intention was to dispatch

******** to Stow. This measure could not be carried into execution but

by another mode of application. ******** had already forfeited Lord

T——e’s confidence, but he did not care to acquaint either G. or B. with

this secret, which could not but be fatal to his own views; he therefore

artfully declined going to Stow himself, adding, that the embassy would

have greater weight, and probably better success, was the D. of G. to

wait in person on Lord T———. ******** pretended to know the very bait

that would tempt his Lordship; it was nothing less than a Dukedom, and

if he ********, was to make the offer, Lord T———e, he said, might doubt

the performance. By this device and advice of ********, B. and his toad

eater were easily betrayed into a fond belief of gaining over Lord T. to

their faction. Accordingly, the D. of G. was posted down to Stow, and

this truly courtly visit was immediately announced in every news-paper

throughout the kingdom. The success of this visit is no longer a mystery.

The wild, incoherent, crude plan of operations, were conveyed, without

loss of time, to Fonthill, and from Fonthill it soon arrived at Plymouth.

Dr. Musgrave finding this once formidable and blood-thirsty faction

tottering, and failing of support from Lord T. thought it a glorious

opportunity to crush the whole junto, by hanging them out to public view

and public odium. With this view, and to do justice to a brave, but

greatly injured people, the Doctor, with a courage not to be daunted,

published that well-timed letter, which has already unfilm’d the eyes of

every subject in the kingdom, and which, in a few days, will receive a

further elucidation from

_The_ BRITISH SPY.

To the PRINTER.

In my former letter I furnished your readers with an anecdote relative

to Mr. ********. This man, who is connected with his Grace the D. of G.

by the apron-string tenure; the present modish, and by much the strongest

of all holds, has been constantly and most secretly employed for these

last six weeks, as a go-between to the D. of G. and the Soi-disant

l’Homme de Charactere, M. D’Eon.

To throw a veil over this mysterious negociation, and in order to blind

the eyes of the prying public, the pretty Frenchman who lives in Petty

France, has for this fortnight past been roaring out in every coffee-house

he frequents, that Mr. ********, the go-between above-mentioned, has

betrayed his most sacred secrets to the D. of G. and the whole B———d

junto. This flimsy, gausy device, was no sooner made public, but it was

seen through by every tyro in politics. And the Frenchman was compelled

by his new employers to lay aside the mask. He was ordered by this new

sett of masters, who will always tyrannize over him in proportion to

the pension they give him: he was ordered I say flatly to deny every

circumstance in Dr. Musgrave’s patriotic letter, and boldly to assert,

“that he never entered into any treaty for the sale of his papers.”

Nothing is so easy to a Frenchman, especially if they have been once

initiated into the diplomatic corps, as to assert one thing for another,

where they know they cannot for the present moment be detected. But

what will the good people of England think of the veracity of this same

Frenchman, when I call upon him in this public manner to declare for

what reason, at whose instigation, and for what valuable consideration

in money, he suppressed the publication of _those three letters_ relative

to the late peace-makers?

I know, Mr. Printer, I speak ænigmatically to the generality of your

readers, when I talk of three letters. But the D. of B———d understands

me; Lord B—— understands me; and D’Eon, if he has any regard for truth,

ought to blush at the bare mention of those three letters. There is

but one moral tie can bind a French gentleman, that is, his word of

honour. Let D’Eon then, if he dare, lay his hand upon his Croix de St.

Louis, and swear, upon his _honour_, that he never received directly

or indirectly, without equivocation, or mental reservation, any money,

pension, emolument, or promise, for suppressing the publication of the

three letters in question, and he shall either be credited, or publickly

confuted, by

_The_ BRITISH SPY.

To the PRINTER.

Doctor Musgrave’s address to the freeholders of the county of Devon,

and the Chevalier D’Eon’s answer to it, having engrossed the public

attention, give me leave, first, to consider the nature and tendency of

the address, and then to make a few remarks on the Chevalier’s answer.

Mr. Musgrave has told us a series of facts within his own knowledge,

the authenticity of which are corroborated by the names of the parties

concerned, and the periods in which they were transacted. He tells us,

that Sir George Yonge, Mr. Fitzherbert, and other members of parliament,

informed him at different times, that the Chevalier D’Eon was really to

impeach three persons of selling the peace to the French—that Sir George

Yonge in particular told him, that he understood the charge could be

supported by written as well as by living evidence. By the direction of

Dr. Blackstone, Mr. Musgrave went to Lord Halifax _on the 10th of May,

1765_, and delivered to him an exact narrative of the intelligence he

had received at Paris concerning the late peace, and at the same time

gave him copies of four letters to and from Lord Hertford. _On the 17th

of May, 1765_, just seven days after he delivered the narrative to Lord

Halifax, Mr. Fitzherbert told the Doctor, that overtures were then making

to the Chevalier D’Eon to get his papers from him for a stipulated sum of

money. Lord Halifax, although repeatedly pressed by Doctor Musgrave to

enquire into the truth of the charge, first, objected to all public steps

that would lead to the truth, to avoid giving _an alarm_; and, at last,

absolutely refused to take any cognizance of it, either in private or

public. Thus frustrated in every application to the secretary of state,

the Doctor carried his papers to the Speaker, who very readily allowed

the expediency of their being laid before the House of Commons, but at

the same time peremptorily refused to promote the enquiry.

This, Sir, is the substance of Dr. Musgrave’s address, which carries with

it such a face of authenticity, that nothing but a public investigation

of the facts can exculpate the parties concerned. As to the tendency of

it, every unprejudiced reader must allow, that the public good, and not

an inclination to aggravate the guilt of any particular person, was his

object.

If the allegations contained in the address are not fairly stated—if

Doctor Musgrave has been guilty of injuring private characters, and

of imposing falshoods on the public—why, in God’s name, is he not

contradicted?—Why do not the accused exculpate themselves?—Why are not

the public undeceived?—Why should _they_ be silent whose conduct is

principally arraigned, and a vindication, such as it is, be published by

a man, whose veracity in this respect is by no means to be relied on? For

when his papers were purchased from him, the condition of the obligation

no doubt was, that their contents should be buried in oblivion.

When the official conduct of a secretary of state, or of any other

servant of the crown, is arraigned, the public have an undoubted right

to be satisfied either of their guilt or innocence, in order that the

law of the land may in either case take effect. When the character of

an honest man is unjustly and publicly attacked, he will not postpone

the vindication of his innocence until a legal enquiry can be set on

foot in a court of law; he ought to exculpate himself through the same

channel he has been accused. Therefore, until Doctor Blackstone tells us

the conversation that passed between him and Mr. Musgrave, previous to

his waiting on Lord Halifax—Until Lord Halifax informs us whether Doctor

Musgrave did or did not deliver to him a narrative of the intelligence he

had received at Paris, concerning the peace in 1764, and likewise publish

the copies of the four letters to and from Lord Hertford; which, as

they are of a public nature, his _politeness_ need not stumble at—Until

Sir George Yonge and Mr. Fitzherbert publicly deny every circumstance

relative to their several conversations with Doctor Musgrave, especially

what passed between Mr. Fitzherbert and him _on the 17th day of May,

1765_—And until the Speaker acquaints us with the reason why he allowed

the expediency of laying these important papers before the House of

Commons, and at the same time _refused to promote the enquiry_—Until all

these matters are promulged and sufficiently authenticated, the impartial

and dispassionate part of mankind must and will give credit to the facts

contained in the address.

I come now, Sir, to make a few remarks on the Chevalier D’Eon’s answer,

which I shall do with the same impartiality I have considered the

address, and leave the public to draw the line between the honest

sincerity of the Englishman, and the evasive _finesse_ of the Frenchman.

Monsieur le Chevalier, notwithstanding his long residence in England,

and the esteem and friendship he is favoured with from _some_ of the

inhabitants (the reason of which he knows best) still preserves his

_native_ insincerity and politeness. His letter to Dr. Musgrave is as

foreign to the purpose of an answer to the address, as the conduct of

our present ministry in suffering his master, the Grand Monarque, to

conquer Corsica, was foreign to the faith of treaty, and repugnant to the

interest of this kingdom—than which no two positions can be more opposite.

The Chevalier has very _politely_ passed some French compliments on

the doctor’s oratory and patriotism—has talked a good deal of his own

integrity and zeal for truth—blames him for naming a person of his _vast_

consequence in so public a manner, and manfully denies every circumstance

he is publicly known to have been concerned in at the time mentioned

in the address. But what does all this amount to with respect to Mr.

Musgrave’s allegations? He, indeed, very justly says, that the evidence

of the Chevalier would have been decisive at the time he urged Lord

Halifax to send for him to examine him, and to peruse his papers which

he _then_ had in his possession; but in his address to the freeholders of

Devon, he neither desires nor expects any proofs from him _now_, because

he either knows, or shrewdly suspects, that no written evidence is now to

be found in his custody.

The Chevalier desires to know the person or persons in this country,

who would have presumed to make an overture to him for the sale of his

papers—I wish to God I could tell him!—or rather that I could tell the

public—for the Chevalier himself, I dare say, wants no information in

that affair. It is much to be wished, however, that Lord Halifax or the

Speaker had examined the Chevalier, and that it might at least have

been known what sum was paid by England, and for what consideration it

was given to France, at the conclusion of the last ever memorable and

glorious peace.

TULLIUS.

LETTER I.

To Dr. MUSGRAVE, of PLYMOUTH.

SIR,

The meritorious and intrepid manner in which you have stepped forth, and

called the public attention to the negociation of the last infamous

peace, deserves the thanks and applause of your country. As an individual

of this country, not wholly unacquainted with some parts of that

negociation, you have my poor thanks: but thanks alone are not sufficient

in such a cause; I should hold myself the basest of Englishmen, if I

did not contribute my mite towards accomplishing a full and impartial

enquiry into the manner in which that important work was conducted. Such

parts of the negociation as have accidentally come to my knowledge, I

shall freely relate. If my account is true, as I have great reason to

believe it is in general, I hope it will warm some virtuous man to stand

up in his place, and call for the papers relating to that negociation.

In a pamphlet, intituled, _The present State of the Nation_, &c. p. 24,

8vo. edit. published last winter, there is this extraordinary passage,

evidently alluding to these papers, which I have often wondered was not

taken notice of; “Whether by the treaty Great Britain obtained all that

she might have obtained, is a question to which those only who were

acquainted with the secrets of the French and Spanish cabinets can give

an answer. _The correspondence relative to that negociation has not been

laid before the public_; for the last parliament approved of the peace

as it was, without thinking it necessary to enquire whether better terms

might not have been had.”

The secret of the negociation, or ultimatum, on the part of England, was

neither in the D. of B. the B. A. at Paris; nor in the late Earl of

Egremont, the _official_ minister at home, who was Secretary of State for

the Southern department; but between Lord Bute and the Sardinian Minister

in London, and the Duc de Choiseul and the Sardinian Minister at Paris.

The fact, of thus committing the management of the most important affairs

of Great Britain to the Ministers of a foreign power, is extraordinary

and alarming, and ought to be considered as highly criminal; especially

when we recollect, that the Sardinian Minister in London, at the time

of his present Majesty’s coronation, signed a protest in favour of the

House of Savoy, which he procured to be legally attested and given in,

in the name of the King his master. He printed, or caused to be printed,

‘the _Genealogie de la Famille Royale d’Angleterre_, by which he hoped,

at a future day, that the ridiculous claims of his master’s family, as

being, although Papists, immediately descended from Henrietta Maria,

the daughter of Charles I. would have prevailed over those of the House

of Brunswick, who are descended from Elizabeth, Electress Palatine, one

degree more remote from the crown, as being the daughter of James I.

He might hope for a general confusion among us; but being born under

arbitrary government, he could not have the least idea of the only

lawful right to the crown of these realms, a parliamentary right. The

contrary doctrine was in Queen Anne’s time expressly declared to be _high

treason_ by a particular statute, the “Act for the better securing her

Majesty’s person and government, and of the succession to the crown of

England in the Protestant line;” ‘_That if any person or persons, from

and after the 25th day of March, 1706, shall maliciously, advisedly and

directly, by writing or printing, declare, maintain, or affirm that the

Kings or Queens of England, with and by the authority of the parliament

of England, are not able to make laws and statutes of sufficient force

and validity to limit and bind the crown of this realm, and the DESCENT,

LIMITATION, INHERITANCE, and government thereof, every such person or

persons shall be guilty of High Treason, and being thereof convicted

and attainted, &c. &c._ Count Viri acted by the express orders of his

Court, in conjunction with the Court of France. In the same manner the

two Courts acted in concert at the beginning of this century, in the

last year of our glorious Deliverer, King William III. Count Maffei, the

Ambassador from Savoy, delivered in the first famous protestation, in the

name of the Duchess of Savoy, against the Hanover succession, at the time

the Duke himself commanded the French army in Italy, with Marshal Catinat

and the Prince of Vaudemont under him, and every action of his life was

dictated by France.’

The present Count V. (who, during his late father’s life time, was known

by the name of M. De Verois) had a pension granted him for his services

in this negociation of 1000l. per ann. on the Irish establishment,

though not in his own name. In the _debates relative to the affairs of

Ireland, in the years 1763 and 1764, &c. inscribed by permission to Lord

Chatham_, we find this fact mentioned, Vol. II. page 475, by Mr. Edmund

Sexton Perry, who thus speaks: “I shall communicate a fact to this House.

There is a pension granted nominally to one George Charles, but really

to Monsieur De Verois, the Sardinian Minister, for negociating the peace

that has just been concluded with the Minister of France. I must confess,

Sir, that, in my opinion, this service deserved no such recompence, at

least on our part. If it is thought a defensible measure, I should be

glad to know, why it was not avowed; and why, if it is proper we should

pay 1000l. a year to Mons. De Verois, we should be made to believe that

we pay it to George Charles.”

Besides the above pension, there was certainly a remittance from France

or Spain, or both, of a considerable sum of money; but for whom it was

designed is not at present so certainly known. However, there is no

doubt that Count V. is thoroughly acquainted with the whole of this

transaction: but now that the affair of the peace begins to be enquired

into, he is preparing to depart the kingdom; and has actually sold his

pension upon the Irish Establishment for 16000l. or thereabouts.

When the D. of B. set out for Paris, which was on the 5th of September,

1762, he had _full powers_ to treat with the French ministry upon the

terms of peace. But when he arrived at Calais, a messenger was dispatched

after him, containing a limitation of those powers. Upon which, he

instantly dispatched the same messenger back to London, declaring (by

letter) he would proceed no further, unless his former instructions were

restored. He waited at Calais for the return of this messenger, who

brought a restoration of his former instructions. However, he submitted,

notwithstanding this affected spirit, to see the conquests of a glorious

war bargained for and surrendered by the two Sardinian ministers. In a

word, the D. made no important figure in the negociation, till an event

turned up, which seemed, by the confusion it occasioned, to be totally

unexpected. This was the capture of the Havannah.

This being only an introductory letter, my next, I hope, will be more

worthy of your attention; at least, it will contain some important

truths. I am, Sir,

Your most humble servant,

An ENGLISHMAN.

LETTER II.

To Dr. MUSGRAVE of PLYMOUTH.

SIR,

My last letter concluded with the mention of the conquest of the

Havannah. The news of this important conquest arrived in England on the

29th of September, 1762, while the treaty of peace was negociating. Until

this period, the D. of B—— had little or no trouble in the negociation,

for the principle articles or great outlines of the terms of peace had

been previously settled between Lord Bute and Mons. De Verois (now Count

Viry) in England, and the Duc de Choiseul and the Sardinian minister at

Paris.

At this time the Right Hon. G—— G—— was Secretary of State for the

Northern department, and by his office (being a commoner) was to carry

the peace through the House of Commons, when it should be laid before

the House. When the news of the conquest of the Havannah came, and it

was directly determined by the Favourite to give up this important

island, because it should not embarrass the negociation, nor impede the

conclusion of the peace, Mr. G——— differed, and, in particular, insisted

upon an indemnification for it, from either France or Spain. He wanted

St. Lucia and Porto Rico, or the entire property of Jucatan and Florida.

The Favourite refused to make application for any of these; upon which

Mr. G——— resigned October 12, 1762[2]. Mr. Fox (now Lord Holland) was

then called upon to carry the peace through the House of Commons. Lord

Halifax succeeded to Mr. G———’s office. But Lord Egremont, being of

Mr. G———’s opinion, prevailed to have an instruction sent to the D. of

B——— to demand Florida only, which was granted without hesitation; for

the messenger who was dispatched to the Duke at Paris with this demand,

returned in eight days, with an account of its having been complied with.

The fact is, the French minister (Choiseul) obliged the Spanish minister

to agree to this demand, without sending to his court. A proof of the

discretionary power which was vested in the French minister by the court

of Spain, to agree to whatever compensation should be insisted upon for

the Havannah.

The following anecdote concerning the English Ultimatum may throw some

light on the preceding fact:—Towards the latter end of the negociation,

Mr. Wood, then Secretary to Lord Egremont, called one day at the Duc

de Nivernois’s (the French Ambassador in London) about three o’clock,

and desired to speak with him. The Swiss told Mr. Wood, his Excellency

was dressing, and could not be disturbed: but Mr. Wood insisting upon