The Project Gutenberg eBook of The boy's book of battle-lyrics, by

Thomas English

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and

most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms

of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at

www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you

will have to check the laws of the country where you are located before

using this eBook.

Title: The boy's book of battle-lyrics

a collection of verses illustrating some notable events in the

history of the United States of America, from the colonial

period to the outbreak of the sectional war

Author: Thomas English

Release Date: March 31, 2023 [eBook #70415]

Language: English

Produced by: Bob Taylor, Brian Coe and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This book was

produced from images made available by the HathiTrust

Digital Library.)

*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE BOY'S BOOK OF

BATTLE-LYRICS ***

Transcriber’s Note

Italic text displayed as: _italic_

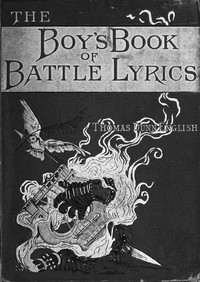

[Illustration: “—ON OUR CHIEFTAIN SPEEDED, RALLIED QUICK THE FLEEING

FORCES.”

[p. 105

]

THE BOY’S BOOK

OF

BATTLE-LYRICS

A COLLECTION OF VERSES ILLUSTRATING SOME NOTABLE EVENTS IN THE

HISTORY OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, FROM THE COLONIAL

PERIOD TO THE OUTBREAK OF THE SECTIONAL WAR

BY

THOS. DUNN ENGLISH, M.D., LL.D.

_WITH HISTORICAL NOTES

AND NUMEROUS ENGRAVINGS OF PERSONS, SCENES, AND PLACES_

NEW YORK

HARPER & BROTHERS, FRANKLIN SQUARE

1885

Copyright, 1885, by HARPER & BROTHERS.

_All rights reserved._

TO

ADOLPH SCHALK, ESQ.

AS A RECOGNITION OF MANY YEARS OF UNBROKEN FRIENDSHIP, AND AS A TOKEN

OF ESTEEM FOR HIS MANLINESS AND WORTH

THIS VOLUME IS INSCRIBED BY

THE AUTHOR

PREFACE.

During the last twenty-five years my work in verse has been mainly

confined to illustrating the history of the United States, with

occasional studies of local life and character. Of this, judging

by notices of the press, and their appearance in compilations of

a patriotic or martial nature, the metrical narratives of battles

seem to have been most approved; and it occurred to me that a volume

embracing my productions in that line of literary labor might meet

with popular favor. My first intention was to take up every notable

event, so that the book might be a complete metrical history, and I

prepared partly the matter for the purpose, including the capture of

the _Serapis_ and the achievements of _Old Ironsides_. But I found

the volume would be inconveniently large, and I abandoned my plan

reluctantly.

The historical sketches prefixed in the proper places will be found

full, unless the details are faithfully given in the text, when the

introductions are purposely made meagre. In either case they will

be found to be accurate, the verses being, as I have styled them,

“metrical narratives” rather than poems. In that form, I trust,

they more readily impress on the mind of the reader a sense of the

patriotism and courage of our forefathers, and give a notion of the

nature of the struggle by which these States emerged from a dependent

condition to take high rank among the peoples of the world. The story

of each event being told in the first person, the style and language

are intentionally marked by the peculiarities of the imaginary

narrator. And in this connection it will be observed that, because

of the nearness of the conflict, the battles of the late sectional

war have been avoided, and the two incidents of that period touched

on at the close are personal, and not likely to offend even the most

sensitive.

T. D. E.

NEWARK, N. J., _July 30, 1885_.

CONTENTS.

PAGE

PREFACE vii

_De Soto’s Expedition_ 1

THE FALL OF MAUBILA 2

_Bacon’s Rebellion_ 12

THE BURNING OF JAMESTOWN 13

_The Deerfield Massacre_ 16

THE SACK OF DEERFIELD 17

_The Lewises_ 24

THE FIGHT OF JOHN LEWIS 24

_The First Blood Drawn_ 31

THE FIGHT AT LEXINGTON 33

_Bombardment of Fort Sullivan_ 40

SULLIVAN’S ISLAND 41

_A Turn of the Tide_ 53

THE SURPRISE AT TRENTON 54

_Following the Operations at Trenton_ 61

ASSUNPINK AND PRINCETON 63

_Donald M’Donald_ 67

COLONEL HARPER’S CHARGE 67

_Oriskany_ 70

THE FIGHT AT ORISKANY 71

_Baum’s Expedition_ 83

THE BATTLE OF BENNINGTON 85

_The Capture of Burgoyne_ 90

ARNOLD AT STILLWATER 91

_Siege of Fort Henry_ 95

BETTY ZANE 96

_Operations at Monmouth_ 100

THE BATTLE OF MONMOUTH 103

_John Berry, the Loyalist_ 108

JACK, THE REGULAR 108

_Tarleton’s Defeat_ 112

THE BATTLE OF THE COWPENS 113

_The Affair of Cherry Valley_ 118

DEATH OF WALTER BUTLER 119

_The Fight of the Mountaineers_ 129

THE BATTLE OF KING’S MOUNTAIN 131

_Mrs. Merrill’s Defence_ 139

THE LONG-KNIFE SQUAW 139

_The Last Battle of the War_ 144

THE BATTLE OF NEW ORLEANS 149

_El Molino del Rey_ 156

BATTLE OF THE KING’S MILL 156

_A Tale of the War_ 160

THE FENCING-MASTER 160

_An Ambuscade_ 164

THE CHARGE BY THE FORD 164

_A New Folk-song_ 166

FLAG OF THE RAINBOW 166

ILLUSTRATIONS.

PAGE

“—ON OUR CHIEFTAIN SPEEDED, RALLIED QUICK }

THE FLEEING FORCES” } _Frontispiece_

HERNANDO DE SOTO 1

JAMESTOWN AS IT IS 12

ELEAZER WILLIAMS 16

“HUGE HE WAS, AND BRAVE AND BRAWNY, BUT I MET THE SLAYER TAWNY” 19

“FOR WHILE THEY THE HOUSE WERE HOLDING, BALLS THE WIVES WERE

QUICKLY MOULDING” 21

CLARK’S HOUSE, LEXINGTON 31

SAMUEL ADAMS 31

THE LEXINGTON MASSACRE 32

JOHN HANCOCK 32

FIGHT AT THE BRIDGE 33

BATTLE-GROUND AT CONCORD 35

MERIAM’S CORNER, ON THE LEXINGTON ROAD 36

HALT OF TROOPS NEAR ELISHA JONES’S HOUSE 36

THE PROVINCIALS ON PUNKATASSET 37

MONUMENT AT CONCORD 39

WILLIAM MOULTRIE 40

PLAN OF FORT ON SULLIVAN’S ISLAND 40

SOUTH CAROLINA FLAG 40

SULLIVAN’S ISLAND AND THE BRITISH FLEET AT THE TIME OF THE ATTACK 40

SIR HENRY CLINTON 42

SIR PETER PARKER 46

MOULTRIE MONUMENT, WITH JASPER’S STATUE 49

CHARLESTON IN 1780 51

TRENTON—1777 53

RAHL’S HEAD-QUARTERS 54

BATTLE OF TRENTON 55

SUBSEQUENT OPERATIONS 61

FRIENDS’ MEETING-HOUSE 62

VIEW OF THE BATTLE-GROUND NEAR PRINCETON 62

BATTLE OF PRINCETON 66

THE BATTLE-GROUND OF ORISKANY 70

PETER GANSEVOORT 70

GENERAL HERKIMER’S RESIDENCE 71

THE SITE OF OLD FORT SCHUYLER 72

GENERAL HERKIMER DIRECTING THE BATTLE 78

MARINUS WILLETT 81

MAP OF BENNINGTON HEIGHTS 83

VAN SCHAIK’S MILL 84

JOHN STARK 84

THE BATTLE-GROUND OF BENNINGTON 89

LIEUTENANT-GENERAL BURGOYNE 90

HORATIO GATES 90

BENEDICT ARNOLD 91

“FIVE TIMES WE CAPTURED THEIR CANNON, AND FIVE TIMES THEY TOOK

THEM AGAIN” 92

“FIRING ONE PARTHIAN VOLLEY” 94

GEORGE ROGERS CLARKE 95

PLAN OF THE BATTLE 100

LAFAYETTE IN 1777 101

GENERAL WAYNE 101

HENRY KNOX 102

FREEHOLD MEETING-HOUSE 102

BATTLE-GROUND AT MONMOUTH 103

WASHINGTON REBUKING LEE 105

MOLLY PITCHER 107

BANASTRE TARLETON 112

DANIEL MORGAN 112

WILLIAM WASHINGTON 114

JOHN E. HOWARD 116

JOSEPH BRANT 118

DISTANT VIEW OF CHERRY VALLEY 119

COLONEL ISAAC SHELBY 129

KING’S MOUNTAIN BATTLE-GROUND 130

ANDREW JACKSON 144

VILLERÉ’S MANSION 145

“THE HERMITAGE,” JACKSON’S RESIDENCE, IN 1861 146

JACKSON’S TOMB 147

PLAIN OF CHALMETTE.—BATTLE-GROUND 148

JOHN COFFEE 148

STATUE OF JACKSON IN FRONT OF THE CATHEDRAL 149

THE LAST CHARGE 158

THE BOY’S

BOOK OF BATTLE LYRICS.

_DE SOTO’S EXPEDITION._

Hernando de Soto was of good Spanish family, and started early

upon a career of adventure. He was with Francisco Pizarro, and

took a prominent part in the conquest of Peru. Some account of his

actions while with the Pizarros will be found in Helps’s “Spanish

Conquest in America.” He particularly distinguished himself in

the battle which resulted in the conquest of Cuzco, and desired

to be the lieutenant of Almagro in the invasion of Chili; but in

this he was disappointed. Returning to Spain with much wealth, he

married into the Bobadilla family, and became a favorite with the

king. Here he conceived the notion of conquering Florida, which

he believed to abound in gold and precious stones. Offering to do

this at his own expense, the king gave him permission, and at the

same time appointed him governor of Cuba. De Soto set sail from

Spain in April, 1538, but remained in Cuba some time fitting out

his expedition, which did not arrive at Florida until the following

year, when it landed at Tampa Bay. His force consisted of twelve

hundred men, with four hundred horses, and he took with him a

number of domestic animals. In quest of gold, he penetrated the

territory now known as the States of Alabama, Georgia, Tennessee,

and Mississippi, finally striking the Mississippi River, which he

called the Rio Grande, at or near the Lower Chickasaw Bluffs. He

found the inhabitants to be quite unlike the Peruvians. He met

with a fierce resistance from the natives, and by severe hardships

and bloody conflicts found his army very much reduced in numbers.

In 1542 De Soto died of a fever. To prevent the mutilation of his

body, it was enclosed in a coffin hollowed from the trunk of a

tree, and sunk at midnight in the great river. The command then

devolved on Moscoso, who escaped with his comrades by way of the

river, and reached Mexico in a miserable condition.

[Illustration: HERNANDO DE SOTO.]

It was during this raid, on the 18th of October, 1539, that the

battle with the Mobilians was fought. The incidents, so far as

they have been gathered from all sources, are faithfully given in

the ballad, with one exception. The speech of Tuscaloosa was in

the shape of a message, and was delivered by one of his men after

the chief had escaped and found refuge in his “palace,” which was

probably a hut more commodious than the others in the town. The

Spaniards, in spite of their superiority of weapons, had much the

worst of the affair at one time, and might have been disastrously

defeated but for the opportune arrival of Moscoso with the reserve

of four hundred fresh men. After that the battle changed to a mere

massacre.

The “singing women” described in the text must have been

picked Amazons, for the women in general, and children, had

been previously sent to a place of refuge by the Mobilians in

anticipation of a fight. The slaughter of the poorly armed natives

was very great, but the invaders suffered severely. Not only were

eighty-two killed, including the nephew and nephew-in-law of the

Adelantado (as De Soto was styled), but none of the Spaniards

escaped severe wounds. To add to their sufferings, the medicines

and surgical appliances, having been placed in the town previous to

the breaking out of the conflict, were burned, and all the surgeons

but one were killed. De Soto himself received an arrow in his

thigh. The missile was not extracted until after the battle, and he

was forced to continue the fight standing in his stirrups.

The place of the battle is supposed to be what is now known as

Choctaw Bluff, in Clarke County, Alabama.

_THE FALL OF MAUBILA._

Hearken the stirring story

The soldier has to tell,

Of fierce and bloody battle,

Contested long and well,

Ere walled Maubila, stoutly held,

Before our forces fell.

Now many years have circled

Since that October day,

When proudly to Maubila

De Soto took his way,

With men-at-arms and cavaliers

In terrible array.

Oh, never sight more goodly

In any land was seen;

And never better soldiers

Than those he led have been,

More prompt to handle arquebus,

Or wield their sabres keen.

The sun was at meridian,

His hottest rays fell down

Alike on soldier’s corselet

And on the friar’s gown;

The breeze was hushed as on we rode

Right proudly to the town.

First came the bold De Soto,

In all his manly pride,

The gallant Don Diego,

His nephew, by his side;

A yard behind Juan Ortiz rode,

Interpreter and guide.

Baltasar de Gallegos,

Impetuous, fierce, and hot;

Francisco de Figarro,

Since by an arrow shot;

And slender Juan de Guzman, who

In battle faltered not.

Luis Bravo de Xeres,

That gallant cavalier;

Alonzo de Cormono,

Whose spirit knew no fear;

The Marquis of Astorga, and

Vasquez, the cannoneer.

Andres de Vasconcellos,

Juan Coles, young and fair,

Roma de Cardenoso,

Him of the yellow hair—

Rode gallant in their bravery,

Straight to the public square.

And there, in sombre garments,

Were monks of Cuba four,

Fray Juan de Gallegos,

And other priests a score,

Who sacramental bread and wine

And holy relics bore.

And next eight hundred soldiers

In closest order come,

Some with Biscayan lances,

With arquebuses some,

Timing their tread to martial notes

Of trump and fife and drum.

Loud sang the gay Mobilians,

Light danced their daughters brown;

Sweet sounded pleasant music

Through all the swarming town;

But ’mid the joy one sullen brow

Was lowering with a frown.

The haughty Tuscaloosa,

The sovereign of the land,

With moody face, and thoughtful,

Rode at our chief’s right hand,

And cast from time to time a glance

Of hatred at the band.

And when that gay procession

Made halt to take a rest,

And eagerly the people

To see the strangers prest,

The frowning King, in wrathful tones,

De Soto thus addressed:

“To bonds and to dishonor

By faithless friends trepanned,

For days beside you, Spaniard,

The ruler of the land

Has ridden as a prisoner,

Subject to your command.

“He was not born the fetters

Of baser men to wear,

And tells you this, De Soto,

Hard though it be to bear—

Let those beware the panther’s rage

Who follow to his lair.

“Back to your isle of Cuba!

Slink to your den again,

And tell your robber sovereign,

The mighty lord of Spain,

Whoso would strive this land to win

Shall find his efforts vain.

“And, save it be your purpose

Within my realm to die,

Let not your forces linger

Our deadly anger nigh,

Lest food for vultures and for wolves

Your mangled forms should lie.”

Then, spurning courtly offers,

He left our chieftain’s side,

And crossing the enclosure

With quick and lengthened stride,

He passed within his palace gates,

And there our wrath defied.

Now came up Charamilla,

Who led our troop of spies,

And said unto our captain,

With tones that showed surprise,

“A mighty force within the town,

In wait to crush us, lies.

“The babes and elder women

Were sent at break of day

Into the forest yonder,

Five leagues or more away;

While in yon huts ten thousand men

Wait eager for the fray.”

“What say ye now, my comrades?”

De Soto asked his men;

“Shall we, before these traitors,

Go backward, baffled, then;

Or, sword in hand, attack the foe

Who crouches in his den?”

Before their loud responses

Had died upon the ear,

A savage stood before them,

Who said, in accents clear,

“Ho! robbers base and coward thieves!

Assassin Spaniards, hear!

“No longer shall our sovereign,

Born noble, great, and free,

Be led beside your master,

A shameful sight to see,

While weapons here to strike you down,

Or hands to grasp them be.”

As spoke the brawny savage

Full wroth our comrades grew—

Baltasar de Gallegos

His heavy weapon drew,

And dealt the boaster such a stroke

As clave his body through.

Then rushed the swart Mobilians

Like hornets from their nest;

Against our bristling lances

Was bared each savage breast;

With arrow-head and club and stone,

Upon our band they prest.

“Retreat in steady order!

But slay them as ye go!”

Exclaimed the brave De Soto,

And with each word a blow

That sent a savage soul to doom

He dealt upon the foe.

“Strike well who would our honor

From spot or tarnish save!

Strike down the haughty Pagan,

The infidel and slave!

Saint Mary Mother sits above,

And smiles upon the brave.

“Strike! all my gallant comrades!

Strike! gentlemen of Spain!

Upon the traitor wretches

Your deadly anger rain,

Or never to your native land

Return in pride again!”

Then hosts of angry foemen

We fiercely held at bay,

Through living walls of Pagans

We cut our bloody way;

And though by thousands round they swarmed,

We kept our firm array.

At length they feared to follow;

We stood upon the plain,

And dressed our shattered columns;

When, slacking bridle rein,

De Soto, wounded as he was,

Led to the charge again.

For now our gallant horsemen

Their steeds again had found,

That had been fastly tethered

Unto the trees around,

Though some of these, by arrows slain,

Lay stretched upon the ground.

And as the riders mounted,

The foe, in joyous tones,

Gave vent to shouts of triumph,

And hurled a shower of stones;

But soon the shouts were changed to wails,

The cries of joy to moans.

Down on the scared Mobilians

The furious rush was led;

Down fell the howling victims

Beneath the horses’ tread;

The angered chargers trod alike

On dying and on dead.

Back to the wooden ramparts,

With cut and thrust and blow,

We drove the panting savage,

The very walls below,

Till those above upon our heads

Huge rocks began to throw.

Whenever we retreated

The swarming foemen came—

Their wild and matchless courage

Put even ours to shame—

Rushing upon our lances’ points,

And arquebuses’ flame.

Three weary hours we fought them,

And often each gave way;

Three weary hours, uncertain

The fortune of the day;

And ever where they fiercest fought

De Soto led the fray.

Baltasar de Gallegos

Right well displayed his might;

His sword fell ever fatal,

Death rode its flash of light;

And where his horse’s head was turned

The foe gave way in fright.

At length before our daring

The Pagans had to yield,

And in their stout enclosure

They sought to find a shield,

And left us, wearied with our toil,

The masters of the field.

Now worn and spent and weary,

Our force was scattered round,

Some seeking for their comrades,

Some seated on the ground,

When sudden fell upon our ears

A single trumpet’s sound.

“Up! ready make for storming!”

That speaks Moscoso near;

He comes with stainless sabre,

He comes with spotless spear;

But stains of blood and spots of gore

Await his weapons here.

Soon, formed in four divisions,

Around the order goes—

“To front with battle-axes!

No moment for repose.

At signal of an arquebus,

Rain on the gates your blows.”

Not long that fearful crashing,

The gates in splinters fall;

And some, though sorely wounded,

Climb o’er the crowded wall;

No rampart’s height can keep them back,

No danger can appall.

Then redly rained the carnage—

None asked for quarter there;

Men fought with all the fury

Born of a wild despair;

And shrieks and groans and yells of hate

Were mingled in the air.

Four times they backward beat us,

Four times our force returned;

We quenched in bloody torrents

The fire that in us burned;

We slew who fought, and those who knelt

With stroke of sword we spurned.

And what are these new forces,

With long, black, streaming hair?

They are the singing maidens

Who met us in the square;

And now they spring upon our ranks

Like she-wolves from their lair.

Their sex no shield to save them,

Their youth no weapon stayed;

De Soto with his falchion

A lane amid them made,

And in the skulls of blooming girls

Sank battle-axe and blade.

Forth came a wingèd arrow,

And struck our leader’s thigh;

The man who sent it shouted,

And looked to see him die;

The wound but made the tide of rage

Run twice as fierce and high.

Then cried our stout camp-master,

“The night is coming down;

Already twilight darkness

Is casting shadows brown;

We would not lack for light on strife

If once we burned the town.”

With that we fired the houses;

The ranks before us broke;

The fugitives we followed,

And dealt them many a stroke,

While round us rose the crackling flame,

And o’er us hung the smoke.

And what with flames around them,

And what with smoke o’erhead,

And what with cuts of sabre,

And what with horses’ tread,

And what with lance and arquebus,

The town was filled with dead.

Six thousand of the foemen

Upon that day were slain,

Including those who fought us

Outside upon the plain—

Six thousand of the foemen fell,

And eighty-two of Spain.

Not one of us unwounded

Came from the fearful fray;

And when the fight was over,

And scattered round we lay,

Some sixteen hundred wounds we bore

As tokens of the day.

And through that weary darkness,

And all that dreary night,

We lay in bitter anguish,

But never mourned our plight,

Although we watched with eagerness

To see the morning light.

And when the early dawning

Had marked the sky with red,

We saw the Moloch incense

Rise slowly overhead

From smoking ruins and the heaps

Of charred and mangled dead.

I knew the slain were Pagans,

While we in Christ were free,

And yet it seemed that moment

A spirit said to me:

“Henceforth be doomed while life remains

This sight of fear to see.”

And ever since that dawning

Which chased the night away,

I wake to see the corses

That thus before me lay;

And this is why in cloistered cell

I wait my latter day.

_BACON’S REBELLION._

Not an hour’s ride from Williamsburg, the seat of the venerable

William and Mary College, lie the ruins of Jamestown—part of the

tower of the old brick church, piles of bricks, and a number

of tombstones with quaint inscriptions, all half overgrown by

copse and brambles, being all that remains of the first town of

Virginia. At the time of its destruction it could not have been a

considerable place. It had the church, a state-house, and a few

dwellings built of imported bricks, not more than eighteen in

number, if so many. The other houses were probably framed, with

some log-huts. Our accounts of the place are meagre, and derived

from different sources.

[Illustration: JAMESTOWN AS IT IS.]

Nor have we a very full account of the circumstances attending its

destruction. So far as they are gathered they amount to this: Sir

William Berkeley, who at the outset of his administration had been

a good governor, was displaced during the troubles at home, and

when he returned, had been soured, and proved to be exacting and

tyrannical. Refusing to allow a force to be led against the Indian

enemy, the people took it in their own hands. Berkeley had a show

of right in the matter. Indian chiefs had come to John Washington,

the great-grandfather of George Washington, to treat of peace.

Washington was colonel of Westmoreland County, and he had these

messengers killed. Berkeley was indignant. “They came in peace,”

said he, “and I would have sent them in peace if they had killed

my father and mother.” The bloody act aroused the vengeance of the

Indians, and they fell on the frontier and massacred men, women,

and children. The governor considered it a just retribution, and

refused authority for reprisals. The people, who had no notion

that innocent parties should suffer for one man’s barbarous-deed,

organized. They chose Nathaniel Bacon, who was a popular young

lawyer, for their leader, and asked Berkeley to confirm him. This

request was refused. When some new murders by the Indians occurred,

Bacon marched against the enemy, and the governor proclaimed him

and his men rebels. When Bacon returned in triumph he was elected

a member of the assembly from Henrico County, and that assembly

passed laws of such a popular nature that Berkeley, in alarm, left

Jamestown. Bacon raised a force of five hundred men, and Berkeley,

who possessed high personal courage, met them alone. He uncovered

his breast and said, “A fair mark. Shoot!” But when Bacon explained

that he merely asked a commission, the people being in peril from

the enemy, this was granted; but no sooner had Bacon departed to

attack the Indians than Berkeley withdrew to the Eastern Shore,

where he collected a force of a thousand men from Accomac, to whom

he offered pay and plunder. With these he returned to Jamestown,

and proclaimed Bacon and his adherents rebels and traitors.

Bacon, having severely chastised the Indians, returned; but only

a few of his followers remained. This was in September, 1676. He

laid regular siege to Jamestown; but, as his force was so weak, he

feared a sortie by overwhelming numbers. To avert this, and gain

time to complete his works, he resorted to stratagem. By means

of a picked party, sent at night, he captured the wives of the

leading inhabitants. These, the next day, he placed on the summit

of a small work in sight of the town, and kept them thus exposed

until he had completed his lines, when he released them. Berkeley

sallied out, and was repulsed. He could not depend on his own men,

and that night he retired in his vessels. Bacon entered the town

next morning, and after consultation, it was agreed to destroy the

place. At seven o’clock in the evening, the torch was applied, and

in the morning the tower of the church and a few chimneys were all

that were left standing.

A number of Berkeley’s men now joined Bacon, who was undisputed

master of the colony; but dying shortly after, his party dispersed.

Berkeley, reinstated, took signal vengeance and executed about

twenty of the most prominent of Bacon’s friends. He was only

stopped by the positive orders of the King, by whom he was removed,

and Lord Culpepper, almost as great a tyrant, sent in his room.

_THE BURNING OF JAMESTOWN._

Mad Berkeley believed, with his gay cavaliers,

And the ruffians he brought from the Accomac shore,

He could ruffle our spirit by rousing our fears,

And lord it again as he lorded before:

It was—“Traitors, be dumb!”

And—“Surrender, ye scum!”

And that Bacon, our leader, was rebel, he swore.

A rebel? Not he! He was true to the throne;

For the King, at a word, he would lay down his life;

But to listen unmoved to the piteous moan

When the redskin was plying the hatchet and knife,

And shrink from the fray,

Was not the man’s way—

It was Berkeley, not Bacon, who stirred up the strife.

On the outer plantations the savages burst,

And scattered around desolation and woe;

And Berkeley, possessed by some spirit accurst,

Forbade us to deal for our kinsfolk a blow;

Though when, weapons in hand,

We made our demand,

He sullenly suffered our forces to go.

Then while we were doing our work for the crown,

And risking our lives in the perilous fight,

He sent lying messengers out, up and down,

To denounce us as outlaws—mere malice and spite;

Then from Accomac’s shore

Brought a thousand or more,

Who swaggered the country around, day and night.

Returning in triumph, instead of reward

For the marches we made and the battles we won,

There were threats of the fetters or bullet or sword—

Were these a fair guerdon for what we had done?

When this madman abhorred

Appealed to the sword,

And our leader said—“fight!” did he think we would run?

Battle-scarred, and a handful of men as we were,

We feared not to combat with lord or with lown,

So we took the old wretch at his word—that was fair;

But he dared not come out from his hold in the town,

Where he lay with his men,

Like a wolf in his den;

And in siege of the place we sat steadily down.

He made a fierce sally—his force was so strong

He thought the mere numbers would put us to flight—

But we met in close column his ruffianly throng,

And smote it so sore that we filled him with fright;

Then while ready we lay

For the storming next day,

He embarked in his ships, and escaped in the night.

The place was our own; could we hold it? why, no!

Not if Berkeley should gather more force and return;

But one course was left us to baffle the foe—

The birds would not come if the nest we should burn;

So the red, crackling fire

Climbed to roof-top and spire,

A lesson for black-hearted Berkeley to learn.

That our torches destroyed what our fathers had raised

On that beautiful isle, is it matter of blame?

That the houses we dwelt in, the church where they praised

The God of our Fathers, we gave to the flame?

That we smiled when there lay

Smoking ruins next day,

And nothing was left of the town but its name?

We won; but we lost when brave Nicholas died;

The spirit that nerved us was gone from us then;

And Berkeley came back in his arrogant pride

To give to the gallows the best of our men;

But while the grass grows

And the clear water flows,

The town shall not rise from its ashes again.

So, you come for your victim! I’m ready; but, pray,

Ere I go, some good fellow a full goblet bring.

Thanks, comrade! Now hear the last words I shall say

With the last drink I take. Here’s a health to the King,

Who reigns o’er a land

Where, against his command,

The rogues rule and ruin, and honest men swing.

_THE DEERFIELD MASSACRE._

In 1703, Colonel Johannis Schuyler, grandfather of the

Revolutionary general, Philip Schuyler, and uncle of the still more

famous Peter Schuyler, so distinguished in the Franco-Canadian war,

was mayor of Albany. From some Indians trading there he obtained

information that an attack on Deerfield was planned from Canada.

He sent word to the villagers, who prepared to meet it. The design

not having been carried out that summer, the people of Deerfield

supposed it to have been abandoned, and dismissed their fears.

The next year Vaudreuil, the governor of Canada, despatched a

force of three hundred French and Indians against the place. The

expedition was under the command of Hertel de Rouville, the son

of an almost equally famous partisan officer. With him were four

of his brothers. The raiders came by way of Lake Champlain to the

Onion River—then called the French—up which they advanced, and

passed on, marching on the ice, until they were near Deerfield.

The minister of the place, the Rev. Mr. Williams, unlike the rest

of the townsmen, had feared an attack for some time, and on his

application the provincial government had sent a guard of twenty

men. There were two or three block-houses, and around these some

palisades. De Rouville came near the town before daylight on the

29th of February, and learned by his spies the condition of the

place. Finding that the sentinels had gone to sleep two hours

before dawn, and that the snow had drifted in one place so as to

cover the palisades, he led a rush, and then dispersed his men in

small parties through the town to make a simultaneous attack. The

place was carried, with the exception of one garrison-house which

held out successfully. Forty-seven of the inhabitants were killed,

and nearly all the rest captured. The enemy, failing to reduce the

single block-house, retreated with their prisoners, taking up their

march for Canada. A band of colonists was hurriedly raised, and

pursued De Rouville; but they were beaten off after a sharp fight.

A hundred and twelve prisoners were carried away. A few were killed

on the march; the greater part were ransomed, and returned in about

two years.

[Illustration: ELEAZER WILLIAMS.]

Among the prisoners was the Rev. Mr. Williams. His wife, unable to

keep up with the party, was killed on the second day by her captor.

Two of his children had been killed during the sack. One of his

daughters, Eunice, while in captivity was converted to the Catholic

religion, and married with an Indian. She entirely adopted Indian

habits, and was pleased with her life. Afterwards she occasionally

visited her friends in New England, but no persuasion would induce

her to remain there. A chronicler states, with a comical mixture

of surprise and indignation, “She uniformly persisted in wearing

her blankets and counting her beads.” One of her descendants

was a highly respected clergyman, the Rev. Eleazer Williams, who

died a few years since, and who during life became the subject of

controversy. Mr. Hansen wrote an article, and finally a book, “The

Lost Prince,” to prove that Mr. Williams was really the missing

Dauphin, Louis the Sixteenth. A look at the clergyman’s portrait

shows the half-breed features quite distinctly, though the claim

was plausibly put, and for a time had its ardent supporters.

_THE SACK OF DEERFIELD._

Of the onset fear-inspiring, and the firing and the pillage

Of our village, when De Rouville with his forces on us fell,

When, ere dawning of the morning, with no death-portending warning,

With no token shown or spoken, came the foemen, hear me tell.

High against the palisadoes, on the meadows, banks, and hill-sides,

At the rill-sides, over fences, lay the lingering winter snow;

And so high by tempest rifted, at our pickets it was drifted,

That its frozen crust was chosen as a bridge to bear the foe.

We had set at night a sentry, lest an entry, while the sombre

Heavy slumber was upon us, by the Frenchman should be made;

But the faithless knave we posted, though of wakefulness he boasted,

’Stead of keeping watch was sleeping, and his solemn trust betrayed.

Than our slumber none profounder; never sounder fell on sleeper,

Never deeper sleep its shadow cast on dull and listless frames;

But it fled before the crashing of the portals, and the flashing,

And the soaring, and the roaring, and the crackling of the flames.

Fell the shining hatchets quickly ’mid the thickly crowded women,

Growing dim in crimson currents from the pulses of the brain;

Rained the balls from firelocks deadly, till the melted snow ran redly

With the glowing torrent flowing from the bodies of the slain.

I, from pleasant dreams awaking at the breaking of my casement,

With amazement saw the foemen quickly enter where I lay;

Heard my wife and children’s screaming, as the hatchets woke their dreaming,

Heard their groaning and their moaning as their spirits passed away.

’Twas in vain I struggled madly as the sadly sounding pleading

Of my bleeding, dying darlings fell upon my tortured ears;

’Twas in vain I wrestled, raging, fight against their numbers waging,

Crowding round me there they bound me, while my manhood sank in tears.

At the spot to which they bore me, no one o’er me watched or warded;

There unguarded, bound and shivering, on the snow I lay alone;

Watching by the firelight ruddy, as the butchers dark and bloody

Slew the nearest friends and dearest to my memory ever known.

And it seemed, as rose the roaring blaze, up soaring, redly streaming

O’er the gleaming snow around me through the shadows of the night,

That the figures flitting fastly were the fiends at revels ghastly,

Madly urging on the surging, seething billows of the fight.

Suddenly my gloom was lightened, hope was heightened, though the shrieking,

Malice-wreaking, ruthless wretches death were scattering to and fro;

For a knife lay there—I spied it, and a tomahawk beside it

Glittering brightly, buried lightly, keen edge upward, in the snow.

Naught knew I how came they thither, nor from whither; naught to me then

If the heathen dark, my captors, dropped those weapons there or no;

Quickly drawn o’er axe-edge lightly, cords were cut that held me tightly,

Then, with engines of my vengeance in my hands, I sought the foe.

Oh, what anger dark, consuming, fearful, glooming, looming horrid,

Lit my forehead, draped my figure, leapt with fury from my glance;

’Midst the foemen rushing frantic, to their sight I seemed gigantic,

Like the motion of the ocean, like a tempest my advance.

Stoutest of them all, one savage left the ravage round and faced me;

Fury braced me, for I knew him—he my pleading wife had slain.

Huge he was, and brave and brawny, but I met the slayer tawny,

And with rigorous blow, and vigorous, clove his tufted skull in twain—

Madly dashing down the crashing bloody hatchet in his brain.

As I brained him rose their calling, “Lo! appalling from yon meadow

The Monedo of the white man comes with vengeance in his train!”

As they fled, my blows Titanic falling fast increased their panic,

Till their shattered forces scattered widely o’er the snowy plain.

[Illustration: “HUGE HE WAS, AND BRAVE AND BRAWNY, BUT I MET THE

SLAYER TAWNY.”]

Stern De Rouville then their error, born of terror, soon dispersing,

Loudly cursing them for folly, roused their pride with words of scorn;

Peering cautiously they knew me, then by numbers overthrew me;

Fettered surely, bound securely, there again I lay forlorn.

Well I knew their purpose horrid, on each forehead it was written—

Pride was smitten that their bravest had retreated at my ire;

For the rest the captives durance, but for me there was assurance

Of the tortures known to martyrs—of the terrible death by fire.

Then I felt, though horror-stricken, pulses quicken as the swarthy

Savage, or the savage Frenchman, fiercest of the cruel band,

Darted in and out the shadows, through the shivered palisadoes,

Death-blows dealing with unfeeling heart and never-sparing hand.

Soon the sense of horror left me, and bereft me of all feeling;

Soon, revealing all my early golden moments, memory came;

Showing how, when young and sprightly, with a footstep falling lightly,

I had pondered as I wandered on the maid I loved to name.

Her, so young, so pure, so dove-like, that the love-like angels whom a

Sweet aroma circles ever wheresoe’er they wave their wings,

Felt with her the air grow sweeter, felt with her their joy completer,

Felt their gladness swell to madness, silent grow their silver strings.

Then I heard her voice’s murmur breathing summer, while my spirit

Leaned to hear it and to drink it like a draught of pleasant wine;

Felt her head upon my shoulder drooping as my love I told her,

Felt the utterly pleased flutter of her heart respond to mine.

Then I saw our darlings clearly that more nearly linked our gladness;

Saw our sadness as a lost one sank from pain to happy rest;

Mingled tears with hers, and chid her, bade her by our love consider

How our dearest now was nearest to the blessed Master’s breast.

I had lost that wife so cherished, who had perished, passed from being,

In my seeing—I, unable to protect her or defend;

At that thought dispersed those fancies, born of woe-begotten trances,

While unto me came the gloomy present hour my heart to rend.

For I heard the firelocks ringing, fiercely flinging forth the whirring,

Blood-preferring leaden bullets from a garrisoned abode;

There it stood so grim and lonely, speaking of its tenants only,

When the furious leaden couriers from its loop-holes fastly rode.

And the seven who kept it stoutly, though devoutly triumph praying,

Ceased not slaying, trusting somewhat to their firelocks and their wives;

For while they the house were holding, balls the wives were quickly moulding—

Neither fearful, wild, nor tearful, toiling earnest for their lives.

Onward rushed each dusky leaguer, hot and eager, but the seven

Rained the levin from their firelocks as the Pagans forward pressed;

Melting at that murderous firing, back that baffled foe retiring,

Left there lying, dead or dying, ten, their bravest and their best.

[Illustration: “FOR WHILE THEY THE HOUSE WERE HOLDING, BALLS THE

WIVES WERE QUICKLY MOULDING.”]

Rose the red sun, straightly throwing from his glowing disk his brightness

On the whiteness of the snow-drifts and the ruins of the town—

On those houses well defended, where the foe in vain expended

Ball and powder, standing prouder, smoke-begrimed and scarred and brown.

Not for us those rays shone fairly, tinting rarely dawning early

With the pearly light and glistering of the March’s snowy morn;

Some were wounded, some were weary, some were sullen, all were dreary,

As the sorrow of that morrow shed its cloud of woe forlorn.

Then we heard De Rouville’s orders, “To the borders!” and the dismal,

Dark, abysmal fate before us opened widely as he spoke;

But we heard a shout in distance—into fluttering existence,

Brief but splendid, quickly ended, at the sound our hopes awoke.

’Twas our kinsmen armed and ready, sweeping steady to the nor’ward,

Pressing forward fleet and fearless, though in scanty force they came—

Cried De Rouville, grimly speaking, “Is’t our captives you are seeking?

Well, with iron we environ them, and wall them round with flame.

“With the toil of blood we won them, we’ve undone them with our bravery;

Off to slavery, then, we carry them or leave them lifeless here.

Foul my shame so far to wander, and my soldiers’ blood to squander

’Mid the slaughter free as water, should our prey escape us clear.

“Off, ye scum of peasants Saxon, and your backs on Frenchmen turning,

To our burning, dauntless courage proper tribute promptly pay;

Do you come to seize and beat us? Are you here to slay and eat us?

If your meat be Gaul and Mohawk, we will starve you out to-day.”

How my spirit raged to hear him, standing near him bound and helpless!

Never whelpless tigress fiercer howled at slayer of her young,

When secure behind his engines, he has baffled her of vengeance,

Than did I there, forced to lie there while his bitter taunts he flung.

For I heard each leaden missile whirr and whistle from the trusty

Firelock rusty, brought there after long-time absence from the strife,

And was forced to stand in quiet, with my warm blood running riot,

When for power to give an hour to battle I had bartered life.

All in vain they thus had striven; backward driven, beat and broken,

Leaving token of their coming in the dead around the dell,

They retreated—well it served us! their retreat from death preserved us,

Though the order for our murder from the dark De Rouville fell.

As we left our homes in ashes, through the lashes of the sternest

Welled the earnest tears of anguish for the dear ones passed away;

Sick at heart and heavily loaded, though with cruel blows they goaded,

Sorely cumbered, miles we numbered four alone that weary day.

They were tired themselves of tramping, for encamping they were ready,

Ere the steady twilight newer pallor threw upon the snow;

So they built them huts of branches, in the snow they scooped out trenches,

Heaped up firing, then, retiring, let us sleep our sleep of woe.

By the wrist—and by no light hand—to the right hand of a painted,

Murder-tainted, loathsome Pagan, with a jeer, I soon was tied;

And the one to whom they bound me, ’mid the scoffs of those around me,

Bowing to me, mocking, drew me down to slumber at his side.

As for me, be sure I slept not: slumber crept not on my senses;

Less intense is lovers’ musing than a captive’s bent on ways

To escape from fearful thralling, and a death by fire appalling;

So, unsleeping, I was keeping on the Northern Star my gaze.

There I lay—no muscle stirring, mind unerring, thought unswerving,

Body nerving, till a death-like, breathless slumber fell around;

Then my right hand cautious stealing, o’er my bed-mate’s person feeling,

Till each finger stooped to linger on the belt his waist that bound.

’Twas his knife—the handle clasping, firmly grasping, forth I drew it,

Clinging to it firm, but softly, with a more than robber’s art;

As I drove it to its utter length of blade, I heard the flutter

Of a snow-bird—ah! ’twas no bird! ’twas the flutter of my heart.

Then I cut the cord that bound me, peered around me, rose uprightly,

Stepped as lightly as a lover on his blessed bridal day;

Swiftly as my need inclined me, kept the bright North Star behind me,

And, ere dawning of the morning, I was twenty miles away.

_THE LEWISES._

The Lewis family seem to have occupied a position as prominent,

and to have been as much identified with the local history of

the Colony of Virginia, as the Schuyler family with New York and

New Jersey. The John Lewis who is the hero of the ballad, though

less known than Andrew, who overcame Cornstalk at Point Pleasant,

and who was thought of before Washington for command of the

Continental army, was nevertheless a remarkable man. He was of that

Scotch-Irish race which settled the western part of Pennsylvania

and Virginia, and spread into North Carolina, Kentucky, and

Tennessee, making a people distinct in dialect and character,

and preserving a number of North of Ireland customs to this day.

John was a famous Indian fighter in his youth. At the time of the

defence described in the ballad he had grown quite old. His wife,

who came of a fighting family, aided him to drive off the enemy,

who would have endured almost any loss to have secured him as a

prisoner. They hated him intensely, and with just cause. When red

clover was introduced in that section, the savages believed that it

was the white clover, dyed in the blood of the Indians killed by

the Lewises.

_THE FIGHT OF JOHN LEWIS._

I.

To be captain and host in the fortress,

To keep his assailants at bay,

To battle a hundred of Mingos,

A score of the foemen to slay—

John Lewis did so in Augusta,

In days that have long gone away.

And I will maintain on my honor,

That never by poet was told

A fight half so worthy of mention,

Since those which the annals of old

Record as the wonderful doings

Of knights and of Paladins bold—

Ay, though about Richards or Rolands,

Or any such terrible dogs,

Who were covered with riveted armor

Of the pattern of Magog’s and Gog’s,

While Lewis wore brown linsey-woolsey,

And lived in a cabin of logs.

II.

They had started in arms from Fort Lewis,

One morn, in pursuit of the foe;

They had gone at the hour before dawning,

Over hills and through valleys below,

Leaving there, with the children and women,

John Lewis, unfitted to go.

Too weak for the toil of the travel,

Too old in the fight to have part,

Too feeble to stalk through the forest,

Yet fierce as a storm in his heart—

He chafed that without him his neighbors

Should thus to the battle-field start.

“How well,” he exclaimed, “I remember,

When over my threshold there came

A proud and an arrogant noble

To proffer me outrage and shame,

To bring to my household dishonor,

And offer my roof to the flame—

“I rose up erect in my manhood,

The sword of my fathers I drew;

In spite of his many retainers,

That arrogant noble I slew,

And then, with revenge fully sated,

Bade home and my country adieu.

“Ah, were I but stronger and younger,

How eager and ready, to-day,

I would move with the bravest and boldest,

As first in the perilous fray;

But now, while the rest do the fighting,

A laggard, with women I stay.”

The women they laughed when they heard him,

But one answered kindly, and said,

“Uncle John, though the days have departed

When our chiefest your orders obeyed,

Yet still, at the name of John Lewis,

The Mingos grow weak and afraid.

“Yon block-house were weak as a shelter,

Were blood-thirsty savages near,

Yet while you are at hand to defend us,

Not one of us women would fear,

But laugh at their malice and anger,

Though hundreds of foemen were here.”

Away to their work went the women—

Some drove off the cattle to browse;

Some swept from the hearth the cold embers;

Some started to milking the cows;

While Lewis went into the block-house,

And said unto Maggie, his spouse,

“Ah, would they but come to besiege me,

They’d find, though no more on the trail

I may move as in earlier manhood—

Though thus, in my weakness, I rail—

That to handle the death-dealing rifle,

These fingers of mine would not fail.”

III.

John Lewis, thy vaunt shall be tested,

John Lewis, thy boast shall be tried;

Two maidens are with thee for shelter,

The wife of thy youth by thy side;

And thy foemen pour down like a river

When spring-rains have swollen its tide.

They come from the depths of the forest,

They scatter in rage through the dell,

Five score, led by young Kiskepila,

And leap to their work with a yell,

Like the shrieks of an army of demons

Let loose from their prison in hell.

Oh, then there were shrieking and wailing,

And praying for mercy in vain;

Through the skulls of the hapless and helpless

The hatchet sank in to the brain;

And the slayers tore, fastly and fiercely,

The scalps from the heads of the slain.

By the ruthless and blood-thirsty Mingos

Encompassed on every side,

Cut off from escape to the block-house,

No way from pursuers to hide,

With a prayer to the Father Almighty,

Unresisting, the innocents died.

John Lewis, in torture of spirit,

Beheld them ply hatchet and knife,

And said, “Were I younger and stronger,

And fit as of yore for the strife!

Oh, had I from now until sunset

The vigor of earlier life!”

IV.

Unsated with horror and carnage,

Their arms all bedabbled with gore,

The foemen, with purpose determined,

Assembled the block-house before,

And their leader exclaimed, “Ho! John Lewis!

The Mingos are here at the door.

“The mystery-men of our nation

Declare that the blood you have shed

Has fallen so fastly and freely

The white clover flowers have grown red;

And that never will safety be with us

Till you are a prisoner or dead.

“So keep us not waiting, old panther;

Come forth from your log-bounded lair!

If in quiet you choose to surrender,

Your life at the least we will spare;

But refuse, and the scalping-knife bloody

Shall circle ere long in your hair.”

“Cowards all,” answered Lewis; “now mark me.

Beside me are good-rifles three;

I can sight on the bead true as ever,

My wife she can load, do you see?

You may war upon children and women,

Beware how you war upon me.”

They rushed on the block-house in anger;

They rushed on the block-house in vain;

Swift sped the round ball from the rifle—

The foremost invader was slain;

And ere they could bear back the fallen,

The dead of the foemen were twain.

So, firmly and sternly he fought them,

And steadily, six hours and more;

And often they rushed to the combat,

And often in terror forbore;

But never they wounded John Lewis,

Who slew of their number a score.

Ah, woe to your white hair, old hunter,

When powder and bullet be done;

You shall die by the slowest of tortures

When these shall the battle have won.

Look then to your Maker for mercy,

The Mingo will surely have none.

V.

A shout! ’tis the neighbors returning!

Now, Mingos, in terror fall back!

It is well that your sinews are lusty,

And well that no vigor ye lack;

He is best who in motion is fleetest

When the white man is out on his track.

Oh, then fell around them a terror;

Oh, then how the enemy ran;

For each hunter, in chosen position,

With coolness of vengeance began

To take a good aim with his rifle,

And send a sure shot to his man.

Oh, then there was racing and chasing,

And fastly they hurried away;

They feared at those husbands and fathers,

And dared not stand boldly at bay;

And in front of his men, Kiskepila

Ran slightly the fastest they say.

And well for the lives of the wretches

They fly from the brunt of the fight;

And well for their lives that around them

Are falling the shadows of night;

For life is in distance and darkness,

And death in the nearness and light.

But deep was the woe of the hunters,

And dark was the cloud o’er their life;

For some had been riven of children,

And some of both children and wife;

And woe to the barbarous Mingo,

If either should meet him in strife.

John Lewis said, calmly and coldly,

When gazing that eve on the slain—

“We will bury our dead on the morrow,

But let these red rascals remain;

And the wandering wolves and the buzzards

Will not of our kindness complain.”

Years after, when men called John Lewis

As brave as a brave man could be,

He lit him his pipe made of corn-cob,

And drawing a draught long and free—

“The red rascals kept me quite busy

With pulling the trigger,” said he.

“And though I got slightly the better

Of insolent foes in the strife,

I may as well own that my triumph

Was due unto Maggie, my wife;

For had she not loaded expertly,

The Mingos had reft us of life.

“And through all that terrible combat

She never was scared at the din;

But carefully loaded each rifle,

And prophesied that we would win—

Yet why should she tremble? her fathers

Were the terrible lords of Loch Linn.”

John Lewis commanded the fortress;

John Lewis was army as well;

John Lewis was master of ordnance;

John Lewis he fought as I tell;

And, gathered long since to his fathers,

John Lewis lies low in the dell.

But a braver old man, or a better,

Was never yet known to exist;

Not even in olden Augusta,

Where good men who died were not missed,

For the very particular reason—

Good men then were plenty, I wist.

_THE FIRST BLOOD DRAWN._

[Illustration: CLARK’S HOUSE, LEXINGTON.]

In the spring of 1775, General Gage, commanding the royal troops in

Boston, determined to seize the arms and stores which the colonists

had gathered at Concord. At midnight, on the eighteenth of April,

he sent eight hundred men, grenadiers and light infantry, under

Lieutenant-colonel Smith and Major Pitcairn, for that purpose. They

landed quietly at Phipps’s Farm, and to insure secrecy arrested all

they met on the march. General Warren, however, knew of it, and

sent Paul Revere with the news to John Hancock and Samuel Adams,

both of whom were at Clark’s House, in Lexington. Revere spread

the alarm. By two o’clock in the morning a company of minute-men

met on the green at Lexington, and after forming were dismissed,

with orders to re-assemble on call. In the mean while the ringing

of bells and firing of guns told the British that their movements

were known. Smith detached the greater part of his force, under

Pitcairn, with orders to push on to Concord. As they approached

Lexington they came upon the minute-men, who had hastily turned

out again. A pause ensued, both parties hesitating. Then Pitcairn

called on them to disperse. Not being obeyed, he moved his troops,

and a few random shots having been exchanged, gave the order to

fire. Four of the minute-men fell at the volley, and the rest

dispersed. As the British fired again, while the Americans were

retreating, some shots were returned. Four of the Americans were

killed, and three of the British were wounded. Joined by Smith and

his men, the British pushed on to Concord.

[Illustration: SAMUEL ADAMS.]

But the country was now thoroughly aroused. A strong party of

militia, though less in force than the enemy, had been gathered

under the command of Colonel Barrett, an old soldier, who had

served with Amherst and Abercrombie. Under his direction most of

the stores were removed to a place of safety. At seven in the

morning the British arrived at the place, and found two companies

of militia on the Common. These retreated to some high ground

about a mile back. The enemy then occupied the town, secured the

bridges, destroyed what stores had been left, and broke off the

trunnions of three 24-pound cannon. They also fired the town.

Meanwhile the forces of the Americans increased to four companies.

After consultation, Major Buttrick was sent with a detachment to

attack the enemy at the North Bridge. Here a fight ensued. Two

Americans and three British were killed, and several on both sides

were wounded. The British detachment retreated, and the Americans

took the bridge. The enemy, seeing Americans continually arriving,

were alarmed, and Smith ordered a speedy return to Boston, throwing

out flanking parties on the march. But it seemed as though armed

men sprang from every house and barn, or were lurking behind

every rock and tree. Shots came from every quarter, and were

mostly fatal. Charges had no effect. Driven from one point, fresh

assailants came from another. It seemed as though the entire

detachment would be slain or captured.

[Illustration: THE LEXINGTON MASSACRE.—[FROM AN OLD PRINT.]]

[Illustration: JOHN HANCOCK.]

Gage received word of the swarming of the minute-men and the peril

of his troops, and sent a brigade, with light artillery, under

Lord Percy, to reinforce Smith. This reached within a half mile of

Lexington at three o’clock in the afternoon, and forming a hollow

square around the wearied soldiers, allowed them a short time for

rest and refreshment. Then the whole body began its return march,

destroying houses and doing other mischief on the way. The country

was now up, the provincial troops came from all quarters, and it

was a general running engagement. At Prospect Hill there was a

sharp fight. Percy seemed in danger of being cut off; but another

and stronger reinforcement arriving, he was enabled to reach Boston.

[Illustration: FIGHT AT THE BRIDGE.]

_THE FIGHT AT LEXINGTON._

Tugged the patient, panting horses, as the coulter keen and thorough,

By the careful farmer guided, cut the deep and even furrow;

Soon the mellow mould in ridges, straightly pointing as an arrow,

Lay to wait the bitter vexing of the fierce, remorseless harrow—

Lay impatient for the seeding, for the growing and the reaping,

All the richer and the readier for the quiet winter-sleeping.

At his loom the pallid weaver, with his feet upon the treadles,

Watched the threads alternate rising, with the lifting of the heddles—

Not admiring that, so swiftly, at his eager fingers’ urging,

Flew the bobbin-loaded shuttle ’twixt the filaments diverging;

Only labor dull and cheerless in the work before him seeing,

As the warp and woof uniting brought the figures into being.

Roared the fire before the bellows; glowed the forge’s dazzling crater;

Rang the hammers on the anvil, both the lesser and the greater;

Fell the sparks around the smithy, keeping rhythm to the clamor,

To the ponderous blows, and clanging of each unrelenting hammer;

While the diamonds of labor, from the curse of Adam borrowed,

Glittered in a crown of honor on each iron-beater’s forehead.

Through the air there came a whisper, deepening quickly into thunder,

How the deed was done that morning that would rend the realm asunder;

How at Lexington the Briton mingled causeless crime with folly,

And a king endangered empire by an ill-considered volley.

Then each heart beat quick for vengeance, as the anger-stirring story

Told of brethren and of neighbors lying corses stiff and gory.

Stops the plough and sleeps the shuttle, stills the blacksmith’s noisy hammer,

Come the farmer, smith, and weaver, with a wrath too deep for clamor;

But their fiercely purposed doing every glance they give avouches,

As they handle rusty firelocks, powder-horns, and bullet-pouches;

As they hurry from the workshops, from the fields, and from the forges,

Venting curses deep and bitter on the latest of the Georges.

Matrons gather at the portals—some with children round them grouping,

Some are filled with exultation, some are sad of soul and drooping—

Gazing at our hasty levies as they march unskilled but steady,

Or prepare their long-kept firelocks, for the combat making ready—

Mingling smiles with tears, and praying for our men and those who lead them,

That the gracious Lord of battles to a triumph sure may speed them.

I was but a beardless stripling on that chilly April morning,

When the church-bells backward ringing, to the minute-men gave warning;

But I seized my father’s weapons—he was dead who one time bore them—

And I swore to use them stoutly, or to nevermore restore them;

Bade farewell to sister, mother, and to one than either dearer,

Then departed as the firing told of red-coats drawing nearer.

On the Britons came from Concord—’twas a name of mocking omen;

Concord nevermore existed ’twixt our people and the foemen—

On they came in haste from Concord, where a few had stood to fight them,

Where they failed to conquer Buttrick, who had stormed the bridge despite them;

On they came, the tools of tyrants, ’mid a people who abhorred them;

They had done their master’s bidding, and we purposed to reward them.

We, at Meriam’s Corner posted, heard the fifing and the drumming

In the distance creeping onward, which prepared us for their coming;

Soon we saw the lines of scarlet, their advance to music timing,

When our captain quickly bade us pick our flints and freshen priming.

There our little band of freemen, couched in silent ambush lying,

Watched the forces, full eight hundred, as they came with colors flying.

[Illustration: BATTLE-GROUND AT CONCORD.]

’Twas a goodly sight to see them; but we heeded not its splendor,

For we felt their martial bearing hate within our hearts engender,

Kindling fire within our spirits, though our eyes a moment watered,

As we thought on Moore and Hadley, and their brave companions slaughtered;

And we swore to deadly vengeance for the fallen to devote them,

And our rage grew hotter, hotter, as our well-aimed bullets smote them.

Then, in overpowering numbers, charging bayonet, came their flankers;

We were driven as the ships are, by a tempest, from their anchors.

But we loaded while retreating, and, regaining other shelter,

Saw their proudest on the highway in their life’s blood fall and welter;

Saw them fall, or dead or wounded, at our fire so quick and deadly,

While the dusty road was moistened with the torrent raining redly.

[Illustration: MERIAM’S CORNER, ON THE LEXINGTON ROAD.]

From behind the mounds and fences poured the bullets thickly, fastly;

From ravines and clumps of coppice leaped destruction grim and ghastly;

All around our leaguers hurried, coming hither, going thither,

Yet, when charged on by their forces, disappearing, none knew whither;

Buzzed around the hornets ever, newer swarms each moment springing,

Breaking, rising, and returning, yet continually stinging.

[Illustration: HALT OF TROOPS NEAR ELISHA JONES’S HOUSE.]

When to Hardy’s Hill their weary, waxing-fainter footsteps brought them,

There again the stout Provincials brought the wolves to bay and fought them;

And though often backward beaten, still returned the foe to follow,

Making forts of every hill-top, and redoubts of every hollow.

Hunters came from every farm-house, joining eagerly to chase them—

They had boasted far too often that we ne’er would dare to face them.

[Illustration: THE PROVINCIALS ON PUNKATASSET.]

How they staggered, how they trembled, how they panted at pursuing,

How they hurried broken columns that had marched to their undoing;

How their stout commander, wounded, urged along his frightened forces,

That had marked their fearful progress by their comrades’ bloody corses;

How they rallied, how they faltered, how in vain returned our firing,

While we hung upon their footsteps with a zealousness untiring.

With nine hundred came Lord Percy, sent by startled Gage to meet them,

And he scoffed at those who suffered such a horde of boors to beat them;

But his scorn was changed to anger, when on front and flank were falling,

From the fences, walls, and roadside, drifts of leaden hail appalling;

And his picked and chosen soldiers, who had never shrunk in battle,

Hurried quicker in their panic when they heard the firelocks rattle.

Tell it not in Gath, Lord Percy, never Ascalon let hear it,

That you fled from those you taunted as devoid of force and spirit;

That the blacksmith, weaver, farmer, leaving forging, weaving, tillage,

Fully paid with coin of bullets base marauders for their pillage;

They, you said, would fly in terror, Britons and their bayonets shunning;

But the loudest of the boasters proved the foremost in the running.

Then round Prospect Hill they hurried, where we followed and assailed them;

They had stout and tireless muscles, or their limbs had surely failed them;

Stood abashed the bitter Tories, as the women loudly wondered

That a crowd of scurvy rebels chased to hold eleven hundred—

Chased to hold eleven hundred, grenadiers both light and heavy,

Leading Percy, of the Border, on a chase surpassing Chevy.

Into Boston marched their forces, musket-barrels brightly gleaming,

Colors flying, sabres flashing, drums were beating, fifes were screaming.

Not a word about their journey; from the general to the drummer,

Did you ask about their doings, than a statue each was dumber;

But the wounded in their litters, lying pallid, weak, and gory,

With a language clear and certain told the sanguinary story.

’Twas a dark and bloody lesson; it was bloody work to teach it;

But when sits on high Oppression, soaring fire alone can reach it.

Though but raw and rude Provincials, we were freemen, and contending

For the rights our fathers gave us, and a country worth defending;

And when foul invaders threaten wrong to hearthstone and to altar,

Shame were on the freeman’s manhood should he either fail or falter.

On the day the fight that followed, neighbor met and talked with neighbor;

First the few who fell they buried, then returned to daily labor.

Glowed the fire within the forges, ran the ploughshare down the furrow,

Clicked the bobbin-loaded shuttle—both our fight and toil were thorough;

If we labored in the battle, or the shop, or forge, or fallow,

Still there came an honest purpose, casting round our deeds a halo.

Though they strove again, these minions of Germaine and North and Gower,

They could never make the weakest of our band before them cower;

Neither England’s bribes nor soldiers, force of arms nor titles splendid,

Could deprive of what our fathers left as rights to be defended.

And the flame from Concord, spreading, kindled kindred conflagrations,

Till the Colonies United took their place among the nations.

[Illustration: MONUMENT AT CONCORD.]

_BOMBARDMENT OF FORT SULLIVAN._

[Illustration: WILLIAM MOULTRIE.]

[Illustration: PLAN OF FORT ON SULLIVAN’S ISLAND.]

The Provincial Congress of South Carolina, in 1775, appointed a

Committee of Safety to sit during its own recess, and to this

it delegated full power. The Committee fitted out a vessel,

which captured an English sloop, laden with powder, lying at

St. Augustine. The royal governor of the State sent couriers to

intercept the vessel, but they failed. The powder was brought to

Charleston, and part of it was used by Arnold in the siege of

Quebec. Later in the year Colonel Moultrie took possession of a

small fort standing on Sullivan’s Island, in Charleston Harbor. The

governor fled to the frigate _Tamar_, and the Committee of Safety

took charge of affairs. Fort Johnson, on James’s Island, was seized

and armed. Guns were mounted on Haddrell’s Point, and a fascine

battery made on Sullivan’s Island. Between these two the _Tamar_

and her consort were obliged to leave the harbor. Colonel Moultrie

was now ordered to build a strong fort on Sullivan’s Island, and

over three hundred guns were mounted on the various fortifications.

Colonel Gadsden was placed in command, and every preparation made

for a vigorous defence.

[Illustration: SOUTH CAROLINA FLAG.]

[Illustration: SULLIVAN’S ISLAND, AND THE BRITISH FLEET AT THE TIME

OF THE ATTACK.]

The Continental Congress knew that a combined naval and land

attack would be made on Charleston; and in April Brigadier-general

Armstrong was sent there to take command, but was superseded, on

the fourth of June, by Major-general Charles Lee, who had been sent

by Washington. He worked hard for the defence of the city, and was

supported with ardor and enthusiasm by the people. Troops flocked

in until there were between five and six thousand men in arms,

including the Northern troops that had come with Armstrong and

Lee. They were disposed at Fort Johnson, on James’s Island, under

Gadsden; a battery on Sullivan’s Island, under Thomson; in the fort

on the same island, under Moultrie; and at Haddrell’s Point, under

Lee.

The British arrived on the fourth of June, but it was not until

the twenty-eighth that they were ready to attack. During the

interval they had constructed batteries on Long Island, to silence

that of Thomson on Sullivan’s Island and cover the landing of the

storming-party of Clinton’s troops.

On the morning of the twenty-eighth of June the attack began. The

incidents are faithfully given in the ballad, and to that the

reader is referred.

_SULLIVAN’S ISLAND._

Stout Sir Henry Clinton spoke—

“It is time the power awoke

That upholds in these dominions

Royal right;

Set all sail, and southward steer,

And, instead of idling here,

Crush these rebel Carolinians

Who have dared to beard our might.”

Of his coming well we knew—

Far and wide the story flew,

And the many tongues of rumor

Swelled his force;

But we scorned his gathered might,

And, relying on the right,

Bade the braggart let his humor

For a battle take its course.

Neither idle nor dismayed,

As we watched the coming shade

Of the murky cloud that hovered

On our coast;

From the country far and near,

In we called the volunteer,

Till the ground around was covered

With the trampling of our host.

In their homespun garb arrayed,

Sturdy farmers to our aid

Came, as to a bridal lightly

Come the guests;

Leaving crops and kine and lands,

Trusty weapons in their hands,

And the fire of courage brightly

Burning in their manly breasts.

[Illustration: SIR HENRY CLINTON.

[From an English Print.]]

From the hills the hunters came—

Having dealt with meaner game,

Much they longed to meet the lions

Of the isles;

And ’twas pleasant there to see

With what stately step, and free,

Strode those restless-eyed Orions

Past our better-ordered files.

There were soldiers from the North,

Hailed as brothers by the swarth,

Keen, chivalric Carolinians

At their side—

Ah, may never discord’s fires,

Sons of heart-united sires

Who together fought the minions

Of a tyrant-king, divide!

Came the owner of the soil,

The mechanic from his toil,

And the student from the college—

Equal each;

They had gathered there to show

To the proud and cruel foe,

Who had come to court the knowledge,

What a people’s wrath could teach.

Watching Clinton, day by day,

From his vessels in the bay,

On Long Island beach debarking

Grenadiers,

In the fort at Sullivan’s isle,

With a grim and meaning smile,

Every scarlet soldier marking,

Stood our ready cannoneers.

Of palmetto logs and sand,

On a stretch of barren land,

Stands that rude but strong obstruction,

Keeping guard;

’Tis the shelter of the town—

They must take or break it down,

They must sweep it to destruction,

Or their farther path is barred.

’Twas but weak they thought to shield;

They were sure it soon would yield;

They had guns afloat before it,

Ten to one;

Yet long time their vessels lay

Idly rocking in the bay,

While the flag that floated o’er it

Spread its colors in the sun.

But at length toward the noon

Of the twenty-eighth of June,

We observed their force in motion

On the shore;

At the hour of half-past nine

Saw their frigates form in line,

Heard the krakens of the ocean

Ope their mighty jaws and roar.

On the decks we saw them stand,

Lighted matches held in hand,

Brawny sailors, stripped and ready

For the word;

Crawling to the royal’s head,

Saw the signal rise and spread;

And the order to be steady

To the waiting crews we heard.

Then the iron balls and fire,

From the lips of cannon dire,

In a blazing torrent pouring,

Roaring came;

And each dun and rolling cloud

That arose the ships to shroud,

Seemed a mist continual soaring

From some cataract of flame.

Moultrie eyed the _Bristol_ then—

She was foremost of the ten—

And these words, his eyes upon her,

Left his lips:

“Let them not esteem you boors;

Show that gentle blood of yours;

Pay the Admiral due honor,

And the line-of-battle ships.”

Back our balls in answer flew,

Piercing plank and timbers through,

Till the foe began to wonder

At our might;

While we laughed to hear the roar

Flung by Echo from the shore;

While we shouted to the thunder

Grandly pealing through the fight.

From Long Island Clinton came,

To surmount the wall of flame

That was built by Thomson’s rangers

On the east;

But he found a banquet spread

Where, with open hand and red,