*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK 73793 ***

The LOST RACE

By Robert E. Howard

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Weird Tales January 1927.]

Cororuc glanced about him and hastened his pace. He was no coward, but

he did not like the place. Tall trees rose all about, their sullen

branches shutting out the sunlight. The dim trail led in and out among

them, sometimes skirting the edge of a ravine, where Cororuc could gaze

down at the tree-tops beneath. Occasionally, through a rift in the

forest, he could see away to the forbidding hills that hinted of the

ranges much farther to the west, that were the mountains of Cornwall.

In those mountains the bandit chief, Buruc the Cruel, was supposed to

lurk, to descend upon such victims as might pass that way. Cororuc

shifted his grip on his spear and quickened his step. His haste was

due not only to the menace of the outlaws, but also to the fact that

he wished once more to be in his native land. He had been on a secret

mission to the wild Cornish tribesmen: and though he had been more

or less successful, he was impatient to be out of their inhospitable

country. It had been a long, wearisome trip, and he still had nearly

the whole of Britain to traverse. He threw a glance of aversion about

him. He longed for the pleasant woodlands, with scampering deer, and

chirping birds, to which he was used. He longed for the tall white

cliff, where the blue sea lapped merrily. The forest through which he

was passing seemed uninhabited. There were no birds, no animals; nor

had he seen a sign of a human habitation.

His comrades still lingered at the savage court of the Cornish king,

enjoying his crude hospitality, in no hurry to be away. But Cororuc was

not content. So he had left them to follow at their leisure and had set

out alone.

Rather a fine figure of a man was Cororuc. Some six feet in height,

strongly though leanly built, he was, with gray eyes, a pure Briton but

not a pure Celt, his long yellow hair revealing, in him as in all his

race, a trace of Belgæ.

He was clad in skilfully dressed deerskin, for the Celts had not yet

perfected the coarse cloth which they made, and most of the race

preferred the hides of deer.

He was armed with a long bow of yew wood, made with no especial skill

but an efficient weapon; a long bronze broadsword, with a buckskin

sheath, a long bronze dagger and a small, round shield, rimmed with

a band of bronze and covered with tough buffalo hide. A crude bronze

helmet was on his head. Faint devices were painted in woad on his arms

and cheeks.

His beardless face was of the highest type of Briton, clear,

straightforward, the shrewd, practical determination of the Nordic

mingling with the reckless courage and dreamy artistry of the Celt.

So Cororuc trod the forest path, warily, ready to flee or fight, but

preferring to do neither just then.

The trail led away from the ravine, disappearing around a great tree.

And from the other side of the tree, Cororuc heard sounds of conflict.

Gliding warily forward, and wondering whether he should see some of the

elves and dwarfs that were reputed to haunt those woodlands, he peered

around the great tree.

A few feet from him he saw a strange tableau. Backed against another

tree stood a large wolf, at bay, blood trickling from gashes about his

shoulder; while before him, crouching for a spring, the warrior saw a

great panther. Cororuc wondered at the cause of the battle. Not often

the lords of the forest met in warfare. And he was puzzled by the

snarls of the great cat. Savage, blood-lusting, yet they held a strange

note of fear; and the beast seemed hesitant to spring in.

Just why Cororuc chose to take the part of the wolf, he himself

could not have said. Doubtless it was just the reckless chivalry of

the Celt of him, an admiration for the dauntless attitude of the

wolf against his far more powerful foe. Be that as it may, Cororuc,

characteristically forgetting his bow and taking the more reckless

course, drew his sword and leaped in front of the panther. But he had

no chance to use it. The panther, whose nerve appeared to be already

somewhat shaken, uttered a startled screech and disappeared among the

trees so quickly that Cororuc wondered if he had really seen a panther.

He turned to the wolf, wondering if it would leap upon him. It was

watching him, half crouching; slowly it stepped away from the tree, and

still watching him, backed away a few yards, then turned and made off

with a strange shambling gait. As the warrior watched it vanish into

the forest, an uncanny feeling came over him: he had seen many wolves,

he had hunted them and had been hunted by them, but he had never seen

such a wolf before.

He hesitated and then walked warily after the wolf, following the

tracks that were plainly defined in the soft loam. He did not hasten,

being merely content to follow the tracks. After a short distance, he

stopped short, the hairs on his neck seeming to bristle. _Only the

tracks of the hind feet showed: the wolf was walking erect._

He glanced about him. There was no sound; the forest was silent. He

felt an impulse to turn and put as much territory between him and the

mystery as possible, but his Celtic curiosity would not allow it. He

followed the trail. And then it ceased altogether. Beneath a great

tree the tracks vanished. Cororuc felt the cold sweat on his forehead.

What kind of place was that forest? Was he being led astray and eluded

by some inhuman, supernatural monster of the woodlands, who sought to

ensnare him? And Cororuc backed away, his sword lifted, his courage

not allowing him to run, but greatly desiring to do so. And so he came

again to the tree where he had first seen the wolf. The trail he had

followed led away from it in another direction and Cororuc took it up,

almost running in his haste to get out of the vicinity of a wolf who

walked on two legs and then vanished in the air.

* * * * *

The trail wound about more tediously than ever, appearing and

disappearing within a dozen feet, but it was well for Cororuc that it

did, for thus he heard the voices of the men coming up the path before

they saw him. He took to a tall tree that branched over the trail,

lying close to the great bole, along a wide-flung branch.

Three men were coming down the forest path.

One was a big, burly fellow, vastly over six feet in height, with a

long red beard and a great mop of red hair. In contrast, his eyes were

a beady black. He was dressed in deer-skins, and armed with a great

sword.

Of the two others, one was a lanky, villainous-looking scoundrel, with

only one eye, and the other was a small, wizened man, who squinted

hideously with both beady eyes.

Cororuc knew them, by descriptions the Cornishmen had made between

curses, and it was in his excitement to get a better view of the most

villainous murderer in Britain that he slipped from the tree branch and

plunged to the ground directly between them.

He was up on the instant, his sword out. He could expect no mercy; for

he knew that the red-haired man was Buruc the Cruel, the scourge of

Cornwall.

The bandit chief bellowed a foul curse and whipped out his great

sword. He avoided the Briton's furious thrust by a swift backward leap

and then the battle was on. Buruc rushed the warrior from the front,

striving to beat him down by sheer weight; while the lanky, one-eyed

villain slipped around, trying to get behind him. The smaller man had

retreated to the edge of the forest. The fine art of the fence was

unknown to those early swordsmen. It was hack, slash, stab, the full

weight of the arm behind each blow. The terrific blows crashing on his

shield beat Cororuc to the ground, and the lanky, one-eyed villain

rushed in to finish him. Cororuc spun about without rising, cut the

bandit's legs from under him and stabbed him as he fell, then threw

himself to one side and to his feet, in time to avoid Buruc's sword.

Again, driving his shield up to catch the bandit's sword in midair, he

deflected it and whirled his own with all his power. Buruc's head flew

from his shoulders.

Then Cororuc, turning, saw the wizened bandit scurry into the forest.

He raced after him, but the fellow had disappeared among the trees.

Knowing the uselessness of attempting to pursue him, Cororuc turned

and raced down the trail. He did not know if there were more bandits

in that direction, but he did know that if he expected to get out of

the forest at all, he would have to do it swiftly. Without doubt the

villain who had escaped would have all the other bandits out, and soon

they would be beating the woodlands for him.

After running for some distance down the path and seeing no sign of any

enemy, he stopped and climbed into the topmost branches of a tall tree,

that towered above its fellows.

On all sides he seemed surrounded by a leafy ocean. To the west he

could see the hills he had avoided. To the north, far in the distance

other hills rose; to the south the forest ran, an unbroken sea. But

to the east, far away, he could barely see the line that marked the

thinning out of the forest into the fertile plains. Miles and miles

away, he knew not how many, but it meant more pleasant travel, villages

of men, people of his own race. He was surprized that he was able to

see that far, but the tree in which he stood was a giant of its kind.

Before he started to descend, he glanced about nearer at hand. He could

trace the faintly marked line of the trail he had been following,

running away into the east; and could make out other trails leading

into it, or away from it. Then a glint caught his eye. He fixed his

gaze on a glade some distance down the trail and saw, presently, a

party of men enter and vanish. Here and there, on every trail, he

caught glances of the glint of accouterments, the waving of foliage.

So the squinting villain had already roused the bandits. They were all

around him; he was virtually surrounded.

A faintly heard burst of savage yells, from back up the trail, startled

him. So, they had already thrown a cordon about the place of the fight

and had found him gone. Had he not fled swiftly, he would have been

caught. He was outside the cordon, but the bandits were all about him.

Swiftly he slipped from the tree and glided into the forest.

Then began the most exciting hunt Cororuc had ever engaged in; for he

was the hunted and men were the hunters. Gliding, slipping from bush

to bush and from tree to tree, now running swiftly, now crouching in a

covert, Cororuc fled, ever eastward; not daring to turn back lest he be

driven farther back into the forest. At times he was forced to turn his

course; in fact, he very seldom fled in a straight course, yet always

he managed to work farther eastward.

Sometimes he crouched in bushes or lay along some leafy branch, and

saw bandits pass so close to him that he could have touched them. Once

or twice they sighted him and he fled, bounding over logs and bushes,

darting in and out among the trees; and always he eluded them.

It was in one of those headlong flights that he noticed he had entered

a defile of small hills, of which he had been unaware, and looking back

over his shoulder, saw that his pursuers had halted, within full sight.

Without pausing to ruminate on so strange a thing, he darted around a

great boulder, felt a vine or something catch his foot, and was thrown

headlong. Simultaneously something struck the youth's head, knocking

him senseless.

* * * * *

When Cororuc recovered his senses, he found that he was bound, hand and

foot. He was being borne along, over rough ground. He looked about him.

Men carried him on their shoulders, but such men as he had never seen

before. Scarce above four feet stood the tallest, and they were small

of build and very dark of complexion. Their eyes were black; and most

of them went stooped forward, as if from a lifetime spent in crouching

and hiding; peering furtively on all sides. They were armed with

small bows, arrows, spears and daggers, all pointed, not with crudely

worked bronze but with flint and obsidian, of the finest workmanship.

They were dressed in finely dressed hides of rabbits and other small

animals, and a kind of coarse cloth; and many were tattooed from head

to foot in ocher and woad. There were perhaps twenty in all. What sort

of men were they? Cororuc had never seen the like.

They were going down a ravine, on both sides of which steep cliffs

rose. Presently they seemed to come to a blank wall, where the ravine

appeared to come to an abrupt stop. Here, at a word from one who seemed

to be in command, they set the Briton down, and seizing hold of a large

boulder, drew it to one side. A small cavern was exposed, seeming to

vanish away into the earth; then the strange men picked up the Briton

and moved forward.

Cororuc's hair bristled at thought of being borne into that

forbidding-looking cave. What manner of men were they? In all Britain

and Alba, in Cornwall or Ireland, Cororuc had never seen such men.

Small dwarfish men, who dwelt in the earth. Cold sweat broke out on the

youth's forehead. Surely they were the malevolent dwarfs of whom the

Cornish people had spoken, who dwelt in their caverns by day, and by

night sallied forth to steal and burn dwellings, even slaying if the

opportunity arose! You will hear of them, even today, if you journey in

Cornwall.

The men, or elves, if such they were, bore him into the cavern, others

entering and drawing the boulder back into place. For a moment all was

darkness, and then torches began to glow, away off. And at a shout they

moved on. Other men of the caves came forward, with the torches.

Cororuc looked about him. The torches shed a vague glow over the

scene. Sometimes one, sometimes another wall of the cave showed for

an instant, and the Briton was vaguely aware that they were covered

with paintings, crudely done, yet with a certain skill his own race

could not equal. But always the roof remained unseen. Cororuc knew that

the seemingly small cavern had merged into a cave of surprizing size.

Through the vague light of the torches the strange people moved, came

and went, silently, like shadows of the dim past.

He felt the cords or thongs that bound his feet loosened. He was lifted

upright.

"Walk straight ahead," said a voice, speaking the language of his own

race, and he felt a spearpoint touch the back of his neck.

And straight ahead he walked, feeling his sandals scrape on the

stone floor of the cave, until they came to a place where the floor

tilted upward. The pitch was steep and the stone was so slippery that

Cororuc could not have climbed it alone. But his captors pushed him,

and pulled him, and he saw that long, strong vines were strung from

somewhere at the top.

Those the strange men seized, and bracing their feet against the

slippery ascent, went up swiftly. When their feet found level surface

again, the cave made a turn, and Cororuc blundered out into a firelit

scene that made him gasp.

The cave debouched into a cavern so vast as to be almost incredible.

The mighty walls swept up into a great arched roof that vanished in the

darkness. A level floor lay between, and through it flowed a river; an

underground river. From under one wall it flowed to vanish silently

under the other. An arched stone bridge, seemingly of natural make,

spanned the current.

All around the walls of the great cavern, which was roughly circular,

were smaller caves, and before each glowed a fire. Higher up were other

caves, regularly arranged, tier on tier. Surely human men could not

have built such a city.

In and out among the caves, on the level floor of the main cavern,

people were going about what seemed daily tasks. Men were talking

together and mending weapons, some were fishing from the river;

women were replenishing fires, preparing garments; and altogether it

might have been any other village in Britain, to judge from their

occupations. But it all struck Cororuc as extremely unreal; the strange

place, the small, silent people, going about their tasks, the river

flowing silently through it all.

Then they became aware of the prisoner and flocked about him. There was

none of the shouting, abuse and indignities, such as savages usually

heap on their captives, as the small men drew about Cororuc, silently

eyeing him with malevolent, wolfish stares. The warrior shuddered, in

spite of himself.

But his captors pushed through the throng, driving the Briton before

them. Close to the bank of the river, they stopped and drew away from

around him.

* * * * *

Two great fires leaped and flickered in front of him and there was

something between them. He focused his gaze and presently made out the

object. A high stone seat, like a throne; and in it seated an aged man,

with a long white beard, silent, motionless, but with black eyes that

gleamed like a wolf's.

The ancient was clothed in some kind of a single, flowing garment. One

clawlike hand rested on the seat near him, skinny, crooked fingers,

with talons like a hawk's. The other hand was hidden among his garments.

The firelight danced and flickered; now the old man stood out clearly,

his hooked, beaklike nose and long beard thrown into bold relief; now

he seemed to recede until he was invisible to the gaze of the Briton,

except for his glittering eyes.

"Speak, Briton!" The words came suddenly, strong, clear, without a hint

of age. "Speak, what would ye say?"

Cororuc, taken aback, stammered and said, "Why, why--what manner of

people are you? Why have you taken me prisoner? Are you elves?"

"We are Picts," was the stern reply.

"Picts!" Cororuc had heard tales of those ancient people from the

Gaelic Britons; some said that they still lurked in the hill of

Siluria, but----

"I have fought Picts in Caledonia," the Briton protested; "they are

short but massive and misshapen; not at all like you!"

"They are not true Picts," came the stern retort. "Look about you,

Briton," with a wave of an arm, "you see the remnants of a vanishing

race; a race that once ruled Britain from sea to sea."

The Briton stared, bewildered.

"Harken, Briton," the voice continued; "harken, barbarian, while I tell

to you the tale of the lost race."

The firelight flickered and danced, throwing vague reflections on the

towering walls and on the rushing, silent current.

The ancient's voice echoed through the mighty cavern.

"Our people came from the south. Over the islands, over the Inland

Sea. Over the snow-topped mountains, where some remained, to stay

any enemies who might follow. Down into the fertile plains we came.

Over all the land we spread. We became wealthy and prosperous. Then

two kings arose in the land, and he who conquered, drove out the

conquered. So many of us made boats and set sail for the far-off cliffs

that gleamed white in the sunlight. We found a fair land with fertile

plains. We found a race of red-haired barbarians, who dwelt in caves.

Mighty giants, of great bodies and small minds.

"We built our huts of wattle. We tilled the soil. We cleared the

forest. We drove the red-haired giants back into the forest. Farther we

drove them back until at last they fled to the mountains of the west

and the mountains of the north. We were rich. We were prosperous.

"Then," and his voice thrilled with rage and hate, until it seemed to

reverberate through the cavern, "then the Celts came. From the isles of

the west, in their rude coracles they came. In the west they landed,

but they were not satisfied with the west. They marched eastward and

seized the fertile plains. We fought. They were stronger. They were

fierce fighters and they were armed with weapons of bronze, whereas we

had only weapons of flint.

"We were driven out. They enslaved us. They drove us into the forest.

Some of us fled into the mountains of the west. Many fled into the

mountains of the north. There they mingled with the red-haired giants

we drove out so long ago, and became a race of monstrous dwarfs, losing

all the arts of peace and gaining only the ability to fight.

"But some of us swore that we would never leave the land we had fought

for. But the Celts pressed us. There were many, and more came. So we

took to caverns, to ravines, to caves. We, who had always dwelt in huts

that let in much light, who had always tilled the soil, we learned to

dwell like beasts, in caves where no sunlight ever entered. Caves we

found, of which this is the greatest; caves we made.

"You, Briton," the voice became a shriek and a long arm was

outstretched in accusation, "you and your race! You have made a free,

prosperous nation into a race of earth-rats! We who never fled, who

dwelt in the air and the sunlight close by the sea where traders came,

we must flee like hunted beasts and burrow like moles! But at night!

Ah, then for our vengeance! Then we slip from our hiding places, from

our ravines and our caves, with torch and dagger! Look, Briton!"

And following the gesture, Cororuc saw a rounded post of some kind of

very hard wood, set in a niche in the stone floor, close to the bank.

The floor about the niche was charred as if by old fires.

Cororuc stared, uncomprehending. Indeed, he understood little of what

had passed. That these people were even human, he was not at all

certain. He had heard so much of them as "little people." Tales of

their doings, their hatred of the race of man, and their maliciousness

flocked back to him. Little he knew that he was gazing on one of the

mysteries of the ages. That the tales which the ancient Gaels told of

the Picts, already warped, would become even more warped from age to

age, to result in tales of elves, dwarfs, trolls and fairies, at first

accepted and then rejected, entire, by the race of men, just as the

Neandertal monsters resulted in tales of goblins and ogres. But of that

Cororuc neither knew nor cared, and the ancient was speaking again.

"There, there, Briton," exulted he, pointing to the post, "there you

shall pay! A scant payment for the debt your race owes mine, but to the

fullest of your extent."

The old man's exultation would have been fiendish, except for a certain

high purpose in his face. He was sincere. He believed that he was only

taking just vengeance; and he seemed like some great patriot for a

mighty, lost cause.

"But I am a Briton!" stammered Cororuc. "It was not my people who drove

your race into exile! They were Gaels, from Ireland. I am a Briton and

my race came from Gallia only a hundred years ago. We conquered the

Gaels and drove them into Erin, Wales and Caledonia, even as they drove

your race."

"No matter!" The ancient chief was on his feet. "A Celt is a Celt.

Briton, or Gael, it makes no difference. Had it not been Gael, it would

have been Briton. Every Celt who falls into our hands must pay, be it

warrior or woman, babe or king. Seize him and bind him to the post."

In an instant Cororuc was bound to the post, and he saw, with horror,

the Picts piling firewood about his feet.

"And when you are sufficiently burned, Briton," said the ancient, "this

dagger that has drunk the blood of an hundred Britons, shall quench its

thirst in yours."

"But never have I harmed a Pict!" Cororuc gasped, struggling with his

bonds.

"You pay, not for what you did, but for what your race has done,"

answered the ancient sternly. "Well do I remember the deeds of

the Celts when first they landed on Britain--the shrieks of the

slaughtered, the screams of ravished girls, the smokes of burning

villages, the plundering."

Cororuc felt his short neck-hairs bristle. When first the Celts landed

on Britain! That was over five hundred years ago!

And his Celtic curiosity would not let him keep still, even at the

stake with the Picts preparing to light firewood piled about him.

"You could not remember that. That was ages ago."

The ancient looked at him somberly. "And I am age-old. In my youth I

was a witch-finder, and an old woman witch cursed me as she writhed at

the stake. She said I should live until the last child of the Pictish

race had passed. That I should see the once mighty nation go down into

oblivion and then--and only then--should I follow it. For she put upon

me the curse of life everlasting."

Then his voice rose until it filled the cavern, "But the curse was

nothing. Words can do no harm, can do nothing, to a man. I live. An

hundred generations have I seen come and go, and yet another hundred.

What is time? The sun rises and sets, and another day has passed into

oblivion. Men watch the sun and set their lives by it. They league

themselves on every hand with time. They count the minutes that race

them into eternity. Man outlived the centuries ere he began to reckon

time. Time is man-made. Eternity is the work of the gods. In this

cavern there is no such thing as time. There are no stars, no sun.

Without is time; within is eternity. We count not time. Nothing marks

the speeding of the hours. The youths go forth. They see the sun, the

stars. They reckon time. And they pass. I was a young man when I

entered this cavern. I have never left it. As you reckon time, I may

have dwelt here a thousand years; or an hour. When not banded by time,

the soul, the mind, call it what you will, can conquer the body. And

the wise men of the race, in my youth, knew more than the outer world

will ever learn. When I feel that my body begins to weaken, I take the

magic draft, that is known only to me, of all the world. It does not

give immortality; that is the work of the mind alone; but it rebuilds

the body. The race of Picts vanish; they fade like the snow on the

mountain. And when the last is gone, this dagger shall free me from the

world." Then in a swift change of tone, "Light the fagots!"

* * * * *

Cororuc's mind was fairly reeling. He did not in the least understand

what he had just heard. He was positive that he was going mad; and what

he saw the next minute assured him of it.

Through the throng came a wolf; and he knew that it was the wolf whom

he had rescued from the panther close by the ravine in the forest!

Strange, how long ago and far away that seemed! Yes, it was the same

wolf. That same strange, shambling gait. Then the thing stood erect and

raised its front feet to its head. What nameless horror was that?

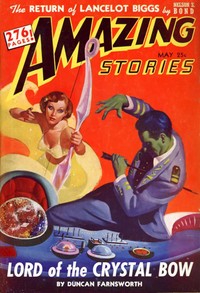

[Illustration: "Then the thing stood erect and raised its front feet to

its head. What nameless horror was that?"]

Then the wolf's head fell back, disclosing a man's face. The face of

a Pict; one of the first "werewolves." The man stepped out of the

wolfskin and strode forward, calling something. A Pict just starting

to light the wood about the Briton's feet drew back the torch and

hesitated.

The wolf-Pict stepped forward and began to speak to the chief, using

Celtic, evidently for the prisoner's benefit. (Cororuc was surprized to

hear so many speak his language, not reflecting upon its comparative

simplicity, and the ability of the Picts.)

"What is this?" asked the Pict who had played wolf. "A man is to be

burned who should not be!"

"How?" exclaimed the old man fiercely, clutching his long beard. "Who

are you to go against a custom of age-old antiquity?"

"I met a panther," answered the other, "and this Briton risked his life

to save mine. Shall a Pict show ingratitude?"

And as the ancient hesitated, evidently pulled one way by his fanatical

lust for revenge, and the other by his equally fierce racial pride,

the Pict burst into a wild flight of oration, carried on in his own

language. At last the ancient chief nodded.

"A Pict ever paid his debts," said he with impressive grandeur. "Never

a Pict forgets. Unbind him. No Celt shall ever say that a Pict showed

ingratitude."

Cororuc was released, and as, like a man in a daze, he tried to stammer

his thanks, the chief waved them aside.

"A Pict never forgets a foe, ever remembers a friendly deed," he

replied.

"Come," murmured his Pictish friend, tugging at the Celt's arm.

He led the way into a cave leading away from the main cavern. As they

went, Cororuc looked back, to see the ancient chief seated upon his

stone throne, his eyes gleaming as he seemed to gaze back through the

lost glories of the ages; on each hand the fires leaped and flickered.

A figure of grandeur, the king of a lost race.

On and on Cororuc's guide led him. And at last they emerged and the

Briton saw the starlit sky above him.

"In that way is a village of your tribesmen," said the Pict, pointing,

"where you will find a welcome until you wish to take up your journey

anew."

And he pressed gifts on the Celt; gifts of garments of cloth and finely

worked deerskin, beaded belts, a fine horn bow with arrows skilfully

tipped with obsidian. Gifts of food. His own weapons were returned to

him.

"But an instant," said the Briton, as the Pict turned to go. "I

followed your tracks in the forest. They vanished." There was a

question in his voice.

The Pict laughed softly, "I leaped into the branches of the tree. Had

you looked up, you would have seen me. If ever you wish a friend, you

will ever find one in Berula, chief among the Alban Picts."

He turned and vanished. And Cororuc strode through the moonlight toward

the Celtic village.

*** END OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK 73793 ***

The lost race

Download Formats:

Excerpt

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Weird Tales January 1927.]

Cororuc glanced about him and hastened his pace. He was no coward, but

he did not like the place. Tall trees rose all about, their sullen

branches shutting out the sunlight. The dim trail led in and out among

them, sometimes skirting the edge of a ravine, where Cororuc could gaze

down at the tree-tops beneath. Occasionally, through a rift in the

forest, he could see away to the forbidding...

Read the Full Text

— End of The lost race —

Book Information

- Title

- The lost race

- Author(s)

- Howard, Robert E. (Robert Ervin)

- Language

- English

- Type

- Text

- Release Date

- June 8, 2024

- Word Count

- 5,291 words

- Library of Congress Classification

- PS

- Bookshelves

- Browsing: Literature, Browsing: Science-Fiction & Fantasy, Browsing: Fiction

- Rights

- Public domain in the USA.

Related Books

Three little Trippertrots

by Garis, Howard Roger

English

630h 28m read

Famous stories from foreign countries

English

494h 26m read

The incredible slingshot bombs

by Williams, Robert Moore

English

96h 4m read

The eater of souls

by Kuttner, Henry

English

22h 19m read

The fulfilment

by Allonby, Edith

English

1721h 41m read

Dragon moon

by Kuttner, Henry

English

219h 49m read