*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK 75020 ***

Transcriber’s notes:

The text of this e-book has been preserved as in the original,

including archaic spellings, but some illustrations have been

repositioned closer to the relevant text. Italic text is denoted by

_underscores_. Subscripted text is enclosed within curly brackets

preceded by an underscore.

[Illustration: AN OPERATION ON THE EYE

From an MS. of the XIII century]

[Illustration: A SURGEON PERFORMING AN OPERATION

From a woodcut of the XVII century]

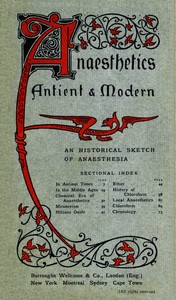

ANÆSTHETICS

ANTIENT AND MODERN

AN

HISTORICAL SKETCH

OF

ANÆSTHESIA

BURROUGHS WELLCOME & CO.

London (Eng.)

_Branches_: New York Montreal Sydney Cape Town

[All rights reserved

INDEX

PAGE

Anæsthesia, Dawn of, 7

Anæsthesia, Chloroform for, 69

Anæsthesia in Romance, 23

Anæsthesia in Roman Times, 17

Anæsthesia in the Antient Poets, 25

Anæsthesia, Local, in Antient Times, 27

Anæsthetic, an Antient Chinese, 18

Anæsthetics, Early Egyptian, 7

Anæsthetic, an Early Irish, 19

Anæsthetic, Freezing as an, 27

Anæsthetic, Mesmerism as an, 34

Anæsthetics used by the Hindus, 18

Anæsthetics, Chemical Era of, 30

Anæsthetics in the Middle Ages, 19

Anæsthetics, Local, 67

Anæsthetics of Antient Greece, 11

Carbon Tetrachloride, 67

Chloric Ether, 58

Chloroform, Discovery of, 58

Chronology, 73

Cocaine, 68

Colton, Dr. G. Q., 41

Davy, Sir Humphry, 33

Ether Epoch, 44

Ether, Sulphuric, 33

Ethyl Bromide, 67

Eucaine, 68

Faraday, Michael, 33

Holmes, Dr. Oliver Wendell, 52

Hypnotism, 37

Indian Hemp, 9

Jackson, Charles T., 50

“Letheon”, 52

Lycoperdon, 19

Mandragora, 11

Methyl Chloride, 66

Morphine, 29

Morton, W. T. G., 54

Nitrous Oxide Era, 41

Novocaine, 69

Opium, 27

Oxygen, 30

Priestley, Joseph, 32

Simpson, Sir James Young, 63

Stovaine, 69

Sulphuric Ether, 33

Wells, Horace, 42

[Illustration:

Comment adam et eue furent crees au ij · et au · iiij · c · de genesis

_From a woodcut of the XV century_

“And the Lord God caused a deep sleep to fall upon Adam, and he

slept: and He took one of his ribs, and closed up the flesh instead

thereof.”

_Genesis, chap. ii, verse 21_]

ANÆSTHETICS, ANTIENT AND MODERN

AN HISTORICAL SKETCH OF ANÆSTHESIA

“So God empal’d our Grandsire’s (Adam’s) lively look,

Through all his bones a deadly chilness strook,

Siel’d up his sparkling eyes with Iron bands,

Led down his feet (almost) to Lethe’s sands;

In briefe so numm’d his Soule’s and Bodie’s sense,

That (without pain) opening his side from thence

He took a rib, which rarely He refin’d,

And thereof made the mother of Mankind.”

[Sidenote: The Dawn of Anæsthesia]

Thus a sixteenth century poet quaintly describes, and draws an

impression of, from sacred records, the first operation tempered

by anæsthesia. It has been claimed that in the “deep sleep” that

the Creator “caused to fall upon Adam” is the germ of the idea of

anæsthesia that has come down to us from the dim ages of the past. It

is probable that primitive man employed digital compression of the

carotid arteries to produce anæsthesia, as the aboriginal inhabitants

of some countries do to-day. According to Caspar Hoffmann, this method

was practised by the antient Assyrians before performing the operation

of circumcision. Curiously enough the literal translation of the Greek

and Russian terms for the carotid is “the artery of sleep.”

[Sidenote: Early Egyptian anæsthetics]

The antient Egyptians are believed to have used Indian hemp and the

juice of the poppy to cause a patient to become drowsy before a

surgical operation. Pliny relates that they applied to painful wounds

a species of rock brought from Memphis, powdered, and moistened with

sour wine, which is the first record we have of local anæsthesia with

carbonic acid gas.

[Sidenote: The “Wine of the Condemned”]

The “sorrow-easing drug” which, as we are told in the fourth book of

the “Odyssey,” was given by Helen to Ulysses and his comrades, probably

consisted of poppy juice and Indian hemp. It is indeed actually

stated that she learned the composition from Polydamnia, the wife of

Thone, in Egypt. It is possible also that the “wine of the condemned,”

mentioned by the prophet Amos, may have been a preparation of these

drugs.

[Illustration: MANDRAGORA (_the Phallus of the Field_)

Inscribed in cuneiform characters and in Egyptian hieroglyphics ca.

3000 B.C.]

There are several passages in the Talmud which point to the fact that

the practice of easing the pain of torture and death, by stupefying the

sufferers, was a very antient one.

Thus it is stated: “If a man is led forth to death, he is given a cup

of spiced wine to drink, whereby his soul is wrapped in night”; and

again, “Give a stupefying drink to him that loseth his life, and wine

to those that carry bitterness in their heart.”

In connection with crucifixion, which was a common punishment for

malefactors among the Jews before the Christian era, with the sanction

of the Sanhedrin, the women were wont to ease the terrible death agony

of the sufferers by giving them something in the nature of a “wine of

the condemned” upon a sponge. It is probable that the “wine mingled

with myrrh” which, according to St. Mark, was offered to Christ before

nailing Him upon the Cross, was indeed a narcotic draught, given with

the object of lessening His sensibility to the agony.

The earliest reference to anæsthesia by inhalation is contained in the

works of Herodotus, who states that the Scythians were accustomed to

produce intoxication by inhaling the vapour of a certain kind of hemp,

which they threw upon the fire or upon stones heated for the purpose.

This was probably _Cannabis indica_, or Indian hemp, which was

employed by Oriental races as an anæsthetic from very early times.

[Sidenote: Anodyne poultices to deaden pain]

At the siege of Troy the Greek army surgeons employed anodyne and

astringent poultices to assuage the pain of the wounded. Thus

Patroclus, when his dagger from the thigh of Euryphylus--

Cut out the biting shaft; and from the wound

With tepid water cleansed the clotted blood;

Then, pounded in his hands, the root applied

Astringent, anodyne, which all his pain

Allay’d; the wound was dried, and stanched the blood.

_Iliad._

[Illustration: GATHERING MANDRAGORA

From an MS. of the XII century]

From this interesting description of the manner in which the early

Greek surgeons treated a wound, it is evident that, although they had

no actual knowledge of anæsthetics, they had found from experience the

advantage of cleansing the wound and applying an astringent and anodyne

dressing to deaden sensibility to pain, which probably, unknown to

them, also possessed antiseptic qualities.

MANDRAGORA AS AN ANÆSTHETIC

[Sidenote: The anæsthetics of antient Greece]

That the early Greeks also used certain methods for deadening

sensibility to pain is evidenced by several of the antient writers.

Pindar states “Machaon eased the sufferings of Philoctetes with a

narcotic potion.” Theocritus also alludes to Lucina, the goddess of the

obstetric art, as “pouring an insensibility to pain down all the limbs

of a woman in the throes of labour.” Aphrodite, to assuage her grief

for the death of Adonis, is said to have thrown herself on a bed of

lettuce and mandragora.

There is no medicinal plant around which cluster more mysterious and

quaint associations than mandragora. The Babylonians employed it more

than 2000 years B.C., and a figure cut from the root was used at that

early period as a charm against sterility. It is probable that the

antient Hebrews also believed it to possess these properties, judging

from the story of Rachel related in the book of Genesis. The early

Egyptians employed mandragora, which they called the “phallus of the

field,” as a medicinal agent, both as an anodyne and an anæsthetic, and

also used it in many of their superstitious rites.

[Illustration: GATHERING MANDRAGORA

From an MS. of the XIII century

“To gather ye mandragora, go forthe at dead of nyght and take a dogge

or other animal and tye hym wyth a corde unto ye plante. Loose ye

earth round about ye roote, then leave hym, for in hys struggles to

free hymself he wyll teare up ye roote, which by its dreadfull cryes

wyll kyll ye animal.”]

Theophrastus is the earliest writer on botany to allude to the virtues

of mandragora, among which he mentions its property of inducing

sleep, and of its use as an aphrodisiac in love potions. The Greeks

gave mandragora the name of “Circeum,” derived from that of the witch

Circe, and believed that an evil spirit dwelt in the plant; for, when

uprooted, it was said to utter such frightful shrieks that no mortal

man might hear them and live.

To prevent this catastrophe, it was usual in gathering the plant

to take a dog and let him be sacrificed to the rage of the demon.

This method is thus described by an antient writer:--“To gather ye

mandragora, go forthe at dead of nyght and take a dogge or other animal

and tye hym wyth a corde unto ye plante. Loose ye earth round about ye

roote, then leave hym, for in hys struggles to free hymself he will

teare up ye roote, whych by its dreadfull cryes wyll kyll ye animal.”

Certain rites and ceremonies were sometimes performed before gathering

the root, such as making three circles round it with a sword, and the

earth being loosened with an ivory spade, while to drown the cries of

the fatal herb a horn was sometimes blown by the gatherer.

According to an antient German legend, the mandragora always grew with

greater luxuriance beneath or near a gallows, for the flesh of the

felons hanged thereon was believed to nourish the mysterious root in

which the demon dwelt. Another legend current was, that the leaves of

the plant sometimes glowed with a peculiar light at night.

The supposed likeness of the root to the human form gave rise to many

of the superstitions connected with mandragora, and it was believed in

early times that there were actually two distinct species, viz., male

and female. These roots were often carved to resemble the human figure,

and were worn as charms to ward off disease.

[Illustration: MANDRAGORA

From an MS. of the XV century]

[Sidenote: Mandragora as an anæsthetic]

The first mention of mandragora (_Mandragora Atropa, L._), as an

anæsthetic, is made by Dioscorides (_ca._ A.D. 100), who evidently

recognised the difference between the hypnotic and anæsthetic effects

of the drug, from which one may assume that it was employed for both

purposes in the medical practice of that day. Respecting the former,

he states: “Eating which [mandragora] shepherds are made sleepy,” and,

referring to the latter property, he remarks that “three wine-glassfuls

of a liquid preparation of the root are given to those who are about to

be cut or burnt, for they do not feel the pain.”

Of the preparations of mandragora, he gives the following: “There are

those who boil the root in wine to a third part, and preserve the

decoction, of which they give a cyathus [small glass] in want of sleep

or severe pains in any part, and also before operations with the knife,

or the actual cautery, that they may not be felt”; also “a wine is

prepared from the bark of the root, without boiling, and three pounds

of it are put in a cadus [eighteen gallons] of sweet wine; of this,

three cyathi are given to those who require to be cut or cauterised,

when, being thrown into a deep sleep, they do not feel any pain.”

[Sidenote: “Morion,” a Grecian anæsthetic]

Dioscorides also refers to a substance called “morion,” believed to be

the white seed of the mandragora root, which is mentioned also by Pliny

as a narcotic poison. “A drachm of it,” he states, “taken in a draught,

or in a cake or other food, causes infatuation, and takes away the use

of the reason; the person sleeps without sense, in the attitude in

which he ate it, for three or four hours afterwards. Physicians use it

when they have to resort to cutting or burning.”

These allusions serve to prove how frequently anæsthesia was practised

by the physicians of antient Greece, to whom the narcotic property of

mandragora, which is allied to _Atropa Belladonna_, or deadly

nightshade, was well known.

[Illustration: GATHERING MANDRAGORA

From a drawing of the XVI century

The plant is being uprooted by the struggling dog, whilst a horn is

blown to drown the cries of the fatal herb]

The younger Pliny (A.D. 32–79), in his “Natural History,” also

describes the use of mandragora as a narcotic, and gives preference to

the use of the leaves over the root for that purpose. “The dose,” he

says, “is half a cyathus, taken against serpents, and before cuttings

and puncturings, that they may not be felt.” He further adds: “For

these purposes it is sufficient for some persons to seek sleep from the

smell,” from which it is clear that this anæsthetic was also used by

inhalation.

With reference to mandragora, Sir Benjamin Ward Richardson once

prepared a draught according to one of the recipes given by

Dioscorides, and took it. He tells us that “the phenomena repeated

themselves with all faithfulness, and there can be no doubt that, in

the absence of our now more convenient anæsthetics, ‘morion’ might

still be used with some measure of efficacy for general anæsthesia.”

Further allusion is made to mandragora as a surgical anæsthetic by

Apuleius in his “Liber de Herbis,” in which he says: “If anyone is to

have a limb mutilated, burnt, or sawn, he may drink half an ounce of

mandragora with wine; and while he sleeps the member may be cut off

without any pain or sense.”

Avicenna, the Father of Arabian medicine, gives special directions as

to the employment of mandragora, both as an anæsthetic and a hypnotic;

while Averrhöes, another Arabian physician, refers to the soporific

effects of the fruit of the same plant. Galen also alludes to its

powers to paralyse sensation, and Paulus Ægineta states: “Its apples

are narcotic, when smelled to, and also their juice, that if persisted

in they will deprive the person of his speech.” According to Isidorus,

“a wine of the bark is given to those about to undergo operations,

that, being asleep, they feel no pain”; and Serapion confirms this

statement in his works.

[Sidenote: Anæsthesia in Roman times]

Evidence of the practice of surgical anæsthesia is to be found in the

writings of several physicians during the time of the Roman Empire.

It is probable that the practice came to them from the Greek school,

for mandragora, which they almost invariably used, grew largely in the

Grecian Archipelago. Celsus recommends a pillow of mandragora apples to

induce sleep.

HINDU ANÆSTHETICS

From ancient records it appears probable, that the Hindus inhaled the

fumes of burning Indian hemp as an anæsthetic at a period of great

antiquity. As early as the year 977 they also knew of other drugs which

they employed for the same purpose.

Pandit Ballala describes an interesting surgical operation which was

performed on King Bhoja at that period. The patient was suffering from

severe pain in the head, and, his condition becoming critical, two

brother-physicians happened to arrive in Dhar, who, after carefully

considering the case, came to the conclusion that a surgical operation

was necessary to give relief. They are said to have administered to him

a drug called _sammohini_ to render him insensible, and while he

was completely under its influence they trepanned his skull and removed

the real cause of the complaint. They closed the opening, stitched up

the wound, and applied a healing balm.

After the operation, they are said to have administered to the King a

drug called _sanjivini_, to accelerate the return of consciousness

and to minimise the chances of death.

[Sidenote: An antient Chinese anæsthetic]

It is recorded that “a Chinese physician named Hoa-Tho, who lived about

A.D. 220 or 230, was accustomed to administer to his patients on whom

he wished to perform painful operations, a preparation called ‘Ma-yo’

(Indian hemp, probably), the effect of which was that, after a few

moments, they became insensible as if they were deprived of life.”

Miss Isabella Bird, when visiting the Tung-wah Hospital, in Hong-Kong,

states: “The native surgeons do not use chloroform in operations, but

they possess drugs which throw their patients into a profound sleep,

during which the most severe operations can be performed. One of them

showed me a bottle containing a dark brown powder, which, he said,

produced this result; but he would not divulge the name of one of its

constituents, saying it was a secret taught him by his tutor.”

From very early times the fumes of burning lycoperdon (_Lycoperdon

gygantum_) have been used for stupefying bees before taking honey

from the hive.

Thus it will be seen from the many allusions we have quoted from

writers in the early ages, it is evident that mandragora and Indian

hemp were the two drugs which were more or less in general use as

anæsthetics in antient times.

ANÆSTHETICS IN THE MIDDLE AGES

[Sidenote: An early Irish anæsthetic]

In a Celtic manuscript of the twelfth century on materia medica, a

preparation called “potu oblivionis” is mentioned, of which mandragora

was probably an ingredient. A draught of this preparation was used by

the early Irish to induce sleep.

[Sidenote: The “Sleeping Sponge”]

[Sidenote: Method of using the “Sleeping Sponge”]

Coming to the fifteenth century, the method of producing insensibility

to pain by the inhalation of the volatile principles of drugs, which

had been handed down by tradition from the early ages, seems to have

been revived by Hugo of Lucca, a Tuscan physician. He is described

as “chief of a school of surgeons that treated wounds with wine,

oakum and bandaging, with happy success.” Theodoric, his son, who

was a monk-physician, and practised surgery, mentions, in 1490, a

preparation used by his father which he calls “oleum de lateribus.”

This he describes as “a most powerful caustic, and a soporific which,

by means of smelling alone, could put patients to sleep on occasion of

painful operations which they were to suffer.” The mixture was placed

on a sponge in hot water, and then applied to the nostrils of the

patient, and was called the “spongia somnifera.” The following is the

composition of the “sleeping sponge” and the method of using, as stated

by Theodoric: “Take of opium, of the juice of the unripe mulberry, of

hyoscyamus, of the juice of hemlock, of the juice of the leaves of

mandragora, of the juice of the woody ivy, of the juice of the forest

mulberry, of the seeds of lettuce, of the seeds of dock, which has

large round apples, and of the water-hemlock, each an ounce: mix all

these in a brazen vessel, and then place in it a new sponge; let the

whole boil as long as the sun lasts on the dog-days, until the sponge

consumes it all, and has boiled away in it. . . . As oft as there shall

be need of it, place this sponge in hot water for an hour, and let it

be applied to the nostrils of him who is to be operated on until he has

fallen asleep, and so let the surgery be performed.”

[Illustration: AN OPERATION ON THE LIVER

From an MS. of the XIV century]

According to Bodin, the sleep produced was so profound that the patient

often continued in that condition for several days afterwards. The

method of arousing the patient employed by Hugo, however, is thus

described: “In order to awaken him, apply another sponge, dipped in

vinegar, frequently to the nose, or throw the juice of fenugreek into

the nostrils; shortly he awakens.”

According to Canappe, in his work “Le Gyidon pour les Barbiers et

les Chirurgiens,” published in 1538, the “Confectio soporis secundum

dominum Hugonem” was used by surgeons at that period.

[Illustration: A SURGEON AMPUTATING A LEG

From a woodcut of the XVI century]

Reginald Scott, in a work written in the sixteenth century, gives the

following recipe for making an anæsthetic: “Take of opium, mandragora

bark and henbane root, equal parts; pound them together, and mix with

water. When you want to sew or cut a man, dip a rag in this, and put it

to his forehead and nostrils. He will soon sleep so deeply that you

may do what you will. To wake him up, dip the rag in strong vinegar.

The same is excellent in brain-fever, when the patient cannot sleep;

for if he cannot sleep, he will die.”

[Sidenote: Anæsthesia in romance]

The writers and poets of mediæval romance in more than one instance

allude to anæsthesia produced by drugs. Boccaccio, who wrote his

“Decameron” in 1352, in the story of Dionius, alludes to a certain

anæsthetic liquid of Surgeon Mazzeo della Montagna, of Salerno. “The

doctor,” he says, “supposing that the patient would never be able to

endure the pain without a soporific, deferred the operation until the

evening, and in the meantime ordered the water to be distilled from a

certain composition, which, being drunk, would throw a person asleep as

long as he judged it necessary.” Boccaccio, probably, borrowed his idea

from the recipe given by Nichols, a provost of the famous old school of

Salerno, who published a recipe for making an anæsthetic, similar to

that of Reginald Scott.

In Brooke’s “Tragicall Historye of Romeus and Julietta,” printed in

1562, which supplied Shakespeare with the plot and much material for

his play “Romeo and Juliet,” Friar Laurence thus speaks to Julietta: “I

have learned and proved of long time the composition of a certain paste

which I make of divers somniferous simples, which beated afterwards

to powdere, and dronke with a quantitie of water, within a quarter of

an houre after, bringeth the receiver into such a sleepe, and burieth

so deeply the senses and other spirits of life that the cunningest

phistian will judge the party died.

“And, besides that, it hath a more marvellous effect, for the person

which useth the same feeleth no kind of grief, and, according to the

quantitie of the draught, the patient remaineth in a sweete sleepe; but

when the operation is perfect and done, he returneth unto his first

estate.”

[Illustration: A SURGEON AMPUTATING A LEG

From a woodcut of the XVI century]

Shakespeare’s references to mandragora, poppy and other “drowsy

syrups,” are too well known to need quotation; but the following

allusion by Middleton, in his play called “Women beware Women!” is not

without interest:--

I’ll imitate the pities of old surgeons

To this lost limb, who, ere they show their art,

Cast one asleep, then cut the diseased part.

William Bulleyn, the author of “A Bulwark of Defence against Sickness,”

who practised as a surgeon in the reign of Henry VIII, describes an

anæsthetic which he directs to be prepared from the juice of a certain

herb (probably mandragora) “pressed forth, and kept in a closed earthen

vessel according to art, bringeth deep sleep, and casteth man into a

trance, or deep terrible sleep, until he shall be cut of the stone.”

[Sidenote: Allusions to anæsthesia by antient poets]

The poet Marlowe thus refers to mandragora in his play “The Jew of

Malta”:--

_Barabas_:

I drank of poppy and cold mandrake juice,

And being asleep, belike they thought me dead,

And threw me o’er the walls.

Du Bartas, as translated by Sylvester in 1592, makes the following

allusion to anæsthesia:--

Even as a surgeon minding off to cut

Som cureless limb; before in use he put

His violent engins in the victim’s member,

Bringeth his patient in a senseless slumber:

And griefless then (guided by use and art)

To save the whole, saws off the infested part.

Porta, writing in 1579, says: “It is possible to extract from

several soporific plants a quintessence, which is to be shut up in a

well-covered leaden vessel, lest the drug should evaporate. When it is

to be used, the lid is to be removed and the medicament held to the

nostrils, when its vapour will be drawn in by the breath and attack the

citadel of the senses, so that the patient will be sunk in a deeper

sleep not to be shook off without much labour.”

[Illustration: A SURGEON PERFORMING AN OPERATION ON THE EYE

From a woodcut of the XVII century]

Besides mandragora, opium, Indian hemp, and other plants with narcotic

properties already referred to, that were used for anæsthetic purposes

in mediæval times, certain substances are mentioned by early writers

that cannot be identified. Thus Albertus Magnus mentions an animal

product, of which he says: “Any person smelling it falls down as if

dead and insensible to pain,” but there is no reference to such a drug

by other writers of the period.

[Sidenote: Local anæsthetics in antient times]

Local anæsthesia was not unknown during the middle ages, and Cardow

recommends the inunction of a mixture consisting of “opium, celandine,

saffron, and the marrow and fat of man, together with oil of lizards.”

He also adds: “If the patient drinks wine in which the seeds of the

patulica marina have been steeped for a week, it will prevent him

feeling any pain.”

[Sidenote: First mention of freezing as an anæsthetic]

Bernard mentions that it was customary in Salerno to mix the crushed

seeds of poppy and henbane, and apply them as a plaster, to deaden

sensibility, to parts that were about to be cauterised; while

Bartolinus states that local anæsthesia was sometimes produced by

freezing, thereby foreshadowing the use of ether and ethyl chloride as

local anæsthetics.

[Sidenote: Boerhaave’s anæsthetic]

During the seventeenth century the belief in the narcotic draughts of

the antients for producing anæsthesia appears to have waned, and few

allusions are made to them until the middle of the eighteenth century,

when fresh interest seems to have been excited in the subject. The

famous Boerhaave is said to have used opium as an anæsthetic, both

by inhalation of its vapour and also by internal administration in

powder. According to Van Swieten, in his commentaries upon Boerhaave’s

“Aphorisms,” the following is given as the recipe: “Oil of cinnamon, 2

drops; oil of cloves, 1 drop; citron peel, 2 grains; sugar, 2 drachms.

Mix and add red coral, prepared, 1 drachm; pure opium, 2 grains. Mix

for two doses, one of which is to be taken one hour before the

operation, and the other one quarter hour before it, if the patient has

not slept.”

[Illustration: AN OPERATION IN THE SEVENTEENTH CENTURY

From a painting by Franz Hals]

[Sidenote: An operation on the King of Poland]

In 1782, Weiss is said to have operated on the foot of Augustus,

King of Poland, having previously placed the royal patient under the

influence of “a certain potion surreptitiously administered.” Shortly

afterwards Sassard, a surgeon of La Charité, in Paris, suggested

that patients who were about to be operated upon should be drugged

with narcotics as a means of preventing shock. That this method was

sometimes practised is evidenced from a chapter in “Bell’s Surgery,”

where the author not only refers to it but objects to the method on

account of the sickness and vomiting it produced.

As late as 1847, Chisholm, of Inverness, recorded his use of a drug

given internally to produce anæsthesia for surgical purposes; he

substituted the internal use of morphine for ether inhalation in a case

of ablation of the breast successfully performed upon a woman, who

declared that she felt no pain during the operation.

[Sidenote: Anæsthesia by compression of the carotid arteries revived]

Other means of producing insensibility were suggested in the eighteenth

century, and the antient method of compressing the carotid arteries was

revived. This method had been used by Valverdi about 1560, and Morgagni

employed it about 1750 in his experiments on animals, and suggested

that it might be used on human beings. Compression of the nerves of the

limb about to be removed, was also proposed, by James Moore in 1784,

and tried by Hunter and others, but the results could not be regarded

as successful.

[Sidenote: Nelson’s arm amputated]

Surgical operations at this time meant periods of agonising pain, and

the stoutest hearts often quailed at the prospect. It is said that Lord

Nelson was so painfully affected by the coldness of the operator’s

knife when his right arm was amputated at Teneriffe, that at the Battle

of the Nile he gave orders to his surgeon to have hot water kept

ready, so that at the worst he might be operated upon with a warm knife.

[Sidenote: The dawn of a new era]

Thus from the dawn of creation anæsthesia for surgical operations

had been practised to some extent, but, owing to the uncertainty of

the potency and action of the powerful narcotics and palliatives

administered, and the danger attending their use when exact science was

unknown, the practice seemed likely to fall into oblivion. At last a

series of brilliant discoveries in chemistry created a new epoch in the

history of anæsthesia.

THE CHEMICAL ERA OF ANÆSTHETICS

[Sidenote: Priestley’s discoveries]

The discoveries of Priestley about 1767 led up to the plan of

administering gases and vapours of definite composition by inhalation

through the lungs, and directly he had demonstrated the existence of

“vital air,” or oxygen, the properties of this body were tested in the

hope of great results in the art of medicine. Priestley’s experiments

concerning the inhalation of oxygen were in time followed by those

of Beddoes, who recommended the inhalation of oxygen, hydrogen and

other gases in the treatment of disease. It seemed only natural that

experiments with other gases and vapours by inhalation should follow.

Pearson, of Birmingham, administered ether in this way in 1795 for the

relief of consumption, and ten years afterwards Warren, of Boscombe,

employed ethereal inhalation to relieve the sufferings attending the

later stages of phthisis.

Priestley’s discoveries of the method of liberating and collecting

gases, and his demonstrations that certain gases could be absorbed

and compressed in water, led to the introduction of aërated

waters--carbonic acid gas being the first to be employed.

[Illustration: JOSEPH PRIESTLEY]

In the course of time, nitrous oxide, which had been discovered by

Priestley in 1776, was compressed in water, and came into general

use as a medicinal agent.

[Sidenote: Anæsthetic properties of nitrous oxide]

In 1798, a Medical Pneumatic Institution was established at Bristol by

the exertions of Beddoes and others, and Humphry Davy was appointed

superintendent. It was here that he commenced and carried on his

notable researches on nitrous oxide. In one of his experiments he

constructed a box or chamber in which he inhaled the gas in measured

quantities. One day, in the year 1799, when suffering from toothache

or inflammation of the gums, he resorted to the inhalation of the

gas, and discovered to his great delight that it relieved the pain,

which led him to the conclusion he expresses in the following words in

“Researches Chemical and Philosophical,” 1800: “As nitrous oxide in its

extensive operation seems capable of destroying physical pain, it may

probably be used with advantage during surgical operations in which no

great effusion of blood takes place.”

[Illustration: SIR HUMPHRY DAVY]

[Sidenote: Faraday points out similarity in the effects of nitrous

oxide and sulphuric ether]

About 1806, Woolcombe, of Plymouth, prescribed for Lady Martin, a

patient suffering from asthma, the inhalation of sulphuric ether

to relieve the attacks. Lady Martin found the inhalation gradually

caused her to become unconscious, from which state she would recover

in a short time, with the result that the paroxysm of dyspnœa had

disappeared. But the teaching of this case, and even the more explicit

account of Humphry Davy, was overlooked; and no further development

occurred until the year 1818, when Faraday pointed out, in “The

Quarterly Journal of Science and Arts,” that the inhalation of the

vapour of sulphuric ether produced effects similar to those caused by

nitrous oxide.

[Illustration: MICHAEL FARADAY]

About this time Professor Thompson, of Glasgow, was accustomed annually

to amuse his students by allowing them to inhale ether and nitrous

oxide until they were intoxicated, and occasionally became unconscious,

when it was noticed that they were insensible to the prick of a pin,

or a blow. In these cases the gas or ether was inhaled from a bladder.

Two drachms of rectified and washed ether were poured into a bladder

and allowed to diffuse. Then the mixture of air and ether vapour was

breathed, the expired air being allowed to enter the bladder also.

Curiously enough, very little improvement has been made on this method

of administration to the present day.

[Sidenote: On the brink of the discovery]

It is an extraordinary fact that, even in the face of such experiments

as those we have referred to, no one among the investigators who stood

at this time on the brink of so great a discovery ventured over the

threshold. It is almost inconceivable in these days to realise, that

for thirty-nine years these substances were used for experimental

purposes, and even for amusement, without a realisation of the great

blessing to humanity that lay almost within grasp. The things that are

apparently most plain may lie longest buried; so with the discovery of

efficient anæsthesia, which even then developed in an indirect manner.

MESMERISM AS AN ANÆSTHETIC

[Sidenote: Mesmerism in antient times]

[Sidenote: Healing by “stroking”]

From the earliest ages the apparent power of some men to influence

the minds and bodies of others has been known. Certain diseases were

said to be affected by the touch of the hand of certain persons,

who were supposed to communicate a healing virtue to the sufferer,

and these practices were often connected with religious and magical

rites. This method of healing was practised in antient times by the

Chaldæans, Babylonians, Egyptians, Persians, Hindus, Greeks and Romans.

Their priest-physicians are said to have effected cures and to have

thrown people into deep sleep in the precincts of the temples. Such

influences were at that time held to be due to supernatural power, a

belief which was no doubt fostered by the priesthood. In the middle

of the seventeenth century an Irishman named Valentine Greatrakes

aroused great interest in England by his supposed power of being able

to cure scrofula by stroking the patient with his hand. Most of the

distinguished scientific men of the day, such as Sir Robert Boyle,

witnessed and attested his cures, and thousands of sufferers crowded

to him from all parts of the country. Since his time other men have

come forward with similar claims, notably one Gassner, a Roman Catholic

priest of Swabia, who in the early part of the eighteenth century

attracted attention by stating that he could cure the majority of

diseases by exorcism. His method had an extraordinary influence over

the nervous systems of his patients, who in the end generally confessed

themselves cured.

[Sidenote: Mesmer’s experiments]

In 1766, Mesmer, who was a pupil of Hehl, professor of astronomy at

Vienna, and an advocate of the efficacy of the magnet for the cure

of disease, met Gassner, and observed that the priest effected cures

without the use of magnets and by manipulation alone. This led him to

believe that some kind of occult force resided in himself, by means of

which he could influence others. He held that this force permeated the

universe, and more especially affected the nervous systems of men. In

1778, he removed to Paris, and shortly afterwards the French capital

was thrown into a state of great excitement by the fact that human

beings could be placed in a state of artificial sleep or trance, which

was then called “mesmerism.”

Mesmer’s disciples claimed that even painful operations could be

performed on patients in this condition without consciousness of pain.

[Sidenote: Braid’s researches on hypnotism]

[Sidenote: Esdaile operates on hypnotised patients]

Braid, who made a further investigation of the subject, dissented

from the mesmerists as to the cause of the phenomenon, and called the

condition “hypnotism.” In 1846, the Deputy-Governor of Bengal appointed

a committee to observe and report on the surgical operations that

were then being performed in India by Esdaile upon his patients, while

under the influence of alleged mesmeric agency. The Committee reported

on various experiments carried out under their observation, some of

which had apparently been performed with great success. But from

further investigation it was apparent that the method was uncertain,

and success seemed to be due to the peculiar susceptibility of the

patient operated upon. These experiments are worth recording, as they

indirectly led to the practice of administering certain vapours to

produce anæsthesia.

[Sidenote: Robert Collier one of the first pioneers]

One of the pioneers in the practice of inhalation was Robert H.

Collier, who was a believer in mesmerism. In 1835 he was present at

a lecture given by Dr. Turner, Professor of Chemistry at University

College, London, and in the course of some experiments in the

inhalation of ether was himself rendered unconscious, and also observed

that his fellow-students who had inhaled it were insensible to pain.

Four years later he went to America, and, while visiting his father’s

estate near New Orleans, he was called to one of the negroes who had

become insensible by inhaling fumes from a vat of rum, and who, in

falling, had dislocated his hip. Finding the muscles flaccid, Collier

reduced the dislocation without exciting the least sensation of pain in

the patient. A little later he performed two operations upon patients

while under mesmeric influence, with apparent success. These facts led

him to connect the phenomenon of mesmerism with narcotism produced

by inhalation, and in 1840 he commenced a lecturing tour throughout

America on the subject. Three years later he returned to this country,

and at Liverpool, where he landed, gave his first lecture, which

he illustrated by experiments in mesmerism, and also showed the

possibility of rendering a subject unconscious by the fumes of alcohol

in which poppy-heads and coriander had been macerated. The theory he

advanced, and attempted to prove throughout, was that the so-called

mesmeric influence was identical in action with that of narcotic

vapours.

[Sidenote: Uses his alcoholic mixture as an anæsthetic in 1842]

He claimed to have administered the fumes of his alcoholic mixture to a

Mrs. Allen, of Philadelphia, in 1842, and while under its influence he

extracted a tooth without causing her pain. Collier’s lectures excited

general attention at the time, and there is little doubt that they gave

a fresh impetus to research on the subject of anæsthesia by inhalation.

He must therefore be regarded as an important pioneer, who, had he

given up his ideas of mesmerism and proceeded systematically with his

plan of making the body insensible by inhaling the vapour of alcohol,

would have had no one to dispute with him in priority.

THE NITROUS OXIDE ERA

Although, as already stated, Humphry Davy had discovered the anæsthetic

properties of nitrous oxide as far back as the year 1800, forty-four

years elapsed before his idea was put into practical use.

[Sidenote: Colton lectures on nitrous oxide]

On December 11th, 1844, Dr. G. Q. Colton, a well-known lecturer on

popular scientific subjects in America, and a pupil of Professor

Turner, of London, delivered a lecture at Hartford, Connecticut, during

which he gave a demonstration of the action of nitrous oxide gas.

Horace Wells, a dentist, then in practice in the same town, formed one

of the audience.

[Illustration: HORACE WELLS]

[Sidenote: Wells makes his historic experiment]

Among the persons who were invited by the lecturer to inhale the gas

for the amusement of the audience was a man named Cooley, who wounded

himself severely by falling against the benches, and only became aware

of the fact when he saw the blood. Wells was greatly struck by this

incident, and he determined to test the anæsthetic effects of the gas

upon himself the next day by having a decayed upper molar extracted

while under its influence. After the lecture he asked Dr. Colton if

he would come to his house and administer the gas to him; and, on

receiving his promise, he induced a Dr. Riggs to be the operator.

The historic event is described by the latter as follows: “A few

minutes after I went in, and, after conversation, Dr. Wells took a seat

in the operating chair. I examined the tooth to be extracted, with a

glass, as I usually do. Wells took a bag of gas from Dr. Colton and sat

with it in his lap, and I stood by his side; he then breathed the gas

until he was much affected by it: his head dropped back, I put my hand

to his chin, he opened his mouth, and I extracted the tooth. His mouth

still remained open some time. I held up the tooth with the instrument

that the others might see it; they, standing partially behind the

screen, were looking on. Dr. Wells soon recovered from the influence of

the gas so as to know what he was about, discharged the blood from his

mouth, and said, ‘A new era in tooth-pulling!’ He said it did not hurt

him at all. We were all much elated, and conversed about it for an hour

later.”

[Illustration: “A NEW ERA IN TOOTH-PULLING”

The first dental operation performed on Horace Wells whilst under the

influence of nitrous oxide gas]

[Sidenote: “A new era in tooth-pulling”]

After this, Wells extracted several teeth from his patients under

nitrous oxide gas with equal success, and then went to Boston in order

to make his discovery known to the medical profession in that city.

He remained there some days in the hope of being allowed to try the

gas in a case of amputation in the Massachusetts General Hospital,

but the experiment was postponed. Dr. Warren, senior surgeon to the

institution, however, invited him to address his class on the subject

of anæsthesia, after which he was asked to administer the gas in a case

of tooth extraction. He was assisted on this occasion by Morton, a

Boston dentist who had been his pupil, and afterwards, for a time, his

partner. The experiment, as Wells himself confesses, was not quite a

success, the gas-bag having been removed too soon. The whole thing was

denounced as a piece of humbug, and Wells was hissed out of the room as

an impostor.

[Sidenote: Wells disheartened by failure]

[Sidenote: The death of Horace Wells]

Disheartened at length by the failure of his repeated attempts to

establish his claims to priority as the discoverer of anæsthesia, his

mind appeared to become affected, and for a time he wandered about the

streets of New York. On January 4th, 1848, he was arrested and charged

with throwing vitriol, but while in gaol he opened his radial artery,

having first inhaled ether to make death painless. This sad event

closed, at the age of thirty-two, the career of Horace Wells, to whom

at least belongs the credit of having first shown the practicability of

producing insensibility by nitrous oxide, and of having thus, in his

own words, “established the principle of anæsthesia.”

THE ETHER EPOCH

Probably the first published account of the use of ether as a medicinal

agent was made by Morris in a letter read before the Society of

Physicians in London,[1] on December 18th, 1758, in which he advocates

its use internally, and also as an external application.

[1] “Med. Obs. and Enq.” by the Society of Physicians in London, vol.

2, page 176, 1764.

In 1818, Faraday, as already stated, had called attention to the

anæsthetic properties of ether, and showed that the vapour of sulphuric

ether, when inhaled, produced effects similar to those of nitrous

oxide. After Wells’ failure at Boston nothing further seems to have

been done for a time to investigate the use of nitrous oxide as an

anæsthetic.

[Sidenote: Early experiments with ether]

In 1839, William E. Clarke, a young medical student of Rochester, New

York, was in the habit of amusing some of his friends, among whom was

another student named W. T. G. Morton, by the inhalation of ether.

Emboldened by his experiences, in 1842 he is said to have administered

ether, by means of a towel, to a young woman named Hobbie, and

during the period of insensibility which followed, one of her teeth was

extracted by a dentist named Elijah Pope.

J. Marion Sims relates the following incident which he states happened

in the year 1839:--“A number of youths in Anderson, South Carolina,

were exhilarating themselves one day with the seductive vapour of

ether. In their excitement they seized a young negro who was watching

their antics, and compelled him to inhale the drug from a handkerchief

which they held over his mouth and nose by main force. At first his

struggles only added to the amusement of his captors, but they soon

ceased as the boy became unconscious, stertorous and apparently

dying. After an hour or two of anxiety on the part of the spectators

he, however, revived, and was apparently no worse for his alarming

experience.”

[Sidenote: Long claims to have used ether in 1842]

Three years after this incident one of the participators in the affair,

named Wilhite, became the pupil of Dr. Crawford W. Long, a physician

then practising in Jefferson, Jackson County, Georgia. Both the doctor

and his pupils used occasionally to amuse themselves by inhaling ether,

and the former often noticed that while thus excited he was insensible

to blows and bruises. Wilhite recounted to him his memorable experience

with the negro boy; and, in March, 1842, Long is said to have persuaded

a patient, on whom he was about to operate for a small encysted tumour,

to inhale ether until he was insensible. The patient consented, and

the tumour was removed without any pain or accident. This memorable

event was simply recorded by Long in his ledger thus:--“James Venable,

1842. Ether and excising tumour, $2.00.” Three months later he removed

another tumour from the same patient in a similar way, and also

performed three other operations during that year. He is said to have

again repeated the experiment in 1843 and 1845, but the district in

which he lived was so far removed from contact with the large cities

and centres of thought, that the discovery remained unknown and

unpublished until long after the anæsthetic properties of ether had

been fully proved elsewhere. Long himself admits that he considered

ether impracticable owing to the shortness of the anæsthetic state, and

he therefore abandoned its use.

[Sidenote: Marcy’s experiment]

Towards the end of the year 1844, Dr. E. E. Marcy, a surgeon of

Hartford, is said to have administered ether to a patient, and to have

removed an encysted tumour about the size of a walnut from the scalp.

It is stated that Horace Wells was present at this operation, which was

quite successful, but, being warned that ether was dangerous to life,

the experimenters abandoned its use in favour of nitrous oxide gas.

[Sidenote: Morton’s experiments with ether]

In 1846, W. T. G. Morton (referred to previously) who had been

in partnership with Wells as a dentist, and assisted him in the

unfortunate experiment with nitrous oxide in Boston, now directed his

attention to the finding of a more suitable anæsthetic for painless

operations in dental surgery. After many unsuccessful attempts with

various narcotics, Charles T. Jackson, a chemist of Boston, whose

pupil he had been, suggested that he should try sulphuric ether, the

properties of which had been known for so long.

[Illustration: CHARLES T. JACKSON]

[Sidenote: Jackson’s story]

It was about the end of September, 1846, that Jackson states he

informed Morton that he had experimented on himself by inhaling ether

on a folded towel. He found that he lost all power over himself, and

fell back in his chair in a state of curious sleep. Morton, however,

tells another story, and relates how, having procured some chemically

pure ether on September 30th, 1846, he shut himself in a room alone and

inhaled the vapour. He states: “I found the ether so strong that it

partly suffocated me, but produced no decided effect. I then saturated

my handkerchief and inhaled it from that. I looked at my watch and soon

lost consciousness. As I recovered I felt a numbness in my limbs, and

a sensation like nightmare. I thought for a moment I should die in

that state, but at length I felt a slight tingling of the blood in the

end of my third finger, and made an effort to press it with my thumb,

but without success. At the second effort I touched it, but there

seemed to be no sensation. I attempted to rise from my chair, but fell

back, and looked immediately at my watch and found that I had been

insensible between seven and eight minutes.”

THE FIRST DENTAL OPERATION UNDER ETHER

Morton soon had an opportunity of making a practical experiment with

the anæsthetic, for the same evening, about nine o’clock, a man

named E. H. Frost called upon him suffering from a violent attack of

toothache. “Can’t you mesmerise me?” asked the sufferer. “Upon which,”

says Morton, “I told him that I had something better than mesmerism by

means of which I could take out his tooth without giving him pain. He

gladly consented, and saturating my handkerchief with ether, I gave

it to him to inhale. He became unconscious almost immediately. It was

dark, and Dr. Hayden held the lamp. My assistants were trembling with

excitement, apprehending the usual prolonged scream from the patient

while I extracted a firmly-rooted bicuspid tooth. I was so agitated

that I came near throwing the instrument out of the window. But now

came a terrible reaction. The wrenching of the tooth had failed to

rouse him in the slightest degree. I seized a glass of water, and

dashed it in the man’s face. The result proved most happy. He recovered

in a minute, and knew nothing of what had occurred.”

[Sidenote: First surgical operation under ether]

Morton next appealed to Dr. John C. Warren, who was then Senior Surgeon

at the Massachusetts General Hospital, and obtained permission to test

his new anæsthetic on a patient about to undergo a surgical operation.

The date fixed was Friday, October 16th, 1846, and at the appointed

time a large number of medical men had assembled in the theatre. Morton

administered the anæsthetic successfully, and the operation, which was

for a congenital vascular tumour of the neck, in a young man named

Gilbert Abbot, was completed in about five minutes without a groan from

the patient. When it was finished, Dr. Warren exclaimed: “Gentlemen,

this is no humbug!” The interest excited amongst those who witnessed

the operation was naturally very great, and Dr. Henry J. Bigelow, who

was present, said to a friend whom he met later in the day: “I have

seen something to-day that will go round the world!” His prophecy

proved correct.

Up to this time Morton had not disclosed the nature of the agent

he employed, and nothing more was done until November 7th, when he

expressed his willingness to reveal the secret. On this date two major

operations were performed under ether, one by Dr. Hayward and the other

by Dr. Warren.

From this time ether took its place as a general anæsthetic, and the

practice of anæsthesia was firmly established.

[Sidenote: The origin of the words “anæsthesia” and “anæsthetic”]

Soon after the memorable 16th of October, a meeting was held in

Boston, to choose a name for the new anæsthetic agent, and the word

“letheon” was chosen by Morton himself; but, subsequently, Dr. Oliver

Wendell Holmes suggested the name “anæsthesia” for the condition, and

“anæsthetic” for the agent, which names have since come into general

use.

Although it has never been very clearly established whether Morton

or Jackson was the prime originator of the use of ether as an

anæsthetic, the former was recognised by the United States Government

as the discoverer, and received from it a handsome award. It seems

most probable that Jackson supplied the inspiration, while Morton

practically demonstrated it.

[Illustration: W. T. G. MORTON]

In reviewing the steps which led up to the discovery, it must not be

forgotten that both Morton and Jackson were after all but followers

of Collier, who first rendered himself unconscious with ether in the

laboratory of University College, London, and forged one of the most

important links in the chain of development.

Morton spent most of the remainder of his life in disputes about

priority, and in efforts to secure recognition. He died bankrupt

and broken-hearted on July 15th, 1868, before he had completed his

forty-ninth year.

Curiously enough, Jackson, like Wells, became insane, and died in

an asylum in 1880. When the friends of the rival claimants of the

discovery of anæsthesia were proposing that monuments should be erected

to each, Oliver Wendell Holmes characteristically suggested that all

should unite in erecting a single memorial, with a central group

symbolising painless surgery, a statue of Jackson on one side, a statue

of Morton on the other, and the inscription underneath:--

TO E(I)THER

The news of the “ether process for removing pain,” as it was then

called, spread rapidly. A private letter from Dr. J. Bigelow to Dr.

Francis Boote, of Gower Street, carried the first news to England,

and was communicated to the medical profession in London on December

17th, 1846. Two days later, Mr. James Robinson, a dentist, of Gower

Street, performed the first dental operation under ether in England,

the patient being a Miss Lonsdale, and the operation the extraction of

a firm molar tooth.

On December 21st the first surgical operation under the new anæsthetic

in England was performed by Robert Liston, in University College

Hospital, London.

[Sidenote: First surgical operation under ether in Great Britain]

In the operating theatre, thronged with students, were the late Sir

John Erichsen, the present Lord Lister, and many other famous surgeons.

Mr. Barton relates an amusing incident which happened prior to the

operation. Before the patient was brought in, the anæsthetist asked the

students who crowded the benches in the theatre from floor to ceiling

for some volunteer who would submit himself to be anæsthetised. A

young man, Sheldrake, of very powerful build and a good boxer, at once

offered to take the new anæsthetic, and came into the arena. “He lay on

the table, and the anæsthetist proceeded to administer the ether. After

the administration had proceeded for about half a minute, the subject

of the experiment suddenly sprang up and felled the anæsthetist with a

blow, and, sweeping aside the assistants in the arena, sprang shouting

up the benches, scattering the students, who fled like sheep before a

dog. He fell at the top bench, where he was seized and held down till

he regained his senses. The whole scene hardly occupied a minute.”

[Illustration: An apparatus called “Letheon”

One of the earliest employed for the administration of Ether]

[Sidenote: New method of administration]

Before operating, Liston addressed a few words to those present as

to the nature of the experiment about to be tried. The ether was

administered by Mr. William Squire in an apparatus he had devised,

which consisted of a large bell-shaped receiver containing the ether,

to which was attached a long tube and mouthpiece. The patient, a

middle-aged man, who was suffering from malignant disease of the skin

and tissues of the calf of the leg, for which amputation of the thigh

was deemed necessary, passed easily into complete insensibility, and

Liston rapidly removed the thigh, the cutting operation being declared

to have lasted only thirty-two seconds. In a few moments the patient

completely recovered consciousness, and apparently did not know that

the limb was off. When the towel was removed from the uplifted stump so

that he could see it, he burst into tears and fell back on his pillow.

Both surgeon and patient were much affected, and the scene in the

theatre was most impressive. All appeared to see what an incalculable

boon was in store for the human race, and Liston could scarcely command

his voice sufficiently to speak.

[Sidenote: A story of Liston]

Some amusing stories are related of Liston, who was a very big,

powerful man. His fine physique was often useful in the pre-anæsthetic

days, when a patient’s nerve gave way at the last moment at the sight

of the crowded theatre and the operating-table with its straps. It is

said that on one occasion a patient, losing his courage at the last

moment, rushed shrieking down the long corridor of the hospital, with

Liston at his heels. The man locked himself in a room, but the surgeon

with his shoulder broke in the door, and half-dragged half-carried the

poor wretch back to the operating theatre, where the operation for

stone was successfully performed.

[Sidenote: First surgical operation under ether in Scotland]

The practice of using ether was soon followed in other hospitals,

and not only medical men but distinguished laymen crowded to witness

its use. In Scotland, Dr. Moses Buchanan, Professor of Anatomy in

Anderson’s University, was the first to have news of the event, and

immediately after his lecture that day he experimented with ether

inhalation. On the following day, in the operating theatre of Glasgow

Royal Infirmary, a patient was placed under the anæsthetic and

successfully operated on for fistula. So rapidly, indeed, did the

practice spread from one centre to another, that by the end of the

first quarter of 1847 the use of the new anæsthetic may be said to have

become general in all operation cases.

[Sidenote: Simpson proves value of ether in midwifery]

The value of ether in midwifery practice still remained to be proved,

and Sir James Simpson was the first to suggest and test its use in this

department. On January 9th, 1847, he first administered ether to a

patient in order to facilitate the operation of turning. The result, he

reported, was most satisfactory and important, for it at once afforded

evidence of the one great fact upon which the whole of the practice

of anæsthesia in midwifery is founded, viz., that though the physical

sufferings of the patient could be relieved by the inhalation of ether,

yet the muscular contractions of the uterus were not interfered with.

THE DISCOVERY OF CHLOROFORM AS AN ANÆSTHETIC

The next epoch-making event in the history of anæsthesia was the

discovery of the anæsthetic properties of chloroform. The substance

itself had been known for over a quarter of a century. Thomson, in

his “System of Chemistry,” 1820, describes a liquid which is formed

by the union of chlorine and olefiant gas, called “Dutch liquid,” or

chloric ether. Early in the year 1831, Samuel Guthrie of Brimfield,

Massachusetts, who was then residing in Sackett’s Harbour, New York

State, in consequence of a statement that he had read that the

alcoholic solution of this chloric ether was useful in medicine as a

diffusible stimulant, devised an easy method of preparing it. This

being done, he wrote an article which he entitled “A Spirituous

Solution of Chloric Ether,” and forwarded it to the editor of the

“American Journal of Science and Art,” in which it was published in

October of the same year. In this article he fully describes his

method of preparation. A few months later, in January, 1832, Soubeiran

published a paper in a French journal, stating that he had discovered

this method in 1831, and to the distilled fluid he produced he had

given the name of “bichloric ether,” the formula being CHCl. Still a

third claimant to the discovery came forward in the person of Liebig,

who published his account in November, 1831, six months after Guthrie’s

manuscript was in the publisher’s hands, and one month after its

publication. The formula which Liebig deducted from his analysis was

C_{4}Cl_{5}, and he called his product “chloride of carbon.” Although

there may be some doubt as to which of these claimants was actually the

first to manufacture the liquid, it is clear that Guthrie was the first

to publish the account of the discovery. He was born in 1782, was a

surgeon in the United States Army in 1812, and died in 1848.

From an account given by D. B. Smith, of Philadelphia, in the “Journal

of the College of Pharmacy”[2] in 1832, there can be little doubt that

the liquid first made by Guthrie was a fairly pure chloroform. He

describes it in the following words: “The action of this ether on the

living system is interesting, and may hereafter render it an object of

importance in commerce. Its flavour is delicious, and its intoxicating

properties equal to or surpassing those of alcohol.” In 1834, Dumas

examined the liquid as prepared by Soubeiran, and declared that he had

not obtained it pure, and further, that Liebig had made an error in its

composition. On further research, Dumas gave the liquid the name of

“chloroform,” and first worked out the real formula, C_{2}HCl_{3} (or,

using the present system of atomic weights, CHCl_{3}).

[2] Now the “American Journal of Pharmacy”

[Sidenote: Previous use of chloroform in medical practice]

Although its narcotising properties were known to some extent, no one

who used it at that time seems to have conceived the idea of fully

testing its properties. In 1831, Ives, of Newhaven, treated a case of

difficult respiration by actual inhalation of the vapour, and published

the facts in “Silliman’s Journal” in January, 1832. Four years later,

Dr. Formby, of Liverpool, prescribed it in hysteria; and Tuson, of

London, employed it in the treatment of cancer and neuralgia in 1844.

[Sidenote: Simpson’s investigations]

The fact that one or two deaths had been attributed to the use of

ether about this time, caused many workers to make a search for other

agents with similar properties. Foremost among these investigators was

Dr. James Young Simpson, Professor of Midwifery in the University of

Edinburgh, who personally experimented with several chemical liquids in

the hope of finding something less disagreeable and persistent in smell

than ether.

[Illustration: DAVID WALDIE]

[Sidenote: Waldie suggests the use of chloroform]

About this time, Jacob Bell, a chemist, and a founder of the

Pharmaceutical Society, published a suggestion that chloric ether

should be used for inhalation instead of sulphuric ether; but his

suggestion was apparently never put into practice. In October, 1847,

Waldie, a chemist of Liverpool, was visiting Edinburgh, and in

conversation with Professor Simpson, suggested to the latter the use of

chloroform. He recommended the Professor to try it as an anæsthetic,

and promised to make and send him some on his return to his home in

Liverpool.

[Illustration: SIR JAMES YOUNG SIMPSON]

It appears to have been in that city that the drug was first introduced

and probably first used in England as a medicinal agent. Waldie

states that about the year 1838 a prescription was brought to the

Apothecaries’ Hall, Liverpool (where he held the position of manager),

of which one of the ingredients was chloric ether. The preparation was

at that timen apparently not known in this country, for Dr. Brett,

the chemist of the Company, specially prepared some from the formula

he found in the United States Dispensatory. Its properties pleased

some of the medical men, particularly Dr. Formby, by whom it was

introduced into local practice. Waldie, finding that the preparation

was not uniform in strength, improved the process by separating and

purifying the chloroform, and dissolving it in pure spirit, by which a

product of sweet flavour was obtained.

[Sidenote: On the eve of the great discovery.]

There seems little doubt that Waldie was the first to suggest the use

of chloroform, as an anæsthetic, to Professor Simpson, who at once

resolved to try it by experimenting on himself and his assistants. He

made the first experiment in his own house on November 4th, 1847, and

in a letter written to Waldie thus describes the event: “I am sure

you will be delighted to see part of the good results of our hasty

conversation. I had the chloroform for several days in the house before

trying it, as, after seeing it such a heavy, unvolatile-like liquid,

I despaired of it, and went on dreaming about others. The first night

we took it, Dr. Duncan, Dr. Keith and I all tried it simultaneously,

and were all ‘under the table’ in a minute or two.” Professor Miller,

who was a neighbour of Simpson’s, used to come every morning to see

if the experimenters had survived! He describes how, “after a weary

day’s labour, Simpson and his assistants sat down and inhaled various

drugs out of tumblers, as was their custom. Chloroform was searched

for and found beneath a heap of waste paper, and with each tumbler

newly charged the inhalers resumed their occupation. . . . A moment

more, then all was quiet; then a crash. On awakening, Simpson’s first

perception was mental. ‘This is far stronger and better than ether,’

said he to himself. His second was to note that he was prostrate on the

floor, and that among the friends about him there was both confusion

and alarm. Of his assistants, Dr. Duncan he saw snoring heavily, and

Dr. Keith kicking violently at the table above him. They made several

more trials of it on that eventful evening, and were so satisfied with

the results that the festivities did not terminate until a late hour.”

[Sidenote: Simpson achieves success]

On November 10th, 1847, Simpson communicated his discovery to the

Medico-Chirurgical Society of Edinburgh, in a paper entitled, “Notice

of a new anæsthetic agent as a substitute for sulphuric ether.” A day

or two afterwards an arrangement was made with Simpson to administer

the new anæsthetic to a patient who was about to be operated upon,

but, owing to some cause, he was unable to be present. The operation

went on without him, and the patient died on the first incision of the

knife. Simpson’s absence was providential indeed, for it saved the

reputation of chloroform at the outset. On November 15th, chloroform

was used for the first time in a surgical operation in the Edinburgh

Royal Infirmary. Three patients were operated on successfully under its

influence. One, who was a soldier, was so delighted with the effect

that, on awaking after the operation, he is said to have seized the

sponge with which administration had been made, and, thrusting it into

his mouth, again resumed inhalation more vigorously than before.

To Simpson, there is no doubt, belongs the merit of having made

anæsthesia triumph over all the opposition, which was at first,

actively, offered to its use. For this he well deserved the rewards

which fell upon him in the evening of his life.

Among those who aided in the establishment of the use of anæsthetics,

mention must be made of the work of John Snow, who by his researches

placed the practice on a scientific basis.

The advent of chloroform gave an impetus to other investigators in the

field of anæsthesia, and during the last fifty years many other bodies

have been introduced and tried with more or less success for the same

purpose. Methyl chloride, which was discovered by Dumas and Peligot,

was introduced by Deboe in 1887, who used it extensively in local

affections. In 1867, Sir B. W. Richardson introduced methyl bichloride

or methylene [methylene dichloride]. He formed a very high estimate of

its properties as a good general anæsthetic, and said he preferred it

for many reasons to chloroform, as he found that the anæsthetic sleep

was produced more quickly and was more prolonged.

Sir T. Spencer Wells also advocated its use, and stated, in 1872, that

it had fewer drawbacks than any then known anæsthetic. Tetra-chloride

of methyn [carbon tetrachloride], which much resembles chloroform,

was discovered by Regnault in 1839, and its anæsthetic properties

were first made known by Sansom and Harley in 1864. Simpson was of

the opinion that it had a more depressing effect upon the heart than

chloroform, and was more dangerous generally as an anæsthetic.

Nunneley, of Leeds, also contributed work of value in this department

of research, and introduced ethyl bromide and chloride of carbon. He

dispelled the idea, long prevalent, that anæsthetics could be found

only in a limited class of chemical compounds.

Among other substances which have been introduced during the last

twenty-five years, but which, owing to one defect or another,

have since been practically abandoned, mention should be made of

butylic hydride [butane], ethylene, amylene, ethyl nitrate, aldehyde

(introduced by Poggiale), carbon bisulphide, ethidene dichloride

[ethylene dichloride] (discovered by Regnault and first used as an

anæsthetic by Snow), and ethyl bromide, first prepared by Serullus in

1827.

LOCAL ANÆSTHETICS

Local anæsthesia, already alluded to as probably the earliest form of

numbing sensibility to pain, was practised in antient times by the

inunction of various narcotics, but after the seventeenth century the

practice seems to have almost entirely gone out of use. The latter end

of the nineteenth century, however, marks a new era in this department.

On September 15th, 1884, considerable interest was aroused by a

communication made at the Ophthalmological Congress at Heidelberg, by

Karl Koller, of Vienna, in which he demonstrated the effects of cocaine

as a local anæsthetic.

[Sidenote: The discovery of Cocaine]

The alkaloid now known as cocaine was isolated by Gädeke, from the

leaves of the _Erythroxylon Coca_ as far back as 1855. He called

it ethroxylene. Four years later a further investigation of the plant

was made by Nieman, who noticed that the leaves produced a numbness

of the tongue; and in 1874 Hughes Bennett demonstrated that cocaine

possessed anæsthetic properties. In 1880, Von Anrep, who made a careful

investigation of the drug, hinted that the alkaloid might be of use in

general surgery as a local anæsthetic, and Koller undertook a series

of experiments on animals in the laboratory of Professor Stricker, in

which he found that complete anæsthesia of the eye, lasting, on an

average, ten minutes, followed the introduction of a two per cent.

solution of the alkaloid.

The immense value of such an anæsthetic in ophthalmic operations

was universally recognised, and it at once came into general

use. In painful conditions of mucous surfaces, and for minor

operations, cocaine has been found of great service, and as a

local anæsthetic it has a large field of usefulness. Since the

introduction of cocaine, other substances have been brought forward,

which, after extensive trials, have proved to be of real clinical

value. Of these may be mentioned eucaine, a synthetic product

(benzoyl-vinyl-diaceton-alkamine) discovered by Merling, and first

studied by Vinci in Liebreich’s laboratory. Of the two forms of this

drug used, which are known as A and B, the latter was soon found to be

the only one suitable for producing local anæsthesia. Its properties

are similar to those of cocaine, with the exception that it produces

no vaso-constriction, and it is claimed that it is equal in anæsthetic

power, whilst its toxicity is very much less.

[Sidenote: Stovaine and Tropa-cocaine]

Stovaine, or benzoyl-ethyl-dimethylaminopropanol hydrochloride, more

recently introduced, is a synthetic product elaborated by Fourneau, and

derived from tertiary amyl alcohol. It is much less toxic than cocaine,

but its comparative value still remains to be proved by further trial.

Tropa-cocaine, a drug closely allied to cocaine, and derived from the

leaves of the Java coca plant, has recently been much used in Germany,

but it does not appear to possess any advantages over cocaine or

eucaine.

Novocaine, or para-amido-benzoyl-diethylamino-ethenol hydrochloride,

has lately been found to possess satisfactory properties as a local

anæsthetic in dental operations. It is said to be free from the toxic

and local irritant action common to other local anæsthetics.

THE NECESSITY FOR ABSOLUTE PURITY IN CHLOROFORM

[Sidenote: Administration of Chloroform]

[Sidenote: Purity an essential]

[Sidenote: Danger of impurities]

Considerable attention has been directed to different methods of

administering chloroform, and various forms of apparatus have been

devised which claim to reduce to a minimum the dangers of anæsthesia.

Assuming a most skilled and competent administrator, an ideal method of

administration, and a suitable patient, an unsatisfactory result can

only be attributed to the chloroform employed. Purity of chloroform

is a most important factor in contributing to safe anæsthesia. The

physician claims that absolute purity shall characterise all medicinal

agents, and the justice of the claim is acknowledged by the trend of

recent legislation. Purity is a prime essential of any anæsthetic.

The presence of impurities largely increases the risk inseparable

from the use of chloroform. The train of symptoms observed during the

normal process of anæsthesia may be masked and altered, and dangerous