*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK 75337 ***

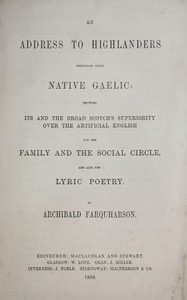

AN

ADDRESS TO HIGHLANDERS

RESPECTING THEIR

NATIVE GAELIC:

SHOWING

ITS AND THE BROAD SCOTCH’S SUPERIORITY

OVER THE ARTIFICIAL ENGLISH

FOR THE

FAMILY AND THE SOCIAL CIRCLE,

AND ALSO FOR

LYRIC POETRY.

BY

ARCHIBALD FARQUHARSON.

EDINBURGH: MACLACHLAN AND STEWART.

GLASGOW: W. LOVE. OBAN: J. MILLER.

INVERNESS: J. NOBLE. STORNOWAY: MACPHERSON & CO.

1868.

GENTLEMEN OF THE PRESS,

Aware of your great powers, I stand before your bar to plead, that ye

may plead for my countrymen, that they may be taught first to read their

mother tongue, which would not only be the most rational, but also the

most natural way of teaching them.

What an encouragement would it be to children to find their mother tongue

in their lessons—the very words they heard from her lips and their

playmates. How different from groping their way in the dark, in reading a

language they know nothing about. In the former case their judgment would

not only be in exercise, but would also assist and help to keep them

right; whereas in the latter case their judgment would give them no aid,

the whole depending upon their memory.

Were they thus taught first to read the Gaelic, and then to commence with

the English alphabet and the English pronunciation, and when reading,

to translate every word into Gaelic, it would not only exercise their

memory, but their judgment also, and encourage them to persevere, seeing

they were enabled to master the difficulties, being aided by one another

as well as by the teacher.

Is there no native Scotchman also that will stand at your bar to plead

for his mother tongue? Is that not the tongue, gentlemen, that many of

you heard from your mother’s lips, and that soothed you in the days of

your childhood? And ought you not to have the natural instinct to plead

for it yourselves?—to plead that the Broad Scotch should be the first

language taught in every part of Scotland, except where the Gaelic is

spoken; and when they could read their mother tongue, to commence at once

with the English alphabet and the English pronunciation, and when reading

it to translate every word into broad Scotch, such as _have_, hae; _so_,

sae; _of_, o’; _with_, wi, &c.

Before the time of the singing of birds shall ever dawn upon Scotland,

the Scotch must not only return to their native tongue but to their

native melodies also. Is it not a fact that there are no songs listened

to in the city of London with so much pleasure as the Scotch. I would

not be surprised although the native language and the native melodies of

Scotland are destined to give songs of praise to every part of the world

where the English language is spoken.

ADDRESS TO HIGHLANDERS.

MY FELLOW-COUNTRYMEN,

I lately considered it my duty to address the Highland Proprietors on

a subject which has been most painful to us all, namely, on “Highland

Clearances,”[1] and the same spirit which urged me to write that address,

urges me to write the present. A lover of my country I am, and ever have

been; and if there is anything more than another that is peculiar to my

native country which I love, it is the language. It was the language that

gave us a name, and that made us to differ from the rest of Scotland. If

there is anything more than another that makes me feel proud as a man,

it is this: that the Gaelic is my native tongue, and the Highlands of

Scotland my native country. A language more glittering with a refined

imagination than the former, and a country more glittering with the same

than the latter, in the names given to the different places, is not, I

believe, to be found on earth. I am also a great lover of the native

melodies of my country. I am aware that many of a serious turn of mind,

not putting a distinction between songs and the melodies accompanying

them, have been led to look upon them as something bad, calling them

cursed songs and cursed bagpipes. But they might as well call the

Gaelic by the same name, because wicked men use it for a bad purpose.

The Gaelic may be used for a good purpose, and so may these beautiful

melodies. There are many who use instruments of music in their parlours

for a good purpose, and why might not the bagpipes be used in the same

way? Any music that surpasses the melody of the bagpipes, in a Highland

glen, resounding from rocks, I have never listened to. I am sorry that

the old beautiful melodies of the Highlands are only to be found now, in

most places, amongst the aged, and that the young race have lost them

almost entirely. As the friend of our race, I would say to them: Gather

them all up, that none of them be lost. You can scarcely leave a better

inheritance for your children. I would willingly part with everything I

have in the world to be in possession of them.

Do not suppose that when a man becomes a Christian he ceases to be a

patriot—a lover of his country. No doubt he ceases to be a lover of

everything sinful peculiar to his countrymen, but I have no idea of

that religion that would make a man cease to be a man. Did the great

Apostle of the Gentiles ever forget that he was a Hebrew of the Hebrews?

No doubt he renounced it as the foundation of his hope before God,

but to the latest day of his life he never forgot it. The highest

degree of patriotism that ever existed in the soul of man existed in

his great heart. Hear his language: “I say the truth in Christ, I lie

not, my conscience also bearing me witness in the Holy Ghost, that I

have great heaviness and continual sorrow in my heart, for I could wish

that myself were accursed from Christ [was willing to be appointed

by Christ to suffering and death, if by that means he could save his

countrymen.—_Barnes_], for my brethren and kinsmen according to the

flesh.” _Romans_ ix. 1-3. Did religion drive away patriotism from the

hearts of Jeremiah, Daniel, and Nehemiah? No; instead of that, it made

them patriots in the highest sense of the term.

As a lover of my country, I cannot but be grieved to see the Gaelic dying

away in many parts. In several districts where, thirty or forty years

ago, the great body of the people remained after the English service, now

the great body of the people retire. In those districts where Buchanan’s,

Grant’s, and M’Gregor’s poems were read and sung, now the great body of

the people cannot read a word of them; and as for their beautiful airs,

they have lost them almost entirely. This has arisen, no doubt, from the

youth not having been taught to read it in their schools; and the reason

of that again is, that it is generally considered as a barrier in the way

of their education. Parents wish to make scholars of their children, and

they think the best way to do so is by renouncing the Gaelic altogether.

This, I have no hesitation in saying, is a false, and quite an erroneous

view of the subject. The Germans, the greatest scholars in the world—I

have been told that the first language which many of them study is the

Gaelic; and I can tell those parents who wish to make scholars of their

children, by all means to give them a good English education, but never,

never lay aside the Gaelic, but have them well grounded in it. Where is

the man that ever attempted to acquire the knowledge of Latin, Greek,

or Hebrew, that did not feel how greatly he was aided in doing so by a

knowledge of it? Were one to see two boys at school together enjoying

equal advantages, the one having the Gaelic and the other not, he would

generally see the Highlander actually rising above his fellow; and I

believe that were Highlanders to enjoy equal advantages with others,

they would be found generally rising above their fellows at college.

Were there two brothers of equal talents—the one to neglect the Gaelic

entirely, and to commence with the English, then Latin, Greek, and

Hebrew; and the other with greater patience, while engaged with the

English, to have himself well grounded in the Gaelic, and then, although

more tardy and apparently behind his brother, to commence with Latin,

Greek, and Hebrew, he would in the long run fairly outstrip his brother.

It has been remarked that, in the time of the Peninsular war, none in the

British army could more readily hold intercourse with the inhabitants

than the Highland regiments. The Governor of Auckland, New Zealand, is

a Highlander, and the reason why he succeeded to that honourable post

was because he was enabled to act as an interpreter between the British

and the natives. How was he so successful? His knowledge of the Gaelic

accounts for it.

Another thing that has a tendency to do away with the Gaelic is because

individuals from the low country are getting in amongst them, and as they

find the people able to converse with them, they do not put themselves

to the trouble of acquiring a knowledge of their language. I would not

wish my countrymen to act uncivilly towards such, yet I think they might

show them at least that they respect their own language; and as they have

chosen the Highlands as their place of residence, they would also choose

their language as their own. I have known many who could not speak one

word of Gaelic, and who in a short time could speak it quite well.

Another thing that has a tendency to do away with the Gaelic, is, that

many Highland ministers marry wives who cannot speak one word of Gaelic.

Their children, especially their daughters, follow the mother, and not

one word of Gaelic is spoken in the family, nothing but genteel pure

English. So that the man, however hearty a Highlander he might have been,

is fairly vanquished in his own house. He loses heart in the Gaelic; not

accustomed to speak it in his family, he loses his relish to preach in

it. He gets careless about it in his sermons, in the school, and in the

whole parish; and perhaps whispers in the ears of some that it is in

vain attempting to keep it up, and that it is as well that it should die

a natural death. The daughters are no doubt taught music and drawing,

and, of course, French, but not one word of Gaelic, which is considered

too vulgar for young Misses. And these the daughters of a Highland

clergyman—a Gaelic preaching minister! Tell it not in London, publish it

not in the streets of Paris, lest the daughters of the former rejoice,

lest the daughters of the latter triumph. I think that a minister’s

wife should be humble, and so condescending as that when she enters the

manse she should provide herself with Munro’s Grammar and M’Alpine’s

Dictionary, and with the aid of her husband and female servants, to

master the Gaelic, which would be more to her credit than—while their

union lasted—to be in the habit of leaving her pew, and retiring with

the genteel, the fashionable, and the gay, when her husband was about to

commence the Gaelic service; proving to a demonstration that she had no

great regard either for himself or for the truths which he preached.

It has a tendency likewise to do away with the Gaelic that the genteel,

the polite, and the fashionable do not speak it. Genteel! That man does

not deserve the name of a Highland gentleman who does not speak, not

only the English, but the Gaelic properly. It is true that there are

many Highland proprietors going about through the country dressed in the

Highland garb, who cannot speak one sentence properly in the Gaelic. Were

I to meet any such I think I would be disposed to give them the following

salutation:—“I am glad, sir, to see you in that dress, but how dare you

wear that kilt without speaking the Gaelic?” Were these gentlemen to

know the commanding influence which the Gaelic would give them in the

affection and esteem of the people, and how their very names would be

cherished by them, not only during their life-time, but embalmed after

their death, they would consider it a perquisite to a Highland proprietor

to speak the Gaelic. If there is an individual on earth that I would be

disposed to envy, he is a Highland proprietor who speaks the Gaelic, who

appears among his tenants,—not as the haughty lord, not as the sectarian

bigot, not as the foreigner, not in his representative, the factor—but in

his precious self; as the warm-hearted, the noble, the homely Highland

gentleman. The command of such a man would move the whole country,

because he who gave it had a place in the affections of the inhabitants.

His threatenings would have a greater influence in keeping down roguery

than all the police in the world, and his frown would be more dreaded

than transportation for life. There was a very touching account given in

the _Perthshire Advertiser_ of the late John Stewart Menzies, Esq., of

Chestill, not more touching than true. I know the thrill of delight it

spread, not only amongst his own tenants, but over the whole country,

when it was known that he would not allow his servants to speak anything

to his children but the Gaelic. I remember seeing him upwards of twenty

years ago, when in the prime of manhood—the day that the Queen arrived

at Taymouth Castle. The impression is still fresh upon my mind,—the

noble appearance of the man dressed in the Highland garb, the sonorous

sound of his voice as he addressed the Highlanders in Gaelic, requesting

them to give three hearty cheers, so loud as to be heard at Benmore (a

mountain upwards of twenty miles distant.) He gave a similar address in

English, but it made no impression on me compared with the Gaelic. There

was a majestic tone that accompanied the Gaelic which the English could

not imitate. The Breadalbane Gaelic is the most appropriate that could

be used from the lips of commanding officers of any in the Highlands. I

could easily conceive what a powerful effect an address from a Chieftain

would have over his clan in ancient times.

I know that we have been accustomed to look upon ourselves as a sociable

and warm-hearted race, and to look upon our neighbours as cold-hearted.

Now, the Lowland Scotch are anything but cold-hearted; they are also

warm-hearted; but compared with us they are cold—at least we think them

so. We cannot be called a cruel people; no doubt there are such among

us—it is not our characteristic. We cannot be called proud or haughty.

There is a good deal of that amongst us, but it is generally confined

to a certain class, and more in the west than in the east—it is not our

characteristic. We cannot be called a deceitful race; there is certainly

too much of that amongst us, but it is not universal, it is confined to

certain individuals. I have known some long-headed fellows amongst us,

as perfectly up to the art of deception as any I have ever seen—still it

is not our characteristic. Revenge cannot be called the characteristic

of Highlanders. Revengeful certainly they are, and perhaps as much so as

any in Britain, so that I cannot, I dare not say that revenge may not

be characteristic of some of them—still it is not their characteristic.

This then is the characteristic of our race—_a warm-hearted Highlander_.

I know, without fear of contradiction, that this will find a response in

every mind that knows them properly. It is also characteristic of the

native Irish. If Robert Burns saw that nasty thing amongst us which he

called “Hieland pride,” he saw something else that caught his attention,

namely, “a Hieland Welcome;” and what can that be but the welcome that

the warm-hearted give to their friends. I know a young lad who was in a

certain glen for a week in search of sheep who had wandered. He was in

many a house, but in none of them did they ask him “Had he dined?” No

such questions were put, but in every house they put meat on the table,

and urged him with a heartiness peculiar to themselves, to partake of it.

Now, I ask, where in Scotland or in England would a man meet with such

warm-hearted hospitality. The same lad was in a house at another time,

where the wife was a Baptist, who asked him, “Have you breakfasted?” He

reasoned with himself—If I say “No,” it will be the same as asking my

breakfast, so he said “Yes.” The consequence was that he was that day

in the hills without breakfast, well chastised for telling a falsehood.

But was the good woman to be justified after all; ought she not to have

entered more into the feelings of bashful youth. I know two ministers

who were in a certain glen preaching the Gospel together. The one a

Highlander, the other asked him two or three times, “Where shall we rest

all night?” The other had no anxiety on the subject, knowing that the

difficulty would be how to refuse invitations, answered, “Do you see that

slated house on the other side of the river?” “Yes,” he replied. “Well, I

do not know who is there, but if we get no other place we’ll go there.”

Now, a warm heart is one of the most agreeable features of human nature.

Whatever a man may have, if this be awanting in him, he is destitute of

that which would render him an object of affection. A man may be wise,

shrewd, clever, intelligent, patient, and even sincere; but if he has

not a warm heart, he is destitute of the brightest ornament that can

adorn his nature. Now, I ask, what is it that gives us this feature

in our character? Is it because we entered into the world with kinder

dispositions than others? I have no idea of that. I believe it is our

Gaelic that has done it. Whether it was our warm hearts that gave us

the Gaelic, or the Gaelic that gave us the warm hearts, is a difficult

question. The influence, I believe, has been mutual. And I am certain,

if there is a language upon earth that might be called the language of

a warm-hearted people, it is the Gaelic. So that, as a race, we have

received our shape from the mould into which we have been cast, by the

lips of our fond mothers pouring the eloquence of their affectionate

souls into our tender minds. I have known mothers in the Highlands,

who could speak the English as well as any in Edinburgh who, when

their children, being hurt, came crying to them, would fling away their

grammatical English as quite unsuited for the occasion, and begin to

address them in the endearing epithets of the Gaelic, which alone could

express their feelings.

Let any person compare the endearing epithets in the Gaelic with those

in the English, and even in the broad Scotch, which is far in advance of

the English in that respect, and he cannot but see how far short they

come. They are few in the English—“love,” “my love;” “dear,” “my dear;”

“darling,” “my darling.” They are not only few, but they are entirely

without melody. There is no melody in “love:” the lips are closed in

pronouncing it, and entirely exclude melody. “Dear” is equally destitute

of melody: it ends with the driest, and the letter that has the least

melody in the whole alphabet. “Darling” is not so bad, but comparatively

has no melody. Now, to say that melody has no effect upon the human mind

the whole world would contradict. It is a principle of nature’s teaching,

that melody affects the human mind. The English language is artificial,

and not the language of nature, and consequently is entirely without

melody.

Let these endearing epithets be put into the lips of that enchantress,

the Scotchwoman, who sets to music almost everything that passes through

her fingers:—“Love,” “lovie,” “my lovie;” “dear,” “dearie,” “my dearie;”

“my wee darling,” “my darling petty,” “my darling Johnnie;” “my wee

lammie,” “my darling lammie;” “my sweetie,” “my sweet babie.” There is

melody for you that would charm the very adders. Ah! but it is vulgar.

“They are sour, they are sour,” said the fox, when he could not reach

at the grapes. It is vulgar when the pride of a refined style of pure

English prevents many from using it. If there is vulgarity in it, it is

such as the English language cannot produce—not indeed, on account of its

vulgarity, but on account of its true refinement.

Let us turn now to the endearing epithets in the Gaelic, and we shall

find them towering as high above the English and the broad Scotch as our

Highland mountains tower high above theirs. _Gradh_, _a ghraidh_ (love,

my love), the _dh_ almost silent; _a ghraidh_ is equally strong with “my

love,” and full of melody; _gaol_, _a ghaoil_ (love, my love, or dear,

my dear). “_Ghaoil, a ghaoil, do na fearaibh_,” (M’Lachlan), the most

endearing expression which could come from the lips of man, which the

English cannot imitate, and which it is impossible properly to translate.

The nearest approach that can be made to it—“Thou dearest, or most

beloved, or most loving of men.” How touching _Mo ghaolan_, _mo ghaolag_,

the former the diminutive masculine, the latter the diminutive feminine,

the _an_ being the sign of the one and the _ag_ the sign of the other,

and being the same as in broad Scotch affectionate. _Cheist_, _a cheist_,

_mo cheist_, _mo cheistean_, _mo cheisteag_ (the question, thou art the

question, thou art my question, thou art my wee question, boy or girl).

What is the question with the fond mother? What shall I do with my

child? How shall I comfort him? How shall I make him happy? _Eudail_, _m’

eudail_, _m’ eudail bheag_—(thou art property, thou art my property, thou

art my wee property). _Eudail_ literally means cattle or property of any

kind. _Run_ literally means intention, secret, disposition, inclination,

regard; but when used as an endearing epithet, it is the strongest in any

language, and means an object where all the desires and affections of the

soul meet as in a focus, an object on which they are fixed.

O’n bha Iosa, mo rùn,

Greis ’n a luidh anns an ùir,

Rinn e’n leaba so cùbhraidh dhomhs.—M’GREGOR.

This is the epitaph which I wish to place on my grave-stone, which cannot

properly be translated.

Because Jesus, my run,

Was asleep in the uir (dust),

This bed he perfumed to me.

How often such expressions as the following are heard from the lips of

mothers, and are still more powerful when they come from the lips of a

father:—_O! a ruin, gabh mo chomhairle_ (O my child, take my advice); _Mo

runan beag_ (My wee dear boy); _Mo runag bheag_ (My wee dear girl); and,

used as an adjective, _Runach, mo bhalachan runach_ (My wee loving boy);

_Mo chaileag runach_ (My wee loving girl). We have another word, which

is the sweetest in the language and full of melody, _Luaidh_, the _dh_

being almost silent. It literally means “mention,” “to make mention;” but

when used as a noun it means “a beloved person,” “an object of praise,”

“an object on which to expatiate or to talk about by way of praise.” How

powerful from the lips of parents or friends—_Mo luaidh, a luaidh nan

gillean_ (thou dearest of lads); _a luaidh nan nighean_ (thou dearest of

girls).

It adds greatly to the force of these epithets when used along with _mo

chridhe_ (my heart), as _a ghraidh_, _a ghaoil_, _a cheist_, _eudail_,

_a run_, _a luaidh mo chridhe_. Any one of these epithets used along

with _mo chridhe_, from the lips of an affectionate mother, is as much

calculated to soften the heart, and to bring tears from the eyes, as any

sounds that can come from the lips of a human being. And equally strong,

if not more so, _a laoidh mo chridhe_ (thou calf of my heart). Do not

laugh at us, ye Lowland mothers—ye have your ain “wee lammies,” and we

have our ain “wee calfies,” and recollect that our calfies are bonnier

than yours. And, besides, I suppose it is seldom you give milk to the

ewe’s lammies; that is not, however, the case with our mammies—they

frequently give milk to the cow’s calfies, and hence it cannot but occur

to them that each has a calfie of her own to give milk to. The proper

pronunciation of this word is impossible for an Englishman to come to,

and might be called the shibboleth. There is no sound in the Gaelic that

has more of that melody that subdues and softens. The tongue has scarcely

anything to do but merely to touch the upper teeth in pronouncing the

_l_, and then to withdraw, and, remaining passive, the sound is made by

the gullet, and is as if it proceeded from the heart.

For “my sweet lammie,” we have _m’uanan_, _m’uanag mhilis_, masculine and

feminine. For “darling,” “my darling,” we have _chiall_, _mo chiallan_,

_mo chiallag_—both in the diminutive masculine and feminine; and let

it be borne in mind that the diminutive in the Gaelic is expressive

of affection like the broad Scotch. For “kind,” “kindness,” we have

_caoimhneas_, _caoimhneil_, full of melody. But we have also _caoin_

(kind), which is taken from the verb _caoineadh_ (weeping). We know that

weeping is generally expressive of kindness. It is very extraordinary

that _guil_ (to weep), is taken from _guth shuil_ (the voice of the

eyes). There is another word still, and equally melting, and more

soothing to the feelings, _caomh_ (kind), _caomhail_ (kindly), _caomhach_

(a kind person), _caomhan_, _caomhag_, masculine and feminine diminutive.

_Mo dhuine caomh_ (my kind man), the most endearing expression that

can come from the lips of a woman to her husband. I have never had

the pleasure of listening to the endearing epithets expressive of the

maternal feelings of a Northumberland, a Yorkshire, or an Essex mother;

but I am pretty certain that nature has supplied them with something more

expressive of their feelings than the English language can do.

Ye Lowland Scotch, look at our language! Many surly critics amongst

you have hitherto been listening to it with the ear, and looking at it

with the scowling eye of contempt. Look at it again—look at it aright,

and that contempt will give place to admiration! Ye refined, ye learned

Englishmen, enter this our vale of Athol through the Highland mouth’s

paradise, Dunkeld; not with railway speed, but at your leisure. Let your

ears be charmed with the melody of our groves, and let your cold hearts

be warmed with the comforts of our Highland homes.

Now, my countrymen, look at your own language. Have you any cause to be

ashamed of it? Have you not cause rather to be proud of it, and even to

bless God for giving you such a language? Would you wish to renounce

that language, so expressive of the kindest feelings of the heart, and

which has made us what we are—a warm-hearted, sociable race? Would you

wish to renounce it, and to receive in its place the language taught

in your schools? Should you ever do so, let me tell you that you will

renounce your warm hearts along with it—both shall be buried in the same

grave together, and you will make but a very poor exchange; as poor,

as if you passed from sunny France to Greenland, the land of snow and

frost. The language taught in your schools is for the head, but not

for the heart—for the understanding, not for the soul; yes, for the

mental faculties, not for the affections. And as such study it; you will

never be great scholars without a knowledge of it; it is essential to

obtaining the knowledge of the different branches of education. But let

it never be the language of your firesides, of your parlours, of your

social gatherings. The language taught in your schools is the language

of scholars, of learned men (these dry mortals); and may be called the

language of art, or an artificial language. But your language is the

language of nature, of affectionate parents, kind-hearted companions, of

your countrymen; and while speaking it you act as natural a part as the

sheep in bleating.

Men’s great effort in the present time is to do away, not only with

the Highland Gaelic, but also with the Provincial dialects in Scotland

and in England; and to substitute in their place pure English. All are

drilled with the same grammars—regulated by the same vocabularies,

without one word but proper English; and every word to be pronounced

with the same accuracy. This is what they aim at, and rejoice in their

success; and are apt to pity those poor creatures that are not willing to

be ruled by them. Well, should they be successful and reach the summit

of their ambition, to which they no doubt look forward with pleasure;

when they shall get every man, woman, and child, from John o’ Groat’s

to Land’s End, under the sway of pure English, and, standing on the

highest pinnacle of the pyramid which they have reared, what shall they

behold? One universal, uniform level. No rising ground, no elevated

spots, no sloping eminences, no ranges of mountains to relieve the

mind and please the eye. Should they be successful, instead of being a

source of rejoicing to them, they would have a greater cause to weep

over the havoc they have made in the beautiful variety of nature; more

resembling the work of locusts than of rational men. Man’s great effort

is uniformity, perfect uniformity. God’s method is variety. Which the

most glorious—man’s uniformity or God’s variety? The former like the work

of a man, the latter like the work of a God. The former would sicken my

soul, the latter would put me in ecstasy. And the same effort is made

by all the different denominations of Christians. Uniformity of creed

and of worship is their great aim and wish; and the more successful they

are, the more they are pleased with themselves. But by persevering in the

course they are taking, never, never shall they reach millennial glory.

Before they shall reach that, they must not only give over their present

attempt, but retrace their steps, and rest satisfied with God’s method

of a glorious variety. In this way, and in this way alone, shall God’s

people be properly united, and enjoy one another.

Who is not delighted with the different varieties of Gaelic spoken in the

Highlands? Is it not much more agreeable than were the whole under the

sway of our standard Gaelic. The same words used, the same pronunciation,

the same tones everywhere; which would make the whole Highlands, as

regards the Gaelic, a perfect level. Whereas, in its present state, there

is a variety of scenery to relieve the mind—towering mountains here and

there.

There Ben Nevis lifting its head above the rest, as if bidding defiance

to the whole for having the best Gaelic. That was the native place

of M’Lachlan, one of the best Gaelic scholars that ever lived, and a

first-rate poet too. The Fort-William people may ascend the top of Ben

Nevis with the elegy that he composed to Professor Beattie, Aberdeen,

and defy, not only the English, but even the broad Scotch to produce its

equal. The air of that piece is one of the most plaintive that ever I

have listened to, being the air of that old song called “The Massacre of

Glencoe.”

Ben Cruachan, again, at the other end of that range of magnificent

mountains, representing the mainland of Argyleshire. And although it may

not vie with the other in point of height, it may surpass it in point of

rich pasture, and be almost its equal in point of an extensive survey

from its summit.

Ben Lawers represents the Breadalbane Gaelic, _a’ chainnt shocrach,

choir_. Some consider it too drawling; yet I am delighted with it, being

the best suited and the most appropriate that could come from the lips

of a Breadalbanite. They are the best people for being heard in the

distance that I know. A person would be almost led to think they acquired

that habit by their forefathers having been accustomed to talk with one

another across Loch Tay.

_Si-chailinn_, again, representing the Glenlyon, the Strathtummel,

and the Rannoch Gaelic, which I believe is a corruption of “_Ciche

chailinn_.” Our Lowland neighbours have retained the sense, “The Maiden’s

pap.” Rannoch has perhaps the best Gaelic in Perthshire.

_Benaglo_ represents the Blair Athol and the Strathardle Gaelic. May a

race ever surround it that will understand

Beinn a ghlodh nan eag,

Beinn a bheag ’us airgead mheann,

Beinn a bhuirich ’us damh na croic ann,

’S allt nead ’n coin ri ceann.

_Beinn a bhrachdaidh_ represents the Athol Gaelic, rich in pasture, noble

in appearance; but let it take care of a colony forming at its base, that

they will not undermine it and blow it up. Pitlochrie is extending its

cottages, filled with foreigners. May it ever be a source of protection

to the Atholites from the cold northern blasts of the language taught in

their schools.

_Ghlaismhaol_, on whose summit the three counties of Perth, Forfar, and

Aberdeen meet, we may almost score out of our list, as it has almost

deserted us.

_Benmacdui_, representing the Badenoch and the Braemar Gaelic; but let it

take care that it will not be in the descending scale.

_Beinn Bhiogair_, in Islay, raises its head as high as it can,

representing the Islay Gaelic, which is certainly good. The females

in Islay, with the exception of those in North Uist, are the sweetest

speakers of Gaelic that I know. Islay is the native place of M’Alpine,

the author of the pronouncing dictionary, which is very good, only there

are a few words with the Islay pronunciation which do not suit other

places.

_’Bheinnmhor_, in Mull, raises its head high, and so it may, for its

Gaelic is excellent. Its inhabitants speak it generally with great

correctness and fluency. But I am not sure if it can look down upon all

its neighbours. There is an island beyond it, namely, Tiree, which,

though it has no large mountains like those in Mull to boast of, still

the few it has are beautiful, and green to the top, whose inhabitants are

amongst the prettiest and the most fluent speakers in the Highlands. They

have no tone whatever like many others, and it is seldom they commit a

grammatical blunder; their very peculiarities are pretty; a person would

be almost led to think that they are born grammarians. A boy six or eight

years of age might teach grammar to one-third of the Highland population.

Their only fault is having too many English words in their vocabulary.

As this is not a fault peculiar to the Tiree people, I would caution

Highlanders against the practice. If they can find a Gaelic word to suit

the purpose, why use an English word? I have known Highlanders that had

dogs, and that disdained to call them by an English name, or to speak one

word to them in English, and who pitied those poor fellows that thought

their dogs could not be taught to answer in Gaelic.

_Chuillinn Sgiathanach_, the chief mountain in Skye, raising its head

aloft as if saying, “We have the best Gaelic in the Highlands.” Certainly

they have good Gaelic, and they speak it in a way peculiar to themselves,

which is delightful to listen to, but still no one but a simpleton would

attempt to imitate them.

_Hough mor_, South Uist (_Hough_ means mountain), raises its head as if

determined not to be behind the rest; and so it may, for it is second

to no other place in the Highlands. As for Lewes, it is like a kingdom

by itself. There we have the only individual that attempted to write

the history of Scotland in Gaelic. Thanks to him for his effort. May

he not be disappointed in his expectation. Let my countrymen show that

they appreciate his labours, by putting themselves in possession of his

work. Should he publish a second edition, the names of places, I think,

would be better as they are in English, or, if translated, to be put in

the margin. As there is a good deal of provincialism in the Gaelic of

Lewes, I think, in writing, it would be better if possible to follow our

standard of Gaelic.

As I have never been in Sutherlandshire, nor on the mainland of Ross and

Inverness-shires, I am not prepared to speak from personal knowledge of

the various shades of difference there, resembling their chief mountains;

but I know there are differences. Let each class not be ashamed of

their own peculiarity. It is the language of their nature, and they act

according to their nature when they speak it. For a Ross-shire man to

attempt to imitate an Argyleshire man would make him ridiculous, and

for the latter to attempt to imitate the former would make him equally

so. I have known men who, when they sold their stirks, spoke their own

language, but when engaged in prayer to God, spoke in the language and

tones of Ross-shire. Are they so stupid as not to know that it is not to

the tones of the voice that God will listen, but to the earnest pleadings

of believing hearts? There are several districts in the Highlands where

the Gaelic has sadly degenerated; their best plan would be to get

teachers from those parts where it is not so.

The great object, then, at present is not only to do away with our Gaelic

in all its beautiful variety, but to do away with the broad Scotch in all

its beautiful variety likewise, and to establish upon their ruins pure

English. Now, I have not one word to say against the English. I admire it

as the best that could be used for our halls of learning, for discussing

any public question, and for handling any intricate subject. But I

must declare that it has a baneful effect on society. It is the worst

language that could be used for parents, children, brothers, sisters,

companions, and for the social gathering. Being an artificial language,

it makes society so too. It has a tendency to puff them up with pride.

Instead of making them pliable, it makes them stiff; distant and reserved

instead of being homely; unnatural instead of natural; unsociable

instead of sociable; and instead of making them easy, imposes its own

yoke of ceremonial bondage upon its votaries; and I have no hesitation

in affirming, without fear of contradiction, that pure English, instead

of regenerating society, has the contrary effect. It is probable that I

may be sneered at for so affirming, but it will remain a fact when the

sneering is over, and will yet be acknowledged when I am dead and laid

in the grave. Let any person seriously consider the fearful havoc it has

made, not only in the Highlands, but also in our large cities. It has

divided society into two—the refined and the vulgar; the genteel and

the homely; the upper and the lower class; the select and the common.

What has it made of the most of our Highland proprietors? Are they what

they used to be, the men of the people, standing on a common level with

them in speaking their native Gaelic? No, they are now as if they were

a race of foreigners amongst them, high up above their heads, without

any sympathy with them, disdaining to speak one word to them but in

pure English. It has likewise a baneful effect on the middle class of

society, those who aspire after it, who put themselves amongst “the

would-be genteel,” who in the pride of their hearts, although they can

speak Gaelic, deny that they can, and become ashamed of it at home and

abroad. The consequence is, that when the English sermon is over, they

must retire with the genteel and the fashionable, and disdain to remain

amongst a company of vulgar Highlanders, listening to a vulgar discourse

in Gaelic. To what shall I compare these “would-be gentlemen and ladies?”

Shall I compare them to the vain peacock showing his beautiful tail, or

to the ass showing its long ears? I think I will compare them to both.

There they are retiring as if saying, “See what beautiful tails we have

got.” “O yes, yes,” might those within say to them, “we see them, we see

them, but we see your long ears likewise.”

Were there a discourse in broad Scotch delivered in the Lowlands after

the superfine English, depend upon it your fine ladies and gentlemen

would retire all in a band before their ears would be horrified by its

sweet melody, and it would be a first-rate excuse to pretend that they

had lost their broad Scotch.

“Scots wha hae wi’ Wallace bled.”

You are in danger also, not from the chains and slavery of proud Edward’s

power, but from another quarter you never suspect, namely, the _Dominie’s

tawse_. Take care that he’ll not rob you of your wifies, weans; your

Johnnies, Tammies, Willies; your Jessies, Katies, and Betsies; yes, your

bonnie lammies, and from many other wee bits o’ things which you hae

tingling about your hearths, and around your affections, which make you

so sociable and happy, and moreover gives you such unparalleled tongues

for melody and music. Again, as your friendly neighbour, I say take care.

I am convinced, that were the broad Scotch mixed with an English

vocabulary, and pronounced as it is generally by educated Scotsmen,

we would have a language for all the purposes of life, far surpassing

the pure English, and which, instead of it being our envy, ours would

actually be the envy of Englishmen. Such a language would not only give

us clear heads, but also warm hearts; would not only be the best for the

higher departments of literature, but the best for our homes, as husbands

and wives, parents and children, brothers and sisters; for friends;

and in the social circle; and put us in possession of lyric poetry,

such as the English language has not, and never can produce. It is most

extraordinary that intelligent well educated Scotsmen never attempt to

speak their own language but when they wish to be humorous. Now, that

really implies that they see something pretty in it after all, but that

what is fashionable and customary amongst educated men prevents them from

using it but for such a purpose. But I think that the pretty thing should

not be altogether laid aside, but freely used, not merely for making the

social circle smile, but also for warming their hearts, and making each

feel that he is quite at home—in an honest, homely, cheerful Scotsman’s

home.

How highly would I esteem that learned professor who, after delivering

his lecture to the students in pure English, would no sooner leave his

professional chair, and meet his friend, than he would salute him, not

as the learned professor, but as the homely Scotsman;—that when he would

enter his own dwelling and sit at the head of his family, he would appear

there in the same garb, and would set an example before his children, not

so much for correct speaking as for affability, kindness, and homeliness

of manner;—who, when he would appear in the social circle, would be

its life and soul—not indeed as the learned professor, but as the man

of feeling, of intelligence, and of sociality. Is it not a known fact

that great learning in a sermon actually destroys its effect, and that

great scholarship in a man eclipses the affectionate friend, the social

companion. A man brimful of learning we may admire but we cannot love.

Now, such is the English, a learned language. The Scholar is seen almost

in every sentence. I may admire it, and in doing so I feel that it puffs

me up, but love it I cannot. It is not like the Gaelic and the broad

Scotch—the language of nature—but the language of art. In the Gaelic I

see my own image reflected, but in the English the image of the scholar.

As the Gaelic reflects the image of the Highlanders, and the broad Scotch

that of the Lowlanders, I cannot but love them. I may admire the works of

art, but love them I cannot; but the works of nature I not only admire,

but actually love them also, and I cannot but do so.

The English language is not only to a great extent foreign to the Scotch

people, but it is almost equally so to the great body of the people of

England; and is it not extraordinary, that before men are considered

qualified for preaching the gospel to the native inhabitants, they must

do so in a language which they do not speak, and in a style of elocution

which is not natural to them. An Englishman’s elocution is the most

unlikely for moving a Scotchman, and far less a Highlander. I once

attended an elocution class, whether the better of it or not I cannot

say; but one day in the Highlands I opened the door and saw a woman

within twenty yards, beyond a dyke—the upper part of the body only seen,

her hair dishevelled, her hand raised, her fist shut, and scolding at

a fearful rate. I heard her tones, caught her expressions, noticed the

eloquence with which she spoke, and returned into the house, saying to

myself—“It was quite needless for me to have attended Mr Hartley’s class,

when elocution is to be found so near, and that of the right kind, the

elocution of nature.”

Is it not a fact that some of the Methodists are sneered at by the Press

for attempting to speak to the people in their provincialism. Go on,

ye lively Methodists; never heed their sneers. You are doing the very

thing which the Holy Ghost enabled the Apostles to do—to speak unto men

in their own tongues. I question if the present style of preaching the

Gospel will ever gain the hearts of the Scotch people to God. And I would

not be surprised although God would show their folly to those who attempt

to do so by raising up Evangelists—men endowed with a good fund of common

sense and natural talent—men fired with zeal for the glory of God—moved

on with warm hearts and compassionate souls, who will preach the Gospel

to them in that language which is a part of their nature and the best

medium for getting at their hearts. We know that conversion is the work

of God, but when he deals with men he uses appropriate means. He does not

lay aside the natural laws of their nature, but acts in accordance with

them. When He unlocks the door of the heart He uses a key fitted for the

purpose; and is it possible that a pure English style can be the proper

key for unlocking the heart of that man who has been accustomed all his

life long to speak broad Scotch. Had the Gospel ever such an effect as

when it was preached in the native language of the country? There is

not only an orthodox creed, but there must also be an orthodox language

and even an orthodox elocution. It is to be feared that men with their

orthodoxy will allow poor sinners to go to hell.

The orthodox creed, language, elocution, and even melodies, are all

artificial—the handiwork of that being man, who would be as gods, and

which are impossible to admire without being puffed up with a vain

conceit of his great powers. O! how different the effects in admiring

the handiwork of the Great Supreme as they are seen in nature—in birds,

beasts, fish, flowers, mountains, and dales, the native languages and

melodies of our races. The chattings of Highlanders and Lowlanders to one

another is as much the language of nature as the lowing of cattle, the

bleating of sheep, and the chirping of birds. And our native melodies are

as much the melodies of nature as the singing of larks and nightingales.

But proud man must do away with them by introducing his own artificial

language and melodies, on which he puts the stamp of orthodoxy.

The pure English has not only committed a great havoc amongst us,

both in the Highlands and Lowlands, but there is also an Englified

style accompanying it in many places which is disgusting. Were there

an English lady to settle in one of our Highland towns she would soon

be surrounded by a goodly number of mimicking parrots. Cockneyism in

Cockneydom does very well; I would almost dance with delight to listen

to it there; but Cockneyism from the lips of a Scotchman, and far more

from a Highlander, I abominate. I have been quite ashamed of some of my

own countrymen, who, when they go South, are not satisfied with merely

imitating Scotchmen, but they must become regular Cockneys. Ah! the

pride of their hearts is contemptible. I would say to a Scotchman—if you

wish to show yourself a man, show yourself a Scotchman; and I would say

the same to a Highlander—if you also wish to show yourself a man, show

yourself a Highlander. Is an Englishman alone to have the privilege and

the honour of showing himself a man? Is he and his artificial English

to be exalted as a god in every part of the United Kingdom? Must every

knee bow and every tongue confess to him? I declare, in the name of my

countrymen, that we shall not worship at his shrine; we shall not fall

down and worship the golden image which he has set up. As a race, we and

our language have hitherto been unjustly and contemptuously treated.

But as we have in times past made others feel that we were alive, we

shall not only make Scotland, but England also, feel that as a race we

are still alive and have a language of our own. So that, from this time

henceforward, should one Highlander show his peacock-tail to another by

addressing him in any other language but his native Gaelic—considering

it more genteel—let him be told at once without any ceremony, _Tha mi

ga fhaicinn, tha mi ga fhaicinn, ach ata mi faicinn cluasan fad na

h-asail mar an ceudna_; and in like manner, should a Scotchman show his

peacock-tail to another by addressing him in any language but that of his

native country, let him also be told at once, “I see it, I see it, but I

see your long ears also.”

There was an individual at one time called “the Flower o’ Dumblane.”

I wonder if there was one in the present time that might be called

the Flower of Glasgow, what like would she be. I suppose she would

be good-looking, a handsome body, and good features; I don’t say

either pretty or beautiful, but good; her expression sweet, amiable,

intelligent; her manner easy, graceful, natural; nothing awkward, nothing

artificial, but the spontaneous outflow of a kind heart, good taste,

and an enlightened mind. But how would the Flower be dressed? Of course

many would answer—quite in the fashion. I am not very sure about that;

I think quite in the fashion would disfigure the Flower. How then? Just

in such a manner as that no person would notice the dress at all, but

have the attention fixed upon the Flower, and that nothing could be said

about it but that it was befitting. But the Flower of Glasgow would not

require to be dumb, she must speak occasionally, but in doing so would

not put herself in the front rank of speakers. She would, however, be an

acute observer of what was said and done, and should anything deserve a

laugh, she would of course give a hearty one to show her white teeth and

her kind nature. When, however, any remark was made, or any question put

to her, demanding her saying something, she would of course speak out.

Bearing in mind that she is a native of Glasgow, that her mother was

that before her, a truly Scotch woman, who spoke the broad Scotch, but

considerably refined by her intelligence and good taste. Now, what would

be her style of speaking? Many would answer, no doubt, “In first-rate

English style.” I declare that that again would destroy the beauty of

your flower. There must be nothing artificial in a flower. The moment art

lays its hand upon it, or even touches it, its beauty fades. No doubt

there are many flowers in Glasgow, but many of them are artificial, and

differ as much from the real flower as the flowers in their shop windows

differ from those in the West End Park. There are many Scotch parents

who send their daughters to English boarding-schools to be as perfectly

Englified there as possible, but it is the same as if they put their

flowers into a hot-house in the month of July. A flower will never show

its beauty but in connection with its parent stem; remove it from that

and it fades.

In order that a man may be a good member of society, he must be affable

and agreeable in his manner; but he can neither be the one nor the other

unless he is homely. And how can that man be homely who assumes an

Englified style of speaking foreign to his nature. I am aware that in

certain circles to say that a man is homely is nothing to his praise,

but implies that in their estimation he is awanting in something that

would make him a better member of society. He is too homely in his

dress, in his style, in his expressions—too homely in his manner as he

sits and holds his head, laughs and smiles; in short, he is too homely

in everything. But I wonder how they would improve the homely man. I

suspect the improvement would be something like the improvement that a

number of drunkards would make upon a sober man. They are intoxicated

themselves with a vain conceit of a certain standard of refinement, and

they must do their best to get him intoxicated also. In order to come

up to their standard, he must make a fop of himself—must make a fool of

himself by assuming a style of speaking not natural to him. He must sit

and hold his head in the fashionable position; if that is not its natural

position, he would require a person to sit behind him, and with a hand on

each side to keep it in the genteel position. His laughing must be all

feigned, not hearty, not natural; his smiling must be the same. In short,

in order to come up to their standard, he must make himself a regular

play-actor, a hollow hypocrite, a downright mimicking parrot. See that

female, how straight she holds her head. Is that its natural position?

Does she keep it that way at _hame_? I suspect not—there is evidently an

effort. My young woman, I am sorry for the misery you are inflicting upon

yourself. That which is generally called refined society is a society for

inflicting misery upon their dupes, and upon their race; and the females

of that society might be called sisters of cruelty, and not “sisters of

mercy.”

Were there a society formed for improving nature as seen in birds and

four-footed animals, I suppose all men would look upon such as a society

of fools. But a society formed for improving nature as seen in the human

species, is more highly thought of than any society on earth. I leave

wise men to judge if there is not more of the fool in such a society than

they are aware of. And the first attempt that has been made to improve

the human species in Scotland is to do away with their native languages,

which are the languages of their nature, and which God hath given them

to make their feelings and their thoughts known to one another, and to

impose upon them a language which is foreign to their nature and not in

accordance with the feelings of their hearts. God knows what is better

for Highlanders than they know, and their best plan is, if they would

not set themselves up in opposition to him, to aid them in obtaining

more knowledge of their own language, for certainly they will obtain

the knowledge of salvation more readily through the medium of their own

than any language they can teach them. There are various ways in which

men attempt to improve nature as seen in the human species. I would say

leave them, let them alone to be guided by their own natural instincts

under the guidance of their parents. The only improvement that ought to

be attempted is giving them spiritual instincts—to impart the knowledge

of God to them through the medium of their own language—to make them

acquainted with God’s method of saving men through Christ—bringing

them under the influence of the love of God, giving them the hope of

glory—making them to rejoice in God their Saviour, and uniting them to

Christ and to one another in love. Then there will indeed be a refined

society, with heaven’s stamp upon it—natural, beautiful, glorious: as far

above what is called refined society as the heavens are high above the

earth.

It is true that the Gaelic is not to be compared as a learned language

with the English, being very deficient in those technical terms that are

used in the various branches of education. But for ordinary purposes, the

Gaelic is not only equal but in many things surpasses the English. The

tongue of a Highlander surpasses any that I have listened to for sarcasm,

wit, and good humour. For showing the good qualities of one, or the bad

qualities of another, it is before the English. For expressing sympathy

with a fellow sufferer—for the house of prayer—for the family and the

social circle—for expressing the conjugal, the parental, the filial, the

brotherly, the friendly feelings and affections of the heart, it is far

in advance of the English. For preaching the gospel, for expatiating

on the love of God, for holding forth Jesus Christ and him crucified,

for catching and keeping the attention, for reaching and searching the

conscience, and for applying the subject to the heart, I have always

preferred it; and I am convinced that those who know it properly, and are

in the habit of using it, have the same feelings. Its very simplicity

gives it a power which the English does not possess. Who does not see

that the very simplicity of Judah’s pleading with Joseph for his brother

Benjamin gave it greater force than had it been delivered by Lord

Brougham. Many of the translations which I have seen in Gaelic are far

too literal and stiff. A literal translation will never tell on the minds

of Highlanders. The best way is to catch the ideas, and to express them

as they would do themselves.

What the Gaelic is capable of doing is clearly seen from the _Gaelic

Messenger_ and Dr. M’Leod’s Collection, also the _Pilgrim’s Progress_

with notes, and other works of John Bunyan, translated and edited by

Dr. M’Gilvray, Glasgow, which has not only come up to the original,

but in some things surpasses it. If _Good Words_ in the hands of the

son are good, good words in the hands of the father are not behind.

Any periodical more expressive, more telling, more touching, and more

entertaining than the _Gaelic Messenger_ I have never read; and the

principal reason why that periodical had not been more extensively

circulated, and why it has ceased to exist, is the great misfortune

connected with Highlanders—that the great body of them are not taught

to read the Gaelic. This misfortune is their disgrace—the disgrace

of parents—the disgrace of noblemen and gentlemen who are native

proprietors; yes, and the disgrace of ministers and schoolmasters. Let

them all awake and wipe away the disgrace from their native country. It

is with blushing shame for my country that I have to declare that never

in my younger days did I get a single lesson in the Gaelic in any school

that I attended, and I feel the ill effects of it to this day.

There is one thing, however, in which the Gaelic greatly exceeds the

English, namely, in lyric poetry. From the very constitution of the two

languages the English will not even make a near approach to it. It is

capable of a great many contractions that the English is not capable of,

_agus_ and _’us_, _’s_. All monosyllables and trisyllables ending with

_a_, or _e_, may drop the last. Such words as _saoghalta_ (worldly),

_saoghalt_, _saogh’lt_; participles of verbs, such as _riarachadh_

(satisfying), _riarach’_, or _riar’chadh_; the verb to be, _is maith_ (it

is good), _’s maith_; _bithidh_ (will, or shall be), _bi’dh_; _bithibh_

(be ye), _bi’bh_; _bi thusa_ (be thou), _bi’-sa_. But what makes the

Gaelic so superior to the English, is, not merely that it is capable of

more contractions, but as the vowels are more distinctly sounded and the

consonants less so, we are satisfied if we get the vowels to rhyme; but

that will not do in the English, the consonants must rhyme also. The

vowels in the Gaelic have only the two sounds, the short and the long,

and are pronounced as in the broad Scotch. We have several sounds which

are not in the English at all, sounds formed by the union of two and

even three vowels, which are the most melodious in the language. Union

of two vowels—_ao_, _gaol_, _saor_ (love, free); _ia_, _grian_, _srian_

(sun, bridle); _ei_, _greine_, _srein_ (the genitive of sun, bridle);

_eu_, _speur_, _neul_ (sky, cloud); _ua_, _fuachd_, _shuas_ (cold, up);

_ai_, _baigh_, _traigh_ (kindness, seashore); _io_, _fior_, _dion_ (true,

protection); _eo cleoc reota_, (a cloak frozen). The union of three

vowels, the sweetest sounds in the language—_aoi_, _aoibhneas_ (joy);

_uai_, _buaidh_ (victory). Besides these, there are many words where

_eu_ may be changed into _ia_, as _feur_, _geur_, _neul_ (grass, sharp,

cloud), _fiar_, _giar_, _nial_. The former is the standard Gaelic, but

the latter is more common in the west and north.

To translate lyric poetry from English into Gaelic is comparatively

easy, but to translate it into English is not only more difficult, but

we have many pieces which cannot be translated at all so as to rhyme.

Let any person compare our metrical version of the Psalms of David with

the English, and he cannot but see how superior it is; and even the

paraphrases, although originally composed in English, the Gaelic not only

comes up to it, but actually surpasses it in many places. In the English,

in common metre, the last syllable of the second and fourth line only

rhyme, whereas frequently in the Gaelic the last syllable of the first,

and the fourth of the second rhyme.

“C’arson a struidheas sibh ’ur maoin

Air nithibh faoin nach biadh;

’S a chailleas sibh ’ur saoth’ir gach la,

Mu ni nach sasuich miann?”

How smoothly and sweetly does that rhyme flow compared with the English.

I have seen a book called the _Highland Bards_, translated by a great

scholar, and although done as well as possible in a translation, yet

every one who knows Gaelic cannot fail to see how far short it comes of

the strength and beauty of the original. No man, however great, can do an

impossibility. I have also seen translations of Dugald Buchanan’s Poems,

and these by men who were greater scholars than himself; and on looking

at them, I saw as great a change between them and the original as if I

had seen Dugald himself when in his prime, and again at seventy, when it

would be all I could do to recognise his features, but O how changed!

Taking his poem on the day of judgment, I defy the English language to

produce its equal as a piece of lyric poetry. In the language there is

scarcely a single word coined from another language, perhaps a few from

the broad Scotch that came to be naturalized—all the language of his

native country, extraordinary for its simplicity and expressiveness. The

rhyme of that poem is smooth, it is perfect. I have attempted, or should

rather say, I have endeavoured to improve what others attempted, and the

best I could make of some of the verses I give in the following:—

My worldly thoughts, O God inspire,

And touch my lyre that it may play,

That I may put in solemn rhyme

Thy most sublime and awful day.

O! listen all ye sons of men,

This world’s last end is come to pass,

Start all ye dead to life again,

The great Amen has come at last.

The sun, great majesty of lights,

To his great brightness shall succumb,

The shining radiance of his face,

His light with haste shall overcome.

Was it enough that nature’s sun

Aghast did shun the deed to see,

Why did not the creation die

When Christ expired upon the tree?

These are equally strong, and rhyme well, but where is the melody

compared with the Gaelic, and it is most extraordinary that I cannot sing

them without feeling that I am puffed up with the language, whereas in

the Gaelic I have no such feelings. The English will never come up to the

following, sublime in their simplicity:—

Mu mheadhon oidhch’ ’nuair bhios an saogh’l,

Air aomadh thairis ann an suain;

Grad dhuisgear suas an cinne daoin,

Le glaodh na trompaid ’s airde fuaim.

Look at the rhyme how smooth and agreeable to the ear—the language how

simple and artless, the scene presented how solemn. We can scarcely

conceive of any thing more so, than the world having reclined over in

sleep’s soft repose, and then suddenly to be awakened with the trumpet’s

loudest sound.

The English language completely fails in giving a proper translation;

being an artificial language, it disfigures almost every thing it handles.

When the whole world in midnight’s lull,

In silent slumbering sleep is found,

Their rest shall quickly be disturb’d

By the last trumpet’s awful sound.

The following are sublime:—

Tha’m bogha frois muo’n cuairt d’a cheann;

Mar thuil nan gleann tha fuaim a ghuth,

Mar dhealanaich tha sealla ’shul,

A sputadh as na neulaibh tiugh.

Not a single expression but what a herd lad, who was never at school,

could use, and yet how sublime. Put it into the hands of the mistress of

arts, and see how it will appear.

The rainbow bright surrounds his head,

Like flood of glens his voice divine,

Like lightning flashes ’mid dark clouds

The astounding glances of his eyes.

There it is pretty strong, but where is the melody so agreeable to the

ear? The English will never make it rhyme without divesting it of its

sublimity.

Tha mile tairneanach ’na laimh

A chum a naimhdean sgrios a’m feirg,

’S fonna-chrith orr gu dol an greim,

Mar choin air eill ri am na seilg.

Try that again.

A thousand thunders in his hand

At his command his foes to crush,

Shivering, eager to be engaged

Like hounds restrained by the leash.

This is not so far amiss, only “crush” and “leash” as it regards the

vowels, do not rhyme. Look at the Gaelic—how simple; every word forged

and hammered on the anvil of a Highlander’s method of making his thoughts

known. Consider the sublimity of the passage. Dugald was not a classical,

but one of nature’s scholars, who had learned his lessons well, and

I am certain that in learning them he was not puffed up as they are,

but rather humbled. Thunder, one of the most awful agents conceivable.

When the thunder roars the earth keeps silence. A thunder held in the

hand—how sublime? A thousand thunders, a thousand times more so. How are

these thunders held? Like hounds restrained by the leash. Anything more

expressive could not come from the lips of man. A hound at first sight of

the game would almost choke himself at the first spring, if restrained.

Are these things so; and how perilous the condition of those who are

the enemies of the Great Judge? The air to which that poem is sung is

also most appropriate; so that in singing it, one never thinks either of

the language or the melody, any farther than that they are expressive;

but has his mind wholly occupied with the sublime, the awful, and the

beautiful imagery presented before it. I have heard that poem sung to a

crowded audience, and I have never listened to anything spoken or sung

that had a greater effect. Every eye fixed; all attention; awe, anxiety,

concern depicted on every countenance. And I can tell Ministers of the

Gospel all over the Highlands, that could they get two or three to sing

that poem properly to their congregations, that it would have a far

greater effect than most of their sermons. And I can tell them, moreover,

that that poem sung once had a more blessed effect than all my sermons

for a whole twelvemonth.

There are three poems of M’Gregors composed to suit the air of an old

song, called “_Gaoir nam ban Muileach_” (The wail of the Mull women).

There are seven lines in the stanza, and the last is repeated twice.

In singing it it resembles the regular flow of a torrent, but when it

reaches the sixth line it comes to a climax as if the torrent had become

a beautiful waterfall. Or to use another simile. The first part of it

resembles the Atlantic waves as they roll majestically to the shore,

rolling and rolling along with a good deal of monotony till at length

they reach the climax, when they break forth with a tremendous crash like

rolling thunder. Were there a few individuals who could sing it together

till they reached the sixth line, and then the whole to unite with them,

there would be such singing as I have seldom listened to.

Thaom e spiorad neo-ascaoin

Air a naoimh ’us air ’abstoil,

’S rinn iad saighdearachd ghasda,

Mine, macanta ’n gaisge;

Cha do phill iad le masladh,

Ach troimh Chriosd a thug neart dhoibh,

Chuir iad cath gus ’n do chaisg iad an namhaid.

Chuir iad cath, &c.

Perhaps some of my countrymen do not know what _neo-ascaoin_ means;

_caoin_ means kind; _ascaoin_, unkind; _neo-ascaoin_, the reverse, that

is great kindness. I will endeavour to give a translation as near as

possible.

He poured his spirit most kindly

On his saints and apostles,

Who acted most soldierly,

Meekly and lowly in heroism,

Not turning disgracefully,

But through Christ that strengthened them

They fought till they routed the enemy.

Although all the masons in the world were to go on hammering at the

English for a century, they could not make it rhyme like the Gaelic in

this verse. I have composed a considerable number of poems. I suppose,

when published together, they will form the largest collection in the

language. I attempted to translate two or three of them, but found

it impossible to do so by strictly following the rules of English

versification. I attempted to translate more, but found I could not

translate one verse to my satisfaction, and I wish that scholars would

understand this—that it is utterly impossible to give them anything like

a correct idea of our poetry, unless we are allowed to follow the Gaelic

rules of versification, and even with that licence we cannot come up to

it. I saw in a periodical a review of the lyric poetry of Wales, which

showed that it was impossible to give a proper expression of it in an

English translation. The same is equally true of the Gaelic. The strict

rules to which he is tied down who would attempt to compose English verse

prevent him from soaring like the eagle, and his productions must be

comparatively tame, and awanting in energy.

Singing has a mighty power over the human mind, which the church to a

great extent has neglected, and a power which she never wields aright

but when in a revived state. I once went into a house; but the moment I

entered, the youngsters, some of them men and women, all fled. “See,”

said the mother, (a pious woman), “how they have all gone.” “Yes,” I

said, “but we’ll soon bring them back,” and so commenced to sing a

poem, not to the tunes of Martyrdom or Oldham (these would not bring

them back), but to the tune, “Whistle o’er the lave o’t,” and they all

returned immediately.

How shrewd the remark, “Give me the songs of a nation, and I care not

who gives them laws.” It has been stated that the poems of the great

reformer, sung to the native melodies of Germany, had a greater effect in

promoting the Reformation than all his writings. I have heard melodies,

but any that come up to our native melodies, both Highland and Lowland,

I have not heard. If the songs of our country, many of them, have such a

bad effect, and the melodies so sweet and fascinating, why not regenerate

the song? By so doing the instrument would be wrested from the hands of

the enemy; the sword taken from the great Goliath to cut off his own

head, and to destroy the Philistines. In this respect we are in advance

of our neighbours; our songs to a considerable extent are regenerated

already. Dugald Buchanan’s Poems I place first, being superior to any

that has appeared yet, so far as poetry is concerned. Duncan M’Dougall,

a native of Mull, but ultimately residing in Tiree, has a considerable

number, I suppose, with the exception of Peter Grant, the largest

collection we have. His poems are good, most of them sung to the airs

most common in Tiree and Mull. Daniel Grant, a native of Strathspey,

but residing in Athol, comes next to M’Dougall in point of number, and

although he is not his superior either as a Gaelic scholar or as a poet,

he is his superior for conveying real spiritual instruction to the mind.

He has picked up some of the airs in Athol and Strathspey, and even

some from the low country. Donald Henry, I believe, a native of Arran,

has also left some very sweet poems, of which many are very fond. J.

Morrison, Harris, was an extraordinary genius. His language is superior

to Dugald Buchanan, and is not his inferior as a poet. He had more of the

language of the Highland bards that puffs up. Dugald had nothing of that,

but was powerful in his simplicity. The former resembles David clad in

Saul’s armour, the latter David with the sling and the stones. In singing

Morrison’s we cannot but think of the bard, but in singing Dugald’s

he is not thought of at all, and almost every word tells. Dr M’Donald

has left a considerable number of poems; some of them are elegies. He

was certainly the most powerful preacher in the Highlands in his time,

and anything said in his praise is superfluous, as it is all over the

Highlands. Yet it strikes me that he did not shine so much as a poet as

he did as a preacher. His poetry is certainly good, but there is nothing

extraordinary about it, as there is about his preaching. “The Christian

on the Banks of Jordan” is excellent, and very expressive; but there

are some pieces of his containing his own views of disputed points of

doctrine, with an evident intention to give a hit at those who differed

from him, which are not suitable for being sung in the praises of God.

Songs of praise should be for the whole church. No doubt he considered

those opposed to him as holding error, but they consider that he holds

error too, and how is the matter to be settled? Is it not possible to

hold the doctrine of election, and at the same time to hold that, in a

certain sense, Christ died for all men? Is it not possible to lay the

blame at the sinner’s door, where it shall be left at the last day,

without denying the necessity of Divine influence in his conversion?

I come now to my great favourite, M’Gregor. Buchanan was his superior as

one of nature’s poets, and perhaps his superior in point of style. He

did not show so much of the scholar. The scholar seen in lyric poetry,

instead of adding to it, rather detracts from it. But, notwithstanding,

M’Gregor was his superior by far as a theologian for bringing varied and

important truths before the mind. I have seen many a book, but a book of

its size which contains more important truth I have never seen. Every

truth that is important for the Christian to know is systematically

laid down; every poem is like a well-composed discourse, the subject

experimentally handled in all its bearings; and all that in language

excellent, in versification perfect, and suited to be sung to some of

the most beautiful melodies of our country. I have never quarrelled with