*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK 73960 ***

THE MAN WHO HATED HIMSELF

By Walt Coburn

A powerful story of the Montana cattletrails

and the Great Blizzard of ’86

Every stockman in the northwest recalls the hard winter of ’86-’87. It

broke most of them. One cattleman, spending his winter in the South,

wrote back to his ranch to inquire how his stuff was wintering. His line

rider took a pencil and drew the picture of a starving cow hung up in

the drifts. Under it he wrote:

Waiting for a chinook. The last of the five thousand.

The man who drew that picture was Charlie Russell, the daddy of them all

when it came to putting the cow and the horse and the Indian and the

cowpuncher on canvas or in clay. But in ’86 Charlie was a cowpuncher.

This is not a story about Charlie Russell. He is mentioned no more in

the tale. I speak of him here because when a cowman of Montana recalls

the winter of ’86 he invariably mentions that picture of Charlie

Russell’s as an illustration for his tale of hardship. It tells better

than any words the bitter curse of that hard winter.

The Circle C outfit made their last shipment of steers along about the

first of November that fall. It was spitting snow when they finished

loading. The cattle train pulled out for Chicago. The boys rode back to

where the roundup wagon was camped on Main Alkali. They gulped down hot

food and black coffee, caught out their town horses and headed for

Malta.

As they jogged along the road with their ears tied up with silk

handkerchiefs, heads bent against the raw wind, big Buck Bell rode up

alongside the wagon boss.

“Winter’s done come, Horace,” grunted Buck, fashioning a cigaret with

numbing fingers.

“Shore has,” returned Horace, humped across his saddle horn.

“Makes a man wonder what’s become of his summer’s wages,” Buck led up to

his subject.

Horace nodded a trifle absently. He was wondering how he’d get his mess

wagon loaded and started for the ranch before the cook got too drunk to

handle his four lines.

“How’s chances fer a winter’s job ridin’ line, Horace?” Buck tried to

keep the eager tremor out of his voice.

“We’re full handed fer the winter, Bell. You should ’a’ tackled me a

month ago.”

“A month ago,” said Buck Bell with grim humor, “I was fatter’n a bear in

berry season. Had a thousand dollars. Had a idee I was a top hand at

draw poker; The nighthawk took me fer my roll.”

This story of tough luck was not a new one to the ears of the wagon

boss. It is a tale as old as the oldest cow hand. Horace, still thinking

of the cook, missed the flicker of disappointment in Buck Bell’s snow

bitten eyes. He failed to see the beaten droop of the big boned

shoulders inadequately clothed in a soiled flannel shirt and two

undershirts. Buck didn’t own an overcoat. His boots were rusty and he

kicked his toes against his stirrups as he rode, by way of restoring

circulation.

* * * * *

“Looks like when a man begun gittin’ white headed,” said Horace as they

dropped down the ridge toward town, “he’d have sense enough to save a

winter stake.”

He did not mean to be unkind. There wasn’t a mean drop of blood in the

cow boss’s veins. He was sorry for Buck Bell and hid his softer emotions

under the words he now mumbled into the upturned collar of a threadbare

coat. Truthfully speaking, Horace himself was prodigal as the rest of

the cowpuncher clan.

Buck took a last pull at the bit of stub of cigaret and threw it away.

Then he chuckled softly. They were riding down the lane that approached

town. To the left of them was the Malta graveyard, the wooden slabs

whitening with the first snow.

“What struck you as bein’ so comical, Buck?”

“Just thinkin’ how them boys planted in yonder boothill don’t need worry

no more about winter jobs and coonskin coats they ain’t got the coin to

buy. I kin name three-four that I bet is plenty warm where they went.”

They rode into town and put their horses in the feed barn. The stalls

were filling with Circle C horses. There was an unwritten law of the

outfit that a man must stable his horse before he got drunk.

Over at Dick Powell’s place the boys were paid off. Dick, saloon man and

sheriff, voiced his friendly warning.

“The town’s your’n, boys, Take care of ’er.”

The hard earned money went into swift circulation. The tin horn gamblers

opened up their games. Bartenders set up free drinks at proper intervals

to the laughing, cussing, free handed men who lined the bar and swapped

yarns and thawed out.

Boot heels clicked on the pine board floors. Spurs jingled along the

streets.

“Can’t spend’er all in one place.”

They moved along to the next saloon. Crumpled banknotes lay along the

bar. The men greeted old friends. Jovial bartenders, most of them old

time cowpunchers, wiped right hands on soiled aprons and voiced profane

welcome.

Fiddles squeaked above the voices loosened by the whisky. Tin pan pianos

banged. Lights defied the coming dusk of early night. There would be no

night guard to stand tonight. No long circle to ride in the early dawn.

While their money lasted these cowboys owned the town.

Buck Bell found the nighthawk sitting in a monte game.

“Here’s that fifty dollars you still got comin’, Cotton Eye.”

The nighthawk looked up, grinned and shook his head.

“To hell with you an’ your fifty, Buck. Pay me half when you die. The

rest when you come back. I’m winnin’ off this gamblin’ man.”

Buck grunted an indistinct thanks and clumped up to the bar.

“A little red licker, Dick. Give the boys what they want. Wake up that

sheepherder in the corner and tell the gentleman that ol’ Buck Bell is

in town. I’m a red eyed wolf from Bitter Crick and it’s my night to

howl.” Whereupon he howled long and loud with a quivering, high keyed

sadness in his voice.

* * * * *

“See you later,” Buck said as he moved on out and along the street.

The wind moaned darkly down the lonesome lane between the rows of

saloons and stores. He stood with bowed legs spread wide, thumbs hung in

his sagging cartridge belt, leaning a little against the storm. His howl

was blotted out in a flurry of snow that was ushering in the long

winter. Buck felt sad in spite of the dozen drinks under his belt. Sad

and lonesome and restless. He belonged down in Texas and he was a long

way from home. He had aimed to go back home this winter, wearing store

clothes and with coin in his pockets. But Cotton Eye had cleaned him. He

crossed over to Long Henry’s and was promptly pulled up to the bar by

several celebrants. Buck tossed out a ten dollar bill with the air of a

man who scorns money. Somebody was singing “Sam Bass”.

“Sam Bass” is a ballad that extolls the deeds of that notorious Texas

outlaw. The old time outlaw has always held a place in the hearts of the

cowpunchers. His vices are buried, his virtues, real or imaginary, live

on in cowland saga.

“Sam first came to Texas a cowboy for to be--

A kinder hearted feller you seldom ever see!”

Buck Bell twirled his whisky glass between thumb and forefinger. The

singer had a good voice and his audience was mellow and prone to the

sentiment that has to do with white haired mothers, golden haired

sweethearts and generosity of dying outlaws.

“Sam met his fate at Round Rock, July the twenty-first;

They pierced poor Sam with rifle balls and emptied out his purse.

“Jim had borrowed Sam’s good gold and didn’t want to pay,

So the only shot he saw, was to give poor Sam away.

He sold out Sam . . .

Buck Bell nodded at his dim reflection in the mirror above the back bar.

“I usta work clost to Round Rock,” he told the man next to him.

He downed his drink at one gulp and reached for the bar bottle as it

came down along the line. He became more quiet, more thoughtful, as the

night wore on. That haunted restlessness drove him out to the deserted

street. He drifted, alone and wrapped in brooding thought, into

Cavanaugh’s.

The negro piano player knew the song of Sam Bass. He sang it through

three times for Buck. Buck gave him ten dollars. Only ten more remained

in his overalls pocket.

* * * * *

After many more drinks Buck Bell started for a place across the tracks.

His last ten was spent. His heart was as empty as his pockets. The

mournful shriek of a locomotive made him shiver as he halted in the lee

of the station to light a cigaret. The train dispatcher stepped out of

the lighted telegraph office, an eyeshade across his forehead, train

orders in his hand. He did not see the tall form of Buck Bell leaning a

little unsteadily in the darkness just to one side of the locomotive

headlight.

No. 3 squealed to a halt to deposit two sleepy traveling drummers. The

door of the express car opened. The armed messenger dropped a heavy iron

box on the waiting truck alongside the car. The train dispatcher was now

signing for the box. The drummers hurried for the Malta House.

“Payroll for the mines,” the express messenger, explained. “Wish I had

that much. I’d quit riding these damn’ night runs. Blizzard comin’.”

The door of the express car slid shut. A yellow lantern circled in the

night. The train pulled out slowly and the dispatcher wheeled away the

truck with its steel box.

The wheels of the truck creaked its dismal passage. The form of Buck

Bell moved in a blackness made more opaque by the departure of the train

lights. The man was pushing the truck within arm’s reach of the tall

cowboy.

Buck lifted his gun from its old scabbard. He balanced its weight in his

hand, moved out of his tracks. Swung the long barrel in a swift arc. The

man wheeling the truck slumped down gently, an indistinct lump on the

deserted platform.

Buck Bell moved swiftly now. He picked the steel box up in his arms and

ran down the tracks. He did not halt until he reached the stockyards, a

mile or more from town. He hid the box under the loading chute, then

started back.

The walk in the cold air had driven the whisky fog from his brain. Buck

was sober now. The sadness, the brooding restlessness, had gone and in

its place came swift regrets. He fought down those regrets as best he

could. He’d been a fool to do it, but he was into it now. He’d hang and

rattle. Play ’er out as the cards fell and ask no man for better than

even odds. He wondered how hard he’d hit that depot feller. Can’t let a

man lay out in the cold that way. Besides, there was the trains to

attend to.

But, as he circled the depot, he saw the sheriff and the train

dispatcher talking earnestly inside the lighted telegraph and ticket

office. Buck moved away, across to Dick Powell’s place. Nobody took

notice of his entrance as he slipped in the back door and dropped into a

chair by the stove. Then somebody called the house up for a drink and

Buck joined the crowd. He had not been missed.

“How’s things stackin’ up, Buck?” It was old Horace who voiced the

question. “Need a little money? I was talkin’ to the Old Gent and he

said to let you have what you need. You kin come back and work it out in

the spring. It ain’t every man I’d do that fer. But like I was tellin’

the Old Gent, you’re on the square and kin be depended on.”

Buck’s mouth opened, then closed without saying a word. He had been on

the verge of telling the wagon boss the whole thing. Until now, Buck

Bell had accepted the trust of his fellowmen as a matter of course. Now,

well, now it was all over. He was beginning to pay already for his

crime.

“I’ll just make ’er out fer a hundred dollars, Buck.”

Horace was misinterpreting the cowboy’s silence. Buck shook his head.

“I’d ruther not, Horace. I’ll make ’er somehow. It’s right white of you

and the Old Gent. I won’t fergit it.”

* * * * *

The sheriff came in, an icy gust of wind and snow following him inside

the lamplit, smoke hazed saloon.

Dick Powell was a blunt statured man, husky, reddish of hair, with keen

gray eyes and a drooping mustache. A good natured sort of fellow who was

rated as a crackerjack cow hand. The grin on Dick’s mouth held a grim

twist as his eyes swept the crowd with slow deliberation.

“Belly up to the mahogany, Dick,” invited some one.

Dick Powell did not seem to hear. A hush fell over the gathering. The

fiddle in the hands of a Cree breed squeaked thinly and went silent. The

bartender, from force of habit, reached for the sawed off shotgun under

the bar.

“Boys,” said the blocky sheriff, his voice heavy with sadness, rather

than anger, “there’s a damn’ skunk amongst us tonight. When you boys

rode in, I give you the run of the town. A man hates to think he has to

watch boys that he’s worked with in the wet and cold and hot weather. I

never thought a Circle C man would coyote on me.”

“What the hell you drivin’ at, Dick?” asked Horace, his mild eyes

glinting a little.

“Some polecat knocked the depot man on the head and got off with five

thousand dollars, that’s all.”

“Where did that key pounder ever git five thousand bucks?” asked some

one.

“Payroll fer the Landusky mine. Five thousand in cash.”

“Well,” drawled Cotton Eye, the nighthawk, “I reckon them mine folks

will keep on runnin’ things just the same. Have a drink and fergit it.”

“Whoever lifted that roll won’t have to worry none about forkin’ hay and

openin’ water holes this winter,” chuckled another cowboy.

“Dad burn the luck,” complained a third, “why didn’t I think about

glaumin’ that payroll? Now I gotta break out of a early mornin’ from now

till spring, shovelin’ hay into a lot o’ bawlin’ dogies. Some gents gits

all the luck.”

But for all their banter, they felt uneasy. Who among them had stolen

that five thousand dollars? Oddly enough, no man blamed the thief. They

rather admired his ingenuity. He had made a lucky haul.

“Well, Dick,” said Horace slowly, “whoever done it, must ’a’ been blind

drunk. You know every man in the outfit. There ain’t one rotten egg in

the bunch. Say, how do you know it wa’n’t some tramp er some stray miner

that done it?”

“The depot man heard his spurs jingle, so he says,” growled the sheriff,

“just before he got beefed. It was some cow hand. And outside of you

boys there ain’t a cowboy in town. He heard them spurs.”

“Got ary idee who might ’a’ done it?” asked Horace.

“If I have, I’ll keep it to myself,” came the tart reply. “I look to you

boys to lend me a hand and all I git is some horrawin’.”

“No need to git hot about it,” grinned the wagon boss, toying with his

drink.

The sheriff ignored that remark and turned to his bartender.

“Was all of these men in the place at midnight when No. 3 come in?”

The bartender smoothed his bald head in grave thought. He had taken a

goodly amount of drinks since the boys got in. Owl eyed, he tallied the

crowd.

“Near as I kin recollect, Dick, not a man o’ them has left since I come

back from supper at eleven.”

“Then that alibis this bunch of cow dodgers,” and the sheriff moved on

out and down the street.

* * * * *

The robbery gave the cowpunchers a meaty topic for talk--talk and more

drinks. They hit upon the idea of following Dick Powell in his

sleuthing.

From one saloon to the next they waddled in the wake of the annoyed

sheriff. The crowd had taken on numbers until by the time they reached

the Bloody Heart the entire outfit was crowded into the saloon.

Various bartenders had furnished iron-clad alibis for every Circle C

man. Powell gave up in disgust and slipped away from the throng, which

was growing somewhat boisterous. Horace followed the sheriff out the

back door. Twenty-five cowpunchers set about to make the most of the

momentous occasion.

Months of hard work in the saddle and branding corrals without a

holiday, long days from the crack of dawn until dark, with two hours

night guard for good measure, had starved them for a little fun.

These men belonged to a breed that has no equal. For forty dollars a

month and grub they ride mean horses, face death and hunger and thirst

and cold and bitter discomforts. They ask no favors, whine out no

complaint, taking the good along with the bad. It is all in a day’s

work. Most of them were cowmen at twelve years of age. At sixty there

would be much of the boy left in their big hearts. It is not for those

who have not known their breed to censure their faults. They lived

according to their lights.

John Law and his rules meant little in their lives. They had a way of

settling personal affairs, those men who roamed the West in the Eighties

when the country needed them.

So they held kangaroo court. The bartender at the Bloody Heart was found

guilty and fined several rounds of drinks. Then they moved on to the

next saloon and again held court. Another dispenser of redeye was found

guilty. Guilty as hell, by ballot. The fine was duly paid in liquid

form. And at daybreak they had routed the sheriff from his warm bed,

stood him up on the bar, clad in a knee length nightshirt, boots, hat

and a cold cigaret. Ballots were passed, signed and dropped in Dick’s

hat. He read them, one by one.

“Guilty as hell.”

“Gash damn’ you bonehead, misfit, loco idiots!”

But he paid the fine, setting out the glasses and bottle with his own

hand.

It was a large night. Guns popped jubilant greeting to a day that held

no hard ride after stray cattle.

Most of them were flat broke. Cotton Eye, the bloated financier, had

lost his money and hocked his spurs for a bottle to take along. Then he

engaged the bartender in conversation while a confederate stole back the

spurs.

Horace gathered his men one, by one, mounted them, and started them out

of town. They bucked their horses down the street, emptying their guns

at a leaden sky. Behind them was their night’s pleasure. Ahead lay the

dread winter.

* * * * *

Buck Bell got his private horse from the barn. Because he owned no

overcoat, he donned his slicker and wrapped his feet in strips of

gunnysack. Alone, his hat pulled down across his eyes, his ungloved

hands shoved down against the saddle cantle, he rode out of town.

As he neared the stockyards he glanced about. No living thing moved in

the snow swept world that met his eye. He swung off his horse and

dragged the steel box from under the loading chute. A heavy padlock

fastened it. Buck drew his .45 and shot off the lock. His stiff fingers

pried up the lid. There lay the banknotes in piles bound with wide

rubber bands. He shoved the money into the deep pockets of his angora

chaps. Then he buried the empty metal box in the débris under the chute.

Five minutes later he rode on again into the storm. He looked old and

sadly troubled. The bitter cold was pinching the color from his face. He

was a little sick from the liquor that he had drunk. Sick and lonesome.

Through the lane and past the graveyard, on to the wind swept benchland,

headed south toward the badlands of the Missouri River, almost a hundred

miles away. With the wind at his back, Buck Bell drifted. His heart was

as heavy as the leaden sky. Ahead of him rolled a giant tumbleweed. On

and on, across the bench, grotesque, almost alive, blown along by the

north wind. Headed south.

In the pockets of his black chaps was stowed more money than he had ever

seen or even dreamed of. There was not a chance of the theft being

fastened to him. It had been easy, almost too easy to seem true. With

five thousand dollars a man could buy a good bunch of cattle down in New

Mexico or Arizona. Buck was cowman enough to make a herd pay. It would

mean that he no longer need work for wages. For forty a month ... Forty

into five thousand. Buck was a good hand at figures. One hundred and

twenty-five months. Ten years and more, even if a man didn’t spend a

dime for poker or redeye or smokin’--or clothes. Socks and such. He had

sold his bed for twenty dollars. That twenty was in his vest pocket now.

He had kept it separated from the other money--the money he had stolen.

“Sam Bass was born in Indiana; it was his native home....”

The song, high pitched, quavering, drifted along the wind from behind

Buck, blurred a little in the flurry of hard snow that swirled across

the ground like white sand. Buck halted as the singer came up out of the

storm. It was Dick Powell, the sheriff.

* * * * *

Something hot scalded Buck Bell’s heart as the rider came alongside. Had

the sheriff somehow found him out? Buck almost hoped so. But Powell

grinned as easy greeting. He was warmly clad in chaps, overshoes and a

buffalo coat. The stock of a carbine jutted from his saddle scabbard.

“You look fer all the world like a bull that’s been whipped outa the

herd, Bell. Here, see what this’ll do to you.”

He passed over a quart of whisky. They drank together and rode on with

the storm.

“Trailin’ that gent that done the robbery, Dick?”

The sheriff grunted into his fur collar.

“Trailin’ hell! Whoever done it didn’t leave a sign. But mark my words,

Bell, he’ll give hisself away.”

“How?”

Buck Bell slapped his cold hands against the slicker to beat the blood

into circulation.

“Here, take these.” The sheriff pulled a pair of yarn mitts from his

pocket. “I brung along an extra pair. The missus knit ’em.”

Buck pulled on the red mittens, mumbling his gratitude.

“How?” The sheriff replied to his question. “Well, it’s thisaway, Bell.

I know every man that was in town that night. I know where each man will

be workin’ this winter. Horace gimme their names and what camps they’d

be at. I wired fer the serial number of them stolen banknotes. When that

money begins goin’ into circulation, I’ll nab my man. Er if ary man

quits this range, I’ll be follerin’ him. I’ll have the other towns

posted. He’s corralled.”

The sheriff consulted a little book.

“Here’s the list. Stuart and Contway at Big Warm. Howe and Smith at

Little Warm. You and Cotton Eye at Rocky Point, down on the Missouri.

And so on.”

He shoved the book back into his pocket. Buck’s head was lowered as he

fumbled with clumsy hands at a witch’s knot in his horse’s mane. His

brain was working swiftly. Why had Horace lied? Why had the wagon boss

told the sheriff that he, Buck Bell, was going into a line camp at Rocky

Point?

“I wouldn’t be tellin’ this to everybody, understand,” continued the

sheriff. “I know I kin trust you, Bell.”

If the sheriff had taken a sharp knife and struck the cowpuncher in the

back he could not have hurt Buck Bell more than he did when he spoke

those words.

They rode on in silence. Buck was chilled to the bone by the wind; it

bit through his inadequate clothing. Dick urged the bottle on him to

warm his blood.

“I got some stuff that’ll be driftin’ with the storms this winter, Bell.

I spoke to the Old Gent about it. He said it’d be all right if you boys

kinda kept an eye on ’em and feed a few if need be.”

“Shore,” mumbled Buck. “Shore thing.”

Their trails parted a little farther on. The sheriff made Buck take his

overshoes and the bottle.

“I’ll be back home in a couple o’ hours. Don’t be a damn’ fool, Bell. So

long. Good luck, old-timer. See you next spring when the chinook melts

you outa the bad lands.”

When they had parted Buck rode on, the ache in his heart more bitter

than before. The words of the sheriff’s song came drifting back out of

the storm--the song of Sam Bass.

“. . . Sam he is a corpse and six foot under clay.”

Buck stayed that night at a line camp, and pushed on the next morning.

He kept wondering why Horace had lied. It hung like a sand burr in his

thoughts all that day. He stopped late the next afternoon at a horse

camp; and because they were short handed, Buck worked there a week. Then

he drifted on once more, refusing a cent for his labors. It was the

ethics of the grub line that forbade his accepting payment. They had

given him and his horse food and shelter. He asked no more, though the

work had been hard and he had eaten but two meals each day. Breakfast

before they rode away; supper when they came in after dark. He had made

the biscuits, helped with the dishes, and split wood, to boot. And he

had given them what was left of the whisky.

* * * * *

Because Rocky Point lay along his route to somewhere south, he rode up

there one evening at dusk.

A saddled horse was humped in the lee of the shed. Hollow eyed cattle

bawled in the corral. No smoke came from the little log cabin. Filled

with grave misgivings, Buck Bell stepped into the cabin. The moan of a

man in pain came out of its dark interior. He found Cotton Eye lying

fully clothed in bed, his leg broken between the ankle and knee. He had

been like that since the day before, he told Buck through set teeth.

“Horse fell on me, comin’ up the river.”

Buck built the fire and made the crippled man as comfortable as

possible. Then he took care of the horses and scattered hay for the

gaunt cattle. When he came back to the cabin, he hid his fears under a

careless banter.

“I’ll throw some soup into you, Cotton Eye. And coffee. Now roll over on

your back and cuss me while I git this boot cut off. I’ll be as gentle

as a cow with her first calf, pardner.”

Those men of the frontier were steady of hand and ingenious of brain.

Broken bones and gunshot wounds were not uncommon. A man needed to know

the rudiments of crude surgery in those days when doctors were few and

far between.

There was no sleep for either man that night. Buck fashioned a sling to

hold the suffering man while he pulled the fractured bone into place.

The erstwhile nighthawk groaned. Buck swore softly as he labored. He

splinted the leg with stout willow sticks and strips of tanned rawhide

saddle strings. Beads of sweat covered the drawn face of Cotton Eye. He

lay back, whimpering a little through clenched teeth, sick and faint,

but game enough. Buck held a cup of black coffee to his mouth.

“She’s all over but the knittin’, pard. Here’s a cigaroot. She’ll hurt

like hell fer a spell, but it’s a clean break and orter heal fast. I’ll

run the show till you git well.”

“I’d ’a’ died if you hadn’t come along, Buck.”

“Mebbe.”

Buck built up the fire. His chaps with their precious store of money

hung on a wooden peg with his bridle. Now and then he glanced that way,

his lips smiling without humor.

“You saved my life, Buck. I ain’t fergittin’.”

“You better try to sleep, feller,” grunted Buck.

Cotton Eye lay there, a little flushed with fever, his eyes brighter

than they should have been.

“I wonder, Buck, if you’d be doin’ this fer me if you knowed.”

“Knowed what, Cotton Eye?”

“That money I won off you. That deck was marked.”

“Shore thing,” nodded Buck Bell, “I knowed that. But a man’s gotta have

some kinda excitement around a cow camp, even if it’s playin’ poker with

a marked deck. I was ketchin’ on to the markin’s about the time I went

broke.”

Cotton Eye was delirious by morning. Buck was forced to tie the man down

while he fed and watered the cattle. Because there was only one bed,

Buck had made out with the saddle blankets and the sick man’s overcoat.

* * * * *

During the days that followed Buck Bell did the work of five men. He

chopped wood, cooked, and nursed Cotton Eye, whose fever went down

slowly. He rode out each day, gathering poor cows that were too weak to

rustle. He hooked up the work team and hauled hay, scattering it in a

wide circle outside the corral. He opened the water hole twice a day. He

puttered about the cabin, fixing it for the long winter, and forced a

cheerfulness into the chatter that he flung at Cotton Eye. When he

finally crawled into his improvised bed, fully clothed save for hat and

boots, he was too weary to mind the cold much.

He killed a beef one evening. That night he brought in a square piece of

the hide and worked on it with his pocket knife.

“Let’s have that good leg o’ your’n, pardner.” Buck wrapped the hide

about the leg, nodded, marked it with his knife and took the hide back

to his seat by the fire.

“Them splints kin come off in a day er so. I’m fixin’ a sorter casin’ to

fit around that game laig. This hide’ll be plenty hard and we’ll lace

it, savvy? Padded with the felt from a man’s hat, she’ll make a cast

that’ll be useful and right ornamental, with the hair on the outside.

I’m stretchin’ it around this willer pole to make ’er smooth.”

Buck tanned the rest of the hide and made himself moccasins and a coat

that was ill fitting but warm enough. He killed a blacktail buck and

they feasted on venison. Buck spent his evenings tanning the hide. The

rawhide cast, smooth and hard and padded with felt from Buck’s hat, now

replaced the willow splints. Buck wore a cap made out of a piece of

Hudson’s Bay blanket. He refused the offer of Cotton Eye’s clothes.

With December came real winter--the hardest winter the cowmen in Montana

have ever known. The hay was giving out. Buck worked on a snowplow. The

cattle in the field grew in number each day. Gaunt flanked, hollow eyed,

bawling as they trained at a stubborn walk with the storm.

Gray days. White days. Bitter days. The cattle drifting down into the

badlands. Even the big native steers were finding it hard to paw to feed

under the crusted snow.

Buck’s black chaps no longer banked his stolen money. He had buried the

stuff in a corner of the cow shed, wrapped carefully in his slicker. His

daylight labors brought peace of mind. But sometimes he lay awake, far

into the night, haunted by thoughts of the buried wealth. The dream of a

cow outfit of his own was replaced by the black nightmare of his theft.

He was tempted a hundred times to share the burden of his guilt with

Cotton Eye who was now hobbling about on crutches made of forked sticks

wrapped and padded with deerskin.

“Wish I could git word out to the ranch,” said Buck, “This hay ain’t

gonna last. The only shot, if this keeps up, is to drift south o’ the

river where the shelter is better. Mebbe train out from there. They

could buy hay at Lewistown and Gilt Edge. I had to kill three more

calves today. Cows didn’t have milk to feed the li’l beggars. Hear the

cows a-bawlin’? Hell, ain’t it?”

The haystacks were becoming fewer. Buck and his crippled partner found

it hard to fill the long silences that fell over them. Cotton Eye

hobbled about now, getting the meals and washing dishes. He scraped the

thick frost from the window and would sit there, smoking and watching

Buck Bell pitch hay sparingly to the starving cattle. When Buck saddled

his horse and rode back into the breaks to bring in more stumbling,

gaunt steers and cows, Cotton Eye would curse with futile fury at his

aching leg.

“Brung in three more o’ Dick Powell’s steers today. Weak as hell.

Three-four Circle Diamond cows, another Square steer, one er two Bear

Paw Pool strays, and the Widder Brown’s Jersey milk cow. The widder sets

a heap o’ store by that cow. It must be shore a-stormin’ up on the

ridges, to drift that stuff into the breaks. If this keeps up, there

won’t be a cow left in the country.”

“You was sayin’ something about gettin’ word to the ranch, Buck. I kin

make out to ride now. I’d like to tackle it. Ain’t doin’ no good here.”

“If you’re plumb sure you kin make it, pardner?”

“Shore thing, I kin. I’ll pull out in the mornin’.”

* * * * *

Buck wrapped the injured leg in a blanket and Cotton Eye rode away in

the gray dawn. Buck grinned a farewell. When Cotton Eye was gone, Buck

tried to whistle away the gnawing loneliness. He worked feverishly, not

even taking a few minutes off at noon for his usual coffee and beans and

meat. Now and then, when his chores took him past the corner of the shed

where the stolen money had been buried, he would quicken his pace, as a

man afraid of ghosts might pass with haste by a grave.

“Why did Horace lie?” he asked himself a thousand and one times.

“Because Horace knowed who done the robbery!” came the still answer out

of each night’s darkness.

Cotton Eye had left his bed and his warsack filled with a few clothes

and knicknacks. Delving into the sack for a needle and thread one day, a

week or so after Cotton Eye’s departure, Buck came upon a large envelope

of heavy paper. He emptied its contents of saddle wax and thread and

harness needles and awl. He sat there, smiling softly, the worried frown

momentarily gone from his forehead.

“I’ll do it. I’ll use this envelope to hold the money. Else I’ll be

plumb crazy before spring. I’ll send the money to Horace, first man that

passes along.”

He spent an evening composing a laborious letter to the Circle C wagon

boss. That night he slept without tossing and dreaming. And with the

first streak of dawn he was out in the shed with pick and shovel,

digging in the corner. With hands that shook with eagerness, he undid

the slicker. A choking cry broke from his pulsing throat. The money was

gone. All of it. The slicker held nothing but some scraps of old

newspaper, rudely cut and bundled in imitation of the banknotes.

For a long time Buck squatted there on the ground, staring with dazed

eyes at the slicker and its mocking contents. A racking, horrible laugh

rattled from his dry lips. Then he went on back to the cabin, his brain

aching dully with milling thoughts.

Cotton Eye had taken the money. Cotton Eye was a thief as well as a

crooked card sharp. It was hard to take--after what he’d done fer Cotton

Eye.

“Well, the damn’ stuff is gone. Gone fer keeps. Too late now to send it

back with that confession ... Cotton Eye would be headed south by now

... south ... with five thousand dollars.”

Then a slow grin spread across the mouth of Buck Bell. He chuckled, then

laughed until the coffee boiled over and on to the stove.

“That’s shore one on me. Frettin’ and stewin’ around about that money.

Him playin’ possum with that leg. Diggin’ ’er up, when I rode off

yesterday. But how’d he know I had it? How’d he know where it was

buried? Well, I got all winter to figger ’er out.”

* * * * *

Days slipped into weeks. Weeks of white isolation. The hay was about

gone. No word from the ranch. And that eternal gray sky overhead like a

shroud.

Came that morning when Buck Bell looked out at the empty hay corral.

This was the end of the trail. All about the cabin the gaunt eyed cattle

walked aimlessly, bawling. Buck went back into the cabin and began

packing. When his grub was sacked and his bed rolled he went out to the

barn and hooked the team to his crude snow plow. He tied his saddle

horse to the off horse and loaded his bed and grub on the snow plow.

Then he scrawled a note and laid it on the rawhide covered table,

weighting it with a can of frozen tomatoes.

Closing the door of the log cabin, he picked up the lines and seated

himself on the snow plow. As the team got under way, he grinned back

over his shoulder.

“So long, cabin. Here goes nothin’.”

Behind him, bawling hungrily, trailed the cattle. Their dumb faith was

pinned to the man and his horses.

South into the breaks across the frozen river. The sun was a dim white

ball in a dead sky. The air was still and sharp. The snow plow creaked

and groaned.

“Come on, dogies!”

A gaunt scarecrow of a man, riding his crazy plow. A beard covered his

face up to the frost blackened cheekbones. His clothes were a patchwork

of blanket, cowhide, and buckskin with the hair on. His hair came to his

shoulders. Under the deerhide covering, his hands and feet were swollen

and stiff from frostbite.

“Sam Bass was born in Indiana; it was his native home.

And at the age of seventeen, young Sam begun to roam.”

The song blended crazily with the bawl of starving cattle, the creak of

his covered plow runners and the click of hoofs.

South into the sheltering badlands where the snow was deep but soft. The

plow cut through, clearing a ten foot path through the drifts. The

cattle packed the trail, crowding and riding one another to get to the

precious feed.

“Grass belly deep!” cried Buck, looking back. “Come on, you hungry

dogies! Git the wrinkles outa your paunches. Mebbe so it’s come

Christmas fer you.”

He unhooked the team at last and watered them at a hole cut in the ice.

He camped at the edge of the cleared bottomland and his pitch fire sent

its crimson shaft into the night. He had found feed for his cattle.

There was more to be had for the plowing. He slept that night with a

smile of tired happiness on his bearded, frost cracked lips.

In those days to come, Buck Bell found a measure of happiness and peace.

He labored untiringly, a man of rawhide. A bearded, frost blackened

scarecrow. And the haunting ache of that stolen money slipped into a

forgetfulness, buried by the work he was doing.

He cleared huge patches of grass. He rode back across the river and

trailed in more starving cattle to share his grass. Sometimes he came

within a mile of the cabin at Rocky Point but always he was too busy to

stop. Those short days were too brief to waste even a few minutes in

idle pastime. The snow was too deep to tire his horse in breaking

useless trail to the cabin to see whether any one had been there.

So he did not know that Horace had come and found that note on the

table.

Hay’s played out. I’m pullin’ out. If I don’t die off before

the chinook comes, I'll come in and give myself up. I taken

that money that night in town. Then I lost it. So the law kin

take it outa my hide. --BUCK BELL.

A frozen, wolf gnawed steer carcass lay near the cabin. Its ripped

paunch held no grass. Only willow sticks, some of them almost the

thickness of a man’s wrist.

* * * * *

This was the winter of ’86-’87, when the drift fences and cut coulees

held the hide and bones of a hundred thousand steers. When the mercury

hung below forty-five, and more than a few cowboys died for their

outfits. When cowmen stared out across the blizzard swept hills, dry

eyed, with aching lumps in their throats. Grim, silent, defeated.

The sun was a white ball inside its circle of gray, cold as the eye of a

corpse. Sun dogs followed its passing, across a sky that knew no warmth.

At night the patches of stars seemed frozen in a black agate sky.

And when the last of the hay was gone, the men sat about the bunkhouse

stove. And the strings of staggering, bawling cattle drifted on down the

wind to death.

At night the wolves and coyotes flung the death song toward the

glittering stars.

That was the winter of ’86-’87. The winter that broke the back of the

cow country.

South of the river, Buck Bell watched the last of the feed go. He had

lost track of the days. He did not know what month it was. But he knew

that the grass had played out and that the end of the trail lay just

ahead. His grub was gone and he was living on meat and beans. Each day

he felt of his teeth to test the coming symptoms of scurvy. His clothes

were a mass of patches. His eyes were swollen almost shut, the lids

scaled from frost, the eyeballs discolored by snow blindness. Only half

a dozen matches remained in his pocket. He could not remember the taste

of tobacco and coffee.

Half frozen, he lay in a knot under tarp and blankets, that night in

early spring when a wind roared down out of the canons with a droning,

rushing sound.

The scrub pines whispered; cattle got to their feet. Buck stirred a

little under the tarp, hardly awake. Then the wind cut down the river

and swept his forlorn camp. No man who has ever heard the voice of the

chinook wind can ever forget its whimper. Buck threw back the tarp and

the warm blast rushed down upon him.

A harsh, choking cry broke from his throat as he sat up in bed. His

arms, ragged, aching, frost seared, flung out in a wide gesture. His

face, bearded and scarred black, lifted. His eyes found the stars that

seemed close overhead in a warm sky. Terrible sobs shook him. Tears

streamed down from his aching eyes.

“God, oh, God!”

Over and over again.

“God!”

He could find no other word to fit into the prayer that sobbed and

rattled and laughed in his throat.

The weary horses felt the blessing of that chinook wind. The cattle

milled and bawled a restless chant. The melting snow in the tree

branches dripped with increasing cadence. A golden moon rode across the

sky toward the jagged skyline. The hard winter was over. The chinook had

come. Its passage through the pines sang the requiem of cattle and

horses and men that slept beneath the crusted drifts.

And when the coulees became rivers and the ridges lay bare, Buck Bell

trailed his straggling herd up the ridge and on to the open prairie.

“Git along, little dogies, git along!”

He sang in a cracked voice as his horse patiently followed the drags.

* * * * *

And so they found him that day in the Spring of ’87. Horace and the

little man with the white beard and puckered, sky blue eyes who owned

the Circle C. Horace and the Old Gent.

They did not know him. Their eyes were dim with the miracle that lay

before them. Cattle. Hundreds of cattle, grazing hungrily. And behind

them a snow blind man who was all hair and rags, who sang in a crazy

voice, the words of “Sam Bass.”

A phantom herd followed by a ghost. It was impossible to believe that so

many cattle could have lived, while so many thousands of others had

died. Buck’s herd filled the coulees and covered the ridges. The chain

harness rattled on the work team that was hooked to a bull hide which

held Buck’s bed and two young calves hog tied.

A dozen brands were represented in that gaunt herd. One of those calves

belonged to the Widow Brown’s Jersey milk cow. Its father was the prize

Circle Diamond bull that had strayed down from its Canadian range. Half

of Dick Powell’s herd was there.

“Sam Bass was born in Indiana...”

Between them, the Old Gent and Horace got Buck Bell to the ranch.

Somebody went for Doc Steele, fifty miles away. For Buck was blind and

one foot so badly frozen that three toes had to come off.

“He’ll see again in ten days,” said the doctor. “Let him sleep. Give him

warm food. Go slow on the whisky. He has a barb wire constitution and a

rawhide carcass.” He was a little puzzled at Buck’s delirious babbling.

“He’s been worrying about something.”

Horace and the Old Gent exchanged glances. The owner of the Circle C

thoughtfully stroked his whiskers and smiled down at the sleeping Buck

Bell. Then he handed the doctor the note that Horace had found on the

table at the deserted line camp at Rocky Point. Doc Steele knew cowboys.

He understood. He handed back the note and blew his nose like a trumpet.

The Old Gent fetched glasses and the bottle.

“Cotton Eye got here about New Year’s, Doc. He had five thousand dollars

and said he’d stole it. Wanted to plead guilty and take his medicine.

His story didn’t hold water. He’d been sitting in a poker game when the

money was stolen at the depot. Horace knew Buck was the thief because

the melting snow on Buck’s hat and clothes showed he’d been out in the

storm about the time that depot man was robbed. Cotton Eye finally

admitted he’d stolen the money from Buck. Buck had kept him awake

nights, talking about the robbery in his sleep like a man gone loco.

Buck saved Cotton Eye’s life and he wanted to return the favor.”

Doc Steele chuckled deep down in his muscular throat.

“Couple of sentimental old sage hens. It’s a damn’ shame, sir, that we

haven’t more of such outlaws in this world.”

He lifted his glass.

“Here’s to ’em.”

“May their breed never die out.”

When they had set down their glasses, Doc Steele looked quizzically at

the cowman.

“How is this thing going to be squared with the mining people?”

The sky blue eyes of the old cattleman twinkled. Doc Steele was somehow

reminded of the sun shining through summer rain.

“I bought the damn’ mine, Doc. Last fall. I don’t think that anything

more need be said about that fool holdup. Buck Bell saved what cattle I

have left. God and Buck Bell alone know how he managed. You should have

seen what I saw. The whole range spotted with dead critters. Like a

boneyard a hundred miles square. We’d rode all day across a cow country

graveyard. When I heard cattle bawling, I thought I was dreaming. That

herd trailing up out of the breaks. A man too weak to walk, riding

behind ’em, singing-- It was something, Doc, that a man won’t ever

forget.”

They filled their glasses and drank in silence. Then they tiptoed out

and Buck Bell slept on, a smile of peace on his frost cracked lips.

Outside, the chinook wind whispered its promise to the cow country.

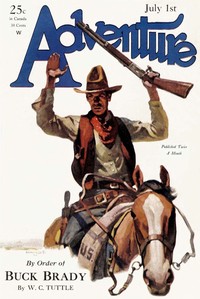

[Transcriber’s Note: This story appeared in the July 1, 1928 issue

of Adventure magazine.]

*** END OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK 73960 ***

Excerpt

A powerful story of the Montana cattletrails

and the Great Blizzard of ’86

Every stockman in the northwest recalls the hard winter of ’86-’87. It

broke most of them. One cattleman, spending his winter in the South,

wrote back to his ranch to inquire how his stuff was wintering. His line

rider took a pencil and drew the picture of a starving cow hung up in

the drifts. Under it he wrote:

Waiting for a chinook. The last of the five thousand.

The man who drew...

Read the Full Text

— End of The man who hated himself —

Book Information

- Title

- The man who hated himself

- Author(s)

- Coburn, Walt

- Language

- English

- Type

- Text

- Release Date

- July 4, 2024

- Word Count

- 8,280 words

- Library of Congress Classification

- PS

- Bookshelves

- Browsing: Culture/Civilization/Society, Browsing: Literature, Browsing: Fiction

- Rights

- Public domain in the USA.

Related Books

Famous stories from foreign countries

English

494h 26m read

The incredible slingshot bombs

by Williams, Robert Moore

English

96h 4m read

The eater of souls

by Kuttner, Henry

English

22h 19m read

Sun Dog loot

by Tuttle, W. C. (Wilbur C.)

English

769h 16m read

Henry goes prehistoric

by Tuttle, W. C. (Wilbur C.)

English

249h 1m read

Maehoe

by Leinster, Murray

English

115h 53m read