The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Mayas, the Sources of Their History /

Dr. Le Plongeon in Yucatan, His Account o, by Stephen Salisbury, Jr.

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: The Mayas, the Sources of Their History / Dr. Le Plongeon in Yucatan, His Account of Discoveries

Author: Stephen Salisbury, Jr.

Release Date: August 18, 2009 [EBook #29723]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK MAYA, SOURCES OF HISTORY ***

Produced by Julia Miller and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

Transcriber’s Note

Obvious typographical errors have been corrected. A list of changes is

found at the end of the text. Inconsistency in spelling and hyphenation

has been maintained. A list of inconsistently spelled and hyphenated

words is found at the end of the text. The use of accents on foreign

words and the capitalization of titles in foreign languages is not

consistent. This text maintains the original usage. Use of italics on

titles of cited words is not consistent. This text maintains the

original usage.

The following less-common characters are used in this version of the

book. If they do not display correctly, please try changing your font.

† Dagger

‡ Double dagger

Ɔ Capital open O

ŏ Lower-case o with breve

ē Lower-case e with macron

œ oe ligature

[Illustration: Plano de Yucatan 1848]

THE MAYAS,

THE SOURCES OF THEIR HISTORY.

DR. LE PLONGEON IN YUCATAN,

HIS ACCOUNT OF DISCOVERIES.

BY STEPHEN SALISBURY, JR.

FROM PROCEEDINGS OF THE AMERICAN ANTIQUARIAN SOCIETY, OF

APRIL 26, 1876, AND APRIL 25, 1877.

PRIVATELY PRINTED.

WORCESTER:

PRESS OF CHARLES HAMILTON.

1877.

[Inscribed to Mip Sargent,]

_WITH THE RESPECTS OF THE WRITER._

CONTENTS.

THE MAYAS AND THE SOURCES OF THEIR HISTORY, _Page_ 3

DR. LE PLONGEON IN YUCATAN, “ 53

ILLUSTRATIONS.

MAP OF YUCATAN, FRONTISPIECE.

LOCALITY OF DISCOVERIES AT CHICHEN-ITZA, _Page_ 58

STATUE EXHUMED AT CHICHEN-ITZA, “ 62

RELICS FOUND WITH THE STATUE, “ 74

THE MAYAS

AND THE SOURCES OF THEIR HISTORY.

[Proceedings of American Antiquarian Society, April 26, 1876.]

The most comprehensive and accurate map of Yucatan is that which has

been copied for this pamphlet. In the several volumes of travel,

descriptive of Maya ruins, are to be found plans more or less complete,

intended to illustrate special journeys, but they are only partial in

their treatment of this interesting country. The _Plano de Yucatan_,

herewith presented--the work of Sr. Dn. Santiago Nigra de San

Martin--was published in 1848, and has now become extremely rare. It is

valuable to the student, for it designates localities abounding in

ruins--those not yet critically explored, as well as those which have

been more thoroughly investigated--by a peculiar mark, thus [rectangular

box], and it also shows roads and paths used in transportation and

communication. Since its publication political changes have caused the

division of the Peninsula into the States of Yucatan and Campeachy,

which change of boundaries has called for the preparation of a new and

improved map. Such an one is now being engraved at Paris and will soon

be issued in this country. It is the joint production of Sr. Dn. Joaquin

Hubbe and Sr. Dn. Andres Aznar Pérez, revised by Dr. C. Hermann Berendt.

The early history of the central portions of the western hemisphere has

particularly attracted the attention of European archæologists, and

those of France have already formed learned societies engaged

specifically in scientific and antiquarian investigations in Spanish

America. It is to the French that credit for the initiative in this most

interesting field of inquiry is especially due, presenting an example

which can not fail to be productive of good results in animating the

enthusiasm of all engaged in similar studies.

The Société Américaine de France (an association, like our own, having

the study of American Antiquities as a principal object, and likely to

become prominent in this field of inquiry), has already been briefly

mentioned by our Librarian; but the reception of the _Annuaire_ for

1873, and a statement of the present condition of the Society in the

_Journal des Orientalistes_ of February 5, 1876, gives occasion for a

more extended notice. The Society was founded in 1857; and among those

most active in its creation were M. Brasseur de Bourbourg, M. Léon de

Rosny, and M. Alfred Maury. The objects of the association, as

officially set forth, were, first, the publication of the works and

collections of M. Aubin, the learned founder of a theory of American

Archæology, which it was hoped would throw much light upon the

hieroglyphical history of Mexico before the conquest;[4-*] second, the

publication of grammars and dictionaries of the native languages of

America; third, the foundation of professorships of History,

Archæology, and American Languages; and fourth, the creation, outside of

Paris, of four Museums like the Museum of Saint Germain, under the

auspices of such municipalities as encourage their foundation, as

follows:

A.--Musée mexicaine.

B.--Musée péruvienne et de l’Amérique du Sud.

C.--Musée ethnographique de l’Amérique du Nord.

D.--Musée des Antilles.

The list of members contains the names of distinguished archæologists in

Europe, and a foreign membership already numerous; and it is

contemplated to add to this list persons interested in kindred studies

from all parts of the civilized world. The publications of the Society,

and those made under its auspices, comprehend, among others, _Essai sur

le déchiffrement de l’Ecriture hiératique de l’Amérique Centrale_, by M.

Léon de Rosny, President of the Society, 1 vol. in folio, with numerous

plates: This work treats critically the much controverted question of

the signification of Maya characters, and furnishes a key for their

interpretation.[5-*] Also, _Chronologie hiéroglyphico phonétique des

Rois Aztéques de 1352 à 1522, retrouvée dans diverses mappes américaines

antiques, expliquée et précédée d’une introduction sur l’Écriture

mexicaine_, by M. Edouard Madier de Montjau. The archæology of the two

Americas, and the ethnography of their native tribes, their languages,

manuscripts, ruins, tombs and monuments, fall within the scope of the

Society, which it is their aim to make the school and common centre of

all students of American pre-Columbian history. M. Émile Burnouf, an

eminent archæologist, is the Secretary. The _Archives_ for 1875 contain

an article on the philology of the Mexican languages, by M. Aubin; an

account of a recent voyage to the regions the least known of Mexico and

Arizona, by M. Ch. Schoebel; the last written communication of M. de

Waldeck, the senior among travellers; an article by M. Brasseur de

Bourbourg, upon the language of the Wabi of Tehuantepec; and an essay by

M. de Montjau, entitled _Sur quelques manuscripts figuratifs mexicains_,

in which the translation of one of these manuscripts, by M. Ramirez of

Mexico, is examined critically, and a different version is offered. The

author arrives at the startling conclusion, that we have thus far taken

for veritable Mexican manuscripts, many which were written by the

Spaniards, or by their order, and which do not express the sentiments of

the Indians. Members of this Society, also, took an active part in the

deliberations of the _Congrès international des Américanistes_, which

was held at Nancy in 1875.

It was a maxim of the late Emperor Napoléon III., that France could go

to war for an idea. The Spanish as discoverers were actuated by the love

of gold, and the desire of extending the knowledge and influence of

christianity, prominently by promoting the temporal and spiritual power

of the mother church. In their minds the cross and the flag of Spain

were inseparably connected. The French, however, claim to be ready to

explore, investigate and study, for science and the discovery of truth

alone. In addition to the _Commission Scientifique du Mexique_ of 1862,

which was undertaken under the auspices of the French government, and

which failed to accomplish all that was hoped, the Emperor Maximilian I.

of Mexico projected a scientific exploration of the ruins of Yucatan

during his brief reign, while he was sustained by the assistance of the

French. The tragic death of this monarch prevented the execution of his

plans; but his character, and his efforts for the improvement of Mexico,

earned for this accomplished but unfortunate prince the gratitude and

respect of students of antiquity, and even of Mexicans who were

politically opposed to him.[7-*]

The attention of scholars and students of American Antiquities is

particularly turned to Central America, because in that country ruins of

a former civilization, and phonetic and figurative inscriptions, still

exist and await an interpretation. In Central America are to be found a

great variety of ruins of a higher order of architecture than any

existing in America north of the Equator. Humboldt speaks of these

remains in the following language: “The architectural remains found in

the peninsula of Yucatan testify more than those of Palenque to an

astonishing degree of civilization. They are situated between Valladolid

Mérida and Campeachy.”[7-†] Prescott says of this region, “If the

remains on the Mexican soil are so scanty, they multiply as we descend

the southeastern slope of the Cordilleras, traverse the rich valleys of

Oaxaca, and penetrate the forests of Chiapas and Yucatan. In the midst

of these lonely regions, we meet with the ruins recently discovered of

several eastern cities--Mitla, Palenque, and Itzalana or Uxmal,--which

argue a higher civilization than anything yet found on the American

Continent.”[8-*]

The earliest account in detail--as far as we know--of Mayan ruins,

situated in the States of Chiapas and Yucatan, is presented in the

narrative of Captain Antonio del Rio, in 1787, entitled _Description of

an ancient city near Palenque_. His investigation was undertaken by

order of the authorities of Guatemala, and the publication in Europe of

its results was made in 1822. In the course of his account he says, “a

Franciscan, Thomas de Soza, of Mérida, happening to be at Palenque, June

21, 1787, states that twenty leagues from the city of Mérida, southward,

between Muna, Ticul and Noxcacab, are the remains of some stone

edifices. One of them, very large, has withstood the ravages of time,

and still exists in good preservation. The natives give it the name of

Oxmutal. It stands on an eminence twenty yards in height, and measures

two hundred yards on each façade. The apartments, the exterior corridor,

the pillars with figures in medio relievo, decorated with serpents and

lizards, and formed with stucco, besides which are statues of men with

palms in their hands, in the act of beating drums and dancing, resemble

in every respect those observable at Palenque.”[8-†] After speaking of

the existence of many other ruins in Yucatan, he says he does not

consider a description necessary, because the identity of the ancient

inhabitants of Yucatan and Palenque is proved, in his opinion, by the

strange resemblance of their customs, buildings, and acquaintance with

the arts, whereof such vestiges are discernible in those monuments which

the current of time has not yet swept away.

The ruins of Yucatan, those of the state of Chiapas and of the Island of

Cozumel, are very splendid remains, and they are all of them situated in

a region where the Maya language is still spoken, substantially as at

the time of the Spanish discovery.[9-*]

Don Manuel Orosco y Berra, says of the Indian inhabitants, “their

revengeful and tenacious character makes of the Mayas an exceptional

people. In the other parts of Mexico the conquerors have imposed their

language upon the conquered, and obliged them gradually to forget their

native language. In Yucatan, on the contrary, they have preserved their

language with such tenacity, that they have succeeded to a certain point

in making their conquerors accept it. Pretending to be ignorant of the

Spanish, although they comprehend it, they never speak but in the Maya

language, obeying only orders made in that language, so that it is

really the dominant language of the peninsula, with the only exception

of a part of the district of Campeachy.”[9-†]

In Cogolludo’s Historia de Yucatan, the similarity of ruins throughout

this territory is thus alluded to: “The incontestable analogy which

exists between the edifices of Palenque and the ruins of Yucatan places

the latter under the same origin, although the visible progress of art

which is apparent assigns different epochs for their construction.”[10-*]

So we have numerous authorities for the opinion, that the ruins in Chiapas

and Yucatan were built by the same or by a kindred people, though at

different periods of time, and that the language which prevails among the

Indian population of that region at the present day, is the same which was

used by their ancestors at the time of the conquest.

Captain Dupaix, who visited Yucatan in 1805, wrote a description of the

ruins existing there, which was published in 1834; but it was reserved

for M. Frédéric de Waldeck to call the attention of the European world

to the magnificent remains of the Maya country, in his _Voyage

pittoresque et archaeologique dans la province de Yucatan, pendant des

années 1834-1836_, Folio, with plates, Paris, 1838. This learned

centenarian became a member of the Antiquarian Society in 1839, and his

death was noticed at the last meeting. Following him came the celebrated

Eastern traveller, John L. Stephens, whose interesting account of his

two visits to that country in 1840 and 1841, entitled _Incidents of

travel in Central America, Chiapas and Yucatan_, in two volumes, and

Incidents of travel in Yucatan, in two volumes, is too familiar to

require particular notice at this point. It may not be uninteresting to

record the fact, that Mr. Stephens’ voyages and explorations in Yucatan

were made after the suggestion and with the advice of Hon. John R.

Bartlett, of Providence, R. I., a member of this Society, who obtained

for this traveller the copy of Waldeck’s work which he used in his

journeyings. Désiré Charnay, a French traveller, published in 1863 an

account entitled _Cités et Ruines Américaines_, accompanied by a

valuable folio Atlas of plates.

The writer of this report passed the winter of 1861 at Mérida, the

capital of the Province of Yucatan, as the guest of Don David Casares,

his classmate, and was received into his father’s family with a kindness

and an attentive hospitality which only those who know the warmth and

sincerity of tropical courtesy can appreciate.[11-*] The father, Don

Manuel Casares, was a native of Spain, who had resided in Cuba and in

the United States. He was a gentleman of the old school, who, in the

first part of his life in Yucatan, had devoted himself to teaching, as

principal of a high school in the city of Mérida, but was then occupied

in the management of a large plantation, upon which he resided most of

the year, though his family lived in the city. He was possessed of

great energy and much general information, and could speak English with

ease and correctness. Being highly respected in the community, he was a

man of weight and influence, the more in that he kept aloof from all

political cabals, in which respect his conduct was quite exceptional.

The Abbé Brasseur de Bourbourg, in his _Histoire des nations civilizées

du Mexique_, acknowledges the valuable assistance furnished him by Señor

Casares, whom he describes as a learned Yucateco and ancient deputy to

Mexico.[12-*]

Perhaps some of the impressions received, during a five months’ visit,

will be pardoned if introduced in this report. Yucatan is a province of

Mexico, very isolated and but little known. It is isolated, from its

geographical position, surrounded as it is on three sides by the waters

of the Gulf of Mexico and the Atlantic Ocean; and it is but little

known, because its commerce is insignificant, and its communication with

other countries, and even with Mexico, is infrequent. It has few ports.

Approach to the coast can only be accomplished in lighters or small

boats; while ships are obliged to lie off at anchor, on account of the

shallowness of the water covering the banks of sand, which stretch in

broad belts around the peninsula. The country is of a limestone

formation, and is only slightly elevated above the sea. Its general

character is level, but in certain districts there are table lands; and

a mountain range runs north-easterly to the town of Maxcanu, and thence

extends south-westerly to near the centre of the State. The soil is

generally of but little depth, but is exceedingly fertile.

There are no rivers in the northern part of the province, and only the

rivers Champoton, and the Uzumacinta with its branches, in the

south-western portion; but there are several small lakes in the centre

of Yucatan, and a large number of artificial ponds in the central and

southern districts. The scarcity of water is the one great natural

difficulty to be surmounted in most parts of the country; but a supply

can commonly be obtained by digging wells, though often at so great a

depth that the cost is formidable. The result is that the number of

wells is small, and in the cities of Mérida and Campeachy rain water is

frequently stored in large cisterns for domestic purposes. From the

existence of cenotes or ponds with an inexhaustible supply of water at

the bottom of caves, and because water can be reached by digging and

blasting, though with great effort and expense, the theory prevails in

Yucatan that their territory lies above a great underground lake, which

offers a source of supply in those sections where lakes, rivers and

springs, are entirely unknown.

A very healthful tropical climate prevails, and the year is divided into

the wet and the dry season, the former beginning in June and lasting

until October, the latter covering the remaining portions of the year.

During the dry season of 1861-2, the thermometer ranged from 75° to 78°

in December and January, and from 78° to 82° in February, March and

April. Early in the dry season vegetation is luxuriant, the crops are

ripening, and the country is covered with verdure; but as the season

progresses the continued drouth, which is almost uninterrupted, produces

the same effect upon the external aspect of the fields and woods as a

northern winter. Most of the trees lose their leaves, the herbage dries

up, and the roads become covered with a thick dust. During

exceptionally dry seasons thousands of cattle perish from the entire

lack of subsistence, first having exhausted the herbage and then the

leaves and shrubbery.

The population of the peninsula is now about 502,731, four-fifths of

which are Indians and Mestizos or half-breeds. The general business of

the country is agricultural, and the territory is divided into landed

estates or farms, called haciendas, which are devoted to the breeding of

cattle, and to raising jenniken or Sisal hemp, and corn. Cotton and

sugar are also products, but not to an extent to admit of exportation.

Some of the plantations are very large, covering an area of six or seven

miles square, and employing hundreds of Indians as laborers.

Farm houses upon the larger estates are built of stone and lime, covered

with cement, and generally occupy a central position, with private roads

diverging from them. These houses, which are often very imposing and

palatial, are intended only for the residence of the owners of the

estate and their major-domos or superintendents. The huts for the Indian

laborers are in close proximity to the residence of the proprietor, upon

the roads which lead to it, and are generally constructed in an oval

form with upright poles, held together by withes of bark; and they are

covered inside and out with a coating of clay. The roofs are pointed,

and also made with poles, and thatched with straw. They have no

chimneys, and the smoke finds its way out from various openings

purposely left. The huts have no flooring, are larger than the common

wigwams of the northern Indians, and ordinarily contain but a single

room. The cattle yards of the estate, called corrals, immediately join

the residence of the proprietor, and are supplied with water by

artificial pumping. All the horses and cattle are branded, and roam at

will over the estates, (which are not fenced, except for the protection

of special crops), and resort daily to the yards to obtain water. This

keeps the herds together. The Indian laborers are also obliged to rely

entirely upon the common well of the estate for their supply of water.

The Indians of Yucatan are subject to a system of péonage, differing but

little from slavery. The proprietor of an estate gives each family a

hut, and a small portion of land to cultivate for its own use, and the

right to draw water from the common well, and in return requires the

labor of the male Indians one day in each week under superintendence. An

account is kept with each Indian, in which all extra labor is credited,

and he is charged for supplies furnished. Thus the Indian becomes

indebted to his employer, and is held upon the estate by that bond.

While perfectly free to leave his master if he can pay this debt, he

rarely succeeds in obtaining a release. No right of corporal punishment

is allowed by law, but whipping is practiced upon most of the estates.

The highways throughout the country are numerous, but generally are

rough, and there is but little regular communication between the various

towns. From the cities of Mérida and Campeachy, public conveyances leave

at stated times for some of the more important towns; but travellers to

other points are obliged to depend on private transportation. A railroad

from Mérida to the port of Progreso, a distance of sixteen miles, was in

process of being built, but the writer is not aware of its completion.

The peninsula is now divided into the States of Yucatan, with a

population of 282,634, with Mérida for a capital, and Campeachy, with a

population of 80,366, which has the city of Campeachy as its capital.

The government is similar to our state governments, but is liable to be

controlled by military interference. The States are dependent upon the

central government at Mexico, and send deputies to represent them in the

congress of the Republic. In the south-western part of the country there

is a district very little known, which is inhabited by Indians who have

escaped from the control of the whites and are called Sublevados. These

revolted Indians, whose number is estimated at 139,731, carry on a

barbarous war, and make an annual invasion into the frontier towns,

killing the whites and such Indians as will not join their fortunes.

With this exception, the safety of life and property is amply protected,

and seems to be secured, not so much by the severity of the laws, as by

the peaceful character of the inhabitants of all races. The trade of the

country, except local traffic, is carried on by water. Regular steam

communication occurs monthly between New York and Progreso, the port of

Mérida, via Havana, and occasionally barques freighted with corn, hides,

hemp and other products of the country, and also carrying a small number

of passengers, leave its ports for Havana, Vera Cruz and the United

States. Freight and passengers along the coast are transported in flat

bottomed canoes. Occasional consignments of freight and merchandise

arrive by ship from France, Spain and other distant ports.

The cities of Mérida and Campeachy are much like Havana in general

appearance. The former has a population of 23,500, is the residence of

the Governor, and contains the public buildings of the State, the

cathedral--an imposing edifice,--the Bishop’s palace, an ecclesiastical

college, fifteen churches, a hospital, jail and theatre. The streets are

wide and are laid out at right angles. The houses, which are generally

of one story, are large, and built of stone laid in mortar or cement;

and they are constructed in the Moorish style, with interior court yards

surrounded with corridors, upon which the various apartments open. The

windows are destitute of glass, but have strong wooden shutters; and

those upon the public streets often project like bow windows, and are

protected by heavy iron gratings. The inhabitants are exceedingly

hospitable, and there is much cultivated society in both Mérida and

Campeachy. As the business of the country is chiefly agricultural, many

of the residents in the cities own haciendas in the country, where they

entertain large parties of friends at the celebration of a religious

festival on their plantations, or in the immediate neighborhood. The

people are much given to amusements, and the serious duties of life are

often obliged to yield to the enjoyments of the hour. The Catholic

religion prevails exclusively, and has a very strong hold upon the

population, both white and Indian, and the religious services of the

church are performed with great ceremony, business of all kinds being

suspended during their observance.

The aboriginal ruins, to which so much attention has been directed, are

scattered in groups through the whole peninsula. Mérida is built upon

the location of the ancient town Tihoo, and the materials of the Indian

town were used in its construction. Sculptured stones, which formed the

ornamental finish of Indian buildings, are to be seen in the walls of

the modern houses.[18-*] An artificial hill, called “El Castillo,” was

formerly the site of an Indian temple, and is curious as the only mound

remaining of all those existing at the time of the foundation of the

Spanish city. This mound is almost the only trace of Indian workmanship,

in that immediate locality, which has not been removed or utilized in

later constructions.[18-†] It appears that a large part of the

building material throughout the province was taken from aboriginal

edifices, and the great number of stone churches of considerable size,

which have been built in all the small towns in that country, is proof

of the abundance of this material.

The ruins of Uxmal, said to be the most numerous and imposing of any in

the province, were visited by the writer in company with a party of

sixteen gentlemen from Mérida, of whom two only had seen them before.

The expedition was arranged out of courtesy to the visitor, and was

performed on horseback. The direct distance was not more than sixty

miles in a southerly direction, but the excursion was so managed as to

occupy more than a week, during which time the hospitality of the

haciendas along the route was depended upon for shelter and

entertainment. Some of the plantations visited were of great extent, and

among others, that called Guayalké was especially noticeable for its

size, and also for the beauty and elegance of the farm house of the

estate, which was constructed entirely of stone, and was truly palatial

in its proportions. This building is fully described by Mr.

Stephens.[19-*] The works of this writer form an excellent hand-book for

the traveller. His descriptions are truthful, and the drawings by Mr.

Catherwood are accurate, and convey a correct idea of the general

appearance of ruins, and of points of interest which were visited; and

the personal narrative offers a great variety of information, which

could only be gathered by a traveller of much experience in the study of

antiquities. Such at least is the opinion of the people of that country.

His works are there quoted as high authority respecting localities which

he visited and described; and modern Mexican philologists and

antiquaries refer to Stephens’ works and illustrations with confidence

in his representations, and with respect and deference for his opinions

and inferences.[19-†]

At various points along the route, portions of ruined edifices were seen

but not explored. The ruins of Uxmal are distant about a mile from the

hacienda buildings, and extend as far as the eye can reach. They belong

to Don Simon Peon, a gentleman who, though he does not reside there, has

so much regard for their preservation that he will not allow the ruins

to be removed or interfered with for the improvement of the estate, in

which respect he is an exception to many of the planters. Here it may be

remarked, that the inhabitants generally show little interest in the

antiquities of their country, and no public effort is made to preserve

them. The ruins which yet remain undisturbed have escaped destruction,

in most instances, only because their materials have not been required

in constructing modern buildings. Much of the country is thinly

inhabited, and parts of it are heavily wooded. It is there that the

remains of a prior civilization have best escaped the hand of man, more

to be dreaded than the ravages of time.

The stone edifices of Uxmal are numerous, and are generally placed upon

artificial elevations; they are not crowded together, but are scattered

about singly and in groups over a large extent of territory. The most

conspicuous is an artificial pyramidal mound, upon the top of which is a

stone building two stories in height, supposed to have been used as a

sacrificial temple. One side of this mound is perpendicular; the

opposite side is approached by a flight of stone steps. The building on

the top, and the steps by which the ascent is made are in good

preservation. Some of the large buildings are of magnificent

proportions, and are much decorated with bas reliefs of human figures

and faces in stone, and with other stone ornaments. The writer does not

recollect seeing any stucco ornamentation at this place, though such

material is used elsewhere. What are popularly called “House of the

Governor” and “House of the Nuns,” are especially remarkable for their

wonderful preservation; so that from a little distance they appear

perfect and entire, except at one or two points which look as if struck

by artillery. The rooms in the ruins are of various sizes, and many of

them could be made habitable with little labor, on removing the rubbish

which has found its way into them.

The impression received from an inspection of the ruins of Uxmal was,

that they had been used as public buildings, and residences of officers,

priests and high dignitaries. Both Stephens and Prescott are of the

opinion that some of the ruins in this territory were built and occupied

by the direct ancestors of the Indians, who now remain as slaves upon

the soil where once they ruled as lords.[21-*] The antiquity of other

remains evidently goes back to an earlier epoch, and antedates the

arrival of the Spaniards. If the Indians of the time of the conquest

occupied huts like those of the Indians of to-day, it is not strange

that all vestiges of their dwellings should have disappeared. Mr.

Stephens gives an interesting notice of the first formal conveyance of

the property of Uxmal, made by the Spanish government in 1673, which was

shown him by the present owner, in which the fact that the Indians,

then, worshipped idols in some of the existing edifices on that estate,

is mentioned. Another legal instrument, in 1688, describes the livery of

seizin in the following words, “In virtue of the power and authority by

which the same title is given to me by the said governor, and complying

with its terms, I took by the hands the said Lorenzo de Evia, and he

walked with me all over Uxmal and its buildings, opened and shut some

doors that had several rooms (connected), cut within the space several

trees, picked up fallen stones and threw them down, drew water from one

of the aguadas (artificial ponds) of the said place of Uxmal, and

performed other acts of possession.”[21-†] These facts are interesting

as indicating actual or recent occupation; and a careful investigation

of documents relating to the various estates, of which the greater part

are said to be written in the Maya language, might throw light upon the

history of particular localities.

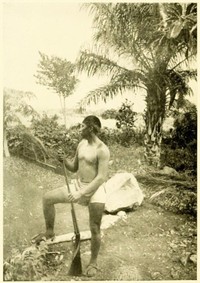

The Maya Indians are shorter and stouter, and have a more delicate

exterior than the North American Savages. Their hands and feet are

small, and the outlines of their figures are graceful. They are capable

of enduring great fatigue, and the privation of food and drink, and bear

exposure to the tropical sun for hours with no covering for the head,

without being in the least affected. Their bearing evinces entire

subjection and abasement, and they shun and distrust the whites. They do

not manifest the cheerfulness of the negro slave, but maintain an

expression of indifference, and are destitute of all curiosity or

ambition. These peculiarities are doubtless the results of the treatment

they have received for generations. The half-breeds, or Mestizos, prefer

to associate with the whites rather than with the Indians; and as a rule

all the domestic service throughout the country is performed by that

class. Mestizos often hold the position of major-domos, or

superintendents of estates, but Indians of pure blood are seldom

employed in any position of trust or confidence. They are punctilious in

their observance of the forms and ceremonies of the Catholic religion,

and a numerous priesthood is maintained largely by the contributions of

this race. The control exercised by the clergy is very powerful, and

their assistance is always sought by the whites in cases of controversy.

The Indians are indolent and fond of spectacles, and the church offers

them an opportunity of celebrating many feast days, of which they do not

fail to avail themselves.

When visiting the large estate of Chactun, belonging to Don José

Dominguez, thirty miles south-west of Mérida, at a sugar rancho called

Orkintok, the writer saw a large ruin similar to that called the “House

of the Nuns” at Uxmal. It was a building of a quadrangular shape, with

apartments opening on an interior court in the centre of the quadrangle.

The building was in good preservation, and some of the rooms were used

as depositories for corn. The visiting party breakfasted in one of the

larger apartments. From this hacienda an excursion was made to Maxcanu,

to visit an artificial mound, which had a passage into the interior,

with an arched stone ceiling and retaining walls.[23-*] This passage was

upon a level with the base of the mound, and branched at right angles

into other passages for hundreds of feet. Nothing appeared in these

passages to indicate their purpose. The labyrinth was visited by the

light of candles and torches, and the precaution of using a line of

cords was taken to secure a certainty of egress. A thorough exploration

was prevented by the obstructions of the _débris_ of the fallen roof.

Other artificial mounds encountered elsewhere had depressions upon the

top, doubtless caused by the falling in of interior passages or

apartments. There is no account of the excavation of Yucatan mounds for

historical purposes, though Cogolludo says there were other mounds

existing at Mérida in 1542, besides “El grande de los Kues,” which,

certainly, have now disappeared; but no account of their construction

has come down to us.[23-†] The same author also says, that, with the

stone constructions of the Indian city churches and houses were built,

besides the convent and church of the Mejorada, and also the church of

the Franciscans, and that there was still more material left for others

which they desired to build.[24-*] It is then, certainly, a plausible

supposition that the great mounds were many of them constructed with

passages like that at Orkintok, and that they have furnished from their

interiors worked and squared stones, which were used in the construction

of the modern city of Mérida by the Spanish conquerors.

When the Spanish first invaded Mexico and Yucatan they brought with them

a small number of horses, which animals were entirely unknown to the

natives, and were made useful not only as cavalry but also in creating a

superstitious reverence for the conquerors, since the Indians at first

regarded the horse as endowed with divine attributes. Cortez in his

expedition from the city of Mexico to Honduras in 1524, passed through

the State of Chiapas near the ruins called Palenque,--of which ancient

city, however, no mention is made in the accounts of that

expedition,--and rested at an Indian town situated upon an island in

Lake Peten in Guatemala. This island was then the property of an

emigrant tribe of Maya Indians; and Bernal Diaz, the historian of the

expedition, says, that “its houses and lofty teocallis glistened in the

sun, so that it might be seen for a distance of two leagues.” According

to Prescott, “Cortez on his departure left among this friendly people

one of his horses, which had been disabled by an injury in the foot. The

Indians felt a reverence for the animal, as in some way connected with

the mysterious power of the white men. When their visitors had gone they

offered flowers to the horse, and as it is said, prepared for him many

savory messes of poultry, such as they would have administered to their

own sick. Under this extraordinary diet the poor animal pined away and

died. The affrighted Indians raised his effigy in stone, and placing it

upon one of their teocallis, did homage to it as to a deity.”[25-*] At

the hacienda of Don Manuel Casares called Xuyum, fifteen miles

north-east from Mérida, a number of cerros, or mounds, and the ruins of

several small stone structures built on artificial elevations, were

pointed out to the writer; and his attention was called to two

sculptured heads of horses which lay upon the ground in the neighborhood

of some ruined buildings. They were of the size of life, and

represented, cut from solid limestone, the heads and necks of horses

with the mane clipped, so that it stood up from the ridge of their necks

like the mane of the zebra. The workmanship of the figures was artistic,

and the inference made at the time was, that these figures had served as

bas reliefs on ruins in that vicinity. On mentioning the fact of the

existence of these figures to Dr. Carl Hermann Berendt, who was about to

revisit Yucatan, in 1869, he manifested much interest in regard to them,

and expressed his intention to visit this plantation when he should be

in Mérida. But later inquiries have failed to discover any further trace

of these figures. Dr. Berendt had never seen any representation of

horses upon ruins in Central America, and considered the existence of

the sculptures the more noteworthy, from the fact that horses were

unknown to the natives till the time of the Spanish discovery. The

writer supposes that these figures were sculptured by Indians after the

conquest, and that they were used as decorations upon buildings erected

at the same time and by the same hands.

At the town of Izamal, and also at Zilam, the writer saw gigantic

artificial mounds, with stone steps leading up to a broad level space on

the top. There are no remains of structures on these elevations, but it

seems probable that the space was once occupied by buildings. At Izamal,

which was traditionally the sacred city of the Mayas, a human face in

stucco is still attached to the perpendicular side of one of the smaller

cerros or mounds. The face is of gigantic size, and can be seen from a

long distance. It may have been a representation of Zamna, the founder

of Mayan civilization in Yucatan, to whose worship that city was

especially dedicated.

From this slight glance at the remains in the Mayan territory we are led

to say a few words about their history. In the absence of all authentic

accounts, the traditions of the Mayas, and the writings of Spanish

chroniclers and ecclesiastics, offer the only material for our object.

M. L’Abbé Brasseur de Bourbourg, the learned French traveller and

Archæologist, in his _Histoire des Nations Civilisées du Mexique et de

l’Amérique Centrale durant les siècles antérieurs à Christophe Columb_,

has given a very voluminous and interesting account of Mayan history

prior to the arrival of Europeans. It was collected by a careful study

of Spanish and Mayan manuscripts, and will serve at least to open the

way for further investigation to those who do not agree with its

inferences and conclusions. The well known industry and enthusiasm of

this scholar have contributed very largely to encourage the study of

American Archæology in Europe, and his name has been most prominently

associated with the later efforts of the French in the scientific study

of Mexican antiquities. A brief notice of some of the marked epochs of

Mayan history, as he presents them, will not perhaps be out of place in

this connection.

Modern investigations, in accord with the most ancient traditions, make

Tobasco and the mouths of the Tobasco river, and the Uzumacinta, the

first cradle of civilization in Central America. At the epoch of the

Spanish invasion, these regions, and the interior provinces which

bordered on them, were inhabited by a great number of Indian tribes.

There was a time when the major part of the population of that region

spoke a common language, and this language was either the Tzendale,

spoken to-day by a great number of the Indians in the State of Chiapas,

or more likely the Maya, the only language of the peninsula of Yucatan.

When the Spaniards first appeared, the native population already

occupied the peninsula, and a great part of the interior region of that

portion of the continent. Learned Indians have stated, that they heard

traditionally from their ancestors, that at first the country was

peopled by a race which came from the east, and that their God had

delivered them from the pursuit of certain others, in opening to them a

way of escape by means of the sea. According to tradition, Votan, a

priestly ruler, came to Yucatan many centuries before the Christian era,

and established his first residence at Nachan, now popularly called

Palenque. The astonishment of the natives at the coming of Votan was as

great as the sensation produced later at the appearance of the

Spaniards. Among the cities which recognized Votan as founder, Mayapan

occupied a foremost rank and became the capital of the Yucatan

peninsula; a title which it lost and recovered at various times, and

kept until very near to the date of the arrival of the Spaniards. The

ruins of Mayapan are situated in the centre of the province, about

twenty-four miles from those of Uxmal. Mayapan, Tulha--situated upon a

branch of the Tobasco river,--and Palenque, are considered the most

ancient cities of Central America.

Zamna however was revered by the Mayas as their greatest lawgiver, and

as the most active organizer of their powerful kingdom. He was a ruler

of the same race as Votan, and his arrival took place a few years after

the building of Palenque. The first enclosure of Mayapan surrounded only

the official and sacred buildings, but later this city was much

extended, so that it became one of the largest of ancient America. Zamna

is said to have reigned many years, and to have introduced arts and

sciences which enriched his kingdom. He was buried at Izamal, which

became a shrine where multitudes of pilgrims rendered homage to this

benefactor of their country. Here was established an oracle, famous

throughout that whole region, which was also resorted to for the cure of

diseases.

Mayan chronology fixes the year 258 of the Christian era as the date

when the Tutul-Xius, a princely family from Tulha, left Guatemala and

appeared in Yucatan. They conciliated the good will of the king of

Mayapan and rendered themselves vassals of the crown of Maya. The

Tutul-Xius founded Mani and also Tihoo, afterwards the modern city of

Mérida. The divinity most worshipped at Tihoo was Baklum-Chaam, the

Priapus of the Mayas, and the great temple erected as a sanctuary to

this god was but little inferior to the temple of Izamal. It bore the

title “_Yahan-Kuna_,” most beautiful temple. A letter from Father

Bienvenida to Philip II., speaks of this city in these terms, “The city

is 30 leagues in the interior, and is called Mérida, which name it

takes on account of the beautiful buildings which it contains, because

in the whole extent of country which has been discovered, not one so

beautiful has been met with. The buildings are finely constructed of

hammered stone, laid without cement, and are 30 feet in height. On the

summit of these edifices are four apartments, divided into cells like

those of the monks, which are twenty feet long and ten feet wide. The

posts of the doors are of a single stone, and the roof is vaulted. The

priests have established a convent of St. Francis in the part which has

been discovered. It is proper that what has served for the worship of

the demon should be transformed into a temple for the service of

God.”[29-*]

Later in history a prince named Cukulcan arrived from the west and

established himself at Chichen-Itza. Owing to quarrels in the Mayan

territory, he was asked to take the supreme government of the empire,

with Mayapan as the capital city. By his management the government was

divided into three absolute sovereignties, which upon occasion might act

together and form one. The seven succeeding sovereigns of Mayapan

embellished and improved the country, and it was very prosperous. At

this time the city of Uxmal, governed by one of the Tutul-Xius, began to

rival the city of Mayapan in extent of territory and in the number of

its vassals. The towns of Noxcacab, Kabah, Bocal and Nŏhpat were

among its dependencies.

The date of the foundation of Uxmal has been fixed at A. D. 864. At this

epoch, great avenues paved with stone, were constructed, the most

remarkable of which appeared to have been that which extends from the

interior to the shores of the sea opposite Cozumel, upon the North-East

coast, and the highway which led to Izamal constructed for the

convenience of pilgrims. A long peace then reigned between the princes

of the several principal cities, which was brought to an end by an

alliance formed against the King of Mayapan. The rulers of Chichen and

Uxmal dared openly to condemn the conduct of the king of Mayapan,

because he had employed hirelings to protect himself against his own

people, who were provoked by his tyrannical exactions, and had

transferred his residence to Kimpech, upon which town and neighborhood,

alone, he bestowed his royal favors. His people were especially outraged

by the introduction of slavery, which had been hitherto unknown to them.

A change of rulers at Mayapan failed to allay the troubles in the

empire, and by a conspiracy of the independent princes, the new tyrant

of Mayapan was deposed, and he was defeated in a three days battle at

the city of Mayapan. The palace was taken, and the king and his family

were brutally murdered. The city was then given to the flames and was

left a vast and desolate heap of ruins.

Then one of the Tutul-Xius, prince of Uxmal, on his return, was crowned

and received the title of supreme monarch of the Mayas. This king

governed the country with great wisdom, extending his protection over

the foreign mercenaries of the former tyrant, and offering them an

asylum not far from Uxmal, where are now the remains of the towns

Pockboc, Sakbache and Lebna. It is believed that the city of Mayapan was

then rebuilt, and existed shorn of some of its former greatness, but

later it was again the cause of dissension in the kingdom, and was again

destroyed. This event is said to have occurred in A. D. 1464. Peace then

reigned in Yucatan for more than twenty years, and there was a period of

great abundance and prosperity. At the end of this time the country was

subjected to a series of disasters. Hurricanes occurred, doing

incalculable damage; plagues followed with great destruction of life;

and thus began the depopulation of the peninsula. Then the Spaniards

arrived, and the existence of Indian power in Yucatan came to an end.

The foregoing is necessarily an abridged, hastily written, and very

imperfect sketch of some of the more prominent facts connected with the

supposed early history of Mayan civilization, which have been brought

together with care, labor, and great elaboration, by the Abbé Brasseur

de Bourbourg. Much of this history is accepted as correct from the

weight of the authorities which support and corroborate it, but the

whole subject is still an open one in the opinion of scholars and

archæologists.

The learned Abbé is now no more, but the record of his labors exists in

his published works, and in the impulse which he gave to archæological

investigations. We receive the first notice of his death from Mr. Hubert

Howe Bancroft, who pays the following eloquent tribute to his memory:

“Brasseur de Bourbourg devoted his life to the study of American

primitive history. In actual knowledge pertaining to his chosen

subjects, no man ever equalled or approached him. Besides being an

indefatigable student, he was an elegant writer. In the last decade of

his life, he conceived a new and complicated theory respecting the

origin of the American people, or rather the origin of Europeans and

Asiatics from America, made known to the world in his ‘_Quatre

Lettres_.’ His attempted translation of the manuscript _Troano_ was made

in support of this theory. By reason of the extraordinary nature of the

views expressed, and the author’s well-known tendency to build

magnificent structures on a slight foundation, his later writings were

received, for the most part by critics utterly incompetent to understand

them, with a sneer, or what seems to have grieved the writer more, in

silence. Now that the great Americanist is dead, while it is not likely

that his theories will ever be received, his zeal in the cause of

antiquarian science, and the many valuable works from his pen will be

better appreciated. It will be long ere another shall undertake, with

equal devotion and ability, the well nigh hopeless task.”[32-*]

Among the historical records relating to the aborigines of Spanish

America, there is none more valuable than the manuscript of Diego de

Landa--Second Bishop of Yucatan, in 1573,--which was discovered and

published by M. de Bourbourg. It contains an account of the manners and

customs of the Maya Indians, a description of some of their chief towns;

and more important than all besides, it furnishes an alphabet, which is

the most probable key that is known to us for reading the hieroglyphics

which are found upon many of the Yucatan ruins. The alphabet, though

imperfect in itself, may at some future time explain, not only the

inscriptions, but also the manuscripts of this ancient period. Although

an attempt of its discoverer, to make use of the alphabet for

interpreting the characters of the manuscript _Troano_, has failed to

satisfy scholars, its study still engages the attention of other learned

archæologists and antiquaries.

Bishop Landa gives the following description of Mayan manuscripts or

books: “They wrote their books on a large, highly decorated leaf,

doubled in folds and enclosed between two boards, and they wrote on both

sides in columns corresponding to the folds. The paper they made of the

roots of a tree, and gave it a white varnish on which one could write

well. This art was known by certain men of high rank, and because of

their knowledge of it they were much esteemed, but they did not practice

the art in public. This people also used certain characters or letters,

with which they wrote in their books of their antiquities and their

sciences: and by means of these, and of figures, and by certain signs in

their figures, they understood their writings, and made them understood,

and taught them. We found among them a great number of books of these

letters of theirs, and because they contained nothing which had not

superstitions and falsities of the devil, we burned them all; at which

they were exceedingly sorrowful and troubled.”[33-*]

In Cogolludo’s Historia de Yucatan, there is an account of a destruction

of Indian antiquities by Bishop Landa, called an auto-dä-fē, of which

we give a translation: “This Bishop, who has passed for an illustrious

saint among the priests of this province, was still an extravagant

fanatic, and so hard hearted that he became cruel. One of the heaviest

accusations against him, which his apologists could not deny or justify,

was the famous auto-dä-fē, in which he proceeded in a most arbitrary

and despotic manner. Father Landa destroyed many precious memorials,

which to-day might throw a brilliant light over our ancient history,

still enveloped in an almost impenetrable chaos until the period of the

conquest. Landa saw in books that he could not comprehend, cabalistic

signs, and invocations to the devil. From notes in a letter written by

the Yucatan Jesuit, Domingo Rodriguez, in 1805, we offer the following

enumeration of the articles destroyed and burned.

5000 Idols, of distinct forms and dimensions.

13 Great stones, that had served as altars.

22 Small stones, of various forms.

27 Rolls of signs and hieroglyphics, on deer skins.

197 Vases, of all dimensions and figures.

Other precious curiosities are spoken of, but we have no description of

them.”[34-*]

Captain Antonio del Rio gives an account of another destruction of Mayan

antiquities, at Huegetan: “The Bishop of Chiapas, Don Francisco Nunez de

la Vega, in his _Diocesan Constitution_, printed at Rome in 1702, says,

that the treasure consisted of some large earthen vases of one piece,

closed with covers of the same material, on which were represented in

stone the figures of the ancient pagans whose names are in the calendar,

with some _chalchihuitls_, which are solid hard stones of a green color,

and other superstitious figures, together with historical works of

Indian origin. These were taken from a cave and given up, when they

were publicly burned in the square Huegetan, on our visit to that

province in 1691.”[35-*]

Prescott also mentions the destruction of manuscripts and other works of

art in Mexico: “The first Arch-Bishop of Mexico, Don Juan de Zumarraga,

a name that should be as immortal as that of Omar, collected these

paintings from every quarter, especially from Tescuco, the most

cultivated capital of Anahuac, and the great depository of the national

archives. He then caused them to be piled up in a mountain heap, as it

was called by the Spanish writers themselves, in the market place of

Tlatelolco, and reduced them all to ashes.”[35-†]

It is not then to be wondered at, that so few original Mayan manuscripts

have escaped and are preserved, when such a spirit of destruction

animated the Spanish priests at the time of the conquest. Mr. Hubert

Howe Bancroft, whom we are happy to recognize as a member of this

Society, in a systematic and exhaustive treatment of the history and

present condition of the Indians of the Pacific States, has presented a

great amount of valuable information, much of which has never before

been offered to the public; and in his wide view, he comprehends

important observations on Central American antiquities. He gives this

account of existing ancient Maya manuscripts or books. “Of the

aboriginal Maya manuscripts, three specimens only, so far as I know,

have been preserved. These are the _Mexican Manuscript No. 2_, of the

Imperial Library at Paris; the _Dresden Codex_, and the _Manuscript

Troano_. Of the first, we only know of its existence, and the

similarity of its characters to those of the other two, and of the

sculptured tablets. The _Dresden Codex_ is preserved in the Royal

Library of Dresden. The _Manuscript Troano_ was found about the year

1865, in Madrid, by the Abbé Brasseur de Bourbourg. Its name comes from

that of its possessor in Madrid, Sr. Tro y Ortolano, and nothing

whatever is known of its origin. The original is written on a strip of

_maguey_ paper, about fourteen feet long, and nine inches wide, the

surface of which is covered with a whitish varnish, on which the figures

are painted in black, red, blue and brown. It is folded fan-like into

thirty-five folds, presenting when shut much the appearance of a modern

large octavo volume; The hieroglyphics cover both sides of the paper,

and the writing is consequently divided into seventy pages, each about

five by nine inches, having been apparently executed after the paper was

folded, so that the folding does not interfere with the written

matter.”[36-*]

It is probable that early manuscripts, as well as others of less

antiquity than the above mentioned, but of great historical importance,

yet remain buried among the archives of the many churches and convents

of Yucatan; and it is also true that a systematic search for them has

never been prosecuted. A thorough examination of ecclesiastical and

antiquarian collections in that country, would be a service to the

students of archæology which ought not to be longer deferred.

The discovery of the continent of America was made near this Peninsula,

and the accounts of early Spanish voyagers contain meagre but still

valuable descriptions of the country, as it appeared at the time it was

first visited by Europeans. It may be interesting to call to mind some

of the circumstances connected with their voyages, and with the first

settlement of Yucatan by the Spaniards, and also to notice briefly some

of the difficulties met with in obtaining a foot-hold in the new world.

Columbus on his fourth and last voyage, in 1502, left the Southern coast

of Cuba, and sailing in a South-westerly direction reached Guanaja, an

island now called Bonacca, one of a group thirty miles distant from

Honduras, and the shores of the western continent. From this island he

sailed southward as far as Panama, and thence returned to Cuba on his

way to Spain, after passing six months on the Northern coasts of Panama.

In 1506 two of Columbus’ companions, De Solis and Pinzon, were again in

the Gulf of Honduras, and examined the coast westward as far as the Gulf

of Dulce, still looking for a passage to the Indian Ocean. Hence they

sailed northward, and discovered a great part of Yucatan, though that

country was not then explored, nor was any landing made.

The first actual exploration was made by Francisco Hernandez de Cordova

in 1517, who landed on the Island Las Mugeres. Here he found stone

towers, and chapels thatched with straw, in which were arranged in order

several idols resembling women--whence the name which the Island

received. The Spaniards were astonished to see, for the first time in

the new world, stone edifices of architectural beauty, and also to

perceive the dress of the natives, who wore shirts and cloaks of white

and colored cotton, with head-dresses of feathers, and were ornamented

with ear drops and jewels of gold and silver. From this island,

Hernandez went to Cape Catoche, which he named from the answer given

him by some of the natives, who, when asked what town it was, answered,

“Cotohe,” that is, a house. A little farther on the Spaniards asked the

name of a large town near by. The natives answered “Tectatan,”

“Tectatan,” which means “I do not understand,” and the Spaniards thought

that this was the name, and have ever since given to the country the

corrupted name Yucatan. Hernandez then went to Campeachy, called Kimpech

by the natives. He landed, and the chief of the town and himself

embraced each other, and he received as presents cloaks, feathers, large

shells, and sea crayfish set in gold and silver, together with

partridges, turtle doves, goslings, cocks, hares, stags and other

animals, which were good to eat, and bread made from Indian corn, and an

abundance of tropical fruits. There was in this place a square stone

tower with steps, on the top of which there was an idol, which had at

its side two cruel animals, represented as if they were desirous of

devouring it. There was also a great serpent forty-seven feet long, cut

in stone, devouring a lion as broad as an ox. This idol was besmeared

with human blood. Champoton was next visited, where the Spaniards were

received in a hostile manner, and were defeated by the natives, who

killed twenty, wounded fifty, and made two prisoners, whom they

afterwards sacrificed. Cordova then returned to Cuba, and reported the

discovery of Yucatan, showed the various utensils in gold and silver

which he had taken from the temple at Kimpech, and declared the wonders

of a country whose culture, edifices and inhabitants, were so different

from all he had previously seen; but he stated that it was necessary to

conquer the natives in order to obtain gold, and the riches which were

in their possession.

Neither Kimpech nor Champoton were under Mexican rule, but there was

frequent traffic between the Mayas and the subjects of the empire of

Anahuac. Diégo Vélasquez de Leon was at that time governor of Cuba, and

he planned another expedition into the rich country just discovered.

Four ships, equipped and placed under the command of Juan de Grijalva,

sailed, in 1518, and first stopped at the Island of Cozumel, which was

then famous with the Yucatan Indians, by reason of an annual pilgrimage

of which its temples were the object. In their progress along the coast,

the navigators saw many small edifices, which they took for towers, but

which were nothing less than altars or teocallis, erected to the gods of

the sea, protectors of the pilgrims. On the fifth day a pyramid came in

view, on the summit of which there was what appeared to be a tower. It

was one of the temples, whose elegant and symmetrical shape made a

profound impression upon all. Near by they saw a great number of Indians

making much noise with drums. Grijalva waited for the morrow before

disembarking, and then setting his forces in battle array, marched

towards the temple, where on arriving he planted the standard of

Castile. Within the sanctuary he found several idols, and the traces of

sacrifice. The chaplain of the fleet celebrated mass before the

astonished natives. It was the first time that this rite had been

performed on the new continent, and the Indians assisted in respectful

silence, although they comprehended nothing of the ceremonies. When the

priest had descended from the altar, the Indians allowed the strangers

peaceably to visit their houses, and brought them an abundance of food

of all kinds. Grijalva then sailed along the coast of Yucatan. The

astonishment of the Spaniards at the aspect of the elegant buildings,

whose construction gave them a high idea of the civilization of the

country, increased as they advanced. The architecture appeared to them

much superior to anything they had hitherto met with in the new world,

and they cried out with their commander that they had found a New Spain,

which name has remained, and from Yucatan has been applied to the

neighboring regions in that part of the American continent. Grijalva

found the cities and villages of the South-western coast like those he

had already seen, and the natives resembled those of the north and east

in dress and manners. But at Champoton the Indians were, as before,

hostile, and were ready to use their arms to repel peaceful advances as

well as aggressions. The Spaniards succeeded however, after a bloody

struggle, in gaining possession of Champoton and putting the Indians to

flight. Thence Grijalva went southward to the river Tobasco, and held an

interview with the Lord of Centla, who cordially received him, and

presents were mutually exchanged.

Still the native nobles were not slow in showing that they were troubled

at the presence of the strangers. Many times they indicated with the

finger the Western country, and repeated with emphasis the word, at that

time mysterious to Europeans, Culhua, signifying Mexico. The fleet then

sailed northward, exploring the coast of Mexico as far as Vera Cruz,

visiting several maritime towns. Francisco de Montejo, afterwards so

celebrated in Yucatan history, was the first European to place his foot

upon the soil of Mexico. Here, Grijalva’s intercourse with the natives

was of the most friendly description, and a system of barter was

established, by which in exchange for articles of Spanish manufacture,

pieces of native gold, a variety of golden ornaments enriched with

precious stones, and a quantity of cotton mantles and other garments,

were obtained. Intending to prosecute his discoveries further, Grijalva

despatched these objects to Vélasquez at Cuba, in a ship commanded by

Pedro de Alvarado, who also took charge of the sick and wounded of the

expedition. Grijalva himself then ascended the Mexican coast as far as

Panuco (the present Tampico), whence he returned to Cuba. By this

expedition the external form of Yucatan was exactly ascertained, and the

existence of the more powerful and extensive empire of Mexico was made

known.

Upon the arrival of Alvarado at Cuba, bringing wonderful accounts of his

discoveries in Yucatan and Mexico, together with the valuable

curiosities he had obtained in that country, Vélasquez was greatly

pleased with the results of the expedition; but was still considerably

disappointed that Grijalva had neglected one of the chief purposes of

his voyage, namely, that of founding a colony in the newly discovered

country. Another expedition was resolved on for the purpose of

establishing a permanent foot-hold in the new territory, and the command

was intrusted to Hernando Cortez. This renowned captain sailed from

Havana, February 19, 1519, with a fleet of nine vessels, which were to

rendezvous at the Island of Cozumel. On landing, Cortez pursued a

pacific course towards the natives, but endeavored to substitute the

Roman Catholic religion for the idolatrous rites which prevailed in the

several temples of that sacred Island. He found it easier to induce the

natives to accept new images than to give up those which they had

hitherto worshipped. After charging the Indians to observe the religious

ceremonies which he had prescribed, and receiving a promise of

compliance with his wishes, Cortez again sailed and doubled cape

Catoche, following the contour of the gulf as far south as the river

Tobasco. Here, disembarking, notwithstanding the objections of the

Indians, he took possession of Centla, a town remarkable for its extent

and population, and a centre of trade with the neighboring empire of

Mexico, whence were obtained much tribute and riches. After remaining

there long enough to engage in a sanguinary battle, which ended in a

decisive victory for the Spaniards, Cortez reëmbarked and went forward

to his famous conquest of Mexico.

From the time when Cortez left the river Tobasco, his mind was fixed

upon the attractions of the more distant land of Mexico, and not upon

the prosecution of further discoveries upon the Western shores of

Yucatan; and until 1524, for a period of more than five years, this

peninsula remained unnoticed by the Spaniards. Then Cortez left Mexico,

which he had already subjugated, for a journey of discovery to Honduras,

and for the purpose of calling to account, for insubordination and

usurpation of authority, Cristoval de Olid, whom he had previously sent

to that region from Vera Cruz. He received from the princes of Xicalanco

and Tobasco maps and charts, giving the natural features of the country,

and the limits of the various States. His march lay through the Southern

boundaries of the great Mayan empire. Great were the privations of this

overland march, which passed through a desolate and uninhabited region,

and near the ruins of Palenque, but none of the historians of the

expedition take notice of the remains. When Cortez finally arrived at

Nito, a town on the border of Honduras, he received tidings of the death

of Cristoval de Olid, and that his coming would be hailed with joy by

the Spanish troops stationed there, who were now without a leader. From

the arrival of Cortez at Nito, the association of his name with the

province of Yucatan is at an end, and the further history of that

peninsula was developed by those who afterwards undertook the conquest

of that country.

Francisco de Montejo was a native of Salamanca, in Spain, of noble

descent and considerable wealth. He had been among the first attracted

to the new world, and accompanied the expedition of Grijalva to Yucatan

in 1518, and that of Cortez in 1519. By Cortez this captain was twice

sent to Spain from Mexico, with despatches and presents for the Emperor,

Charles V. In the year 1527, Montejo solicited the government of

Yucatan, in order to conquer and pacificate that country, and received

permission to conquer and people the islands of Yucatan and Cozumel, at

his own cost. He was to exercise the office of Governor and Captain

General for life, with the title of Adelantado, which latter office at

his death should descend to his heirs and successors forever. Montejo

disposed of his hereditary property, and with the money thus raised

embarked with about four hundred troops, exclusive of sailors, and set

sail from Spain for the conquest of Yucatan. Landing at Cozumel, and

afterwards at some point on the North-eastern coast of the peninsula,

Montejo met with determined resistance from the natives; and a battle

took place at Aké, in which one hundred and fifty Spaniards were killed,

and nearly all the remainder were wounded, or worn out with fatigue.

Fortunately, the Indians did not follow the retreating survivors into

their entrenchments, or they would have exterminated the Spaniards. The

remnants of this force next appeared at Campeachy, where they

established a precarious settlement, and were at last obliged to

withdraw, so that in 1535 not a Spaniard remained in Yucatan.

Don Francisco de Montejo, son of the Adelantado, was sent by his father

from Tobasco, in 1537, to attempt again the conquest of Yucatan. He made

a settlement at Champoton, and after two years of the most disheartening

experiences at this place, a better fortune opened to the Spaniards. The

veteran Montejo made over to his son all the powers given to him by the

Emperor, together with the title of Adelantado; and the new governor

established himself at Kimpech in 1540, where he founded a city, calling

it San Francisco de Campeachy. From thence an expedition went northward

to the Indian town Tihoo, and a settlement was made, which was attacked

by an immense body of natives. The small band of Spaniards, a little

more than two hundred in all, were successful in holding their ground,

and, turning the tide of battle, pursued their retreating foes, and

inflicted upon them great slaughter. The Indians were completely routed,

and never again rallied for a general battle. The conquerors founded the

present city of Mérida on the site of the Indian town, with all legal

formalities, in January, 1542.[44-*]

But though conquered the Indians were not subjugated. They cherished an

inveterate hatred of the Spaniards, which manifested itself on every

possible occasion, and it required the utmost watchfulness and energy

to suppress the insurrections which from time to time broke out; and the

complete pacification of Yucatan was not secured before the year 1547.

Hon. Lewis H. Morgan, in an interesting article in the North American

Review, entitled “_Montezuma’s Dinner_,” makes the statement that

“American aboriginal history is based upon a misconception of Indian

life which has remained substantially unquestioned to the present hour.”

He considers that the accounts of Spanish writers were filled with

extravagancies, exaggerations and absurdities, and that the grand

terminology of the old world, created under despotic and monarchial

institutions, was drawn upon to explain the social and political

condition of the Indian races. He states, that while “the histories of

Spanish America may be trusted in whatever relates to the acts of the

Spaniards, and to the acts and personal characteristics of the Indians;

in whatever relates to Indian society and government, their social

relations and plan of life, they are wholly worthless, because they

learned nothing and knew nothing of either.” On the other hand, we are

told that “Indian society could be explained as completely, and

understood as perfectly, as the civilized society of Europe or America,

by finding its exact organization.”[45-*] Mr. Morgan proposes to

accomplish this result by the study of the manners and customs of Indian

races whose histories are better known. In the familiar habits of the

Iroquois, and their practice as to communism of living, and the

construction of their dwellings, Mr. Morgan finds the key to all the

palatial edifices encountered by Cortez on his invasion of Mexico: and

he wishes to include, also, the magnificent remains in the Mayan

territory. He would have us believe, that the highly ornamental stone

structures of Uxmal, Chichen-Itza, and Palenque, were but joint tenement

houses, which should be studied with attention to the usages of Indian

tribes of which we have a more certain record, and not from

contemporaneous historical accounts of eye witnesses.

In answer to Mr. Morgan’s line of argument, it may be said, that the