*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK 61178 ***

+-------------------------------------------------------+

|Several minor typographical errors have been corrected.|

| Many names are spelled several ways in the original.|

| No attempt has been made to correct |

| the various spellings. |

| (etext transcriber's note) |

+-------------------------------------------------------+

[Illustration: TEMPLE AT KANTONUGGUR, DINAJEPORE.]

HISTORY

OF

INDIAN AND EASTERN ARCHITECTURE;

BY JAMES FERGUSSON, D.C.L., F.R.S, M.R.A.S.,

FELLOW OF THE ROYAL INSTITUTE OF BRITISH ARCHITECTS,

MEMBER OF THE SOCIETY OF DILETTANTI,

ETC. ETC. ETC.

[Illustration: Tope at Manikyala.]

FORMING THE THIRD VOLUME OF THE NEW EDITION OF THE

‘HISTORY OF ARCHITECTURE.’

LONDON:

JOHN MURRAY, ALBEMARLE STREET.

1891.

_The right of Translation is reserved._

WORKS BY THE SAME AUTHOR.

ILLUSTRATIONS OF THE ROCK-CUT TEMPLES OF INDIA. 18 Plates in Tinted

Lithography, folio: with an 8vo. volume of Text, Plans, &c. 2_l._

7_s._ 6_d._ London, Weale, 1845.

PICTURESQUE ILLUSTRATIONS OF ANCIENT ARCHITECTURE IN HINDOSTAN. 24

Plates in Coloured Lithography, with Plans, Woodcuts, and

explanatory Text, &c. 4_l._ 4_s._ London, Hogarth, 1847.

AN HISTORICAL INQUIRY INTO THE TRUE PRINCIPLES OF BEAUTY IN ART,

more especially with reference to Architecture. Royal 8vo. 31_s._

6_d._ London, Longmans, 1849.

THE PALACES OF NINEVEH AND PERSEPOLIS RESTORED: An Essay on Ancient

Assyrian and Persian Architecture. 8vo. 16_s._ London, Murray,

1851.

THE ILLUSTRATED HANDBOOK OF ARCHITECTURE. Being a Concise and

Popular Account of the Different Styles prevailing in all Ages and

all Countries. With 850 Illustrations. 8vo. 26_s._ London, Murray,

1859.

RUDE STONE MONUMENTS IN ALL COUNTRIES, THEIR AGE AND USES. With 234

Illustrations. 8vo. London, Murray, 1872.

TREE AND SERPENT WORSHIP, OR ILLUSTRATIONS OF MYTHOLOGY AND ART IN

INDIA, in the 1st and 4th Centuries after Christ, 100 Plates and 31

Woodcuts. 4to. London, India Office; and W. H. Allen & Co. 2nd

Edition, 1873.

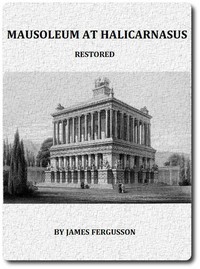

THE MAUSOLEUM AT HALICARNASSUS RESTORED, IN CONFORMITY WITH THE

REMAINS RECENTLY DISCOVERED. Plates 4to. 7_s._ 6_d._ London,

Murray, 1862.

AN ESSAY ON THE ANCIENT TOPOGRAPHY OF JERUSALEM; with restored

Plans of the Temple, and with Plans, Sections, and Details of the

Church built by Constantine the Great over the Holy Sepulchre, now

known as the Mosque of Omar. 16_s._ Weale, 1847.

THE HOLY SEPULCHRE AND THE TEMPLE AT JERUSALEM. Being the Substance

of Two Lectures delivered in the Royal Institution, Albemarle

Street, on the 21st February, 1862, and 3rd March, 1865. Woodcuts.

8vo. 7_s._ 6_d._ London, Murray, 1865.

AN ESSAY ON A PROPOSED NEW SYSTEM OF FORTIFICATION, with Hints for

its Application to our National Defences. 12_s._ 6_d._ London,

Weale, 1849.

THE PERIL OF PORTSMOUTH. FRENCH FLEETS AND ENGLISH FORTS. Plan.

8vo. 3_s._ London, Murray, 1853.

OBSERVATIONS ON THE BRITISH MUSEUM, NATIONAL GALLERY, and NATIONAL

RECORD OFFICE; with Suggestions for their Improvement. 8vo. London,

Weale, 1859.

LONDON. WM. CLOWES AND SONS, LIMITED, STAMFORD STREET AND CHARING

CROSS.

PREFACE.

During the nine years that have elapsed since I last wrote on this

subject,[1] very considerable progress has been made in the elucidation

of many of the problems that still perplex the student of the History of

Indian Architecture. The publication of the five volumes of General

Cunningham’s ‘Archæological Reports’ has thrown new light on many

obscure points, but generally from an archæological rather than from an

architectural point of view; and Mr. Burgess’s researches among the

western caves and the structural temples of the Bombay presidency have

added greatly not only to our stores of information, but to the

precision of our knowledge regarding them.

For the purpose of such a work as this, however, photography has

probably done more than anything that has been written. There are now

very few buildings in India--of any importance at least--which have not

been photographed with more or less completeness; and for purposes of

comparison such collections of photographs as are now available are

simply invaluable. For detecting similarities, or distinguishing

differences between specimens situated at distances from one another,

photographs are almost equal to actual personal inspection, and, when

sufficiently numerous, afford a picture of Indian art of the utmost

importance to anyone attempting to describe it.

These new aids, added to our previous stock of knowledge, are probably

sufficient to justify us in treating the architecture of India Proper in

the quasi-exhaustive manner in which it is attempted, in the first 600

pages of this work. Its description might, of course, be easily extended

even beyond these limits, but without plans and more accurate

architectural details than we at present possess, any such additions

would practically contribute very little that was valuable to the

information the work already contains.

The case is different when we turn to Further India. Instead of only 150

pages and 50 illustrations, both these figures ought at least to be

doubled to bring that branch of the subject up to the same stage of

completeness as that describing the architecture of India Proper. For

this, however, the materials do not at present exist. Of Japan we know

almost nothing except from photographs, without plans, dimensions, or

dates; and, except as regards Pekin and the Treaty Ports, we know almost

as little of China. We know a great deal about one or two buildings in

Cambodia and Java, but our information regarding all the rest is so

fragmentary and incomplete, that it is hardly available for the purposes

of a general history, and the same may be said of Burmah and Siam. Ten

years hence this deficiency may be supplied, and it may then be possible

to bring the whole into harmony. At present a slight sketch indicating

the relative position of each, and their relation to the styles of India

Proper, is all that can well be accomplished.

* * * * *

Although appearing as the third volume of the second edition of the

‘General History of Architecture,’ the present may be considered as an

independent and original work. In the last edition the Indian chapters

extended only to about 300 pages, with 200 illustrations,[2] and though

most of the woodcuts reappear in the present volume, more than half the

original text has been cancelled, and consequently at least 600 pages of

the present work are original matter, and 200 illustrations--and these

by far the most important--have been added. These, with the new

chronological and topographical details, present the subject to the

English reader in a more compact and complete form than has been

attempted in any work on Indian architecture hitherto published. It does

not, as I feel only too keenly, contain all the information that could

be desired, but I am afraid it contains nearly all that the materials

at present available will admit of being utilised, in a general history

of the style.

* * * * *

When I published my first work on Indian architecture thirty years ago,

I was reproached for making dogmatic assertions, and propounding

theories which I did not even attempt to sustain. The defect was, I am

afraid, inevitable. My conclusions were based upon the examination of

the actual buildings throughout the three Presidencies of India and in

China during ten years’ residence in the East, and to have placed before

the world the multitudinous details which were the ground of my

generalisations, would have required an additional amount of description

and engravings which was not warranted by the interest felt in the

subject at that time. The numerous engravings in the present volume, the

extended letterpress, and the references to works of later labourers in

the wide domain of Indian architecture, will greatly diminish, but

cannot entirely remove, the old objection. No man can direct his mind

for forty years to the earnest investigation of any department of

knowledge, and not become acquainted with a host of particulars, and

acquire a species of insight which neither time, nor space, nor perhaps

the resources of language will permit him to reproduce in their fulness.

I possess, to give a single instance, more than 3000 photographs of

Indian buildings, with which constant use has made me as familiar as

with any other object that is perpetually before my eyes, and to

recapitulate all the information they convey to long-continued scrutiny,

would be an endless, if not indeed an impossible undertaking. The

necessities of the case demand that broad results should often be given

when the evidence for the statements must be merely indicated or greatly

abridged, and if the conclusions sometimes go beyond the appended

proofs, I can only ask my readers to believe that the assertions are not

speculative fancies, but deductions from facts. My endeavour from the

first has been to present a distinct view of the general principles

which have governed the historical development of Indian architecture,

and my hope is that those who pursue the subject beyond the pages of the

present work, will find that the principles I have enunciated will

reduce to order the multifarious details, and that the details in turn

will confirm the principles. Though the vast amount of fresh knowledge

which has gone on accumulating since I commenced my investigations has

enabled me to correct, modify, and enlarge my views, yet the

classification I adopted, and the historical sequences I pointed out

thirty years since, have in their essential outlines been confirmed, and

will continue, I trust, to stand good. Many subsidiary questions remain

unsettled, but my impression is, that not a few of the discordant

opinions that may be observed, arise principally from the different

courses which inquirers have pursued in their investigations. Some men

of great eminence and learning, more conversant with books than

buildings, have naturally drawn their knowledge and inferences from

written authorities, none of which are contemporaneous with the events

they relate, and all of which have been avowedly altered and falsified

in later times. My authorities, on the contrary, have been mainly the

imperishable records in the rocks, or on sculptures and carvings, which

necessarily represented at the time the faith and feelings of those who

executed them, and which retain their original impress to this day. In

such a country as India, the chisels of her sculptors are, so far as I

can judge, immeasurably more to be trusted than the pens of her authors.

These secondary points, however, may well await the solution which time

and further study will doubtless supply. In the meanwhile, I shall have

realised a long-cherished dream if I have succeeded in popularising the

subject by rendering its principles generally intelligible, and can thus

give an impulse to its study, and assist in establishing Indian

architecture on a stable basis, so that it may take its true position

among the other great styles which have ennobled the arts of mankind.

* * * * *

The publication of this volume completes the history of the

‘Architecture in all Countries, from the earliest times to the present

day, in four volumes,’ and there it must at present rest. As originally

projected, it was intended to have added a fifth volume on ‘Rude Stone

Monuments,’ which is still wanted to make the series quite complete;

but, as explained in the preface to my work bearing that title, the

subject was not, when it was written, ripe for a historical treatment,

and the materials collected were consequently used in an argumentative

essay. Since that work was published, in 1872, no serious examination of

its arguments has been undertaken by any competent authority, while

every new fact that has come to light--especially in India--has served

to confirm me more and more in the correctness of the principles I then

tried to establish.[3] Unless, however, the matter is taken up

seriously, and re-examined by those who, from their position, have the

ear of the public in these matters, no such progress will be made as

would justify the publication of a second work on the same subject. I

consequently see no chance of my ever having an opportunity of taking up

the subject again, so as to be able to describe its objects in a more

consecutive or more exhaustive manner than was done in the work just

alluded to.

[Illustration: Buddha preaching. (From a fresco painting at Ajunta.)]

NOTE.

One of the great difficulties that meets every one attempting to write

on Indian subjects at the present day is to know how to spell Indian

proper names. The Gilchristian mode of using double vowels, which was

fashionable fifty years ago, has now been entirely done away with, as

contrary to the spirit of Indian orthography, though it certainly is the

mode which enables the ordinary Englishman to pronounce Indian names

with the greatest readiness and certainty. On the other hand, an attempt

is now being made to form out of the ordinary English alphabet a more

extended one, by accents over the vowels, and dots under the consonants,

and other devices, so that every letter of the Devanagari or Arabic

alphabets shall have an exact equivalent in this one.

In attempting to print Sanscrit or Persian books in Roman characters,

such a system is indispensable, but if used for printing Indian names in

English books, intended principally for the use of Englishmen, it seems

to me to add not only immensely to the repulsiveness of the subject, but

to lead to the most ludicrous mistakes. According to this alphabet for

instance, ḍ with dot under it represents a consonant we pronounce as r;

but as not one educated Englishman in 10,000 is aware of this fact, he

reads such words as Kattiwaḍ, Chîtoḍ, and Himaḍpanti as if spelt

literally with a d, though they are pronounced Kattiwar, Chittore, and

Himarpanti, and are so written in all books hitherto published, and the

two first are so spelt in all maps hitherto engraved. A hundred years

hence, when Sanscrit and Indian alphabets are taught in all schools in

England, it may be otherwise, but in the present state of knowledge on

the subject some simpler plan seems more expedient.

In the following pages I have consequently used the Jonesian system, as

nearly as may be, as it was used by Prinsep, or the late Professor

Wilson, but avoiding as far as possible all accents, except over vowels

where they were necessary for the pronunciation. Over such words as

Nâga, Râjâ, or Hindû--as in Tree and Serpent worship--I have omitted

accents altogether as wholly unnecessary for the pronunciation. An

accent, however, seems indispensable over the â in Lât, to prevent it

being read as Lath in English, as I have heard done, or over the î in

such words as Hullabîd, to prevent its being read as short bid in

English.

Names of known places I have in all instances tried to leave as they are

usually spelt, and are found on maps. I have, for instance, left

Oudeypore, the capital of the Rajput state, spelt as Tod and others

always spelt it, but, to prevent the two places being confounded, have

taken the liberty of spelling the name of a small unknown village, where

there is a temple, Udaipur--though I believe the names are the same. I

have tried, in short, to accommodate my spelling as nearly as possible

to the present state of knowledge or ignorance of the English public,

without much reference to scientific precision, as I feel sure that by

this means the nomenclature may become much less repulsive than it too

generally must be to the ordinary English student of Indian history and

art.

CONTENTS.

INTRODUCTION Page 3

BOOK I.

BUDDHIST ARCHITECTURE.

CHAP. PAGE

I. INTRODUCTION AND CLASSIFICATION 47

II. STAMBHAS OR LÂTS 52

III. STUPAS--Bhilsa Topes--Topes at Sarnath and in Behar--Amravati

Tope--Gandhara Topes--Jelalabad Topes--Manikyala Tope 57

IV. RAILS--Rails at Bharhut, Muttra Sanchi, and Amravati 84

V. CHAITYA HALLS--Behar Caves--Western Chaitya Halls, &c. 105

VI. VIHARAS OR MONASTERIES--Structural Viharas--Bengal and Western

Vihara Caves--Nassick, Ajunta, Bagh, Dhumnar, Kholvi, and Ellora

Viharas--Circular Cave at Junir 133

VII. GANDHARA MONASTERIES--Monasteries at Jamalgiri, Takht-i-Bahi, and

Shah Dehri 169

VIII. CEYLON--Introductory--Anuradhapura--Pollonarua 185

BOOK II.

JAINA ARCHITECTURE.

I. INTRODUCTORY 207

II. CONSTRUCTION--Arches--Domes--Plans--Sikras 210

III. NORTHERN JAINA STYLE--Palitana--Girnar--Mount

Abu--Parisnath--Gualior--Khajurâho 226

IV. MODERN JAINA STYLE--Jaina Temple, Delhi--Jaina Caves--Converted

Mosques 255

V. JAINA STYLE IN SOUTHERN INDIA--Bettus--Bastis 265

BOOK III.

ARCHITECTURE IN THE HIMALAYAS.

I. KASHMIR--Temples--Marttand--Avantipore--Bhaniyar 279

II. NEPAL--Stupas or Chaityas--Wooden Temples--Thibet--Temples at

Kangra 298

BOOK IV.

DRAVIDIAN STYLE.

I. INTRODUCTORY 319

II. DRAVIDIAN ROCK-CUT TEMPLES--Mahavellipore--Kylas, Ellora 326

III. DRAVIDIAN

TEMPLES--Tanjore--Tiruvalur--Seringham--Chillambaram--Ramisseram--

Mádura--Tinnevelly--Combaconum--Conjeveram--Vellore

and Peroor--Vijayanagar 340

IV. CIVIL ARCHITECTURE--Palaces at Mádura and Tanjore--Garden Pavilion

at Vijayanagar 380

BOOK V.

CHALUKYAN STYLE.

I. INTRODUCTORY--Temple at Buchropully--Kirti Stambha at

Worangul--Temples at Somnathpûr and Baillûr--The Kait Iswara at

Hullabîd--Temple at Hullabîd 386

BOOK VI.

NORTHERN OR INDO-ARYAN STYLE.

I. INTRODUCTORY--Dravidian and Indo-Aryan Temples at Badami--Modern

Temple at Benares 406

II. ORISSA--History--Temples at Bhuvaneswar, Kanaruc, Puri, Jajepur, and

Cuttack 414

III. WESTERN INDIA--Dharwar--Brahmanical Rock-cut Temples 437

IV. CENTRAL AND NORTHERN INDIA--Temples at Gualior, Khajurâho, Udaipur,

Benares, Bindrabun, Kantonuggur, Amritsur 448

V. CIVIL ARCHITECTURE--Cenotaphs--Palaces at Gualior, Ambêr,

Deeg--Ghâts--Reservoirs--Dams 470

BOOK VII.

INDIAN SARACENIC ARCHITECTURE.

I. INTRODUCTORY 489

II. GHAZNI--Tomb of Mahmúd--Gates of Somnath--Minars on the

Plain 494

III. PATHAN STYLE--Mosque at Old Delhi--Kutub Minar--Tomb of

Ala-ud-dîn--Pathan Tombs--Ornamentation of Pathan Tombs 498

IV. JAUNPORE--Mosques of Jumma Musjid and Lall Durwaza 520

V. GUJERAT--Jumma Musjid and other Mosques at Ahmedabad--Tombs and

Mosques at Sirkej and Butwa--Buildings in the Provinces 526

VI. MALWA--The Great Mosque at Mandu 540

VII. BENGAL--Kudam ul Roussoul Mosque, Gaur--Adinah Mosque,

Maldah 545

VIII. KALBURGAH--The Mosque at Kalburgah 552

IX. BIJAPUR--The Jumma Musjid--Tombs of Ibrahim and Mahmúd--The Audience

Hall--Tomb of Nawab Amir Khan, near Tatta 557

X. MOGUL ARCHITECTURE--Dynasties--Tomb of Mohammad Ghaus,

Gualior--Mosque at Futtehpore Sikri--Akbar’s Tomb, Secundra--Palace at

Delhi--The Taje Mehal--The Mûti Musjid--Mosque at Delhi--The Imambara,

Lucknow--Tomb of late Nawab, Junaghur 569

XI. WOODEN ARCHITECTURE--Mosque of Shah Hamadan, Srinugger 608

BOOK VIII.

FURTHER INDIA.

I. BURMAH--Introductory--Ruins of Thatún, Prome, and Pagan--Circular

Dagobas--Monasteries 611

II. SIAM--Pagodas at Ayuthia and Bangkok--Hall of Audience at

Bangkok--General Remarks 631

III. JAVA--History--Boro Buddor--Temples at Mendoet and Brambanam--Tree

and Serpent Temples--Temples at Djeing and Suku 637

IV. CAMBODIA--Introductory--Temples of Nakhon Wat, Ongcor Thom, Paten ta

Phrohm, &c. 663

BOOK IX.

CHINA.

I. INTRODUCTORY 685

II. PAGODAS--Temple of the Great Dragon--Buddhist

Temples--Taas--Tombs--Pailoos--Domestic Architecture 689

* * * * *

APPENDIX 711

INDEX 749

* * * * *

_DIRECTIONS TO BINDER._

Map of Buddhist and Jaina Localities _To face_ 47

Map of Indo-Aryan, Chalukyan, and Dravidian Localities _To face_ 279

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS.

NO. PAGE

1. Naga people worshipping the Trisul emblem of Buddha, on a fiery

pillar 46

2. Sri seated on a Lotus, with two elephants pouring water over

her 51

3. Lât at Allahabad 53

4. Assyrian honeysuckle ornament from capital of Lât, at

Allahabad 53

5. Capital of Sankissa 54

6. Capital of Lât in Tirhoot 54

7. Surkh Minar, Cabul 56

8. Relic Casket of Moggalana 62

9. Relic Casket of Sariputra 62

10. View of the Great Tope at Sanchi 63

11. Plan of Great Tope at Sanchi 63

12. Section of Great Tope at Sanchi 63

13. Tee cut in the rock on a Dagoba at Ajunta 64

14. Tope at Sarnath, near Benares 66

15. Panel on the Tope at Sarnath 68

16. Temple at Buddh Gaya with Bo-tree 70

17. Representation of a Tope from the Rail at Amravati 72

18. Tope at Bimeran 78

19. Tope, Sultanpore 78

20. Relic Casket from Tope at Manikyala 80

21. View of Manikyala Tope 81

22. Restored Elevation of the Tope at Manikyala 81

23. Elevation and Section of portion of Basement of Tope at

Manikyala 82

24. Relic Casket, Manikyala 82

25. Tree Worship: Buddh Gaya Rail 86

26. Relic Casket: Buddh Gaya Rail 86

27. Portion of Rail at Bharhut, as first uncovered 88

28. Tree and Serpent Worship at Bharhut 90

29. Rail at Sanchi 92

30. Rail, No. 2 Tope, Sanchi 93

31. Representation of Rail 93

32. Rail in Gautamiputra Cave, Nassick 94

33.[*] Northern Gateway of Tope at Sanchi 96

34. Bas-relief on left-hand Pillar, Northern Gateway 97

35. Ornament on right-hand Pillar, Northern Gateway 97

36. External Elevation of Great Rail at Amravati 100

37. Angle Pillar at Amravati 101

38. Slab from Inner Rail, Amravati 101

39. Dagoba (from a Slab), Amravati 102

40. Trisul Emblem 104

41. Plan of Chaitya Hall, Sanchi 105

42. Nigope Cave, Sat Ghurba group 108

43. Façade of Lomas Rishi Cave 109

44. Lomas Rishi Cave 109

45. Chaitya Cave, Bhaja 110

46. Façade of the Cave at Bhaja 111

47. Front of a Chaitya Hall 111

48. Trisul. Shield. Chakra. Trisul 112

49. Plan of Cave at Bedsa 113

50. Capital of Pillar in front of Cave at Bedsa 114

51. View on Verandah of Cave at Bedsa 114

52. Chaitya Cave at Nassick 115

53. Section of Cave at Karli 117

54. Plan of Cave at Karli 117

55. View of Cave at Karli 118

56. View of Interior of Cave at Karli 120

57. Interior of Chaitya Cave No. 10 at Ajunta 123

58. Cross-section of Cave No. 10 at Ajunta 123

59. Chaitya No. 19 at Ajunta 124

60. View of Façade Chaitya Cave No. 19 at Ajunta 125

61. Rock-cut Dagoba at Ajunta 126

62. Small Model found in the Tope at Sultanpore 126

63. Façade of the Viswakarma Cave at Ellora 128

64. Rail in front of Great Cave, Kenheri 130

65. Cave at Dhumnar 131

66. Great Rath at Mahavellipore 134

67. Diagram Explanatory of the Arrangement of a Buddhist Vihara of Four

Storeys in Height 134

68-69. Square and oblong Cells from a Bas-relief at Bharhut 135

70. Ganesa Cave 140

71. Pillar in Ganesa Cave, Cuttack 140

72. Upper Storey, Rani Gumpha 140

73. Tiger Cave, Cuttack 143

74. Cave No. 11 at Ajunta 145

75. Cave No. 2 at Ajunta 146

76. Caveat Bagh 146

77. Durbar Cave, Salsette 147

78. Nahapana Vihara, Nassick 149

79. Pillar in Nahapana Cave, Nassick 150

80. Pillar in Gautamiputra Cave, Nassick 150

81. Yadnya Sri Cave, Nassick 151

82. Pillar in Yadnya Sri Cave 152

83. Plan of Cave No. 16 at Ajunta 154

84. View of Interior of Vihara No. 16 at Ajunta 154

85. View in Cave No. 17 at Ajunta 155

86. Pillar in Vihara No. 17 at Ajunta 156

87. Great Vihara at Bagh 160

88. Plan of Dehrwarra, Ellora 163

89. Circular Cave, Junir 167

90. Section of Circular Cave, Junir 167

91. Round Temple and part of Palace from a bas-relief at Bharhut 168

92. Plan of Monastery at Jamalgiri 171

93. Plan of Monastery at Takht-i-Bahi 171

94. Corinthian Capital from Jamalgiri 173

95. Corinthian Capital from Jamalgiri 173

96. Plan of Ionic Monastery, Shah Dehri 176

97. Ionic Pillar, Shah Dehri 176

98. Elevation of front of Staircase, Ruanwelli Dagoba 190

99. View of Frontispiece of Stairs, Ruanwelli Dagoba 191

100. Stelæ at the end of Stairs, Abhayagiri Dagoba 192

101. Thuparamaya Tope 192

102. Lankaramaya Dagoba, A.D. 221 194

103. Pavilion with Steps at Anuradhapura 197

104. Moon Stone at Foot of Steps leading to the Platform of the Bo-tree,

Anuradhapura 197

105. The Jayta Wana Rama--Ruins of Pollonarua 201

106. Sat Mehal Prasada 202

107. Round House, called Watté Dajê in Pollonarua 203

108. View of City Gateway, Bijanagur 211

109. Gateway, Jinjûwarra 211

110. Radiating Arch 213

111. Horizontal Arch 213

112. Diagram of Roofing 213

113-114. Diagrams of Roofing 214

115. Diagram of Roofing 214

116. Diagram of Indian construction 215

117. Diagram of the arrangement of the pillars of a Jaina Dome 216

118. Diagram Plan of Jaina Porch 216

119. Diagram of Jaina Porch 217

120. Old Temple at Aiwulli 219

121. Temple at Aiwulli 220

122. Plan of Temple at Pittadkul 221

123. Restored Elevation of the Black Pagoda at Kanaruc 222

124. Diagram Plan and Section of the Black Pagoda at Kanaruc 223

125. The Sacred Hill of Sutrunjya, near Palitana 227

126. Temple of Neminatha, Girnar 230

127. Plan of Temple of Tejpala and Vastupala 232

128. Plan of Temple at Somnath 232

129. Temple of Vimala Sah, Mount Abu 235

130. Temple of Vimala Sah, Mount Abu 236

131. Pendant in Dome of Vimala Sah Temple at Abu 237

132. Pillars at Chandravati 238

133. Plan of Temple at Sadri 240

134. View in the Temple at Sadri 241

135. External View of the Temple at Sadri 242

136.[*] Jaina Temple at Gualior 244

137. Temple of Parswanatha at Khajurâho 245

138. Chaonsat Jogini, Khajurâho 246

139. The Ganthai, Khajurâho 248

140.[*] Temple at Gyraspore 249

141. Porch of Jaina Temple at Amwah, near Ajunta 251

142. Jaina Tower of Sri Allat Chittore 252

143. Tower of Victory erected by Khumbo Rana at Chittore 253

144.[*] View of Jaina Temples Sonaghur, in Bundelcund 256

145. View of the Temple of Shet Huttising at Ahmedabad 257

146. Upper part of Porch of Jaina Temple at Delhi 259

147. Entrance to the Indra Subha Cave at Ellora 262

148. Colossal Statue at Yannûr 268

149. Jaina Basti at Sravana Belgula 270

150. Jaina Temple at Moodbidri 271

151. Jaina Temple at Moodbidri 271

152. Pillar in Temple, Moodbidri 273

153. Pavilion at Gurusankerry 274

154. Tombs of Priests, Moodbidri 275

155. Stambha at Gurusankerry 276

156. Tomb of Zein-ul-ab-ud-din. Elevation of Arches 281

157. Takt-i-Suleiman. Elevation of Arches 282

158. Model of Temple in Kashmir 283

159. Pillar at Srinagar 284

160. Temple of Marttand 286

161. View of Temple at Marttand 287

162. Central Cell of Court at Marttand 288

163. Niche with Naga Figure at Marttand 290

164. Soffit of Arch at Marttand 291

165. Pillar at Avantipore 292

166. View in Court of Temple at Bhaniyar 293

167. Temple at Pandrethan 294

168. Temple at Payech 295

169. Temple at Mûlot in the Salt Range 296

170. Temple of Swayambunath, Nepal 302

171. Nepalese Kosthakar 303

172. Devi Bhowani Temple, Bhatgaon 304

173. Temple of Mahadeo and Krishna, Patan 306

174. Doorway of Durbar, Bhatgaon 307

175. Monoliths at Dimapur 309

176. Doorway of the Temple at Tassiding 313

177. Porch of Temple at Pemiongchi 314

178. Temples at Kiragrama, near Kote Kangra 316

179. Pillar at Erun of the Gupta age 317

180. Capital of Half Column from a Temple in Orissa 317

181. Raths, Mahavellipore 328

182. Arjuna’s Rath Mahavellipore 330

183. Perumal Pagoda, Mádura 331

184. Entrance to a Hindu Temple, Colombo 332

185. Tiger Cave at Saluvan Kuppan 333

186. Kylas at Ellora 334

187. Kylas, Ellora 335

188. Deepdan in Dharwar 337

189. Plan of Great Temple at Purudkul 338

190. Diagram Plan of Tanjore Pagoda 343

191. View of the Great Pagoda at Tanjore 344

192.[*] Temple of Soubramanya, Tanjore 345

193. Inner Temple at Tiruvalur 346

194. Temple at Tiruvalur 346

195.[*] View of the eastern half of the Great Temple at

Seringham 349

196. Plan of Temple of Chillambaram 351

197. View of Porch at Chillambaram 353

198. Section of Porch of Temple at Chillambaram 353

199.[*] Panned Temple or Pagoda at Chillambaram 354

200. Plan of Great Temple at Ramisseram 356

201. Central Corridor, Ramisseram 358

202. Plan of Tirumulla Nayak’s Choultrie 361

203. Pillar in Tirumulla Nayak’s Choultrie 361

204.[*] View in Tirumulla Nayak’s Choultrie, Mádura 363

205. Half-plan of Temple at Tinnevelly 366

206.[*] Gopura at Combaconum 368

207. Portico of Temple at Vellore 371

208. Compound Pillar at Vellore 372

209. Compound Pillar at Peroor 372

210. View of Porch of Temple of Vitoba at Vijayanagar 375

211.[*] Entrance through Gopura at Tarputry 376

212.[*] Portion of Gopura at Tarputry 377

213. Hall in Palace, Mádura 382

214. Court in Palace, Tanjore 383

215. Garden Pavilion at Vijayanagar 384

216. Temple at Buchropully 389

217. Doorway of Great Temple at Hammoncondah 390

218. Kirti Stambha at Worangul 392

219. Temple at Somnathpûr 394

220. Plan of Great Temple at Baillûr 395

221. View of part of Porch at Baillûr 396

222. Pavilion at Baillûr 397

223. Kait Iswara, Hullabîd 398

224. Plan of Temple at Hullabîd 399

225. Restored view of Temple at Hullabîd 400

226. Central Pavilion Hullabîd, East Front 402

227. Dravidian and Indo-Aryan Temples at Badami 411

228. Modern Temple at Benares 412

229. Diagram Plan of Hindu Temple 412

230. Temple of Parasurameswara 418

231. Temple of Mukteswara 419

232. Plan of Great Temple at Bhuvaneswar 421

233. View of Great Temple, Bhuvaneswar 422

234. Lower part of Great Tower at Bhuvaneswar 423

235. Plan of Raj Rani Temple 424

236. Doorway in Raj Rani Temple 425

237. Plan of Temple of Juganât at Puri 430

238. View of Tower of Temple, of Juganât 431

239. Hindu Pillar in Jajepur 433

240. Hindu Bridge at Cuttack 434

241. View of Temple of Papanatha at Pittadkul 438

242. Pillar in Kylas, Ellora 443

243. Plan of Cave No. 3, Badami 444

244. Section of Cave No. 3, Badami 444

245. Dhumnar Lena Cave at Ellora 445

246. Rock-cut Temple at Dhumnar 446

247. Saiva Temple near Poonah 446

248. Temple at Chandravati 449

249. Temple at Barrolli 450

250. Plan of Temple at Barrolli 450

251. Pillar in Barrolli 451

252.[*] Teli ka Mandir, Gualior 453

253.[*] Kandarya Mahadeo, Khajurâho 455

254. Plan of Kandarya Mahadeo, Khajurâho 456

255. Temple at Udaipur 457

256. Diagram explanatory of the Plan of Meera Baie’s Temple,

Chittore 458

257.[*] Temple of Vriji, Chittore 459

258. Temple of Vishveshwar 460

259. Temple of Scindiah’s Mother, Gualior 462

260. Plan of Temple at Bindrabun 463

261. View of Temple at Bindrabun 464

262. Balcony in Temple at Bindrabun 465

263. Temple at Kantonuggur 467

264.[*] The Golden Temple in the Holy Tank at Amritsur 468

265.[*] Cenotaph of Singram Sing at Oudeypore 471

266.[*] Cenotaph in Maha Sâti at Oudeypore 472

267.[*] Tomb of Rajah Baktawar at Ulwar 474

268.[*] Palace at Duttiah 477

269.[*] Palace at Ourtcha, Bundelcund 478

270. Balcony at the Observatory, Benares 481

271. Hall at Deeg 482

272. View from the Central Pavilion in the Palace at Deeg 483

273. Ghoosla Ghât, Benares 485

274. Bund of Lake Rajsamundra 487

275. Minar at Ghazni 495

276. Ornaments from the Tomb of Mahmúd at Ghazni 496

277. Plan of Ruins in Old Delhi 501

278. Section of part of East Colonnade at the Kutub, Old Delhi 503

279. Central Range of Arches at the Kutub 504

280. Minar of Kutub 505

281. Iron Pillar at Kutub 507

282. Interior of a Tomb at Old Delhi 509

283. Mosque at Ajmir 511

284. Great Arch in Mosque at Ajmir 512

285. Pathan Tomb at Shepree, near Gualior 515

286. Tomb at Old Delhi 516

287. Tomb of Shere Shah at Sasseram 516

288. Tomb of Shere Shah 517

289. Pendentive from Mosque at Old Delhi 519

290. Plan of Western Half of Courtyard of Jumma Musjid, Jaunpore 522

291. View of lateral Gateway of Jumma Musjid, Jaunpore 522

292. Lall Durwaza Mosque, Jaunpore 523

293. Plan of Jumma Musjid, Ahmedabad 528

294. Elevation of the Jumma Musjid 528

295. Plan of the Queen’s Mosque, Mirzapore 529

296. Elevation of the Queen’s Mosque, Mirzapore 529

297. Section of Diagram explanatory of the Mosques at Ahmedabad 529

298. Plan of Tombs and Mosque at Sirkej 531

299. Pavilion in front of tomb at Sirkej 532

300. Mosque at Mooháfiz Khan 532

301. Window in Bhudder at Ahmedabad 533

302. Tomb of Meer Abu Touráb 534

303. Plan and Elevation of Tomb of Syad Osmán 534

304. Tomb of Kutub-ul-Alum, Butwa 536

305. Plans of Tombs of Kutub-ul-Alum and his Son, Butwa 536

306. Plan of Tomb of Mahmúd Begurra near Kaira 538

307. Tomb of Mahmúd Begurra, near Kaira 538

308. Plan of Mosque at Mandu 542

309. Courtyard of Great Mosque at Mandu 543

310. Modern curved form of Roof 546

311. Kudam ul Roussoul Mosque, Gaur 548

312. Plan of Adinah Mosque, Maldah 549

313. Minar at Gaur 550

314. Mosque at Kalburgah 554

315. Half-elevation, half-section, of the Mosque at Kalburgah 555

316. View of the Mosque at Kalburgah 555

317. Plan of Jumma Musjid, Bijapur 559

318. Plan and Section of smaller Domes of Jumma Musjid 560

319. Section on the line A B through the Great Dome of the Jumma

Musjid 560

320. Tomb of Rozah of Ibrahim 561

321. Plan of Tomb of Mahmúd at Bijapur 562

322. Pendentives of the Tomb of Mahmúd, looking upwards 563

323. Section of Tomb of Mahmúd at Bijapur 564

324. Diagram illustrative of Domical Construction 565

325. Audience Hall, Bijapur 566

326. Tomb of Nawab Amir Khan, near Tatta, A.D. 1640 568

327. Plan of Tomb of Mohammad Ghaus, Gualior 576

328. Tomb of Mohammad Ghaus, Gualior 577

329. Carved Pillars in the Sultana’s Kiosk, Futtehpore Sikri 579

330. Mosque at Futtehpore Sikri 580

331. Southern Gateway of Mosque, Futtehpore Sikri 581

332. Hall in Palace at Allahabad 583

333. Plan of Akbar’s Tomb at Secundra 584

334. Diagram Section of one-half of Akbar’s Tomb at Secundra,

explanatory of its Arrangements 585

335. View of Akbar’s Tomb, Secundra 586

336. Palace at Delhi 592

337.[*] View of Taje Mehal 596

338. Plan of Taje Mehal, Agra 597

339. Section of Taje Mehal, Agra 597

340. Plan of Mûti Musjid 599

341. View in Courtyard of Mûti Musjid, Agra 600

342. Great Mosque at Delhi from the N.E. 601

343. Plan of Imambara at Lucknow 605

344. Tomb of the late Nawab of Junaghur 606

345. Mosque of Shah Hamadan, Srinugger 609

346. Plan of Ananda Temple 615

347. Plan of Thapinya 615

348. Section of Thapinya 616

349. View of the Temple of Gaudapalen 617

350. Kong Madú Dagoba 620

351. Shoëmadou Pagoda, Pegu 621

352. Half-plan of Shoëmadou Pagoda 621

353. View of Pagoda in Rangûn 623

354. Circular Pagoda at Mengûn 625

355. Façade of the King’s Palace, Burmah 627

356. Burmese Kioum 628

357. Monastery at Mandalé 629

358. Ruins of a Pagoda at Ayuthia 632

359. Ruins of a Pagoda at Ayuthia 633

360. The Great Tower of the Pagoda Wat-ching at Bangkok 634

361. Hall of Audience at Bangkok 635

362. Half-plan of Temple of Boro Buddor 645

363. Elevation and Section of Temple of Boro Buddor 645

364. Section of one of the smaller Domes at Boro Buddor 646

365. Elevation of principal Dome at Boro Buddor 646

366. View of central entrance and stairs at Boro Buddor 649

367. Small Temple at Brambanam 652

368. Terraced Temple at Panataram 655

369. View of the Maha Vihara, Anuradhapura 657

370. Plan of Temple of Nakhon Wat 668

371. Elevation of the Temple of Nakhon Wat 670

372. Diagram Section of Corridor, Nakhon Wat 671

373. View of Exterior of Nakhon Wat 671

374. View of Interior of Corridor, Nakhon Wat 672

375. General view of Temple of Nakhon Wat 675

376. Pillar of Porch, Nakhon Wat 676

377. Lower Part of Pilaster Nakhon Wat 677

378. One of the Towers of the Temple at Ongcor Thom 680

379. Temple of the Great Dragon 690

380. Monumental Gateway of Buddhist Monastery, Pekin 693

381. Temple at Macao 694

382. Porcelain Tower, Nankin 695

383. Pagoda in Summer Palace, Pekin 696

384. Tung Chow Pagoda 697

385. Chinese Grave 699

386. Chinese Tomb 699

387. Group of Tombs near Pekin 700

388. Pailoo near Canton 701

389. Pailoo at Amoy 702

390. Diagram of Chinese Construction 703

391. Pavilion in the Summer Palace, Pekin 705

392. Pavilion in the Summer Palace, Pekin 706

393. View in the Winter Palace, Pekin 707

394. Archway in the Nankau Pass 709

NOTE.--Those woodcuts in the above list marked with an asterisk are

borrowed from ‘L’Inde des Rajahs,’ published by Hachette et Cie,

Paris, translated and republished in this country by Messrs.

Chapman and Hall.

HISTORY

OF

INDIAN ARCHITECTURE.

INTRODUCTION.

It is in vain, perhaps, to expect that the Literature or the Arts of any

other people can be so interesting to even the best educated Europeans

as those of their own country. Until it is forced on their attention,

few are aware how much education does to concentrate attention within a

very narrow field of observation. We become familiar in the nursery with

the names of the heroes of Greek and Roman history. In every school

their history and their arts are taught, memorials of their greatness

meet us at every turn through life, and their thoughts and aspirations

become, as it were, part of ourselves. So, too, with the Middle Ages:

their religion is our religion; their architecture our architecture, and

their history fades so insensibly into our own, that we can draw no line

of demarcation that would separate us from them. How different is the

state of feeling, when from this familiar home we turn to such a country

as India. Its geography is hardly taught in schools, and seldom mastered

perfectly; its history is a puzzle; its literature a mythic dream; its

arts a quaint perplexity. But, above all, the names of its heroes and

great men are so unfamiliar and so unpronounceable, that, except a few

of those who go to India, scarcely any ever become so acquainted with

them, that they call up any memories which are either pleasing or worth

dwelling upon.

Were it not for this, there is probably no country--out of Europe at

least--that would so well repay attention as India. None, where all the

problems of natural science or of art are presented to us in so distinct

and so pleasing a form. Nowhere does nature show herself in such grand

and such luxurious features, and nowhere does humanity exist in more

varied and more pleasing conditions. Side by side with the intellectual

Brahman caste, and the chivalrous Rajput, are found the wild Bhîl and

the naked Gond, not antagonistic and warring one against the other, as

elsewhere, but living now as they have done for thousands of years, each

content with his own lot, and prepared to follow, without repining, in

the footsteps of his forefathers.

It cannot, of course, be for one moment contended that India ever

reached the intellectual supremacy of Greece, or the moral greatness of

Rome; but, though on a lower step of the ladder, her arts are more

original and more varied, and her forms of civilisation present an

ever-changing variety, such as are nowhere else to be found. What,

however, really renders India so interesting as an object of study is

that it is now a living entity. Greece and Rome are dead and have passed

away, and we are living so completely in the midst of modern Europe,

that we cannot get outside to contemplate it as a whole. But India is a

complete cosmos in itself; bounded on the north by the Himalayas, on the

south by the sea, on the east by impenetrable jungle, and only on the

west having one door of communication, across the Indus, open to the

other world. Across that stream, nation after nation have poured their

myriads into her coveted domain, but no reflex waves ever mixed her

people with those beyond her boundaries.

In consequence of all this, every problem of anthropology or ethnography

can be studied here more easily than anywhere else; every art has its

living representative, and often of the most pleasing form; every

science has its illustration, and many on a scale not easily matched

elsewhere. But, notwithstanding all this, in nine cases out of ten,

India and Indian matters fail to interest, because they are to most

people new and unfamiliar. The rudiments have not been mastered when

young, and, when grown up, few men have the leisure or the inclination

to set to work to learn the forms of a new world, demanding both care

and study; and till this is attained, it can hardly be hoped that the

arts and the architecture of India will interest a European reader to

the same extent as those styles treated of in the previous volumes of

this work.

Notwithstanding these drawbacks, it may still be possible to present the

subject of Indian architecture in such a form as to be interesting, even

if not attractive. To do this, however, the narrative form must be

followed as far as is compatible with such a subject. All technical and

unfamiliar names must be avoided wherever it is possible to do so, and

the whole accompanied with a sufficient number of illustrations to

enable its forms to be mastered without difficulty. Even if this is

attended to, no one volume can tell the whole of so varied and so

complex a history. Without preliminary or subsequent study it can hardly

be expected that so new and so vast a subject can be grasped; but one

volume may contain a complete outline of the whole, and enable any one

who wishes for more information to know where to look for it, or how to

appreciate it when found.

Whether successful or not, it seems well worth while that an attempt

should be made to interest the public in Indian architectural art;

first, because the artist and architect will certainly acquire broader

and more varied views of their art by its study than they can acquire

from any other source. More than this, any one who masters the subject

sufficiently to be able to understand their art in its best and highest

forms, will rise from the study with a kindlier feeling towards the

nations of India, and a higher--certainly a correcter--appreciation of

their social status than could be obtained from their literature, or

from anything that now exists in their anomalous social and political

position.

Notwithstanding all this, many may be inclined to ask, Is it worth while

to master all the geographical and historical details necessary to

unravel so tangled a web as this, and then try to become so familiar

with their ever-varying forms as not only to be able to discriminate

between the different styles, but also to follow them through all their

ceaseless changes?

My impression is that this question may fairly be answered in the

affirmative. No one has a right to say that he understands the history

of architecture who leaves out of his view the works of an immense

portion of the human race, which has always shown itself so capable of

artistic development. But, more than this, architecture in India is

still a living art, practised on the principles which caused its

wonderful development in Europe in the 12th and 13th centuries; and

there, consequently, and there alone, the student of architecture has a

chance of seeing the real principles of the art in action. In Europe, at

the present day, architecture is practised in a manner so anomalous and

abnormal that few, if any, have hitherto been able to shake off the

influence of a false system, and to see that the art of ornamental

building can be based on principles of common sense; and that, when so

practised, the result not only is, but must be, satisfactory. Those who

have an opportunity of seeing what perfect buildings the ignorant

uneducated natives of India are now producing, will easily understand

how success may be achieved, while those who observe what failures the

best educated and most talented architects in Europe are constantly

perpetrating, may, by a study of Indian models, easily see why this must

inevitably be the result. It is only in India that the two systems can

now be seen practised side by side--the educated and intellectual

European always failing because his principles are wrong, the feeble and

uneducated native as inevitably succeeding because his principles are

right. The Indian builders _think_ only of what they are doing, and how

they can best produce the effect they desire. In the European system it

is considered more essential that a building, especially in its details,

should be a correct _copy_ of something else, than good in itself or

appropriate to its purpose; hence the difference in the result.

In one other respect India affords a singularly favourable field to the

student of architecture. In no other country of the same extent are

there so many distinct nationalities, each retaining its old faith and

its old feelings, and impressing these on its art. There is consequently

no country where the outlines of ethnology as applied to art can be so

easily perceived, or their application to the elucidation of the various

problems so pre-eminently important. The mode in which the art has been

practised in Europe for the last three centuries has been very

confusing. In India it is clear and intelligible. No one can look at the

subject without seeing its importance, and no one can study the art as

practised there without recognising what the principles of the science

really are.

In addition, however, to these scientific advantages, it will

undoubtedly be conceded by those who are familiar with the subject that

for certain qualities the Indian buildings are unrivalled. They display

an exuberance of fancy, a lavishness of labour, and an elaboration of

detail to be found nowhere else. They may contain nothing so sublime as

the hall at Karnac, nothing so intellectual as the Parthenon, nor so

constructively grand as a mediæval cathedral; but for certain other

qualities--not perhaps of the highest kind, yet very important in

architectural art--the Indian buildings stand alone. They consequently

fill up a great gap in our knowledge of the subject, which without them

would remain a void.

HISTORY.

One of the greatest difficulties that exist--perhaps the greatest--in

exciting an interest in Indian antiquities arises from the fact, that

India has no history properly so called, before the Mahomedan invasion

in the 13th century. Had India been a great united kingdom, like China,

with a long line of dynasties and well-recorded dates attached to them,

the task would have been comparatively easy; but nothing of the sort

exists or ever existed within her boundaries. On the contrary, so far as

our knowledge extends, India has always been occupied by three or four

different races of mankind, who have never amalgamated so as to become

one people, and each of these races have been again subdivided into

numerous tribes or small nationalities nearly, sometimes wholly,

independent of each other--and, what is worse than all, not one of them

ever kept a chronicle or preserved a series of dates commencing from any

well-known era.[4]

The absence of any historical record is the more striking, because India

possesses a written literature equal to, if not surpassing in variety

and extent, that possessed by any other nation, before the invention, or

at least before the adoption and use, of printing. The Vedas themselves,

with their Upanishads and Brahmanas, and the commentaries on them, form

a literature in themselves of vast extent, and some parts of which are

as old, possibly older, than any written works that are now known to

exist; and the Puranas, though comparatively modern, make up a body of

doctrine mixed with mythology and tradition such as few nations can

boast of. Besides this, however, are two great epics, surpassing in

extent, if not in merit, those of any ancient nation, and a drama of

great beauty, written at periods extending through a long series of

years. In addition to those we have treatises on law, on grammar, on

astronomy, on metaphysics and mathematics, on almost every branch of

mental science--a literature extending in fact to some 10,000 or 11,000

works, but in all this not one book that can be called historical. No

man in India, so far as is known, ever thought of recording the events

of his own life or of repeating the previous experience of others, and

it was only at some time subsequent to the Christian Era that they ever

thought of establishing eras from which to date deeds or events.

All this is the more curious because in Ceylon we have, in the

‘Mahawanso,’ and other books of a like nature, a consecutive history of

that island, with dates which may be depended upon within very narrow

limits of error, for periods extending from B.C. 250 to the present

time. At the other extremity of India, we have also in the Raja

Tarangini of Kashmir, a work which Professor Wilson characterised as

“the only Sanscrit composition yet discovered to which the title of

History can with any propriety be applied.”[5] As we at present,

however, possess it, it hardly helps us to any historical data earlier

than the Christian Era, and even after that its dates for some centuries

are by no means fixed and certain.

In India Proper, however, we have no such guides as even these, but for

written history are almost wholly dependent on the Puranas. They do

furnish us with one list of kings’ names, with the length of their

reigns, so apparently truthful that they may, within narrow limits,

be depended upon. They are only, however, of one range of

dynasties--probably, however, the paramount one--and extend only from

the accession of Chandragupta--the Sandrocottus of the Greeks--B.C. 325,

to the decline of the Andra dynasty, about A.D. 400 or 408. It seems

probable we may find sufficient confirmation of these lists as far back

as the Anjana era, B.C. 691, so as to include the period marked by the

life and labours of Sakya Muni--the present Buddha--in our chronology,

with tolerable certainty. All the chronology before that period is

purposely and avowedly falsified by the introduction of the system of

Yugs, in order to carry back the origin of the Brahmanical system into

the regions of the most fabulous antiquity. From the 5th century

onwards, when the Puranas began to be put into their present form, in

consequence of the revival of the Brahmanical religion, instead of

recording contemporary events, they purposely confused them so as to

maintain their prophetic character, and prevent the detection of the

falsehood of their claim to an antiquity equal to that of the Vedas. For

Indian history after the 5th century we are consequently left mainly to

inscriptions on monuments or on copper-plates, to coins, and to the

works of foreigners for the necessary information with which the natives

of the country itself have neglected to supply us. These probably will

be found eventually to be at least sufficient for the purposes of

chronology. Already such progress has been made in the decipherment of

inscriptions and the arrangement of coins, that all the dynasties may be

arranged consecutively, and even the date of the reigns of almost all

the kings in the north of India have been already approximately

ascertained. In the south of India so much has not been done, but this

is more because there have been fewer labourers in the field than from

want of materials. There are literally thousands of inscriptions in the

south which have not been copied, and of the few that have been

collected only a very small number have been translated; but they are

such as to give us hope that, when the requisite amount of labour is

bestowed upon them, we shall be able to fix the chronology of the kings

of the south with a degree of certainty sufficient for all ordinary

purposes.[6]

It is a far more difficult task to ascertain whether we shall ever

recover the History of India before the time of the advent of Buddha, or

before the Anjana epoch, B.C. 691. Here we certainly will find no coins

or inscriptions to guide us, and no buildings to illustrate the arts, or

to mark the position of cities, while all ethnographic traces have

become so blurred, if not obliterated, that they serve us little as

guides through the labyrinth. Yet on the other hand there is so large a

mass of literature--such as it is--bearing on the subject, that we

cannot but hope that, when a sufficient amount of learning is brought to

bear upon it, the leading features of the history of even that period

may be recovered. In order, however, to render it available, it will not

require industry so much as a severe spirit of criticism to winnow the

few grains of useful truth out of the mass of worthless chaff this

literature contains. But it does not seem too much to expect even this,

from the severely critical spirit of the age. Meanwhile, the main facts

of the case seem to be nearly as follows, in so far as it is necessary

to state them, in order to make what follows intelligible.

ARYANS.

At some very remote period in the world’s history--for reasons stated in

the Appendix I believe it to have been at about the epoch called by the

Hindus the Kali Yug, or B.C. 3101--the Aryans, a Sanscrit-speaking

people, entered India across the Upper Indus, coming from Central Asia.

For a long time they remained settled in the Punjab, or on the banks of

the Sarasvati, then a more important stream than now, the main body,

however, still remaining to the westward of the Indus. If, however, we

may trust our chronology, we find them settled 2000 years before the

Christian Era, in Ayodhya, and then in the plenitude of their power. It

was about that time apparently that the event took place which formed

the groundwork of the far more modern poem known as the ‘Ramayana.’ The

pure Aryans, still uncontaminated by admixture with the blood of the

natives, then seem to have attained the height of their prosperity in

India, and to have carried their victorious arms, it may be, as far

south as Ceylon. There is, however, no reason to suppose that they at

that time formed any permanent settlements in the Deccan, but it was at

all events opened to their missionaries, and by slow degrees imbibed

that amount of Brahmanism which eventually pervaded the whole of the

south. Seven or eight hundred years after that time, or it may be about

or before B.C. 1200, took place those events which form the theme of the

more ancient epic known as the ‘Mahabharata,’ which opens up an entirely

new view of Indian social life. If the heroes of that poem were Aryans

at all, they were of a much less pure type than those who composed the

songs of the Vedas, or are depicted in the verses of the ‘Ramayana.’

Their polyandry, their drinking bouts, their gambling tastes, and love

of fighting, mark them as a very different race from the peaceful

shepherd immigrants of the earlier age, and point much more distinctly

towards a Tartar, trans-Himalayan origin, than to the cradle of the

Aryan stock in Central Asia. As if to mark the difference of which they

themselves felt the existence, they distinguished themselves, by name,

as belonging to a Lunar race, distinct from, and generally antagonistic

to, the Solar race, which was the proud distinction of the purer and

earlier Aryan settlers in India.

Five or six hundred years after this, or about B.C. 700, we again find a

totally different state of affairs in India. The Aryans no longer exist

as a separate nationality, and neither the Solar nor the Lunar race are

the rulers of the earth. The Brahmans have become a priestly caste, and

share the power with the Kshatriyas, a race of far less purity of

descent. The Vaisyas, as merchants and husbandmen, have become a power,

and even the Sudras are acknowledged as a part of the body politic; and,

though not mentioned in the Scriptures, the Nagas, or Snake people, had

become a most influential part of the population. They are first

mentioned in the ‘Mahabharata,’ where they play a most important part in

causing the death of Parikshit, which led to the great sacrifice for the

destruction of the Nagas by Janemajaya, which practically closes the

history of the time. Destroyed, however, they were not, as it was under

a Naga dynasty that ascended the throne of Magadha, in 691, that Buddha

was born, B.C. 623, and the Nagas were the people whose conversion

placed Buddhism on a secure basis in India, and led to its ultimate

adoption by Asoka (B.C. 250) as the religion of the State.[7]

Although Buddhism was first taught by a prince of the Solar race, and

consequently of purely Aryan blood, and though its first disciples were

Brahmans, it had as little affinity with the religion of the Vedas as

Christianity had with the Pentateuch, and its fate was the same. The one

religion was taught by one of Jewish extraction to the Jews and for the

Jews; but it was ultimately rejected by them, and adopted by the

Gentiles, who had no affinity of race or religion with the inhabitants

of Judæa. Though meant originally, no doubt, for Aryans, the Buddhist

religion was ultimately rejected by the Brahmans, who were consequently

utterly eclipsed and superseded by it for nearly a thousand years; and

we hear little or nothing of them and their religion till they

reappeared at the court of the great Vicramaditya (490-530), when their

religion began to assume that strange shape which it now still retains

in India. In its new form it is as unlike the pure religion of the Vedas

as it is possible to conceive one religion being to another; unlike

that, also, of the older portions of the ‘Mahabharata’; but a confused

mess of local superstitions and imported myths, covering up and hiding

the Vedantic and Buddhist doctrines, which may sometimes be detected as

underlying it. Whatever it be, however, it cannot be the religion of an

Aryan, or even of a purely Turanian people, because it was invented by

and for as mixed a population as probably were ever gathered together

into one country--a people whose feelings and superstitions it only too

truly represents.

DRAVIDIANS.

Although, therefore, as was hinted above, there might be no great

difficulty in recovering all the main incidents and leading features of

the history of the Aryans, from their first entry into India till they

were entirely absorbed into the mass of the population some time before

the Christian Era, there could be no greater mistake than to suppose

that their history would fully represent the ancient history of the

country. The Dravidians are a people who, in historical times, seem to

have been probably as numerous as the pure Aryans, and at the present

day form one-fifth of the whole population of India. As Turanians, which

they seem certainly to be, they belong, it is true, to a lower

intellectual status than the Aryans, but they have preserved their

nationality pure and unmixed, and, such as they were at the dawn of

history, so they seem to be now.

Their settlement in India extends to such remote pre-historic times,

that we cannot feel even sure that we should regard them as immigrants,

or, at least, as either conquerors or colonists on a large scale, but

rather as aboriginal in the sense in which that term is usually

understood. Generally it is assumed that they entered India across the

Lower Indus, leaving the cognate Brahui in Belochistan as a mark of the

road by which they came, and, as the affinities of their language seem

to be with the Ugrians and northern Turanian tongues, this view seems

probable.[8] But they have certainly left no trace of their migrations

anywhere between the Indus and the Nerbudda, and all the facts of their

history, so far as they are known, would seem to lead to an opposite

conclusion. The hypothesis that would represent what we know of their

history most correctly would place their original seat in the extreme

south, somewhere probably not far from Madura or Tanjore, and thence

spreading fan-like towards the north, till they met the Aryans on the

Vindhya Mountains. The question, again, is not of much importance for

our present purposes, as they do not seem to have reached that degree of

civilisation at any period anterior to the Christian Era which would

enable them to practise any of the arts of civilised life with success,

so as to bring them within the scope of a work devoted to the history of

art.

It may be that at some future period, when we know more of the ancient

arts of these Dravidians than we now do, and have become familiar with

the remains of the Accadians or early Turanian inhabitants of

Babylonia, we may detect affinities which may throw some light on this

very obscure part of history. At present, however, the indications are

much too hazy to be at all relied upon. Geographically, however, one

thing seems tolerably clear. If the Dravidians came into India in

historical times, it was not from Central Asia that they migrated, but

from Babylonia, or some such southern region of the Asiatic continent.

DASYUS.

In addition to these two great distinct and opposite nationalities,

there exists in India a third, which, in pre-Buddhist times, was as

numerous, perhaps even more so, than either the Aryans or Dravidians,

but of whose history we know even less than we do of the two others.

Ethnologists have not yet been even able to agree on a name by which to

call them. I have suggested Dasyus,[9] a slave people, as that is the

name by which the Aryans designated them when they found them there on

their first entrance into India, and subjected them to their sway.

Whoever they were, they seem to have been a people of a very inferior

intellectual capacity to either the Aryans or Dravidians, and it is by

no means clear that they could ever of themselves have risen to such a

status as either to form a great community capable of governing

themselves, and consequently having a history,[10] or whether they must

always have remained in the low and barbarous position in which we now

find some of their branches. When the Aryans first entered India they

seem to have found them occupying the whole valley of the Ganges--the

whole country in fact between the Vindhya and the Himalayan

Mountains.[11] At present they are only found in anything like purity in

the mountain ranges that bound that great plain. There they are known as

Bhîls, Coles, Sontals, Nagas, and other mountains tribes. But they

certainly form the lowest underlying stratum of the population over the

whole of the Gangetic plain.[12] So far as their affinities have been

ascertained, they are with the trans-Himalayan population, and it

either is that they entered India through the passes of that great

mountain range, or it might be more correct to say that the Thibetans

are a fragment of a great population that occupied both the northern and

southern slope of that great chain of hills at some very remote

pre-historic time.

Whoever they were, they were the people who, in remote times, were

apparently the worshippers of Trees and Serpents; but what interests us

more in them, and makes the inquiry into their history more desirable,

is that they were the people who first adopted Buddhism in India, and

they, or their congeners, are the only people who, in historic times, as

now, adhered, or still adhere to, that form of faith. No purely Aryan

people ever were, or ever could be, Buddhist, nor, so far as I know,

were any Dravidian community ever converted to that faith. But in

Bengal, in Ceylon, in Thibet, Burmah, Siam, and China, wherever a

Thibetan people exists, or a people allied to them, there Buddhism

flourished and now prevails. But in India the Dravidians resisted it in

the south, and a revival of Aryanism abolished it in the north.

Architecturally, there is no difficulty in defining the limits of the

Dasyu province: wherever a square tower-like temple exists with a

perpendicular base, but a curvilinear outline above, such as that shown

in the woodcut on the following page, there we may feel certain of the

existence, past or present, of a people of Dasyu extraction, retaining

their purity very nearly in the direct ratio to the number of these

temples found in the district. Were it not consequently for the

difficulty of introducing new names and obtaining acceptance to what is

unfamiliar, the proper names for the style prevailing in northern India

would be Dasyu style, instead of Indo-Aryan or Dasyu-Aryan which I have

felt constrained to adopt. No one can accuse the pure Aryans of

introducing this form in India, or of building temples at all, or of

worshipping images of Siva or Vishnu, with which these temples are

filled, and they consequently have little title to confer their name on

the style. The Aryans had, however, become so impure in blood before

these temples were erected, and were so mixed up with the Dasyus, and

had so influenced their religion and the arts, that it may be better to

retain a name which sounds familiar, and does not too sharply prejudge

the question. Be this as it may, one thing seems tolerably clear, that

the regions occupied by the Aryans in India were conterminous with those

of the Dasyus, or, in other words, that the Aryans conquered the whole

of the aboriginal or native tribes who occupied the plains of northern

India, and ruled over them to such an extent as materially to influence

their religion and their arts, and also very materially to modify even

their language. So much so, indeed, that after some four or five

thousand years of domination we should not be surprised if we have some

difficulty in recovering traces of the original population, and could

probably not do so, if some fragments of the people had not sought

refuge in the hills on the north and south of the great Gangetic plain,

and there have remained fossilised, or at least sufficiently permanent

for purposes of investigation.

[Illustration: Hindu Temple, Bancorah.]

SISUNAGA DYNASTY, B.C. 691 TO 325.

Leaving these, which must, for the present at least, be considered as

practically pre-historic times, we tread on surer ground when we

approach the period when Buddha was born, and devoted his life to rescue

man from sin and suffering. There seems very little reason for doubting

that he was born in the year 623, in the reign of Bimbasara, the fifth

king of this dynasty, and died B.C. 543, at the age of eighty years, in

the eighth year of Ajattasatru, the eighth king. New sources of

information are opening out so rapidly regarding these times, that there

seems little doubt we shall before long be able to recover a perfectly

authentic account of the political events of that period, and as perfect

a picture of the manners and the customs of those days. It is too true,

however, that those who wrote the biography of Buddha in subsequent

ages so overlaid the simple narrative of his life with fables and

absurdities, that it is now difficult to separate the wheat from the

chaff; but we have sculptures extending back to within three centuries

of his death, at which time we may fairly assume that a purer tradition

and correcter version of the Scriptures must have prevailed. From what

has recently occurred, we may hope to creep even further back than this,

and eventually to find early illustrations which will enable us to

exercise so sound a criticism on the books as to enable us to restore

the life of Buddha to such an extent, as to place it among the authentic

records of the benefactors of mankind.

Immense progress has been made during the last thirty or forty years in

investigating the origin of Buddhism, and the propagation of its

doctrines in India, and in communicating the knowledge so gained to the

public in Europe. Much, however, remains to be done before the story is

complete, and divested of all the absurdities which subsequent

commentators have heaped upon it; and more must yet be effected before

the public can be rendered familiar with what is so essentially novel to

them. Still, the leading events in the life of the founder of the

religion are simple, and sufficiently well ascertained for all practical

purposes.[13]

The founder of this religion was one of the last of a long line of

kings, known as the Solar dynasties, who, from a period shortly

subsequent to the advent of the Aryans into India, had held paramount

sway in Ayodhya--the modern Oude. About the 12th or 13th century B.C.

they were superseded by another race of much less purely Aryan blood,

known as the Lunar race, who transferred the seat of power to capitals

situated in the northern parts of the Doab. In consequence of this, the

lineal descendants of the Solar kings were reduced to a petty

principality at the foot of the Himalayas, where Sakya Muni was born

about 623 B.C. For twenty-nine years he enjoyed the pleasures, and

followed the occupations, usual to the men of his rank and position; but

at that age, becoming painfully impressed by the misery incident to

human existence, he determined to devote the rest of his life to an

attempt to alleviate it. For this purpose he forsook his parents and

wife, abandoned friends and all the advantages of his position, and, for

the following fifty-one years, devoted himself steadily to the task he

had set before himself. Years were spent in the meditation and

mortification necessary to fit himself for his mission; the rest of his

long life was devoted to wandering from city to city, teaching and

preaching, and doing everything that gentle means could effect to

disseminate the doctrines which he believed were to regenerate the

world, and take the sting out of human misery.

He died, or, in the phraseology of his followers, obtained Nirvana--was

absorbed into the deity--at Kusinara, in northern Behar, in the 80th

year of his age, 543 years[14] B.C.

With the information that is now fast accumulating around the subject,

there seems no great difficulty in understanding why the mission of

Sakya Muni was so successful as it proved to be. He was born at a time

when the purity of the Aryan races in India had become so deteriorated

by the constant influx of less pure tribes from the north and west, that

their power, and consequently their influence, was fast fading away. At

that time, too, it seems that the native races had, from long

familiarity with the Aryans, acquired such a degree of civilisation as

led them to desire something like equality with their masters, who were

probably always in a numerical minority in most parts of the valley of

the Ganges. In such a condition of things the preacher was sure of a

willing audience who proclaimed the abolition of caste, and taught that

all men, of whatever nation or degree, had an equal chance of reaching

happiness, and ultimately heaven, by the practice of virtue, and by that

only. The subject races--the Turanian Dasyus--hailed him as a deliverer,

and it was by them that the religion was adopted and proclaimed, and

that of the Aryan Brahmans was for a time obliterated, or at least

overshadowed and obscured.

It is by no means clear how far Buddha was successful in converting the

multitude to his doctrines during his lifetime. At his death, the first

synod was held at Rajagriha, and five hundred monks of a superior order,

it is said, were assembled there on that occasion,[15] and if so they

must have represented a great multitude. But the accounts of this, and

of the second convocation, held 100 years afterwards at Vaisali, on the

Gunduck, have not yet had the full light of recent investigation brought

to bear upon them. Indeed the whole annals of the Naga dynasty, from the

death of Buddha, B.C. 543, to the accession of Chandragupta, 325, are

about the least satisfactory of the period. Those of Ceylon were

purposely falsified in order to carry back the landing of Vyjya, the

first conqueror from Kalinga, to a period coincident with the date of

Buddha’s death, while a period apparently of sixty years at least

elapsed between the two events. All this may, however, be safely left to

future explorers. We have annals and coins,[16] and we may recover

inscriptions and sculptures belonging to this period, and, though it is

most improbable we shall recover any architectural remains, there are

evidently materials existing which, when utilised, may suffice for the

purpose.

The kings of this dynasty seem to have been considered as of a low

caste, and were not, consequently, in favour either with the Brahman or,

at that time, with the Buddhist; and no events which seem to have been

thought worthy of being remembered, except the second convocation, are

recorded as happening in their reigns, after the death of the great

Ascetic--or, at all events, of being recorded in such annals as we

possess.

MAURYA DYNASTY, B.C. 325 TO 188.

The case was widely different with the Maurya dynasty, which was

certainly one of the most brilliant, and is fortunately one of the best

known, of the ancient dynasties of India. The first king was