SING A SONG OF SIXPENCE

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost

no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it

under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this

eBook or online at http://www.gutenberg.org/license.

Title: Sing a Song of Sixpence

Author: Mary Holdsworth

Release Date: July 07, 2012 [EBook #40154]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK SING A SONG OF SIXPENCE ***

Produced by Al Haines.

[Illustration: Cover]

[Transcriber’s note: the illustrations in this book were originally

black and white line drawings. They appear to have been colorized by a

previous owner of the book.]

[Illustration: Nellie]

SING A SONG OF SIXPENCE.

BY

MARY HOLDSWORTH.

EDINBURGH AND LONDON:

OLIPHANT, ANDERSON, & FERRIER.

1892

BY THE SAME AUTHOR.

_Uniform in Pretty Cloth Binding._

SING A SONG OF SIXPENCE. MARY, MARY, QUITE CONTRARY.

WHERE THE SKY FALLS. ADVENTURES OF KING CLO. A PRINCESS

IN DISGUISE. A STRANGER IN THE TEA.

[Illustration: Headpiece]

Sing a Song of Sixpence.

A brand new sixpence fresh from the Mint! How it sparkled and glittered

in the dancing sunlight! Such a treasure for a small girl to possess!

But then, on the other hand, what a heavy responsibility!

[Illustration: Nellie]

All day long it had been burning a hole in her pocket, and as for

learning lessons, not an idea would enter her head. Everything went in

at one ear and out of the other, as Miss Primmer sternly remarked when

Nellie could not say her poetry. But, indeed, Nellie _did_ try hard to

learn her lessons; she squeezed her eyes together as tightly as

possible, though how shutting her eyes was to prevent the lessons from

coming out of her ears was not very clear. "But _I must_ learn them

now," she sighed, "or Miss Primmer will keep me in to-morrow, and I

shan’t be able to go out with Nursie and Reggie to spend my sixpence.

Oh dear! I wish I could learn my poetry and keep it in, I guess I’d

better get a bit of cotton wool to put in my ears and then it _can’t_

come out. There, now!

"’Mary had a little lamb,

Its fleece was white as snow,

And everywhere that Mary went

The lamb was sure to go.’

"That’s lovely! I wish I’d a lamb. I think I’ll buy one with my

sixpence. Won’t it be nice? And I can keep it in the garden, and me and

Reggie can take it out for a walk. Oh, and have a blue ribbon round its

neck and a sash on! He shall have my blue sash, and I’ll save it some

of my milk from breakfast. Unless it’s chocolate creams. How many

should I get for sixpence? Loads, I should think! I _love_ chocs., but

I’d like a lamb too! I’ll buy them both--a lamb and some chocs. Lemme

see now. What was I saying? Oh, my poetry.

"’It followed her to school one day’--

Oh, and take it to school. Won’t it be fun? What will Miss Primmer say

when she sees my lamb? She won’t say nothing to a dear, darling little

lamb! I _love_ lambs! Me and Reggie will have some wool off it to make

some stockings for Pa. I’ll make them all by myself, and Pa will think

I’m dreffle clever, won’t he? And some for Ma, and Uncle Dick. Oh, and

Aunt Euphemia shall have some for her niggers. Where’s my sixpence

gone? It was in my pocket. Oh, here it is! What do they put the

Queen’s head on it for? And a crown. It does look funny, as though it

would tumble off. I wish I was the Queen and wore a crown. I’d have

lots of sixpences. I’d go to Miss Primmer’s and give all the little

girls one each, and then they could all have a lamb each and some chocs.

And I’d have lots of chocs.--_loads_ of them. I wish it was to-morrow

to spend my sixpence."

Nellie sat gazing dreamily into the nursery fire, with wide-open blue

eyes, "Lemme say my poetry again.

"’Mary had a little lamb’--

With a blue sash on. What shall I call my lamb?" She went on gazing

with loving eyes at her bright new sixpence. "I think I’ll call her the

Queen. You won’t mind my calling my lamb after you, do you?" she said

to her Majesty, who was looking very dignified indeed; at least, as

dignified as it was possible to look when she had to hold her head as

stiff as possible to keep the crown from toppling off. It must have

given her a crick in her neck.

Her Majesty smiled graciously.

"Oh, not at all, don’t mention it," she said politely.

"Thank you so much," said Nellie, who was sitting in front of the fire

with her hands clasped across her knee.

"Get up and make your curtsey; I suppose you know how," said her

Majesty.

"Oh yes, Miss Primmer always makes us curtsey when we come in and go

out," answered Nellie, getting up and making the best one she could.

"That is not very graceful. This is the way," the Queen said, coming

forward and showing her how to do it. "Only you see I have to keep my

head steady to keep the crown on, so it’s rather awkward."

Nellie bowed as she was directed, and the Queen returned the bow with

great dignity. Nellie was much impressed. Fancy the Queen bowing to

her! What lovely tales she would have to tell to-morrow!

"What are you going to do with your new sixpence?" asked her Majesty,

when she had seated herself again.

"I thought I’d buy a lamb, and then I could make a pair of socks for Pa

with the wool."

The Queen smiled. "Very sensible indeed," she said, patting Nellie on

the head; "and you might make me a pair too, you know."

Nellie’s eyes sparkled. "And will you really wear them?" she asked

eagerly.

"I _always_ wear stockings," said the Queen in an offended tone. "You

don’t suppose I go about barefoot, do you?"

"I did not mean that!" cried Nellie, aghast. The bare idea of such a

thing!

"And don’t make them too large," went on the Queen; "I am very

particular about the fit."

"I’d like to be a queen and wear a crown," said Nellie, after a pause.

Her Majesty smiled. "Indeed! And pray, what would you do if you were?"

"I’d buy a lamb for all the children at Miss Primmer’s. Oh, and

chocs.--such lots of chocs. And I’d put on my best frock every day, and

have cake every time I wanted it, and I’d have as many sixpences as I

liked, and----"

"Stop, that will do," said the Queen; "if you always wore your best

frock you’d soon want a new one, and then where would all your sixpences

be? And as for the cake, I always keep _my_ cupboards locked, so that

no one can take a piece without asking for it; and the honey cupboard.

I am very fond of honey."

"Yes, I know, we sing about it in school," said Nellie.

"Oh, indeed? you do, do you? That’s very nice. But what do you sing

about me?"

"Oh, we sing:--

"’Sing a song of sixpence, a pocket full of rye,

Four and twenty blackbirds baking in a pie.

When the pie was opened the birds began to sing,

Was not that a dainty dish to set before a king?

The king was in his counting house, counting out his money,

The queen was in the parlour eating bread and honey,

The maid was in the garden hanging out the clothes,

There came a little blackbird and snapped off her nose.’"

"That’s very pretty," said her Majesty; "I wish I could write poetry

like that."

"Can’t you?" asked Nellie, looking surprised; she thought queens could

do everything.

"No," said her Majesty with a sigh; "I never could, though I’ve often

tried."

"Try, try, try again," said Nellie. "We sing that in school too."

"Well, what shall it be about?" asked the Queen.

"Oh, about my lamb," said Nellie promptly.

"Where is it?" asked the Queen, putting on her spectacles. "I think

I’ll write about you."

"Here I am," cried a funny squeaky little voice, and there, if you

please, was the prettiest, fleeciest little white lamb you ever saw in

your life, with a blue ribbon round its neck, and Nellie’s best blue

sash tied in a bow round its tail.

"Oh, how sweet!" cried the Queen, clapping her hands.

The lamb tossed its head proudly.

"Come near and let me look at you, you pretty thing," said the Queen,

patting it. "Now I’ll write my poetry. Get me a bottle of ink and a

copy-book to write it in."

"Would not a slate be better," said Nelly politely, "and then you could

copy it neatly into your book afterwards, you know. That’s the way we

do at school."

"Well, yes, perhaps that would be best. I might make a blot."

Nellie got her slate and a piece of pencil with a nice point. The Queen

took it, and sat for about five minutes groaning and turning up her eyes

to the ceiling, but nothing came of it. Nellie watched her anxiously.

"Have you not ’most finished?" she asked after a while.

"_Could_ you tell me how to spell honey?" asked the Queen. "I quite

forget, it is so long since I went to school."

"I don’t know," said Nellie, "I have not learned that yet. I’ll get the

dictionary.

"There now," said the Queen triumphantly, holding up the slate for

Nellie to look at. It was written in large round letters, something

like Nellie’s writing, with double lines to keep it even.

"Oh dear, what can the matter be?

Dear, dear, what can the matter be?

Oh dear, what can the matter be?

Nellie’s so long making tea!

She promised to give me some bread and some honey,

Some cake and some jam--I gave her the money,

What can she be doing? It _is_ very funny, I _do_ want

my afternoon tea."

"There," said the Queen with a deep sigh, "you can’t say I never wrote

any poetry. By-the-by, don’t you think it’s nearly time the pie was

done?"

"Pie?" asked Nellie, looking surprised.

"Yes," said her Majesty sharply. "You said there were four and twenty

blackbirds baking in a pie, didn’t you? Just go and see if it’s done,

I’m getting hungry."

"But where is the king? You can’t have it without him?"

"Never mind him. Let me have the pie."

"Was it from the king’s counting house my sixpence came?"

"Of course," said the Queen testily. "Now go and see about that pie."

Nellie went. It was a most delicious pie, crisp and brown. It made her

mouth water to look at it.

"I do hope the Queen won’t be greedy and want to eat it all herself,"

she thought, as she took it in and put it on the table.

"Present it on one knee," commanded the Queen.

Nellie did so. The Queen seized the knife and cut open the pie. All the

blackbirds began singing so sweetly. It was the loveliest concert you

ever heard in your life.

"Now that’s what I call a most dainty dish," said her Majesty, looking

much pleased.

"But you are not going to eat the dear little birds?" asked Nellie

anxiously.

"Of course not," said the Queen pettishly. "Get me a bit of bread and

honey. You know how fond I am of it."

One of the blackbirds flew out of the window as Nellie went to the

cupboard to get out some honey for the Queen and a piece of cake for

herself.

"Cookey makes such nice cakes," she said, with her mouth full.

"You should not talk with your mouth full," said the Queen. "You can

give me one to taste."

Nellie went down on one knee and presented it the way she had been

shown. The Queen took it at once and began to eat it. Such big bites

she took too, which rather surprised Nellie, who had seen Miss Primmer

at afternoon tea daintily mincing thin wafers of bread and butter.

"What are you staring at?" asked the Queen. "I hate to be stared

at--it’s very rude. Get me my bread and honey at once."

Nellie presented that too on one knee.

"Have you not a drop of tea? I’m dreadfully thirsty," asked the Queen.

"I have nothing but my doll’s tea set, and they are rather tiny,"

answered Nelly doubtfully, going to the cupboard and getting them out.

"Never mind, I can drink all the more," said her Majesty, and indeed she

_did_ drink. Nellie had never seen anything like it. There was no time

for her to drink a drop herself, she was so busy waiting on the Queen.

After a bit she quite lost count of the number of cups she drank.

"Don’t you think you have drunk enough cups now?" she asked at length,

thinking it about time she had a cup of tea herself.

"Drunk enough cups indeed," said the Queen huffily, "as if I have drunk

_any_ cups."

Nellie was silent for a moment.

"It’s dreffel wicked to tell stories," she said, holding up one finger

warningly. "Do you know where you’ll go if you tell stories?"

"I shall go home," said the Queen, "if you are going to be rude;

besides, I have not told any stories."

"Oh! You said you had not drunk any cups, and you have drunk

_millions_."

The Queen drew herself up haughtily.

"Pray, how many cups did you put out?" she asked in a very dignified

manner.

"Six," answered Nellie promptly.

"Well, then, count them. There they are. One, two, three, four, five,

six. How can you say I have drunk any of them? and millions too. It is

you who are telling the stories. I _never_ drink cups. I drink tea."

Nellie did not know what to say to this. "Well, you drank plenty of

tea, then," she said. "You did not leave any for me."

"I think it is about time I went home, if that is the way you treat your

visitors," said her Majesty, highly offended. "It is very rude to tell

people how much they eat. I shan’t come to see you again. And after

letting you have that six-pence, too."

"It was Pa who gave it to me," said Nellie, who was a very truthful

child.

"Well, how did my head come on it then if it did not come from me in the

first place?"

Nellie could not answer a word.

"Well, I must be going," said the Queen, recovering her good humour now

that she had silenced Nellie.

Nellie was just making her a grand curtsey when the door burst open and

in rushed the maid, holding her handkerchief to her face.

"It’s the blackbird," she sobbed. "He’s snapped off my nose."

"Stick it on again," said the Queen.

Nellie ran to get some sticking plaster, and stuck it on as hard as she

could.

It looked rather funny, she thought, but could not exactly understand

why for a little while, until she discovered it was stuck on upside

down.

"You had better take it off again and put it on straight," said the

Queen. But nothing would induce it to come off, it was stuck on so

tight.

"I guess she’ll have to stand on her head to blow her nose," said

Nellie, thoughtfully.

[Illustration: Nellie]

"Of course, the very thing," assented the Queen, cheerfully. "Well, I

really must be going. Good-bye now, whatever, and don’t forget my

stockings," she continued, waving her hand in token of farewell, and she

vanished, banging the door after her.

Nellie woke up with a start.

"Why, Miss Nellie, whatever are you doing all in the dark? And you have

let the fire out too."

"Oh, Nursie, such lovely things have happened. The Queen has been here,

and my lamb; oh, and lots of things."

"The Queen, indeed! Fiddle-sticks," said Nursie, with a sniff of

disbelief.

"Yes, she was. And she had tea with me out of my doll’s tea-set. And

here’s my dear little lamb. Why, wherever has it gone?" asked Nellie,

rubbing her eyes and looking around.

[Illustration: Nellie]

"And what on earth is that wool sticking out of your ears? Have you the

ear-ache?"

"Oh, Nursie, I only put it there to keep my poetry from coming out."

"Well, I never did!" said Nursie, holding up her hands in surprise. "You

are the _queerest_ child!"

[Illustration: tailpiece]

[Illustration: headpiece]

The Story of a Robin

She was a strange child, and led a lonely life, shut up in the almost

deserted castle with no one but her miserly old grandfather and old

Nanny for company. It was no wonder that she grew up with curious

unchildlike fancies, which were yet not altogether unchildlike. Her

mind found food for itself in the woods with their ever-changing tints,

the sky, the clouds, the sunset, and last, but by no means least, the

restless, never-silent sea, which bathed the foot of the rock where

stood the picturesque old castle.

[Illustration: robin]

Of friends Elsie had none. The Squire could not afford to keep

company--he was as poor as a rat, he used to say. Old Nanny was nearly

as miserly as he--you would have said she counted the grains of oatmeal

that she put into the porridge; not a particle of anything was ever

wasted in that frugal household. Report said--but I am not responsible

for the truth of this statement--that the miser had once had a piece of

cheese which was always brought to table, not to eat, mind you, oh dear,

no! but so that the odour might give a relish to the dry bread! Elsie

had not even a dog for a companion--for that would have required, at

least, some food. She used to look out of her little turret window and

watch the clouds floating about in the sky, and the stars smiling down

at her as they twinkled merrily up above. The moon was a very great

friend of hers; she loved to see his broad cheerful face rising over the

tree tops, and peeping in at her latticed windows.

Almost the only living creatures that she could make friends with were

the bats and owls that found an abode in the ruined walls of the castle,

and the robins that came hopping merrily around in search of the crumbs

that were not there. She loved, too, to watch the spiders that came

crawling stealthily out of their webs to catch any unwary fly that might

be so bold as to venture into such an inhospitable mansion.

She had no toys--never in her life had she even seen a doll. Think of

that, little Dorothy, with your collection of all kinds, from the rag

baby to the beautiful wax and china ones with real hair and eyes that

open and shut, and with all the dolls’ clothes a child’s heart could

desire. She did not miss them--never having known the pleasure of such

possessions.

But one real live pet she had--a robin that used to come hopping on to

her window sill every morning, and for whom she saved a few crumbs from

her scanty breakfast unknown to "gran’fer" or old Nanny, who you may be

sure would never have countenanced such waste. He was a merry little

birdie, with such a knowing twinkle in his eyes, that seemed to say he

knew all about little Elsie and her ways, and was glad to come and cheer

her up, and to make up to her for the lack of other friends by singing

to her every morning his sweetest song. Fine times they had, too, when

"gran’fer" was busy counting his money, and old Nanny was out gathering

sticks. They never bought anything at Castle Grim that they could get

without paying for. "Castle Hopeful" she called it, though why she chose

such a very inappropriate name for it, it would be hard to say. If you

come to think of it though, there was some sense in it, seeing that it

left so many things to be hoped for--things that never came. As for

such a thing as a new hat or a new frock, _that_ was too great a treat

to be ever wished for. When the frock she wore would no longer hang on

the fragile little form, when the bony arms came out half a yard below

the sleeves, and the long thin legs from under the short skirt, then old

Nanny grudgingly took out of the moth-eaten old wardrobe an old one of

Elsie’s mother’s, and cut it down until the child could get inside it

with something like ease. To be sure Nanny was no dressmaker, and the

frock was neither pretty nor elegant; and as for fit, why, that was a

mere trifle not worthy of serious consideration. Elsie could have

jumped into it, but it was a frock, and that was enough. The little

fisher-children who used to come gathering sea-weed and shells on the

beach used to look up with wistful eyes at the lonely little figure in

the turret-window, singing and talking to herself; but she was never

allowed to speak to them--Nanny was very strict about that. Elsie was

one of the "quality," and must not mix with the fisher-children.

The child had learnt her letters, no one knew how. Moreover, she was

the happy possessor of a few ragged old books--minus the covers and a

few of the pages--which she had found in rummaging about in the old

lumber room amongst broken furniture that would not sell, but was too

good for firewood.

Such treasures these books were to Elsie--strange reading for a child,

but very precious to her all the same. No "Alice in Wonderland," no

"Little Folks," no "St Nicholas," or "Fairy Tales"; but the "Pilgrim’s

Progress," garnished with pictures--such pictures, enough to make your

hair stand on end,--Foxe’s "Book of Martyrs," and last, but by no means

least, that most delightful of all books, "Don Quixote." How Elsie

loved the Don and his bony steed! She knew all his adventures by

heart--all that were in the book, that is--for, of course, both the

beginning and the end were lost.

If you will promise not to mention it, I will tell you a great secret.

Elsie was writing a story herself. It was the nicest story you ever read

in your life; but it was not very easy to read, being written in large

badly-formed childish characters on odd leaves of old copy books, and

sometimes the story and the copies got rather mixed; and the spelling

was, to say the least of it, quite unique, but it was a lovely story for

all that. Perhaps some day you will read it yourself. Elsie used to

read it aloud to her little friend the robin, and he listened with his

pert little head on one side as he hopped about picking up the crumbs

she had saved with so much difficulty for him; he was a most grateful

little birdie, and never forgot a kindness. She always knew his tap!

tap! at the window, and used to run to open it for him. It is very nice

to have a little bird for a friend, for it never quarrels or sulks like

some little boys or girls do, when it cannot get its own way.

[Illustration: Elsie]

It was a bitterly cold day in December. The snow had been falling all

night, and when morning came the earth was covered with a beautiful soft

white carpet. It was lovely to look at. Elsie sat up in her little

turret chamber watching the happy little fisher-children snowballing

each other. She would have liked a game with them, but she knew that

Nanny would not let her go. It was so cold, too, for there was no fire

anywhere but in the kitchen, and Nanny was making what she called the

dinner, and was always very cross when Elsie got in the way, so Elsie

sat upstairs in her little turret chamber trying to warm her cold little

hands by wrapping them up in an old shawl which had certainly been a

good one in its day, but unluckily there was very little of it left.

After watching the children for a time, she crept downstairs into the

kitchen.

"Oh, Nanny, let me help you with the dinner," she said pleadingly, "it’s

so cold upstairs."

The old woman was not a bad sort, but she was rather cross; everything

had gone wrong with her that morning. First, she could not get any

sticks on account of the snow, and the ones she had were damp and would

not burn; then the Squire had grumbled at her for extravagance.

"Oh, get out of the way, you are more of a hindrance than a help," she

answered pettishly.

Elsie went back again to her little room and looked out of the window at

the pure white snow. How lovely it looked! She would just run out to

see what it was like on the soft white carpet. How happy the hardy

fisher-children looked, with their fresh glowing faces and sturdy limbs,

as they pelted one another with the soft powdery snow!

She put on her old shawl and her apology for a hat, and stole quietly

out to the enchanted land. Old Nanny saw her go, but took no notice,

muttering to herself as she went on with her household duties. The

fresh keen air made little Elsie feel quite gay and happy as she frisked

about revelling in her new-found liberty.

"Oh, the snow! the lovely snow! I wonder who put it up in the sky? I

wish I could go up to see who is making the dear little feathers. Is it

the Man in the Moon, I wonder? I’d like to see him make the feathers.

Perhaps if I go far enough I’ll get to the end of the world, and then

I’ll get up into the clouds, it does not look very far," she said to

herself.

On she went merrily, with her eyes eagerly fixed upon the near horizon;

but the way was long, and the poor little feet grew heavy and tired.

Her boots, much too large for her, and very thin, were wet through and

through, but still she struggled bravely on. The snow was falling

thickly and silently. The large flakes filled the air, blotting out the

familiar landscape. There was everywhere nothing to be seen but snow!

snow! snow!

"I wonder if this is the right way," thought Elsie, as she plodded

painfully along. "Perhaps gran’f’er will be cross if I get lost."

[Illustration: robin]

She turned round to try and retrace her steps, but the little footmarks

were covered with the fast falling snow, she could not see which way she

had come. For a time she wandered on wearily and aimlessly, until she

took a false step and felt herself slipping, slipping. Where? Was it

into the middle of the earth? or was it into Snow Land? Only Snow Land

was up above, and she was going down, down, down! In vain she tried to

keep her footing; she sank down into the drift. The snow came down

blinding and choking her. The cruel cold snow that looked so soft and

gentle and yielding. She shut her eyes to try to keep it out.

"I wonder if gran’fer will be sorry if his little girl is lost? and

Nanny? and oh! my dear little Robin, who’ll save him the crumbs if I

have to stop down here? My dear little Robin! I wish gran’fer would

come! I’m getting so sleepy!" and the poor tired child lay still with

closed eyes.

Tap! tap! tap! What was that on her forehead.

Elsie opened her heavy eyes and looked around. There was her own dear

little Robin flapping his wings and hovering around her. Was it a dream?

Elsie rubbed her eyes. No, there he was in reality, in his warm red and

brown coat.

"Oh dear Robin! fly home and tell gran’fer I’m lost in the snow!" she

cried entreatingly.

Robin perched his saucy little head on one side, and looked at her with

his bright twinkling eyes as though he quite understood what she said.

The snow had ceased falling, and the sky looked thick and yellow as

though it were lined with cotton wool. Elsie felt cold and stiff, and

her limbs ached--she felt she could not stay much longer in her snowy

bed.

"Fly home, Robin, and tell gran’fer," she repeated, and Robin flew away.

Elsie sighed, and half wished she had not sent him. He was company, at

any rate; she was tired of being alone. But gran’f’er would soon know,

and come to fetch her home.

She tried to keep her eyes open to watch for his coming, but it was hard

work, and oh! she was so tired! so tired! Would gran’fer never come?

Perhaps he was so busy counting his money that he would never think of

his little girl lying out there under the cruel snow!

At Castle Grim, in the old-fashioned kitchen, sat Nanny over the fire,

shivering, but not with the cold, though it was cold enough.

Where could the child be? The soup was ready for the master as soon as

he should come in, but the child, little Elsie, where was she? Presently

a shuffling step outside was heard, and the miser came in. He was a

curious looking figure, with scanty grey locks hanging over his stooping

shoulders. His clothes were green with age, but well brushed and

mended. He seated himself at the table, and looked round for his little

grand-daughter.

"Where is Elsie?" he asked with a frown.

The old woman’s voice trembled.

"She went out into the snow, and has not come back," she answered,

putting her apron to her eyes; "and these old bones are not fit to go

out to look for her."

The old man got up and went to the window. The dusk was beginning to

come on in the short December afternoon.

"Which way did she go?" he asked at length.

"I don’t know. I did not watch her go," mumbled the old woman. "I was

too busy--I can’t be always watching folks."

"We must track her footsteps," said the miser, getting his greatcoat.

But in the grounds in front of the house the snow lay in an unbroken

sheet; no signs of any footmarks--they were all covered by this time.

Nanny and the miser looked at each other in consternation.

"She is lost in the snow," muttered the old woman sitting down in front

of the fire, with her apron over her head, rocking herself to and fro.

The miser, too, sat down, and covering his face with his hands, groaned

aloud.

What was he to do? Where to go? On one side of the castle lay the sea,

on the other the moor. It was like looking for a needle in a bottle of

hay to search for her--and there were no tracks to follow. The old man

was greatly distressed; miser though he was, he had a man’s heart, and

in his own way he loved his little granddaughter, though, to be sure, he

loved money more--or thought he did. But the child was very dear to

him--she was all that was left to the lonely old man.

The pair sat in silence for a while, plunged in thought; suddenly the

miser arose.

"Light the lantern," he said briefly.

"What are you going to do with it, master?" she asked in a shrill

quavering treble.

"To search for the child. Be quick."

Nanny groaned. "You’ll go and get lost too," she whined. "And there’ll

be nobody left but me."

Tap, tap, tap, at the window pane.

"What’s that?" asked the old man sharply.

Nanny hobbled to the window and looked out; there was nobody.

Tap, tap, tap again at the window. The miser himself went this time and

opened it.

In flew a robin, hopping about with his head on one side, and his keen

twinkling eyes fixed upon the miser.

"Bless me! It’s a robin! What does it want? Crumbs? Can’t afford to

keep birds," said the old man gruffly.

Robin flew to the window, and then turned as if to say, "Follow me."

The old woman watched it curiously.

"Birds are queer creatures; you would almost say it knew where the child

was," she said.

"Eh! What?" asked the old man sharply, looking more attentively at the

bird.

Robin gave a little chirp, tapped at the window with its bill, and then

turned again as if to say "Why don’t you come?"

The miser brightened up.

"Dear me! I really think you are right," he said, again taking up the

lantern.

Robin flew out, stopping every now and then to see if the miser was

following him. On, on they went a weary way. The moon struggled hard

to pierce through the thick clouds, and shed a pale silvery light around

to guide them on their way.

At last, with a succession of little chirps, Robin stopped before

something that looked like a dark speck. The miser followed cautiously,

for he well knew the treacherous moors. He stood still while Robin

scraped away the snow from her face with his little bill, and there lay

poor little Elsie, fast asleep, nearly buried in the snow. Gran’f’er

very carefully lifted her out of the drift, and wrapping her in his

great coat, wended his way home with a great joy in his heart, Robin

hovering around all the way.

Old Nanny was sitting by the dying embers with her apron over her head,

rocking herself backwards and forwards, and crooning a doleful dirge;

but she sprang up joyfully when the old man entered with the child in

his arms.

"Make up the fire," were the first words he said. Nanny put on a small

stick.

"A good roaring fire," added the old man. Nanny could hardly believe

her ears, but she cautiously put on another stick.

The old man carefully laid Elsie down on the one arm-chair the room

possessed.

"More, put on more, pile it up the chimney, let us have a bright warm

fire to bring her back to life," he said, rubbing his hands. Nanny

nearly dropped with surprise. Never, never before during the fifty odd

years that she had lived at Castle Grim had such an order been given.

In a few minutes a bright cheerful fire was blazing on the hearth, and

the kettle singing lustily.

Restoratives were applied to the little white-faced child, and she was

well rubbed and wrapped in blankets. Soon she opened her eyes. The

first thing they lit upon was the robin, who had followed them in and

was hopping about with his head on one side, looking very proud and

clever indeed, as he had a right to be, for was it not he who had found

out where Elsie lay buried in the snow, and had brought gran’f’er to

look for her?

"Oh, Robin! dear Robin!" cried the child in a weak voice. "Dear

gran’f’er, it was Robin who came to tell you where I was. I sent him,

you know."

Gran’f’er, who had been sitting watching the pair, said suddenly, with

an air of great resolution--no one knew how much it cost him to say

it--"Robin is to have some crumbs every day. I am very poor, and it

will nearly ruin me, but he shall have them."

Elsie’s eyes sparkled. "Oh gran’f’er! My own dear little Robin! Do

you really mean it?" she asked, clapping her weak little hands.

"Yes," said the old man firmly. "He shall have them."

"Dear little Robin, do you hear what gran’fer says?" cried Elsie

joyfully.

Robin looked very knowing indeed, as if he understood all about it, and

with a jerk of his perky little head, as much as to say, "Good-bye, I

must be off to my family, or else they’ll think I’m lost in the snow

too." Off he flew.

Who says birds have no sense? Not Elsie certainly, nor yet gran’fer, for

he thinks Elsie’s robin the most wonderful bird that ever lived.

Elsie is all right again now; and, indeed, she is not at all sorry she

was lost in the snow that day, for it has shown her how much gran’fer

loves her. And gran’fer--you would not know him--he has quite turned

over a new leaf, and is a miser no more. He now wears a good suit that

is not more than twenty years old, and has become quite liberal too, for

he no longer counts the sticks, nor the peas that are put into the soup.

He has kept his word about the crumbs; every morning a handful is thrown

out, which Robin, with his head very much on one side, and accompanied

by his family and a select circle of friends, picks up with great

relish, doing the honours in his best style. And not only that,

but--believe it or not as you will, it is certainly true--every

Christmas a sheaf of corn is nailed to the barn door for the birds, more

particularly for the robins, though all are welcome; and you never in

your life heard such a chirping and chattering as there is when this

interesting ceremony takes place. The birds come from far and near, the

fathers, the mothers, the sisters, the cousins, and the aunts, to join

in the feast; and gran’f’er, and Elsie, and old Nanny come out to watch

them eat their Christmas dinner.

[Illustration: birds]

[Illustration: tailpiece]

[Illustration: Molly]

*** END OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK SING A SONG OF SIXPENCE ***

A Word from Project Gutenberg

We will update this book if we find any errors.

This book can be found under: http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/40154

Creating the works from public domain print editions means that no one

owns a United States copyright in these works, so the Foundation (and

you!) can copy and distribute it in the United States without permission

and without paying copyright royalties. Special rules, set forth in the

General Terms of Use part of this license, apply to copying and

distributing Project Gutenberg™ electronic works to protect the Project

Gutenberg™ concept and trademark. Project Gutenberg is a registered

trademark, and may not be used if you charge for the eBooks, unless you

receive specific permission. If you do not charge anything for copies of

this eBook, complying with the rules is very easy. You may use this

eBook for nearly any purpose such as creation of derivative works,

reports, performances and research. They may be modified and printed and

given away – you may do practically _anything_ with public domain

eBooks. Redistribution is subject to the trademark license, especially

commercial redistribution.

The Full Project Gutenberg License

_Please read this before you distribute or use this work._

To protect the Project Gutenberg™ mission of promoting the free

distribution of electronic works, by using or distributing this work (or

any other work associated in any way with the phrase “Project

Gutenberg”), you agree to comply with all the terms of the Full Project

Gutenberg™ License available with this file or online at

http://www.gutenberg.org/license.

Section 1. General Terms of Use & Redistributing Project Gutenberg™

electronic works

*1.A.* By reading or using any part of this Project Gutenberg™

electronic work, you indicate that you have read, understand, agree to

and accept all the terms of this license and intellectual property

(trademark/copyright) agreement. If you do not agree to abide by all the

terms of this agreement, you must cease using and return or destroy all

copies of Project Gutenberg™ electronic works in your possession. If you

paid a fee for obtaining a copy of or access to a Project Gutenberg™

electronic work and you do not agree to be bound by the terms of this

agreement, you may obtain a refund from the person or entity to whom you

paid the fee as set forth in paragraph 1.E.8.

*1.B.* “Project Gutenberg” is a registered trademark. It may only be

used on or associated in any way with an electronic work by people who

agree to be bound by the terms of this agreement. There are a few things

that you can do with most Project Gutenberg™ electronic works even

without complying with the full terms of this agreement. See paragraph

1.C below. There are a lot of things you can do with Project Gutenberg™

electronic works if you follow the terms of this agreement and help

preserve free future access to Project Gutenberg™ electronic works. See

paragraph 1.E below.

*1.C.* The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation (“the

Foundation” or PGLAF), owns a compilation copyright in the collection of

Project Gutenberg™ electronic works. Nearly all the individual works in

the collection are in the public domain in the United States. If an

individual work is in the public domain in the United States and you are

located in the United States, we do not claim a right to prevent you

from copying, distributing, performing, displaying or creating

derivative works based on the work as long as all references to Project

Gutenberg are removed. Of course, we hope that you will support the

Project Gutenberg™ mission of promoting free access to electronic works

by freely sharing Project Gutenberg™ works in compliance with the terms

of this agreement for keeping the Project Gutenberg™ name associated

with the work. You can easily comply with the terms of this agreement by

keeping this work in the same format with its attached full Project

Gutenberg™ License when you share it without charge with others.

*1.D.* The copyright laws of the place where you are located also govern

what you can do with this work. Copyright laws in most countries are in

a constant state of change. If you are outside the United States, check

the laws of your country in addition to the terms of this agreement

before downloading, copying, displaying, performing, distributing or

creating derivative works based on this work or any other Project

Gutenberg™ work. The Foundation makes no representations concerning the

copyright status of any work in any country outside the United States.

*1.E.* Unless you have removed all references to Project Gutenberg:

*1.E.1.* The following sentence, with active links to, or other

immediate access to, the full Project Gutenberg™ License must appear

prominently whenever any copy of a Project Gutenberg™ work (any work on

which the phrase “Project Gutenberg” appears, or with which the phrase

“Project Gutenberg” is associated) is accessed, displayed, performed,

viewed, copied or distributed:

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away

or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License

included with this eBook or online at http://www.gutenberg.org

*1.E.2.* If an individual Project Gutenberg™ electronic work is derived

from the public domain (does not contain a notice indicating that it is

posted with permission of the copyright holder), the work can be copied

and distributed to anyone in the United States without paying any fees

or charges. If you are redistributing or providing access to a work with

the phrase “Project Gutenberg” associated with or appearing on the work,

you must comply either with the requirements of paragraphs 1.E.1 through

1.E.7 or obtain permission for the use of the work and the Project

Gutenberg™ trademark as set forth in paragraphs 1.E.8 or 1.E.9.

*1.E.3.* If an individual Project Gutenberg™ electronic work is posted

with the permission of the copyright holder, your use and distribution

must comply with both paragraphs 1.E.1 through 1.E.7 and any additional

terms imposed by the copyright holder. Additional terms will be linked

to the Project Gutenberg™ License for all works posted with the

permission of the copyright holder found at the beginning of this work.

*1.E.4.* Do not unlink or detach or remove the full Project Gutenberg™

License terms from this work, or any files containing a part of this

work or any other work associated with Project Gutenberg™.

*1.E.5.* Do not copy, display, perform, distribute or redistribute this

electronic work, or any part of this electronic work, without

prominently displaying the sentence set forth in paragraph 1.E.1 with

active links or immediate access to the full terms of the Project

Gutenberg™ License.

*1.E.6.* You may convert to and distribute this work in any binary,

compressed, marked up, nonproprietary or proprietary form, including any

word processing or hypertext form. However, if you provide access to or

distribute copies of a Project Gutenberg™ work in a format other than

“Plain Vanilla ASCII” or other format used in the official version

posted on the official Project Gutenberg™ web site

(http://www.gutenberg.org), you must, at no additional cost, fee or

expense to the user, provide a copy, a means of exporting a copy, or a

means of obtaining a copy upon request, of the work in its original

“Plain Vanilla ASCII” or other form. Any alternate format must include

the full Project Gutenberg™ License as specified in paragraph 1.E.1.

*1.E.7.* Do not charge a fee for access to, viewing, displaying,

performing, copying or distributing any Project Gutenberg™ works unless

you comply with paragraph 1.E.8 or 1.E.9.

*1.E.8.* You may charge a reasonable fee for copies of or providing

access to or distributing Project Gutenberg™ electronic works provided

that

- You pay a royalty fee of 20% of the gross profits you derive from

the use of Project Gutenberg™ works calculated using the method you

already use to calculate your applicable taxes. The fee is owed to

the owner of the Project Gutenberg™ trademark, but he has agreed to

donate royalties under this paragraph to the Project Gutenberg

Literary Archive Foundation. Royalty payments must be paid within 60

days following each date on which you prepare (or are legally

required to prepare) your periodic tax returns. Royalty payments

should be clearly marked as such and sent to the Project Gutenberg

Literary Archive Foundation at the address specified in Section 4,

“Information about donations to the Project Gutenberg Literary

Archive Foundation.”

- You provide a full refund of any money paid by a user who notifies

you in writing (or by e-mail) within 30 days of receipt that s/he

does not agree to the terms of the full Project Gutenberg™ License.

You must require such a user to return or destroy all copies of the

works possessed in a physical medium and discontinue all use of and

all access to other copies of Project Gutenberg™ works.

- You provide, in accordance with paragraph 1.F.3, a full refund of

any money paid for a work or a replacement copy, if a defect in the

electronic work is discovered and reported to you within 90 days of

receipt of the work.

- You comply with all other terms of this agreement for free

distribution of Project Gutenberg™ works.

*1.E.9.* If you wish to charge a fee or distribute a Project Gutenberg™

electronic work or group of works on different terms than are set forth

in this agreement, you must obtain permission in writing from both the

Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation and Michael Hart, the

owner of the Project Gutenberg™ trademark. Contact the Foundation as set

forth in Section 3. below.

*1.F.*

*1.F.1.* Project Gutenberg volunteers and employees expend considerable

effort to identify, do copyright research on, transcribe and proofread

public domain works in creating the Project Gutenberg™ collection.

Despite these efforts, Project Gutenberg™ electronic works, and the

medium on which they may be stored, may contain “Defects,” such as, but

not limited to, incomplete, inaccurate or corrupt data, transcription

errors, a copyright or other intellectual property infringement, a

defective or damaged disk or other medium, a computer virus, or computer

codes that damage or cannot be read by your equipment.

*1.F.2.* LIMITED WARRANTY, DISCLAIMER OF DAMAGES – Except for the “Right

of Replacement or Refund” described in paragraph 1.F.3, the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation, the owner of the Project

Gutenberg™ trademark, and any other party distributing a Project

Gutenberg™ electronic work under this agreement, disclaim all liability

to you for damages, costs and expenses, including legal fees. YOU AGREE

THAT YOU HAVE NO REMEDIES FOR NEGLIGENCE, STRICT LIABILITY, BREACH OF

WARRANTY OR BREACH OF CONTRACT EXCEPT THOSE PROVIDED IN PARAGRAPH 1.F.3.

YOU AGREE THAT THE FOUNDATION, THE TRADEMARK OWNER, AND ANY DISTRIBUTOR

UNDER THIS AGREEMENT WILL NOT BE LIABLE TO YOU FOR ACTUAL, DIRECT,

INDIRECT, CONSEQUENTIAL, PUNITIVE OR INCIDENTAL DAMAGES EVEN IF YOU GIVE

NOTICE OF THE POSSIBILITY OF SUCH DAMAGE.

*1.F.3.* LIMITED RIGHT OF REPLACEMENT OR REFUND – If you discover a

defect in this electronic work within 90 days of receiving it, you can

receive a refund of the money (if any) you paid for it by sending a

written explanation to the person you received the work from. If you

received the work on a physical medium, you must return the medium with

your written explanation. The person or entity that provided you with

the defective work may elect to provide a replacement copy in lieu of a

refund. If you received the work electronically, the person or entity

providing it to you may choose to give you a second opportunity to

receive the work electronically in lieu of a refund. If the second copy

is also defective, you may demand a refund in writing without further

opportunities to fix the problem.

*1.F.4.* Except for the limited right of replacement or refund set forth

in paragraph 1.F.3, this work is provided to you ‘AS-IS,’ WITH NO OTHER

WARRANTIES OF ANY KIND, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, INCLUDING BUT NOT LIMITED TO

WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTIBILITY OR FITNESS FOR ANY PURPOSE.

*1.F.5.* Some states do not allow disclaimers of certain implied

warranties or the exclusion or limitation of certain types of damages.

If any disclaimer or limitation set forth in this agreement violates the

law of the state applicable to this agreement, the agreement shall be

interpreted to make the maximum disclaimer or limitation permitted by

the applicable state law. The invalidity or unenforceability of any

provision of this agreement shall not void the remaining provisions.

*1.F.6.* INDEMNITY – You agree to indemnify and hold the Foundation, the

trademark owner, any agent or employee of the Foundation, anyone

providing copies of Project Gutenberg™ electronic works in accordance

with this agreement, and any volunteers associated with the production,

promotion and distribution of Project Gutenberg™ electronic works,

harmless from all liability, costs and expenses, including legal fees,

that arise directly or indirectly from any of the following which you do

or cause to occur: (a) distribution of this or any Project Gutenberg™

work, (b) alteration, modification, or additions or deletions to any

Project Gutenberg™ work, and (c) any Defect you cause.

Section 2. Information about the Mission of Project Gutenberg™

Project Gutenberg™ is synonymous with the free distribution of

electronic works in formats readable by the widest variety of computers

including obsolete, old, middle-aged and new computers. It exists

because of the efforts of hundreds of volunteers and donations from

people in all walks of life.

Volunteers and financial support to provide volunteers with the

assistance they need, is critical to reaching Project Gutenberg™’s goals

and ensuring that the Project Gutenberg™ collection will remain freely

available for generations to come. In 2001, the Project Gutenberg

Literary Archive Foundation was created to provide a secure and

permanent future for Project Gutenberg™ and future generations. To learn

more about the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation and how

your efforts and donations can help, see Sections 3 and 4 and the

Foundation web page at http://www.pglaf.org .

Section 3. Information about the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive

Foundation

The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation is a non profit

501(c)(3) educational corporation organized under the laws of the state

of Mississippi and granted tax exempt status by the Internal Revenue

Service. The Foundation’s EIN or federal tax identification number is

64-6221541. Its 501(c)(3) letter is posted at

http://www.gutenberg.org/fundraising/pglaf . Contributions to the

Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation are tax deductible to the

full extent permitted by U.S. federal laws and your state’s laws.

The Foundation’s principal office is located at 4557 Melan Dr.

S. Fairbanks, AK, 99712., but its volunteers and employees are scattered

throughout numerous locations. Its business office is located at 809

North 1500 West, Salt Lake City, UT 84116, (801) 596-1887, email

[email protected]. Email contact links and up to date contact

information can be found at the Foundation’s web site and official page

at http://www.pglaf.org

For additional contact information:

Dr. Gregory B. Newby

Chief Executive and Director

[email protected]

Section 4. Information about Donations to the Project Gutenberg Literary

Archive Foundation

Project Gutenberg™ depends upon and cannot survive without wide spread

public support and donations to carry out its mission of increasing the

number of public domain and licensed works that can be freely

distributed in machine readable form accessible by the widest array of

equipment including outdated equipment. Many small donations ($1 to

$5,000) are particularly important to maintaining tax exempt status with

the IRS.

The Foundation is committed to complying with the laws regulating

charities and charitable donations in all 50 states of the United

States. Compliance requirements are not uniform and it takes a

considerable effort, much paperwork and many fees to meet and keep up

with these requirements. We do not solicit donations in locations where

we have not received written confirmation of compliance. To SEND

DONATIONS or determine the status of compliance for any particular state

visit http://www.gutenberg.org/fundraising/donate

While we cannot and do not solicit contributions from states where we

have not met the solicitation requirements, we know of no prohibition

against accepting unsolicited donations from donors in such states who

approach us with offers to donate.

International donations are gratefully accepted, but we cannot make any

statements concerning tax treatment of donations received from outside

the United States. U.S. laws alone swamp our small staff.

Please check the Project Gutenberg Web pages for current donation

methods and addresses. Donations are accepted in a number of other ways

including checks, online payments and credit card donations. To donate,

please visit: http://www.gutenberg.org/fundraising/donate

Section 5. General Information About Project Gutenberg™ electronic

works.

Professor Michael S. Hart is the originator of the Project Gutenberg™

concept of a library of electronic works that could be freely shared

with anyone. For thirty years, he produced and distributed Project

Gutenberg™ eBooks with only a loose network of volunteer support.

Project Gutenberg™ eBooks are often created from several printed

editions, all of which are confirmed as Public Domain in the U.S. unless

a copyright notice is included. Thus, we do not necessarily keep eBooks

in compliance with any particular paper edition.

Each eBook is in a subdirectory of the same number as the eBook’s eBook

number, often in several formats including plain vanilla ASCII,

compressed (zipped), HTML and others.

Corrected _editions_ of our eBooks replace the old file and take over

the old filename and etext number. The replaced older file is renamed.

_Versions_ based on separate sources are treated as new eBooks receiving

new filenames and etext numbers.

Most people start at our Web site which has the main PG search facility:

http://www.gutenberg.org

This Web site includes information about Project Gutenberg™, including

how to make donations to the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive

Foundation, how to help produce our new eBooks, and how to subscribe to

our email newsletter to hear about new eBooks.

Sing a Song of Sixpence

Subjects:

Download Formats:

Excerpt

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost

no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it

under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this

eBook or online at http://www.gutenberg.org/license.

Read the Full Text

— End of Sing a Song of Sixpence —

Book Information

- Title

- Sing a Song of Sixpence

- Author(s)

- Holdsworth, Mary

- Language

- English

- Type

- Text

- Release Date

- July 7, 2012

- Word Count

- 9,479 words

- Library of Congress Classification

- PZ

- Bookshelves

- Browsing: Children & Young Adult Reading, Browsing: Fiction

- Rights

- Public domain in the USA.

Related Books

Maisie's merry Christmas

by Rhoades, Nina

English

1006h 44m read

Three little Trippertrots

by Garis, Howard Roger

English

630h 28m read

My friend Doggie; or, An only child

by Glasgow, G. R. (Geraldine Robertson)

English

34h 30m read

Dimple Dallas

by Blanchard, Amy Ella

English

588h 4m read

The house without windows & Eepersip's life there

by Follett, Barbara Newhall

English

579h 24m read

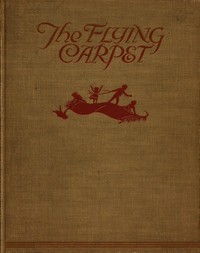

The flying carpet

English

804h 27m read