The Project Gutenberg EBook of Birds of the National Parks in Hawaii, by

William W Dunmire (1930-)

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and

most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms

of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at

www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll

have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using

this ebook.

Title: Birds of the National Parks in Hawaii

Author: William W Dunmire (1930-)

Release Date: May 1, 2019 [EBook #59398]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK BIRDS OF THE NATIONAL PARKS ***

Produced by Stephen Hutcheson and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE

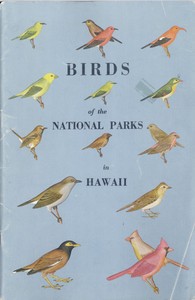

[Illustration: PUBLISHED IN COOPERATION WITH THE NATIONAL PARK

SERVICE]

HAWAII VOLCANOES NATIONAL PARK

HALEAKALA NATIONAL PARK

[Illustration: HAWAII NATURAL HISTORY ASSOCIATION]

copyright 1961

cover by Ronald L. Walker

(see center plate for identification)

BIRDS

_of the_

NATIONAL PARKS

_in_

HAWAII

by

William W. Dunmire

_Park Naturalist, Hawaii National Park_

Illustrated by Ronald L. Walker

_District Biologist, State Division of Fish & Game_

HAWAII NATURAL HISTORY ASSOCIATION

1961

[Illustration: _Trail Through Kipuka Puaulu (Bird Park)_]

_Table of Contents_

Page

Introduction 2

How the Birds Came 3

The Decline of Native Birds 4

Where to See the Birds 5

The National Parks 8

About This Booklet 8

The Birds

Petrels: Family Procellariidae 11

Tropic-birds: Family Phaëthontidae 11

Geese: Family Anatidae 13

Hawks: Family Accipitridae 15

Quails, Partridges, Pheasants: Family Phasianidae 15

Plovers, Turnstones: Family Charadriidae 19

Sandpipers: Family Scolopacidae 20

Terns: Family Laridae 20

Doves: Family Columbidae 21

Owls: Family Strigidae 22

Larks: Family Alaudidae 22

Babbling Thrushes: Family Timeliidae 23

Mockingbirds: Family Mimidae 24

Thrushes: Family Turdidae 25

Old World Flycatchers: Family Sylviidae 26

Starlings: Family Sturnidae 27

White-eyes: Family Zosteropidae 27

Hawaiian Honeycreepers: Family Drepaniidae 28

Weaver Finches: Family Ploceidae 32

Finches, etc.: Family Fringillidae 33

Other Birds 34

Index 35

INTRODUCTION

When the Hawaiian Islands were first studied by ornithologists in the

nineteenth century, they were a bird paradise. The forests abounded with

many of the most unusual birds known to the world—some with enormous

sickle-shaped bills, some resembling parrots, a goose that spent most of

its life on barren lava flows, a tiny flightless rail, and a sea bird

that nested within the vents of the active volcanoes. Most of these

island birds were found nowhere else in the world.

Today many of the original island species are extinct, while others are

barely managing to hold their own. With more and more land being cleared

for agriculture and homesites, virgin forests here are becoming scarce.

Thus, protected areas like Hawaii Volcanoes and Haleakala National Parks

take on great significance as reserves where the native birds will

continue to survive. If you wish to learn about Hawaiian birdlife, you

will certainly want to spend some time in Hawaii Volcanoes National Park

and visit Haleakala National Park on the island of Maui. This booklet is

meant to be an aid to your trips in the field.

[Illustration: _Fern jungle—Thurston Lava Tube trail_]

HOW THE BIRDS CAME

Geologically the Hawaiian Islands are considered to be fairly young,

probably no more than 20 million years old. The islands are also

extremely isolated from any other land masses; it is more than 2,000

miles to the nearest continent. Before any resident birdlife could exist

here, plants had to become established. Seeds arrived by various means

from distant lands, and one by one new kinds of plants began to grow on

the volcanoes—at first only a few primitive types could get a foothold

on the barren lava, but in time those early plants decayed and combined

with the basalt rock to produce a soil that could support a complex

vegetation.

Endemics

We have no way of knowing what kind of land bird was the first to take

up residence here, for that early species has certainly been greatly

altered through the workings of evolution. In fact today nearly all the

resident native birds are types that are now found nowhere else in the

world. Birds such as these are called _endemic_; they have undergone

gradual change over the millennia to become completely new forms,

different from any birds found elsewhere.

Many of Hawaii’s endemic species belong to the Hawaiian honeycreeper

family (Drepaniidae) and are thought to have evolved from a single bird

prototype that possibly arrived here from Central or South America.

Explosive bursts of evolutionary change followed, and the resulting new

forms did not much resemble each other. Present day park representatives

of the Hawaiian honeycreepers include the apapane, iiwi, and amakihi.

Besides the Hawaiian honeycreeper stock several other early migrants

made their residence in Hawaii and evolved into endemic forms. In the

park they include a Hawaiian race of the (North American) short-eared

owl, the io (a hawk), the nene (a goose), the omao (a thrush), and the

elepaio (an Old World flycatcher).

Migrants and Sea Birds

While the endemic species have acquired full residence on the islands,

other birds live here for only part of the year, usually returning to

the north during summer to breed. In the park the best known of these

migrants is the American golden plover which spends almost 10 months of

the year in Hawaii and only 2 months on its travels to the Aleutian

Islands.

Migration patterns for certain of the sea birds are virtually unknown.

Some, like the white-tailed tropic-bird, may remain near the islands

throughout the year, while others, such as the dark-rumped petrel,

migrate inland only during their breeding season.

Exotics

The most recent additions to Hawaii’s avifauna are birds brought in

since 1855 by man. There are various reasons for the introductions; the

mynah, for example, was brought here from India in 1865 to combat the

army worm and other insect pests. Perhaps most of the exotics were

introduced because people wanted to see birds that reminded them of

their former homes. Birds like the cardinal from the eastern United

States and the white-eye from Japan are in this category. For years the

Hui Manu, a local bird club, was active in releasing new birds on the

islands. Game birds constitute another type of introduction. The first

to arrive was the California quail more than a hundred years ago.

Pheasants and chukars among others have also become established in the

park from importations.

THE DECLINE OF NATIVE BIRDS

In no area in the world have native birds fared more poorly than in

Hawaii during the past century. The causes of the decimation of numbers

and species are probably multiple; certainly no single factor alone can

be cited. Possibly some of the most specialized forms had already begun

a decline in numbers before the arrival of Western man. It is unlikely

that feather gathering for leis as practiced by the ancient Hawaiians

had much to do with the decline. On the other hand, the clearing of

land, which began early in the 1800’s, must have had a devastating

effect on those birds that had become so specialized—they simply were

forced into new environments and were unable to adapt. The introduction

of new plants, especially grasses, and the establishment of feral

mammals (goats, sheep, and pigs), and insects played a subtle but

possibly even more destructive role in altering the over-all

environment.

Introduction of exotic birds must have been the final blow to many of

the native species. Unfortunately until recently there was no adequate

control over importing and releasing new birds in Hawaii. The delicate

balance of nature was rudely upset when some of the more aggressive

exotic birds were released indiscriminately on the islands. Exotic birds

such as the white-eye became so plentiful that direct competition for

food with the natives must have occurred. Furthermore, bird diseases new

to Hawaii, such as avian malaria (probably brought to the islands with

some introduced bird from the Orient), would have been a great killer.

With a few exceptions, however, it does seem that the remaining Hawaiian

native birds are now holding their own.

WHERE TO SEE THE BIRDS

You will probably be amazed at the extremes of climate in Hawaii,

especially on Kilauea Volcano. This is one of the rare places in the

world where you can walk a few hundred yards from an area of heavy

rainfall to one of striking dryness. The change is due to prevailing

trade winds which force moisture laden clouds up over the mountain

masses from the northeast, then allow the clouds to dissipate on the

leeward side of the mountains. By taking the Crater Rim drive at

Kilauea, you will pass through lush fern jungle on one side of the

crater and barren desert on the other.

Birds are very sensitive to these differences in climate. Most of the

species you find at Thurston Lava Tube will never be seen at Halemaumau,

less than 3 miles away. The same thing is true at Haleakala, although

less dramatically so. To help you locate the most rewarding sites for

bird study in the park, here are a few suggestions:

Kilauea-Mauna Loa

_Thurston Lava Tube._ This is the heart of Hawaii’s tree-fern jungle and

an excellent habitat for several native species, such as the apapane,

iiwi, and amakihi. Spend a few moments looking for these at the exhibit

overlook, then take the quarter-mile loop path that leads through the

lava tube. On the other side of the lava tube parking area a trail

descends into Kilauea Iki, the site of the 1959 eruption. This

delightful walk also passes through fern jungle. Be on the lookout for

the io (Hawaiian hawk) in Kilauea Iki.

[Illustration: _Grass slopes on the Mauna Loa Strip_]

_Halemaumau._ A most unlikely place for birds; however, there are almost

always a few white-tailed tropic-birds soaring within the pit.

_Kipuka Puaulu._ A popular name for this area is “Bird Park” and for

good reason, for this kipuka, a hundred acre island of well developed

vegetation surrounded by a recent lava flow, harbors 11 or more species.

The commonest here are the white-eye, red-billed leiothrix, and house

finch—all exotics. When the ohia trees are in bloom, and usually there

are at least a few, large numbers of iiwis and apapanes are attracted to

the kipuka. Other interesting birds often seen here are the elepaio,

Japanese blue pheasant, and cardinal.

_Mauna Loa Strip._ More kinds of birds (18) have been recorded from the

koa parkland along the Mauna Loa Strip road than from any other locality

in the park, but you are not likely to see large numbers in any one

place along the strip. The road ascends the lower slopes of Mauna Loa

from 4,000 feet at Kipuka Puaulu to 6,663 feet. Several introduced game

birds—Japanese blue pheasant, California quail, and chukar—may be

flushed as you drive up the road. Skylarks and house finches are fairly

common along the grassy flats, and you are almost sure to see an amakihi

in the koa grove at the end of the road. If you are lucky you might be

rewarded with a glimpse of a nene somewhere on these upper slopes.

Haleakala

_Hosmer Grove and Paliku._ These two localities are about the only

densely wooded areas in Haleakala National Park and both attract a

variety of birdlife. The apapane, iiwi, and amakihi as well as several

exotic birds can be seen at either place. A delightful self-guiding

nature trail that identifies many of the plants and trees winds through

the Hosmer Grove.

_Road to Haleakala Summit._ As you drive up to the Observatory from Park

Headquarters you will probably be surprised at the number of ring-necked

pheasants and chukars that flush along the road. Golden plovers and

skylarks are also plentiful, and mockingbirds may be seen occasionally.

[Illustration: _Visitor cabin at Paliku, Haleakala_]

THE NATIONAL PARKS

Hawaii Volcanoes National Park and Haleakala National Park are two of

more than 180 different areas administered by the National Park Service

for your enjoyment. The two areas, Haleakala on Maui and Kilauea-Mauna

Loa on Hawaii, were set aside, as one park, by Congress in 1916 mainly

because of the three great volcanoes. In July 1961 Haleakala became a

separate national park. In recent years the unique flora and fauna found

in the parks have become an increasingly important part of the park

story. Thus you will find several interesting exhibits at the Kilauea

headquarters museum dealing with the ecology of the park with emphasis

on the birdlife.

One of the guiding principles for any national park is that all native

species of plants and animals are rigidly protected. In places like

Hawaii, where so much of the land has been altered through clearing and

planting, the park becomes a particularly important sanctuary for birds

and other animals. Please help do your share in protecting this area by

observing park regulations.

ABOUT THIS BOOKLET

The purpose of this booklet is to help anyone who cares to learn about

the birdlife of the national parks in Hawaii. Many of you, here in

Hawaii for the first time, will not recognize most of our birds;

however, the species are so few (32 described here) that it will not be

too hard to narrow your identification to the correct one. The little

perching birds are likely to give the most trouble, and the commonest of

these are shown on the color plate. You will probably want to refer to

the plate first when identifying a small bird. Descriptions in the text

refer to similar species also, so if you see a bird that appears

somewhat, but not exactly, like one of the illustrations, look up the

illustrated species in the text for clues.

Hawaiian names, when known, are used as the common name for each bird,

except for species that range elsewhere (e.g., all the sea birds and

introduced birds). The _A.O.U. Checklist of North American Birds_ has

been used as the authority of nomenclature wherever applicable,

otherwise the _Checklist and Summary of Hawaiian Birds_ by E. H. Bryan,

Jr., has been followed. For every description, length from the tip of

the bill to the end of the tail is given in inches. The stated

distributions are for the park only and they emphasize accessible places

that you are most likely to visit.

The serious bird student will want to have books that include Hawaiian

birds outside the park. The latest edition of Peterson’s _A Field Guide

to Western Birds_ includes a section on Hawaii and will prove

invaluable.

In preparing the text for this booklet frequent reference was made to

George C. Munro, 1944, _Birds of Hawaii_ and Hawaii Audubon Society,

1959, _Hawaiian Birds_. The most important current references for the

Hawaiian honeycreeper group are Dean Amadon’s (1950) monograph, _The

Hawaiian Honeycreepers_ and _Annual Cycle_, _Environment and Evolution

in the Hawaiian Honeycreepers_ by Paul H. Baldwin (1953). Baldwin, a

former Assistant to the Superintendent of Hawaii National Park, has

authored several other important papers on birdlife here. _The Game

Birds in Hawaii_ by Charles W. and Elizabeth R. Schwartz is an

invaluable reference on gamebirds.

The author wishes to acknowledge helpful suggestions made by E. H.

Bryan, Jr., of the Bernice P. Bishop Museum; Robert L. Barrel, Robert W.

Carpenter, and Robert T. Haugen of Hawaii National Park; and Ronald L.

Walker and David H. Woodside of the State Division of Fish and Game. The

Bishop Museum generously loaned study specimens for the drawings.

The black and white and color drawings are by Ronald L. Walker, and all

photographs are by the author except where noted.

[Illustration: _Haleakala Crater, breeding grounds for the

dark-rumped petrel_]

[Illustration: PHOTO BY FRANK RICHARDSON

_Dark-rumped petrel_]

DARK-RUMPED PETREL _Pterodroma phaeopygia_

(Hawaiian name—uau)

DESCRIPTION: 15″. Underparts, forehead, and cheeks, white; back, upper

wings, and upper tail, dark. The crown is black.

PARK DISTRIBUTION: This petrel is a sea bird that nests in the mountains

of the Hawaiian group; it is the nesting birds that may be seen or heard

within the park between May and November. Kilauea—Status unknown; the

cliffs of Kilauea Crater may be used for nesting. Haleakala—Many birds

nest in the walls of the crater. The cliffs behind Kapalaoa and Holua

Cabins are the best places to hear them at night.

VOICE: As the birds fly overhead seeking their burrows after dusk, the

air is filled with their strange calls, some of which sound like the

barking of a small dog. A common pattern of notes is _oooo-wéh, ooo-wéh,

oo-wéh, oo-wéh_, etc., with the first notes drawn out and the last run

together in rapid succession.

Dark-rumped Petrels spend most of their life at sea, but in April and

May they begin their nightly flights inland to burrows they have

established high on the cliffs of Hawaiian volcanoes. A single egg is

laid near the end of the horizontal cavity that may be more than 6 feet

deep in the rocks. For the next 6 months the adults will fly in from the

ocean each night to tend the nest, arriving about an hour after sundown.

It is while they are circling in search of the burrows that you can hear

their mysterious barking sounds. The calling may continue for 2 hours or

more. Imagine the problems that each petrel must face trying to find its

own burrow 20 miles from the ocean on a foggy, moonless night—perhaps

the continuous calling back and forth helps orient it. The adults return

to the ocean before sunrise.

In the early days nesting birds were common on all the main Hawaiian

Islands; however, for a time it was feared that they were becoming

extinct. Hawaiians used to dig out the downy young petrels for food, and

introduced mongooses and cats also took a heavy toll, especially where

nests were at lower elevations. Now, with known breeding colonies high

on Haleakala and Mauna Kea and probably on Mauna Loa and Kilauea, the

future of this interesting species seems assured.

WHITE-TAILED TROPIC-BIRD _Phaëthon lepturus_

(Hawaiian name—koae)

DESCRIPTION: 30″-32″. Unmistakable as a large white bird with two

fantastically long tail plumes, soaring around rocky cliffs such as in

Halemaumau. There is some black on the upper wings and around the face.

PARK DISTRIBUTION: Kilauea—Uncommon, except locally. There are nearly

always a few birds soaring in Halemaumau, around the pit craters in the

Kau Desert, and near Hilina Pali. They are occasionally seen along the

coast. Haleakala—Some can usually be seen in the crater, especially

around the ruggedest cliffs such as behind Holua and Paliku Cabins.

VOICE: High pitched rasping cries.

Halemaumau—What a strange place for a sea bird! Yet these fish-eating

birds have nested in the Kilauea area for as long as we have records. In

recent years Halemaumau has been their favorite haunt, except when

volcano fumes drive them away, such as during the time when heavy

sulphur gasses filled the pit in June 1960. When Halemaumau erupts the

birds may become trapped by rapidly rising hot gas; in 1952 several of

them perished, falling into the molten lava below. For a meal the

Halemaumau birds must make at least a 10-mile flight to the ocean.

[Illustration: EXHIBIT AT THE PARK MUSEUM

_White-tailed tropic-bird_]

[Illustration: _Nene—the native Hawaiian goose_]

NENE _Branta sandvicensis_

(also Hawaiian goose)

DESCRIPTION: 23″-28″. The only ducklike bird apt to be seen in the park.

A medium sized goose with striking head and neck markings. The face,

crown, and top of the neck are black, the throat and neck sides are

cream colored, and the remainder of the body is mottled and dark.

PARK DISTRIBUTION: Formerly abundant in Hawaii and probably Maui. Now

extinct on Maui, while a few wild birds remain on Hawaii.

Kilauea—Occasionally seen on the slopes of Mauna Loa usually between

6,000 and 7,500 feet.

VOICE: Various thin, creaky notes. Often gives a high-pitched honking in

flight.

Because of recent studies, the habits of the nene are probably better

understood than those of any other native Hawaiian bird. The most

amazing thing about their life is the way they have forsaken water in

favor of rough, clinkery lava. All other ducks and geese rear their

young partly in water, but today the breeding grounds for the nene, high

on the barren slopes of Mauna Loa, are far from the nearest open water.

Here during the winter months the geese raise their broods of two to

five young. Berries, herbs, and grass growing in kipukas (islands of

vegetation surrounded by more recent lava flows) comprise the diet. At

present the nene is one of the rarest birds in the world and has been

near extinction in recent years.

The story of the nene’s decline is a sad one but it may yet have a happy

ending. Early visitors to the islands described the large flocks of nene

geese in the interior of Hawaii, but by 1900 a great decline in numbers

had occurred and in 1940 the entire population was estimated at 30 to 50

wild birds. Clearing of the land, introduction of such exotic mammals as

rats, pigs, dogs, and mongooses, and man himself through hunting—all

must share the blame for the nene decimation. Happily, the State of

Hawaii has taken vigorous recognition of this situation and a

restoration program was begun in 1949. The plan is to study the

remaining wild birds to learn how the decimating factors may be

controlled. Also nene raised in captivity have been released on Mauna

Loa to intermix with the wild flocks, and it is hoped that some day

visitors to Hawaii will again be assured of seeing these wonderful

geese.

[Illustration: PHOTO BY GEORGE C. RUHLE

_Nene Nest_]

IO _Buteo solitarius_

(also Hawaiian hawk)

DESCRIPTION: 16″-18″. The only hawklike bird to be seen on the islands,

except for accidental migrants. This small _Buteo_ has both light and

dark color phases. Can be distinguished from the Pueo, Hawaii’s diurnal

owl, by a smaller head and more soaring flight.

PARK DISTRIBUTION: Found only on the island of Hawaii.

Kilauea—Occasional throughout the park. Individuals are often seen

soaring around the forested craters such as Kilauea Iki and Makaopuhi,

or in the more open areas such as along the Mauna Loa Strip road.

VOICE: A medium-pitched, but fairly soft, scream.

The io is certainly one of the rarest hawks in the world, as its range

is limited to the island of Hawaii, and even here it is not common. It

feeds on rats, mice, and large insects and spiders, and occasionally

will catch birds, but today birds comprise a minor part of the diet. It

tends to be tamer than mainland hawks, perhaps because it has not been

harassed as much in recent years, and sometimes you can approach a

perched io quite closely. Because of its rodent diet, the io is a very

beneficial bird to Hawaii.

[Illustration: _California quail (male and female)_]

CALIFORNIA QUAIL _Lophortyx californicus_

DESCRIPTION: 9½″-10½″. The distinctive _curved head plume_ identifies

this plump quail. Males have a black and white face pattern beneath the

brown crown, while females are duller and lack the striking facial

pattern. The bill is short and black.

PARK DISTRIBUTION: Introduced from California before 1855 to all major

islands. Kilauea—Moderately common along the Mauna Loa Strip and south

and west of Kilauea Crater, for example Kipuka Nene. Haleakala—Fairly

common on slopes outside the crater up to about 8,000 feet.

VOICE: Both sexes issue a three noted _ka-kér-ko_, also clucking notes

_tek-tek_, etc.

Although the California quail has been in the islands for a long time,

it has not spread much in the park, probably because there is no

available open water. In this situation the birds must rely on dewfall,

berries, or succulent vegetation for their moisture requirements. They

shun heavy forests and do best where small grassy openings are

interspersed with dense brush thickets.

CHUKAR _Alectoris graeca_

DESCRIPTION: 15″. A heavy ground dwelling partridge, brownish with

buffy, black, and rusty markings. A black band extends through each eye

and joins the lower throat. Distinguished from the quail by lighter

color, lack of a head plume, and a red-orange bill.

[Illustration: _Chukar_]

PARK DISTRIBUTION: Introduced on Hawaii in 1949, on Maui in 1953.

Kilauea—Occasional on the slopes of Mauna Loa, descending as far as the

rim of Kilauea Crater. Haleakala—Common in open lava slopes inside and

out of the crater but especially along the drive to the summit.

VOICE: Chickenlike cackles and clucks, sometimes quite loud.

They are well camouflaged to blend with Hawaii’s gray lava and are not

usually seen until one or more flushes from an open or even bare slope.

Then they will fly downslope, sometimes for hundreds of yards, land, and

again merge invisibly with the somber background.

During the breeding season in late spring and summer the birds pair up;

at other times of the year you may encounter coveys of a dozen or more.

RING-NECKED PHEASANT _Phasianus colchicus torquatus_

(also Chinese pheasant)

DESCRIPTION: Male 33″-36″; female 20″. _Male_: A rich chestnut-brown

bird with a conspicuous _white collar_ at the base of a dark green neck,

and an extremely long pointed tail. Hybridizes freely with the Japanese

blue pheasant, producing various combinations of ring-necked and blue

plumage. _Female_: Dull brown with a shorter tail than the male, similar

to the Japanese blue hen.

[Illustration: _Ring-necked pheasant cock_]

PARK DISTRIBUTION: Introduced from China about 1865, now widely

distributed on all main islands. Kilauea—Pure ring-necks are quite rare

but Japanese blue hybrids are not uncommon in grassy openings,

especially along the Mauna Loa Strip road. Haleakala—One of the most

common birds of the park, both inside and out of the crater.

VOICE: The cocks crow throughout the breeding season (January-July) with

a violent staccato _koor-káck_.

Optimum pheasant habitat is large open grassy areas interspersed with

brush cover, and since this condition prevails on the slopes of

Haleakala and along the Mauna Loa Strip road, these birds are found in

both sections of the park. Your first view of one will likely be when it

flushes out with a great flurry of wingbeats alongside a road or trail

in these grasslands. Family broods with as many as 10 chicks may be seen

from April through August.

JAPANESE BLUE PHEASANT _Phasianus colchicus versicolor_

(also versicolor or green pheasant)

DESCRIPTION: Male about 27″, female 20″. _Male_: Has a blue-green back,

iridescent green or purple breast, and long tail feathers. Appears

darker than the ring-necked pheasant and lacks the white collar.

_Female_: Brownish birds with long tails, indistinguishable from the

ring-necked hen.

PARK DISTRIBUTION: Introduced from Japan prior to 1900. Has lost its

identity on most islands due to hybridization with the ring-neck.

Kilauea—The park includes perhaps the best habitat in the islands for

this species. Pure Japanese blue males are common along the Mauna Loa

Strip road and occasional on the Chain of Craters road or the Crater Rim

drive and to the west. Hybrids will also be seen. Haleakala—Nearly all

are ring-necked pheasants here.

VOICE: The cock-crow is similar to that of the ring-neck, but somewhat

higher in pitch.

This species has adapted to the moist open-forest and grassland, while

the ring-neck prefers drier areas. Blues seem to have established a

niche on the southern slopes of Mauna Loa between 4,000 and 7,000 feet

elevation where mists are frequent, sometimes for days at a time.

KEY TO PLATE

AMAKIHI APAPANE IIWI

(male) (immature and adult)

OU WHITE-EYE RED-BILLED LEIOTHRIX

(male)

ELEPAIO RICEBIRD HOUSE FINCH

(female and male)

OMAO SKYLARK

MYNAH CARDINAL

(female and male)

[Illustration: Plate]

[Illustration: _American golden plover in winter plumage_]

AMERICAN GOLDEN PLOVER _Pluvialis dominica_

(Hawaiian name—kolea)

DESCRIPTION: 10″-11″. A medium sized shore bird with a straight,

inch-long bill. _Winter plumage_—mottled brown spotted with gold; buffy

breast. _Summer plumage_—striking pattern; back spotted with gold, black

undersides, and a white band over the forehead and down the sides of the

neck and breast. Plovers don their summer colors in April or May before

migration and may still retain them when they return in early August.

The only shore bird likely to be seen in the interior of either park.

PARK DISTRIBUTION: Winter migrant to the islands. Kilauea—Fairly common

locally from August to June. To be seen around Park Headquarters and on

the west side of Kilauea Crater or along the Mauna Loa Strip.

Haleakala—Common from August to June in open areas both inside and out

of the crater.

VOICE: A clear whistle _queep_, or _quee-leép_, etc., usually uttered as

the bird is flushed.

Like other migrants to Hawaii, golden plovers make a 2,000-mile (one

way) flight to and from their breeding grounds in Alaska or Siberia each

year. The trip requires about 48 hours, spent mostly over the open

ocean. When they arrive in Hawaii in the fall, individuals seem to

establish remarkably small territories—one bird may live during its

entire stay here in an area not much bigger than a large lawn. Here they

will feed on insects and berries until it is time for the annual

migration to the north.

RUDDY TURNSTONE _Arenaria interpres_

(Hawaiian name—akekeke)

DESCRIPTION: 9″. A chunky, medium sized shore bird with flashy black,

white, and russet-red markings and short orange legs. The contrasty

black and white pattern shows best in flight.

PARK DISTRIBUTION: Winter migrant to islands. Kilauea—Except for summer,

when they have migrated to Alaska, flocks are often found at rocky beach

areas around Halape, but they are uncommon elsewhere along the rugged

coast within park boundaries. Large flocks were formerly recorded inland

as far as Kilauea Crater. Haleakala—Absent from the park.

VOICE: A rapidly repeated _chut-a-chut_.

A flock of 8 or 10 turnstones will behave almost as though it was

controlled by one mind: in flight they dip and turn precisely together;

when they land it is a simultaneous action. The name turnstone comes

from their habit of flipping over small rocks with their bills to get at

the insects and other lower forms of life beneath.

WANDERING TATTLER _Heteroscelus incanum_

(Hawaiian name—ulili)

DESCRIPTION: 11″. A large sandpiper with _uniformly dark gray_ upper

parts and a long (1½ inches) straight bill. The belly is lighter, and

there is an indistinct white line over the eye. The long legs and the

feet are yellow.

PARK DISTRIBUTION: Winter migrant to islands. Kilauea—Uncommon along the

southern rocky shoreline. Absent in summer when it migrates to Alaska.

Haleakala—Absent from the park.

VOICE: A high clear _whee-we-we-we_ usually uttered as the bird takes

flight.

Individuals feed on crabs and other marine life among the rocks. They

never appear inland in the park.

WHITE-CAPPED NODDY _Anoüs tenuirostris_

(Hawaiian name—noio)

DESCRIPTION: 14″. A dark gray tern restricted to the rocky coastline.

The forehead and crown are lighter gray than the rest of the body.

PARK DISTRIBUTION: The only common bird to be seen flying just off

shore. In the park, restricted to the coastline of the Kilauea Section.

Look for these along the ocean at the Kalapana end of the park. They

flutter over the water picking up small fish, but usually they stay

close to shore. The noddies nest in sea cliffs and caves in this area.

SPOTTED DOVE _Streptopelia chinensis_

(also laceneck or Chinese dove)

DESCRIPTION: 12″. A gray-brown dove with a long rounded tail showing

white in the corners, and a broad _collar of black with white spots_ on

the neck.

PARK DISTRIBUTION: Introduced before 1900; now common below 4,000 feet

on all islands. Kilauea—Fairly common around the crater and at lower

elevations such as on the Chain of Craters and Hilina Pali roads.

Haleakala—Absent from the park.

VOICE: Typical dove-like coos; often _coo-coó-coo_.

Like the barred dove, this species does not much penetrate the native

rain forest, but rather seems restricted to areas where man has altered

the vegetation. Both species feed on seeds and some fruit.

[Illustration: _Spotted dove—Barred dove_]

BARRED DOVE _Geopelia striata_

DESCRIPTION: 8″-9″. Much smaller than the spotted dove and lacks the

lacy white neck. Has white outer tail feathers.

PARK DISTRIBUTION: Introduced to the islands in 1922; still spreading on

the island of Hawaii since its arrival here in 1935 from Asia.

Kilauea—Rare—at elevations below 3,000 feet. Haleakala—Absent from the

park.

VOICE: A rapid ringing phrase, higher pitched and faster than for the

spotted dove, often _wheeédle-de-wer_.

The range for this dove on Hawaii is continuing to increase. It is now

abundant along the Kona coast and has spread in both directions around

the island. Look for it within the park on the Hilina Pali road or on

the Kalapana road.

PUEO _Asio flammeus_

(also Hawaiian short-eared owl)

DESCRIPTION: 14″-15″. A medium-sized owl of buffy brown color and with

small ear tufts. In flight it appears big-headed and neckless compared

to the io.

PARK DISTRIBUTION: Kilauea—Occasional around the crater and in grassy

areas on the Mauna Loa Strip. Haleakala—Occasional near meadows inside

the crater such as at Paliku; also on the lower slopes, especially just

below Park Headquarters. They are frequently seen on the drive up to the

park.

VOICE: Rarely heard muffled barking sounds.

You may be surprised to see an owl soaring hawklike over grassy openings

in full daylight. However, this Hawaiian race of the mainland

short-eared owl is often diurnal. It will hover over one spot until a

mouse or rat ventures out into the open, then with a swoop the pueo

captures its meal.

SKYLARK _Alauda arvensis_

[Illustration: SKYLARK]

DESCRIPTION: 7″. A nondescript buffy, streaked bird with _white outer

tail feathers_ found only in open country. The head may appear crested.

PARK DISTRIBUTION: Introduced early to most of the islands.

Kilauea—Fairly common in open grassy places, for example on the floor of

Kilauea Crater or along the Mauna Loa Strip. Haleakala—Fairly common

both inside and out of the crater.

VOICE: Look to the sky when you hear an exceedingly long, high-pitched

rolling song. The skylark sings while on the wing and its beautiful

music may last for a minute or longer.

Certainly the most remarkable thing about this bird is its song—which it

delivers while hovering sometimes hundreds of feet in the air. Just when

you think that the lofty music must end, a skylark will change to a new

series of phrases and keep this up for another minute or so. Skylarks

feed and nest on the ground. Nests attributed to skylarks made entirely

of “Pele’s hair” have been found in the Kilauea area. “Pele’s hair” is

spun volcanic glass formed during an eruption—a strange material indeed

for the construction of a bird’s nest.

CHINESE THRUSH _Trochalopterum canorum_

(also spectacled thrush)

DESCRIPTION: 9″. In the dense wet forests a large, reddish-brown bird

with _broad white “eye spectacles”_ can only be this species. The white

band around each eye extends backward to the ear. You will probably hear

this bird before seeing it.

PARK DISTRIBUTION: Introduced at the turn of the century. Now on all

major islands. Kilauea—Occasional in the wet ohia forest such as around

Park Headquarters. Haleakala—Absent from the park.

VOICE: A mockingbird-like series of sustained musical and harsh notes

that carries for a great distance. The rich phrases may be repeated

several times before a new pattern is given.

These secretive birds seem to make a vertical migration to Kilauea from

the east each summer. They are rarely observed in the park during winter

months, but that may be due to their lack of song in the non-breeding

season. In summer you will probably hear several before seeing even one,

as they are wary and keep to the underbrush, moving about very little.

RED-BILLED LEIOTHRIX _Leiothrix lutea_

(also Japanese hill robin or Peking nightingale)

[Illustration: RED-BILLED LEIOTHRIX]

DESCRIPTION: 5½″. One of the easiest to identify: An olive-green bird

with contrasting red and yellow markings and a _bright red-orange bill_.

The back is olive-green, throat lemon-yellow shading to red-orange in

the breast, and the wing varied with yellow, orange, crimson, and black.

Immatures are not as bright, but have the same general markings.

PARK DISTRIBUTION: Introduced to the islands from Asia mainly in the

twenties. Kilauea—Very common throughout vegetated areas.

Haleakala—Fairly common in areas of dense vegetation such as Paliku.

VOICE: No wonder these birds are sometimes called “robins”, for their

robinlike warbled song fills the air in spring and summer. If you

approach they will often begin their excited noisy call notes, a rapid

_bzzt-bzzt-bzzt_, etc., which will usually continue for some time as the

birds nervously flit about the underbrush. Another common note, usually

heard from a distance, is a sharp _wheek-wheek-wheek_ made up of 3-8

notes.

The leiothrix is strictly a bird of the undergrowth and you are likely

to find it wherever there is plenty of bush cover in moist forested

areas. Mamake, a Hawaiian nettle, is one of its favorite haunts. If one

bird is seen, there are probably several others nearby, and flocks of a

dozen or more are common in fall and winter. Fruit, seeds, and insects

comprise the food.

These birds have strange migration habits. In the fall and early winter

large flocks may suddenly appear at the summit of Haleakala where they

stay a short time and then return to lower areas. On Hawaii flocks have

been recorded at above 13,000 feet on Mauna Loa during this season, but

they are reduced by deaths caused by exposure and starvation on the

barren slopes if they do not descend soon.

Although today the leiothrix is one of the best loved birds on the

islands, its introduction here may have been unfortunate. It is known to

be a carrier of bird malaria, a disease that has probably contributed to

the continuing decline of native Hawaiian honeycreepers.

MOCKINGBIRD _Mimus polyglottos_

DESCRIPTION: 10″-11″. A slender, gray and white bird with _large white

wing patches_ and white outer tail feathers.

PARK DISTRIBUTION: Introduced since 1928 on Oahu and Maui.

Kilauea—Birds, apparently migrants from Maui, were seen in the northern

part of the island in 1959; however, none have yet reached the park

(1961). Haleakala—Occasional on slopes below the summit; rare inside

Haleakala Crater. Probably still increasing its range within the park.

VOICE: The song is a brilliant series of phrases often repeated like the

Chinese thrush but more varied. One note is an emphatic _thack_.

You are most likely to see mockingbirds along the lower slopes of

Haleakala during your drive up to the crater. Park Headquarters is about

the upper limit for these birds on Maui. The food consists of insects,

fruit, and occasionally greens.

OMAO _Phaeornis obscura_

(also Hawaiian thrush)

[Illustration: OMAO]

DESCRIPTION: 7″. Usually heard first, then seen if you are patient, for

it often remains motionless. A medium sized gray-brown thrush with no

distinct markings. Only similar species is the Chinese thrush which is

larger, more reddish brown, and has white markings around the eye.

PARK DISTRIBUTION: Kilauea—Moderately common in the wet ohia forest,

especially along the Crater Rim Trail between Park Headquarters and

Thurston Lava Tube. Uncommon on lava flows between 7,000 and 9,200 feet

elevation—to be seen along the Mauna Loa trail. Haleakala—Absent from

Maui.

VOICE: Any one of several buzzing notes, a medium pitched _eéau_, or

_prueeé_, or a low throaty _whuaaá_ are likely to be heard before the

song. These notes may be interspersed and are often repeated many times

with a few seconds interval. The song is a rapid, erratic whistled

phrase, having the loud fluty quality of other thrushes.

This strange thrush lives in two contrasting habitats within Hawaii

Volcanoes National Park. In the dense forest you will usually find it

singing from its perch part way up an ohia or other tree. But there may

be no trees in sight at its other locality which is among the barren

lava flows on Mauna Loa. However, there will always be berry bushes

nearby—ohelo, pukeawe, or kukaenene; and insects also comprise a part of

the diet. The lava flow birds establish day-time roosts on the higher

rocks and remain at these sites for long periods, judging from the

accumulation of droppings. Old perch sites stand out clearly on a flow,

for a yellow-green lichen colors the top of whatever rocks have been

plastered with omao droppings.

[Illustration: _Ohelo—favorite food of the omao_]

The nesting sites for these birds have remained an enigma until

recently. Now it is known that birds living on the flows will build

their nests on ledges within deep horizontal lava cracks, especially in

collapsed lava tubes, while the forest birds are said to nest in trees.

ELEPAIO _Chasiempsis sandwichensis_

[Illustration: ELEPAIO]

DESCRIPTION: 5½″. A brownish flycatcher with variegated black, white,

and gray markings. The dark bill is short (½ inch) and nearly straight.

The female has less black on the breast and throat, while immatures,

generally more brown, have a reddish instead of a white ruff around the

vent. Its friendly wrenlike actions combined with the above make it

unmistakable.

PARK DISTRIBUTION: Kilauea—Common in the more heavily vegetated areas

around Kilauea Crater and to the east. Look for it at Kipuka Puaulu.

Haleakala—Absent from Maui.

VOICE: A variety of short songs or calls. One is like a “wolf whistle”,

a clear _wheé-oo_ (or _elepaí-o_). Another is a nasal _yeékik_. A single

_wheek_ as well as short nasal chirps are also common.

The elepaio is probably the friendliest of our native birds. It is

easily overlooked, since it usually remains fairly quiet when you first

approach, but if you pause for a few moments in the wet fern jungle, one

or more of these birds are likely to appear. They seem very inquisitive

as they hop about in the low underbrush, often within a few feet of an

observer, and they cock their tails high whenever they alight. Like the

omao these birds often push their wings forward with a rapid shivering

motion when confronted by people, probably a type of aggressive action.

Being a member of the Old World flycatcher family, the elepaio is

adapted to an insect diet which it gleans from the tree tops to the

ground, but mostly in the understory. It often feeds like a creeper,

carefully working up or down the trunk of an ohia in search of insect

life. There seem to be no seasonal movements; individuals or family

groups of two to four birds apparently remain in the same general area

throughout the year.

MYNAH _Acridotheres tristis_

[Illustration: MYNAH]

DESCRIPTION: 9″. No other bird like it. Black, brown, and white with

yellow bill, feet, and skin around the eye; above all noisy. Large white

wing patches are conspicuous in flight.

PARK DISTRIBUTION: Introduced from India in 1865. Kilauea—Common at Park

Headquarters, around other human habitations, and to the south

especially around Hilina Pali. Occasional in the Kau Desert. Haleakala—A

few live around the Park Headquarters area in the summer months but they

descend to lower elevations in winter.

VOICE: A raucous mixture of squawks, mews, and chirrs not likely to be

mistaken for any other bird.

For a bird that prefers to live around human habitations, the mynah is

extremely wary of people—probably with good reason, for among the

imported birds the mynah has never been particularly well loved. Yet it

is at least partly beneficial since it often feeds on agricultural

insect pests. “Mynah bird” has become a favorite Hawaiian expression for

anyone who chatters endlessly.

WHITE-EYE _Zosterops palpibrosus_

(also mejiro)

[Illustration: WHITE-EYE]

DESCRIPTION: 4½″. A tiny yellow-green bird with a distinct _white

eye-ring_. Its back and wings are green, the throat yellow, and under

parts gray; the bill is thin and straight. Only other common small green

bird is the amakihi, which has no white around the eyes. Immatures are

duller, and the eye-ring, although present, is less distinct.

PARK DISTRIBUTION: Introduced from Japan in 1929. Now widely established

on all islands. Kilauea—Common almost everywhere in the park.

Haleakala—Fairly common throughout the park, except at the highest

elevations or in the barren portions of the crater.

VOICE: A thin, high-pitched song a bit like that of the house finch, but

much higher and not as loud. Note: a high _tsee_ or _chee_ given

repeatedly.

You will hear a rapid chittering of high notes as a flock of three or

four white-eyes fly into the nearby shrubbery. Notice how quickly they

work over the foliage and limbs gleaning tiny insects. They continue to

utter their notes as they feed, but soon one by one they are off again

to new vegetation.

The pattern of population increase for the white-eye has paralleled that

of many exotic species. Following their introduction in 1929 the birds

were at first slow to increase their range, but in more recent years a

population explosion has taken place ... on the Island of Hawaii, at

least. It is presently the commonest bird on the island and it seems to

have adapted to nearly every habitat. There is every indication that the

white-eye, competing for insects with native Hawaiian birds such as the

Hawaiian creeper, has virtually eliminated some of the natives from

their former habitat.

AMAKIHI _Loxops virens_

[Illustration: AMAKIHI

(male)]

DESCRIPTION: 4½″. Yellow-green with no outstanding markings, and a dark

slightly downcurved bill. The male is bright green above with a

yellowish breast, while the female and immatures are duller, tending

toward gray-green. It is a real problem to distinguish between a female

or young amakihi and the very rare Hawaiian creeper (next bird).

PARK DISTRIBUTION: Kilauea—Very common on the slopes of Mauna Loa around

tree-line (for example along the Mauna Loa trail); less common in the

wet ohia forests around Kilauea Crater and along the Chain of Craters

road. Haleakala—Common in the open forests such as Hosmer Grove and

Paliku.

VOICE: The usual song, a slow tinkling trill,

_tink-tink-tink-tink-tink-tink-tink_ or _wheedle-wheedle-wheedle_, etc.,

is uttered by the male. Commonest foraging note (both sexes) is a high

_djeee_; another note is _wheee_ with a rising inflection.

You will see a little green bird flit into a mamani or other nearby tree

and begin to seek insects among the foliage, visiting the blossoms for

nectar if the tree happens to be in bloom. You hear a buzzy _djeee_ and

you have made acquaintance with the amakihi. This Hawaiian honeycreeper

prefers more open forest than do the other two common members of the

family, the apapane and iiwi. But often all three are found together,

with the amakihis working through the entire foliage and not just in the

tree tops.

Seasonal movements are much less obvious than for either apapanes or

iiwis, probably because amakihis are less dependent on flowering

periods. However, some migration does occur, especially in and out of

their lower range below 3,000 feet elevation. Nesting is in late spring

and early summer.

HAWAIIAN CREEPER _Loxops maculata_

DESCRIPTION: 4½″. Very similar to the female or immature amakihi, but

the bill is straighter and tends to be lighter in color. Creepers search

for insects on the trunks and heavier branches, while amakihis usually

work more in the foliage.

PARK DISTRIBUTION: Kilauea—Now very rare in the upper rain forest or koa

parkland on Mauna Loa. Haleakala—Has not been definitely recorded within

the park for many years.

Twenty years ago creepers were often seen in the Mauna Loa Strip area of

the Kilauea Section, but from 1958-1960 the author saw only one. On the

other hand, introduced white-eyes have greatly increased their numbers

in recent years, and now they are by far the commonest bird along the

Mauna Loa Strip. White-eyes feed in much the same manner as

creepers—they carefully glean tiny insects from limbs of ohia, mamani,

and other trees. It seems likely that direct competition for insects by

the white-eyes is an important factor in the recent decline of Hawaiian

creepers.

OU _Psittirostra psittacea_

[Illustration: OU

(male)]

DESCRIPTION: 6½″. A greenish bird with a heavy _parrotlike bill_. Male:

Varying shades of green above, lighter below, with a _bright yellow

head_ that give it the appearance of being unusually large headed.

_Female and Immature_: Lack the yellow head.

PARK DISTRIBUTION: Kilauea—Rare; in the wet tree-fern jungle. Thurston

Lava Tube is within its range. Haleakala—Absent from Maui.

VOICE: A beautiful singer, according to Munro. Note: a medium

high-pitched _teweé_.

Ous are fairly inactive birds, often spending long periods quietly on

the branch of an ohia or other tree, and would be difficult to locate in

the dense forest except for the bright male plumage. They frequently

travel in pairs and apparently have a small individual range, for the

same pair may be seen day after day in one locality. Their food consists

of fruit.

APAPANE _Himatione sanguinea_

[Illustration: APAPANE

(immature and adult)]

DESCRIPTION: 5½″. Crimson red with black wings and tail, _white

abdomen_, and slightly down-curved _black bill_. Only similar species,

the iiwi, has a red abdomen and a long orange bill. Immatures are

confusing, as the red is mostly lacking. However, grayish birds having a

touch of rusty red on the sides and white under the tail, and feeding in

ohia tops, are surely this species. The throat and face of young

apapanes may appear yellow-orange.

PARK DISTRIBUTION: Kilauea—Common to abundant throughout the wet ohia

forest; much less common in the drier forests. Haleakala—Common locally

in forested areas such as Hosmer Grove or Paliku.

VOICE: You will hear a constant chorus of short songs and notes from the

highest ohia tops whenever apapanes are about. The quality varies from

sweet whistled notes to harsh chips and buzzes, usually intermixed.

Probably the most varied songster in the park.

The apapane is likely to be your first introduction to the endemic

Hawaiian honeycreepers. While most of Hawaii’s native birds have either

become extinct or are greatly reduced in numbers, this species seems to

have held its own wherever there are ohia trees to provide a supply of

lehua nectar. Examine a cluster of red ohia blossoms. You will find that

each tiny cup which bears long bright stamens is filled with honey. A

single ohia in full bloom with countless thousands of these nectar-cups

must produce many pounds of honey. No wonder one blossoming tree will

attract so many honeycreepers.

You will see the birds high in the trees, flitting about from flower to

flower, often stopping to pick up insects along the way. Although a few

trees are in bloom throughout the year in any given area, there are

definite “flowering periods” for the ohia when more than half of the

trees may be in full blossom. The season for these flowering periods

will vary among localities, and tremendous flocks of apapanes and other

honeycreepers follow the bloom from one area to another. They can often

be seen flying high overhead in small groups, all going in the same

direction. But even during times when the ohias are out of bloom a few

apapanes will remain in the forest.

The breeding season is an extended one, and you may see immature

apapanes with almost no sign of red plumage from February to October.

[Illustration: _Ohia blossom nectar is the staple food for the

apapane and iiwi_]

IIWI _Vestiaria coccinea_

[Illustration: IIWI]

DESCRIPTION: 5¾″. A brilliant scarlet body and _long, orange,

sickle-shaped bill_ distinguishes this honeycreeper. Lacks the white

abdomen of the apapane. Immatures appear greenish-yellow with patches of

red developing with age, but the long orange bill is always diagnostic.

PARK DISTRIBUTION: Kilauea—Common in the wet ohia forest, especially

when the trees are in bloom. Kipuka Puaulu and the vicinity of Thurston

Lava Tube are likely places. Haleakala—Fairly common in Hosmer Grove and

the forest behind Paliku.

VOICE: The creaking of a rusty gate, _ker-eeék_ is the best description

for its commonest note. Other calls include a sharp whistle and a short

warble, all rather harsh.

Look for this bright Hawaiian honeycreeper among flocks of apapanes in

the forest. On a calm day you will hear the heavy flutter of their wings

as they fly from tree to tree. Apapanes also have a similar feather

structure which produces such noisy flight.

Iiwis tend to feed more in the upper-middle branches rather than the

high tops, and they seem to remain in a single tree for a longer time

than the apapanes. Their food is made up of nectar (ohia, mamane, and

other flowers) which they suck up through tubular tongues that extend

the length of their sickle bills, and the larger insects. Old koa trees

often attract iiwis, presumably because of the insects.

You will see birds in green juvenile plumage any time from February

until autumn. These young birds seem to be especially affected by bird

lice, for they spend much time scratching and preening.

RICEBIRD _Munia nisoria_

[Illustration: RICEBIRD]

DESCRIPTION: 4″. A tiny, _dark-faced_ bird with a heavy blackish bill.

Differs from house sparrow and house finch females in its smaller size,

the dark face and throat, and under parts that look speckled. The flanks

may appear barred. Nearly always in flocks.

PARK DISTRIBUTION: Introduced to the islands about 1865. Now established

on all main islands. Kilauea—Occasional to common along most park roads

except in the Kau Desert and the upper Mauna Loa Strip. Haleakala—Absent

from the park.

VOICE: A short _wheek_ or _whireép_, softer than the chip of the house

finch, and usually repeated.

Ricebirds used to be great pests among the rice fields of lower

elevations, but their numbers have diminished now that little rice is

grown on the islands. Notice the flocks of half-a-dozen or so that fly

out with short wing beats along park roads, trails, or other places

where weeds thrive. They are primarily ground feeders and even in flight

they seldom rise much above the ground surface.

HOUSE SPARROW _Passer domesticus_

(also English sparrow)

DESCRIPTION: 6″. Almost everyone knows this chunky, grayish-brown bird

with a heavy bill, restricted to areas of human habitation. Males have

black throats; females gray.

PARK DISTRIBUTION: Introduced before 1870. Kilauea—Restricted to areas

of human habitations. Haleakala—A few around Park Headquarters, mainly

during the summer months.

VOICE: Dull chirps.

CARDINAL _Richmondena cardinalis_

[Illustration: CARDINAL

(female and male)]

DESCRIPTION: 4″-10″. _Male_—the only _all red bird with a crest_.

_Female_—yellowish-brown with some red, also crested. Both sexes have a

heavy red bill: however, immatures, which resembles females, have dark

beaks.

PARK DISTRIBUTION: Introduced on several islands since 1929.

Kilauea—Fairly common locally in the drier vegetated areas such as

Kipuka Puaulu. Haleakala—Absent from the park.

VOICE: The song, which may be varied, is made up of a liquid whistled

phrase usually repeated. Note: a sharp _tik_.

Visitors from the eastern states will recognize familiar birdcalls when

a cardinal is nearby. They are usually rather shy birds here, so you

will probably hear them first. Seeds, insects, and fruit make up the

diet of these birds. They are often found in company with the red-billed

leiothrix.

HOUSE FINCH _Carpodacus mexicanus_

(also linnet or papaya bird)

[Illustration: HOUSE FINCH

(female and male)]

DESCRIPTION: 5½″. _Male_—Grayish-brown with rosy red breast, forehead,

stripe over eye, and rump. At Haleakala the color is more yellow than

red. _Female_ and _Immature_—Sparrowlike with a gray-brown back and

dusky-white streaked breast. House finches have thick seed-eating bills.

PARK DISTRIBUTION: Introduced before 1870. Kilauea—very common in the

drier sections of the park, especially along the Hilina Pali road and at

Kipuka Puaulu. Haleakala—One of the commonest birds in the park both

inside and out of the crater.

VOICE: A rapid, disjointed warbling song, usually lasting several

seconds. Note: one or a series of chirps, more musical than that of the

house sparrow.

This is strictly a social species living in flocks ranging in size from

a few birds to 20 or more. On the Island of Hawaii the introduced house

finch has adapted well to a habitat that is presently unoccupied by any

native resident—the dry grassy regions of the Kau Desert and along

Hilina Pali.

On the mainland house finches are reddish; the same is true for most

Kilauea birds. However, at Haleakala the usual color of the male is

yellow or orange. It seems likely that diet, which is known to affect

pigmentation in bird plumage, rather than heredity, is the cause of this

difference.

OTHER BIRDS

Accidentals

From time to time various sea and other birds passing over the island or

blown inland during a storm may be observed in either park. In recent

years such accidentals have included:

Red-footed booby (_Sula sula_): one record, Kilauea (1959).

Peregrine falcon (_Falco peregrinus_): seen at Kilauea during 1961.

Red phalarope (_Phalaropus fulicarius_): one record, Kilauea (1949).

Gray-backed tern (_Sterna lunata_): one record, Kilauea (1959).

Formerly Recorded

Several native birds that were formerly found within the park have not

been recorded in recent years. They include:

Hawaiian crow (_Corvus tropicus_): This, the only crow here and endemic

to the Island of Hawaii, formerly occurred within the park. One recent

Kilauea record (1940).

Akepa (_Loxops coccinea_): A tiny (4½″) bird. _Male_: Red-orange with no

white markings. _Female_: Green above and yellow below. Still occurs in

the koa forests northeast of the Mauna Loa Strip. Last park record was

over 20 years ago.

Akiapolaau (_Hemignathus wilsoni_): 5½″. Like the amakihi but with a

long, curved upper mandible overlapping the short straight lower bill.

Used to be a permanent resident of the koa kipukas along the Mauna Loa

Strip, but has not been observed within the park for several years.

Parrot-billed koa finch (_Pseudonestor xanthophrys_): 5½″. A yellowish

parrotlike bird with a heavy hooked beak that formerly occurred in Kaupo

Gap at Haleakala. Last record, a few miles outside the park, was in

1950.

Status Uncertain

Game birds are sometimes released by the State Division of Fish and Game

near the park, but they do not always become established. A recent

release (June 1960) just outside the park boundary near Headquarters at

Haleakala was the Erckel’s Francolin (_Francolinus erckelii_). This

large chickenlike partridge can be recognized by its rusty-red crown. It

is not yet known whether the birds will reproduce and become

established.

INDEX

A

Acknowledgements 9

_Acridotheres tristis_ 27

Akepa 34

Akekeke 20

Akiapolaau 34

_Alauda arvensis_ 22

_Alectoris graeca_ 16

Amakihi 3, 5, 7, 28, Plate

_Anoüs tenuirostris_ 20

Apapane 3, 5, 6, 7, 29, 30, 31, 32, Plate

_Arenaria interpres_ 20

_Asia flammeus_ 22

B

Bird Park 6

Booby, red-footed 34

_Branta sandvicensis_ 13

_Buteo solitarius_ 15

C

Cardinal 4, 6, 33, Plate

_Carpodacus mexicanus_ 33

Chain of Craters Road 18, 21, 28

_Chasiempsis sandwichensis_ 26

Chukar 7, 16

_Corvus tropicus_ 34

Crater Rim Drive 5, 18

Creeper, Hawaiian 29

Crow, Hawaiian 34

D

Dove

barred 21, 22

Chinese 21

laceneck 21

spotted 21

Drepaniidae 3

E

Elepaio 3, 6, 26, Plate

Endemics 3

Exotics 4

F

Fern jungle 2, 5, 6

Finch

house 6, 7, 33, Plate

parrot-billed koa 34

Francolin, Erckel’s 34

_Francolinus erckelii_ 34

G

_Geopelia striata_ 22

Goose, Hawaiian 13

H

Haleakala National Park 7, 8

Halemaumau 6, 12

Halape 20

Hawaiian Islands 3

Hawaiian Honeycreepers 3

Hawaii Volcanoes National Park 8

Hawk, Hawaiian 6, 15

_Hemignathus wilsoni_ 34

_Heteroscelus incanum_ 20

Hilina Pali 12, 21, 22, 27, 33

Hill robin, Japanese 24

_Himatione sanguinea_ 30

Holua Cabin 11, 12

Hosmer Grove 7, 28, 30

Hui Manu 4

I

Iiwi 3, 5, 6, 7, 29, 31, Plate

Io 3, 6, 15

K

Kalapana—Kalapana Road 21, 22

Kapalaoa Cabin 11

Kau Desert 12, 27, 32, 33

Kaupo Gap 34

Kilauea Crater 11, 16, 17, 19, 20, 23, 26, 28

Kilauea Iki 6, 15

Kilauea Volcano 5

Kipuka Nene 16

Kipuka Puaulu 1, 6, 26, 33

Koae 11

Kolea 19

Kona Coast 22

L

_Leiothrix lutea_ 24

Leiothrix, red-billed 6, 24, 33, Plate

Linnet 33

_Lophortyx californicus_ 15

_Loxops_

_coccinea_ 34

_maculata_ 29

_virens_ 28

M

Malaria, avian 5, 24

Makaopuhi Crater 15

Mauna Kea 11

Mauna Loa—Mauna Loa Strip 6, 11, 13, 14, 15, 16, 18, 19, 22, 23, 28,

29, 32

Mejiro 27

_Mimus polyglottus_ 24

Mockingbird 7, 24

_Munia nisoria_ 32

Mynah 4, 27, Plate

N

Nene 3, 7, 13, back cover

Nightingale, Peking 24

Noddy, white-capped 20

Noio 20

O

Old World flycatcher 3, 27

Owl, Hawaiian short-eared 3, 22

Omao 3, 25, 27, Plate

Ou 29, Plate

P

Paliku 7, 12, 22, 24, 28, 30

Papaya bird 33

_Passer domesticus_ 32

Petrel, dark-rumped 4, 10, 11

_Phaeornis obscura_ 25

_Phaëthon lepturus_ 11

Phalarope, red 34

_Phalaropus fulicarius_ 34

_Phasianus colchicus torquatus_ 17

_colchicus versicolor_ 18

Pheasant

Chinese 17

green 18

Japanese blue 6, 7, 18

ring-necked 7, 17

versicolor 18

Plover, American golden 4, 7, 19

_Pluvialis dominica_ 19

_Pseudonestor xanthophrys_ 34

_Psittirostra psittacea_ 29

Pueo 22

_Pterodroma phaeopygia_ 11

Q

Quail, California 4, 7, 15

R

Ricebird 32, Plate

_Richmondena cardinalis_ 33

S

Skylark 7, 22, Plate

Sparrow

English 32

house 32

_Streptopelia chinensis_ 21

_Sterna lunata_ 34

_Sula sula_ 34

T

Tattler, wandering 20

Tern, gray-backed 34

Thrush

Chinese 23

Hawaiian 25

spectacled 23

Thurston Lava Tube 2, 5, 25, 29

_Trochalopterum canorum_ 23

Tropic-bird, white-tailed 4, 6, 11, 12

Turnstone, ruddy 20

U

Uau 11

Ulili 20

V

_Vestiaria coccinea_ 31

W

White-eye 4, 5, 6, 27, 29, Plate

Z

_Zosterops palpibrosus_ 27

Boldfaced type: refers to illustrations

OTHER PARK NATURE BOOKLETS

The Hawaii Natural History Association, a nonprofit organization devoted

to aiding the park interpretive program, has produced several other

booklets to help you enjoy the parks in Hawaii. These may be obtained at

headquarters in either park or by writing directly to the association,

Hawaii Volcanoes National Park, Hawaii.

_Haleakala Guide_, by George C. Ruhle, $1.00

_Ferns of Hawaii National Park_, by Douglass H. Hubbard, 50¢

_Trailside Plants of Hawaii National Park_, by Douglass H. Hubbard and

Vernon R. Bender, Jr., 50¢

_Volcanoes of the National Parks in Hawaii_, by Gordon A. MacDonald

and Douglass H. Hubbard, 50¢

_NOTES_

[Illustration: PHOTO BY THE AUTHOR

_Nene_]

Transcriber’s Notes

—Silently corrected a few typos.

—Retained publication information from the printed edition: this eBook

is public-domain in the country of publication.

—Included images from the color plate beside the corresponding species

descriptions.

—In the text versions only, text in italics is delimited by

_underscores_.

End of the Project Gutenberg EBook of Birds of the National Parks in Hawaii, by

William W Dunmire (1930-)

*** END OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK BIRDS OF THE NATIONAL PARKS ***

***** This file should be named 59398-0.txt or 59398-0.zip *****

This and all associated files of various formats will be found in:

http://www.gutenberg.org/5/9/3/9/59398/

Produced by Stephen Hutcheson and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Updated editions will replace the previous one--the old editions will

be renamed.

Creating the works from print editions not protected by U.S. copyright

law means that no one owns a United States copyright in these works,

so the Foundation (and you!) can copy and distribute it in the United

States without permission and without paying copyright

royalties. Special rules, set forth in the General Terms of Use part

of this license, apply to copying and distributing Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works to protect the PROJECT GUTENBERG-tm

concept and trademark. Project Gutenberg is a registered trademark,

and may not be used if you charge for the eBooks, unless you receive

specific permission. If you do not charge anything for copies of this

eBook, complying with the rules is very easy. You may use this eBook

for nearly any purpose such as creation of derivative works, reports,

performances and research. They may be modified and printed and given

away--you may do practically ANYTHING in the United States with eBooks

not protected by U.S. copyright law. Redistribution is subject to the

trademark license, especially commercial redistribution.

START: FULL LICENSE

THE FULL PROJECT GUTENBERG LICENSE

PLEASE READ THIS BEFORE YOU DISTRIBUTE OR USE THIS WORK

To protect the Project Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting the free

distribution of electronic works, by using or distributing this work

(or any other work associated in any way with the phrase "Project

Gutenberg"), you agree to comply with all the terms of the Full

Project Gutenberg-tm License available with this file or online at

www.gutenberg.org/license.

Section 1. General Terms of Use and Redistributing Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works

1.A. By reading or using any part of this Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic work, you indicate that you have read, understand, agree to

and accept all the terms of this license and intellectual property

(trademark/copyright) agreement. If you do not agree to abide by all

the terms of this agreement, you must cease using and return or

destroy all copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in your

possession. If you paid a fee for obtaining a copy of or access to a

Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work and you do not agree to be bound

by the terms of this agreement, you may obtain a refund from the

person or entity to whom you paid the fee as set forth in paragraph

1.E.8.

1.B. "Project Gutenberg" is a registered trademark. It may only be

used on or associated in any way with an electronic work by people who

agree to be bound by the terms of this agreement. There are a few

things that you can do with most Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works

even without complying with the full terms of this agreement. See

paragraph 1.C below. There are a lot of things you can do with Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works if you follow the terms of this

agreement and help preserve free future access to Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic works. See paragraph 1.E below.

1.C. The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation ("the

Foundation" or PGLAF), owns a compilation copyright in the collection

of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works. Nearly all the individual

works in the collection are in the public domain in the United

States. If an individual work is unprotected by copyright law in the

United States and you are located in the United States, we do not

claim a right to prevent you from copying, distributing, performing,

displaying or creating derivative works based on the work as long as

all references to Project Gutenberg are removed. Of course, we hope

that you will support the Project Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting

free access to electronic works by freely sharing Project Gutenberg-tm

works in compliance with the terms of this agreement for keeping the

Project Gutenberg-tm name associated with the work. You can easily

comply with the terms of this agreement by keeping this work in the

same format with its attached full Project Gutenberg-tm License when

you share it without charge with others.

1.D. The copyright laws of the place where you are located also govern

what you can do with this work. Copyright laws in most countries are

in a constant state of change. If you are outside the United States,

check the laws of your country in addition to the terms of this

agreement before downloading, copying, displaying, performing,

distributing or creating derivative works based on this work or any

other Project Gutenberg-tm work. The Foundation makes no

representations concerning the copyright status of any work in any

country outside the United States.

1.E. Unless you have removed all references to Project Gutenberg:

1.E.1. The following sentence, with active links to, or other

immediate access to, the full Project Gutenberg-tm License must appear

prominently whenever any copy of a Project Gutenberg-tm work (any work

on which the phrase "Project Gutenberg" appears, or with which the

phrase "Project Gutenberg" is associated) is accessed, displayed,

performed, viewed, copied or distributed:

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and

most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no

restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it

under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this

eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the

United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you

are located before using this ebook.

1.E.2. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is

derived from texts not protected by U.S. copyright law (does not

contain a notice indicating that it is posted with permission of the

copyright holder), the work can be copied and distributed to anyone in

the United States without paying any fees or charges. If you are

redistributing or providing access to a work with the phrase "Project

Gutenberg" associated with or appearing on the work, you must comply

either with the requirements of paragraphs 1.E.1 through 1.E.7 or

obtain permission for the use of the work and the Project Gutenberg-tm

trademark as set forth in paragraphs 1.E.8 or 1.E.9.

1.E.3. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is posted

with the permission of the copyright holder, your use and distribution

must comply with both paragraphs 1.E.1 through 1.E.7 and any

additional terms imposed by the copyright holder. Additional terms

will be linked to the Project Gutenberg-tm License for all works

posted with the permission of the copyright holder found at the

beginning of this work.

1.E.4. Do not unlink or detach or remove the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License terms from this work, or any files containing a part of this

work or any other work associated with Project Gutenberg-tm.

1.E.5. Do not copy, display, perform, distribute or redistribute this

electronic work, or any part of this electronic work, without

prominently displaying the sentence set forth in paragraph 1.E.1 with

active links or immediate access to the full terms of the Project

Gutenberg-tm License.

1.E.6. You may convert to and distribute this work in any binary,

compressed, marked up, nonproprietary or proprietary form, including

any word processing or hypertext form. However, if you provide access

to or distribute copies of a Project Gutenberg-tm work in a format

other than "Plain Vanilla ASCII" or other format used in the official

version posted on the official Project Gutenberg-tm web site

(www.gutenberg.org), you must, at no additional cost, fee or expense

to the user, provide a copy, a means of exporting a copy, or a means

of obtaining a copy upon request, of the work in its original "Plain

Vanilla ASCII" or other form. Any alternate format must include the

full Project Gutenberg-tm License as specified in paragraph 1.E.1.

1.E.7. Do not charge a fee for access to, viewing, displaying,

performing, copying or distributing any Project Gutenberg-tm works

unless you comply with paragraph 1.E.8 or 1.E.9.

1.E.8. You may charge a reasonable fee for copies of or providing