The Project Gutenberg EBook of A Little Book for Christmas, by Cyrus Townsend Brady

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most

other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of

the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at

www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have

to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: A Little Book for Christmas

Author: Cyrus Townsend Brady

Release Date: March 12, 2005 [EBook #15343]

[Most recently updated: July 31, 2020]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK A LITTLE BOOK FOR CHRISTMAS ***

Produced by Gene Smethers and the PG Online Distributed Proofreading Team

A Little Book for Christmas

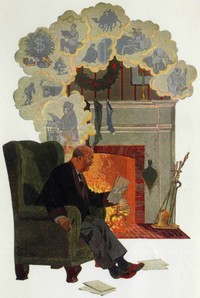

[Illustration: The author making his book, as pictured by his friend,

Will Crawford.]

Containing a Greeting, a Word of Advice, Some

Personal Adventures, a Carol, a Meditation, and Three Christmas

Stories for All Ages

By

Cyrus Townsend Brady

Author of “And Thus He Came, A Christmas

Fantasy,” “Christmas When the West Was Young,” etc., etc.

With Illustrations and Decorations by

Will Crawford

G.P. Putnam’s Sons

New York and London

The Knickerbocker Press

1917

DEDICATED

TO

MRS. LEONARD L. HILL

AND HER CHARMING COMPANIONS

OF

THE AMERICAN CRITERION SOCIETY

OF NEW YORK

BY

THEIR CHAPLAIN

[Illustration]

PREFACE

Christmas is one of the great days of obligation and observance

in the Church of which I am a Priest; but it is much more than

that, it is one of the great days of obligation and observance in

the world. Furthermore it is one of the evidences of the power of

Him Whose birth we commemorate that its observation is not

limited by conditions of race and creed. Those who fail to see in

Him what we see nevertheless see something and even by imperfect

visions are moved to joy. The world transmutes that joy into

blessing, not merely by giving of its substance but of its soul

because men perceive that it is for the soul’s good and because

they hope to receive its benefits although they well know that

giving is far better than receiving, in the very words of Him Who

gave us the greatest of all gifts—Himself.

As a Priest of the Church, as a Missionary in the Far West, as

the Rector of large and important parishes I have been brought in

touch with varied life. Christmas in all its phases is familiar

to me. The author of many books and stories as well as the

preacher of many sermons, it is natural that Christmas should

have engaged a large part of my attention. Out of the abundance

of material which I have accumulated in the course of a long

ministry and a longer life I have gathered here a sheaf of things

I have written about Christmas; personal adventures, stories

suggested by the old yet ever-new theme; meditations, words of

advice which I am old enough to be entitled to give; and last but

not least good wishes and good will. I might even call this

little volume _A Book of Good Will toward Men_. And so fit it not

only for Christmas but for all other seasons as well.

If it shall add to your joy in Christmas, dear reader, and better

still, if it shall move you to add to the joy of some one else at

Christmas-tide or in any other season, I shall be well repaid for

my efforts and incidentally you will also be repaid for your

purchase.

Cyrus Townsend Brady.

The Hemlocks, Park Hill,

Yonkers, N.Y.

1917

NOTE OF ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The author is in debt to his long-time and greatly beloved friend

the Rev. Alsop Leffingwell for the beautiful musical setting of

the little carol which this book contains.

[Illustration]

TABLE OF CONTENTS

I.—A CHRISTMAS GREETING

“_Peace on Earth, Good Will toward Men_”

II.—FROM A FAR COUNTRY

A story for grown-ups

_Being a new variation of an ancient theme_

III.—ON CHRISTMAS GIVING

_Being a word of much needed advice_

IV.—IT WAS THE SAME CHRISTMAS MORNING

A story for girls

_In which it is shown how different the same thing may be_

V.—A CHRISTMAS CAROL

_To be sung to the music accompanying it_

VI.—THE LONE SCOUT’S CHRISTMAS

A story for boys

_Wherein is set forth the courage of youth_

VII.—LOOKING INTO THE MANGER

_A Christmas meditation_

VIII.—CHRISTMAS IN THE SNOWS

_Being some personal adventures in the Far West_

IX.— CHRISTMAS WISH

_For everybody everywhere_

[Illustration]

[Illustration]

ILLUSTRATIONS

The Author Making his Book

“I sought dat Santy Claus tame down de chimney,” said the younger of

the twain.

“I am sure, Miss, that they do wish you a Merry Christmas.”

“The Stars look down”

“Thrusting his toes into the straps he struck out boldly.”

“The world bows down to a Mother and her Child—and the Mother herself

is at the feet of the Child.”

[Illustration]

A CHRISTMAS GREETING

“_Good Will Toward Men”—St. Luke 11-14._

There was a time when the spirit of Christmas was of the present.

There is a period when most of it is of the past. There shall

come a day perhaps when all of it will be of the future. The

child time, the present; the middle years, the past; old age, the

future.

Come to my mind Christmas Days of long ago. As a boy again I

enter into the spirit of the Christmas stockings hanging before

my fire. I know what the children think to-day. I recall what

they feel.

Passes childhood, and I look down the nearer years. There rise

before me remembrances of Christmas Days on storm-tossed seas,

where waves beat upon the ice-bound ship. I recall again the

bitter touch of water-warping winter, of drifts of snow, of

wind-swept plains. In the gamut of my remembrance I am once more

in the poor, mean, lonely little sanctuary out on the prairie,

with a handful of Christians, mostly women, gathered together in

the freezing, draughty building. In later years I worship in the

great cathedral church, ablaze with lights, verdant and fragrant

with the evergreen pines, echoing with joyful carols and

celestial harmonies. My recollections are of contrasts like those

of life—joy and sadness, poverty and ease.

And the pictures are full of faces, many of which may be seen no

more by earthly vision. I miss the clasp of vanished hands, I

crave the sound of voices stilled. As we old and older grow,

there is a note of sadness in our glee. Whether we will or not we

must twine the cypress with the holly. The recollection of each

passing year brings deeper regret. How many have gone from those

circles that we recall when we were children? How many little

feet that pattered upon the stair on Christmas morning now tread

softer paths and walk in broader ways; sisters and brothers who

used to come back from the far countries to the old home—alas,

they cannot come from the farther country in which they now are,

and perhaps, saddest thought of all, we would not wish them to

come again. How many, with whom we joined hands around the

Christmas tree, have gone?

Circles are broken, families are separated, loved ones are lost,

but the old world sweeps on. Others come to take our places. As

we stood at the knee of some unforgotten mother, so other

children stand. As we listened to the story of the Christ Child

from the lips of some grey old father, so other children listen

and we ourselves perchance are fathers or mothers too. Other

groups come to us for the deathless story. Little heads which

recall vanished halcyon days of youth bend around another younger

mother. Smaller hands than ours write letters to Santa Claus and

hear the story, the sweetest story ever told, of the Baby who

came to Mary and through her to all the daughters and sons of

women on that winter night on the Bethlehem hills.

And we thank God for the children who take us out of the past,

out of ourselves, away from recollections that weigh us down; the

children that weave in the woof and warp of life when our own

youth has passed, some of the buoyancy, the joy, the happiness of

the present; the children in whose opening lives we turn

hopefully to the future. We thank God at this Christmas season

that it pleased Him to send His beloved Son to come to us as a

little child, like any other child. We thank God that in the

lesser sense we may see in every child who comes to-day another

incarnation of divinity. We thank God for the portion of His

Spirit with which He dowers every child of man, just as we thank

Him for pouring it all upon the Infant in the Manger.

There is no age that has not had its prophet. No country, no

people, but that has produced its leader. But did any of them

ever before come as a little child? Did any of them begin to lead

while yet in arms? Lodges there upon any other baby brow “the

round and top of sovereignty?” What distinguished Christ and His

Christian followers from all the world? Behold! no mighty

monarch, but “a little child shall lead them!”

You may see through the glass darkly, you may not know or

understand the blessedness of faith in Him as He would have you

know it, but there is nothing that can dim the light that

radiates from that birth in the rude cave back of the inn. Ah, it

pierces through the darkness of that shrouding night. It shines

to-day. Still sparkles the Star in the East. He is that Star.

There is nothing that can take from mankind—even doubting

mankind—the spirit of Christ and the Christmas season. Our

celebrations do not rest upon the conclusions of logic, or the

demonstrations of philosophy; I would not even argue that they

depend inevitably or absolutely upon the possession of a certain

faith in Jesus, but we accept Christmas, nevertheless; we

endeavour to apply the Christmas spirit, for just once in the

year; it may be because we cannot, try as we may, crush out

utterly and entirely the divinity that is in us that makes for

God. The stories and tales for Christmas which have for their

theme the hard heart softened are not mere fictions of the

imagination. They rest upon an instinctive consciousness of a

profound philosophic truth.

What is the unpardonable sin, I wonder? Is it to be persistently

and forever unkind? Does it mean perhaps the absolute refusal to

accept the principle of love which is indeed creation’s final

law? The lessons of the Christmastide are so many; the appeals

that now may be made to humanity crowd to the lips from full

minds and fuller hearts. Might we not reduce them all to the

explication of the underlying principle of God’s purpose to us,

as expressed in those themic words of love with which angels and

men greeted the advent of the Child on the first Christmas

morning, “Good will toward men?”

Let us then show our good will toward men by doing good and

bringing happiness to someone—if not to everyone—at this

Christmas season. Put aside the memories of disappointments, of

sorrows that have not vanished, of cares that still burden, and

do good in spite of them because you would not dim the brightness

of the present for any human heart with the shadows of old

regrets. Do good because of a future which opens possibilities

before you, for others, if not for yourselves.

Brethren, friends, all, let us make up our minds that we will be

kindly affectioned one to another in our homes and out of them,

on this approaching Christmas day. That the old debate, the

ancient strife, the rankling recollection, the sharp contention,

shall be put aside, that “envy, hatred, and malice, and all

uncharitableness” shall be done away with. Let us forgive and

forget; but if we cannot forget let us at least forgive. And so

let there be peace between man and man at Christmas—a truce of

God.

Let us pray that Love shall come as a little child to our

households. That He shall be in our hearts and shall find His

expression in all that we do or say on this birthday of goodness

and cheer for the world. Then let us resolve that the spirit of

the day shall be carried out through our lives, that as Christ

did not come for an hour, but for a lifetime, we would fain

become as little children on this day of days that we may begin a

new life of good will to men.

Let us make this a new birthday of kindness and love that shall

endure. That is a Christmas hope, a Christmas wish. Let us give

to it the gracious expression of life among men.

[Illustration]

[Illustration]

FROM A FAR COUNTRY

_Being a New Variation of an Ancient Theme_

A STORY FOR GROWN-UPS

I

“_A certain man had two sons_”—so begins the best and most famous

story in the world’s literature. Use of the absolute superlative

is always dangerous, but none will gainsay that statement, I am

sure. This story, which follows that familiar tale afar off,

indeed, begins in the same way. And the parallelism between the

two is exact up to a certain point. What difference a little

point doth make; like the little fire, behold, how great a matter

it kindleth! Indeed, lacking that one detail the older story

would have had no value; it would not have been told; without its

addition this would have been a repetition of the other.

When the modern young prodigal came to himself, when he found

himself no longer able to endure the husks of the swine like his

ancient exemplar, when he rose and returned to his father because

of that distaste, he found no father watching and waiting for him

at the end of the road! Upon that change the action of this story

hangs. It was a pity, too, because the elder brother was there

and in a mood not unlike that of his famous prototype.

Indeed, there was added to that elder brother’s natural

resentment at the younger’s course the blinding power of a great

sorrow, for the father of the two sons was dead. He had died of a

broken heart. Possessed of no omniscience of mind or vision, he

had been unable to foresee the long delayed turning point in the

career of his younger son and death came too swiftly to enable

them to meet again. So long as he had strength, that father had

stood, as it were, at the top of the hill looking down the road

watching and hoping.

And but the day before the tardy prodigal’s return he had been

laid away with his own fathers in the God’s acre around the

village church in the Pennsylvania hills. Therefore there was no

fatted calf ready for the disillusioned youth whose waywardness

had killed his father. It will be remembered that the original

elder brother objected seriously to fatted calves on such

occasions. Indeed, the funeral baked meats would coldly furnish

forth a welcoming meal if any such were called for.

For all his waywardness, for all his self-will, the younger son

had loved his father well, and it was a terrible shock to him

(having come to his senses) to find that he had returned too

late. And for all his hardness and narrowness the eldest son also

had loved his father well—strong tribute to the quality of the

dead parent—and when he found himself bereft he naturally visited

wrath upon the head of him who he believed rightly was the cause

of the untimely death of the old man.

As he sat in the study, if such it might be called, of the

departed, before the old-fashioned desk with its household and

farm and business accounts, which in their order and method and

long use were eloquent of his provident and farseeing father, his

heart was hot within his breast. Grief and resentment alike

gnawed at his vitals. They had received vivid reports, even in

the little town in which they dwelt, of the wild doings of the

wanderer, but they had enjoyed no direct communication with him.

After a while even rumour ceased to busy itself with the doings

of the youth. He had dropped out of their lives utterly after he

passed over the hills and far away.

The father had failed slowly for a time, only to break suddenly

and swiftly in the end. And the hurried frantic search for the

missing had brought no results. Ironically the god of chance had

led the young man’s repentant footsteps to the door too late.

“Where’s father?” cried John Carstairs to the startled woman who

stared at him as if she had seen a ghost as, at his knock, she

opened the door which he had found locked, not against him, but

the hour was late and it was the usual nightly precaution:

“Your brother is in your father’s study, sir,” faltered the

servant at last.

“Umph! Will,” said the man, his face changing. “I’d rather see

father first.”

“I think you had better see Mr. William, sir.”

“What’s the matter, Janet?” asked young Carstairs anxiously. “Is

father ill?”

“Yes, sir! indeed I think you had bettor see Mr. William at once,

Mr. John.”

Strangely moved by the obvious agitation of the ancient servitor

of the house who had known him from childhood, John Carstairs

hurried down the long hall to the door of his father’s study.

Always a scapegrace, generally in difficulties, full of mischief,

he had approached that door many times in fear of well merited

punishment which was sure to be meted out to him. And he came to

it with the old familiar apprehension that night, if from a

different cause. He never dreamed that his father was anything

but ill. He must see his brother. He stood in no little awe of

that brother, who was his exact antithesis in almost everything.

They had not got along particularly well. If his father had been

inside the door he would have hesitated with his hand on the

knob. If his father had not been ill he would not have attempted

to face his brother. But his anxiety, which was increased by a

sudden foreboding, for Janet, the maid, had looked at him so

strangely, moved him to quick action. He threw the door open

instantly. What he saw did not reassure him. William was clad in

funeral black. He wore a long frock coat instead of the usual

knockabout suit he affected on the farm. His face was white and

haggard. There was an instant interchange of names.

“John!”

“William!”

And then—

“Is father ill?” burst out the younger.

“Janet said—”

“Dead!” interposed William harshly, all his indignation flaming

into speech and action as he confronted the cause of the

disaster.

“Dead! Good God!”

“God had nothing to do with it.”

“You mean?”

“You did it.”

“I?”

“Yes. Your drunken revelry, your reckless extravagance, your

dissipation with women, your unfeeling silence, your—”

“Stop!” cried the younger. “I have come to my senses, I can’t

bear it.”

“I’ll say it if it kills you. You did it, I repeat. He longed and

prayed and waited and you didn’t come. You didn’t write. We could

hear nothing. The best father on earth.”

The younger man sank down in a chair and covered his face with

his hands.

“When?” he gasped out finally.

“Three days ago.”

“And have you—”

“He is buried beside mother in the churchyard yonder. Now that

you are here I thank God that he didn’t live to see what you have

become.”

The respectable elder brother’s glance took in the disreputable

younger, his once handsome face marred—one doesn’t foregather

with swine in the sty without acquiring marks of the

association—his clothing in rags. Thus errant youth, that was

youth no longer, came back from that far country. Under such

circumstances one generally has to walk most of the way. He had

often heard the chimes at midnight, sleeping coldly in the straw

stack of the fields, and the dust of the road clung to his

person. Through his broken shoes his bare feet showed, and he

trembled visibly as the other confronted him, partly from hunger

and weakness and shattered nerves, and partly from shame and

horror and for what reason God only knew.

The tall, handsome man in the long black coat, who towered over

him so grimly stern, was two years older than he, yet to the

casual observer the balance of time was against the prodigal by

at least a dozen years. However, he was but faintly conscious of

his older brother. One word and one sentence rang in his ear.

Indeed, they beat upon his consciousness until he blanched and

quivered beneath their onslaught.

“Dead—you did it!”

Yes, it was just. No mercy seasoned that justice in the heart of

either man. The weaker, self-accusing, sat silent with bowed

head, his conscience seconding the words of the stronger. The

voice of the elder ran on with growing, terrifying intensity.

“Please stop,” interposed the younger. He rose to his feet. “You

are right, Will. You were always right and I was always wrong. I

did kill him. But you need not have told me with such bitterness.

I realized it the minute you said he was dead. It’s true. And yet

I was honestly sorry. I came back to tell him so, to ask his

forgiveness.”

“When your money was gone.”

“You can say that, too,” answered the other, wincing under the

savage thrust. “It’s as true as the rest probably, but sometimes

a man has to get down very low before he looks up. It was that

way with me. Well, I’ve had my share and I’ve had my fling. I’ve

no business here. Good-bye.” He turned abruptly away.

“Don’t add more folly to what you have already done,” returned

William Carstairs, and with the beginnings of a belated pity, he

added, “stay here with me, there will be enough for us both and—”

“I can’t.”

“Well, then,” he drew out of his pocket a roll of bills, “take

these and when you want more—”

“Damn your money,” burst out John Carstairs, passionately. He

struck the other’s outstretched hand, and in his surprise,

William Carstairs let the bills scatter upon the floor. “I don’t

want it—blood money. Father is dead. I’ve had mine. I’ll trouble

you no more.”

He turned and staggered out of the room. Now William Carstairs

was a proud man and John Carstairs had offended him deeply. He

believed all that he had said to his brother, yet there had been

developing a feeling of pity for him in his heart, and in his

cold way he had sought to express it. His magnanimity had been

rejected with scorn. He looked down at the scattered bills on the

floor. Characteristically—for he inherited his father’s business

ability without his heart—he stooped over and picked them slowly

up, thinking hard the while. He finally decided that he would

give his brother yet another chance for his father’s sake. After

all, they were brethren. But the decision came too late. John

Carstairs had stood not on the order of his going, but had gone

at once, none staying him.

William Carstairs stood in the outer door, the light from the

hall behind him streaming out into the night. He could see

nothing. He called aloud, but there was no answer. He had no idea

where his younger brother had gone. If he had been a man of finer

feeling or quicker perception, perhaps if the positions of the

two had been reversed and he had been his younger brother, he

might have guessed that John might have been found beside the

newest mound in the churchyard, had one sought him there. But

that idea did not come to William, and after staring into the

blackness for a long time, he reluctantly closed the door.

Perhaps the vagrant could be found in the morning.

No, there had been no father waiting for the prodigal at the end

of the road, and what a difference it had made to that wanderer

and vagabond!

II

We leave a blank line on the page and denote thereby that ten

years have passed. It was Christmas Eve, that is, it had been

Christmas Eve when the little children had gone to bed. Now

midnight had passed and it was already Christmas morning. In one

of the greatest and most splendid houses on the avenue two little

children were nestled all snug in their beds in a nursery. In an

adjoining room sound sleep had quieted the nerves of the usually

vigilant and watchful nurse. But the little children were

wakeful. As always, visions of Santa Claus danced in their heads.

They were fearless children by nature and had been trained

without the use of bugaboos to keep them in the paths wherein

they should go. On this night of nights they had left the doors

of their nursery open. The older, a little girl of six, was

startled, but not alarmed, as she lay watchfully waiting, by a

creaking sound as of an opened door in the library below. She

listened with a beating heart under the coverlet; cause of

agitation not fear, but hope. It might be, it must be Santa

Claus, she decided. Brother, aged four, was close at hand in his

own small crib. She got out of her bed softly so as not to

disturb Santa Claus, or—more important at the time—the nurse. She

had an idea that Saint Nicholas might not welcome a nurse, but

she had no fear at all that he would not be glad to see her.

Need for a decision confronted her. Should she reserve the

pleasure she expected to derive from the interview for herself or

should she share it with little brother? There was a certain risk

in arousing brother. He was apt to awaken clamant, vociferous.

Still, she resolved to try it. For one thing, it seemed so

selfish to see Santa Claus alone, and for another the adventure

would be a little less timorous taken together.

Slipping her feet into her bedroom slippers and covering her

nightgown with a little blanket wrap, she tip-toed over to

brother’s bed. Fortunately, he too was sleeping lightly, and for

a like reason. For a wonder she succeeded in arousing him without

any outcry on his part. He was instantly keenly, if quietly,

alive to the situation and its fascinating possibilities.

“You must be very quiet, John,” she whispered. “But I think Santa

Claus is down in the library. We’ll go down and catch him.”

Brother, as became the hardier male, disdained further protection

of his small but valiant person. Clad only in his pajamas and his

slippers, he followed sister out the door and down the stair.

They went hand in hand, greatly excited by the desperate

adventure.

What proportion of the millions who dwelt in the great city were

children of tender years only statisticians can say, but

doubtless there were thousands of little hearts beating with

anticipation as the hearts of those children beat, and perhaps

there may have been others who were softly creeping downstairs to

catch Santa Claus unawares at that very moment.

One man at least was keenly conscious of one little soul who,

with absolutely nothing to warrant the expectation, nothing

reasonable on which to base joyous anticipation, had gone to bed

thinking of Santa Claus and hoping that, amidst equally deserving

hundreds of thousands of obscure children, this little mite in

her cold, cheerless garret might not be overlooked by the

generous dispenser of joy. With the sublime trust of childhood

she had insisted upon hanging up her ragged stocking. Santa Claus

would have to be very careful indeed lest things should drop

through and clatter upon the floor. Her heart had beaten, too,

although she descended no stair in the great house. She, too, lay

wakeful, uneasy, watching, sleeping, drowsing, hoping. We may

have some doubts about the eternal springing of hope in the human

breast save in the case of childhood—thank God it is always

verdant there!

III

Now few people get so low that they do not love somebody, and I

dare say that no people get so low that somebody does not love

them.

“Crackerjack,” so called because of his super-excellence in his

chosen profession, was, or had been, a burglar and thief; a very

ancient and highly placed calling indeed. You doubtless remember

that two thieves comprised the sole companions and attendants of

the Greatest King upon the most famous throne in history. His

sole court at the culmination of His career. “Crackerjack” was no

exception to the general rule about loving and being beloved set

forth above.

He loved the little lady whose tattered stocking swung in the

breeze from the cracked window. Also he loved the wretched woman

who with himself shared the honours of parentage to the poor but

hopeful mite who was also dreaming of Christmas and the morning.

And his love inspired him to action. Singular into what devious

courses, utterly unjustifiable, even so exalted and holy an

emotion may lead fallible man. Love—burglary! They do not belong

naturally in association, yet slip cold, need, and hunger in

between and we may have explanation even if there be no

justification. Oh, Love, how many crimes are committed in thy

name!

“Crackerjack” would hardly have chosen Christmas eve for a

thieving expedition if there had been any other recourse.

Unfortunately there was none. The burglar’s profession, so far as

he had practised it, was undergoing a timely eclipse. Time was

when it had been lucrative, its rewards great. Then the law,

which is no respecter of professions of that kind, had got him.

“Crackerjack” had but recently returned from a protracted sojourn

at an institution arranged by the State in its paternalism for

the reception and harbouring of such as he. The pitiful dole with

which the discharged prisoner had been unloaded upon a world

which had no welcome for him had been soon spent; even the

hideous prison-made clothes had been pawned, and some rags, which

were yet the rags of a free man, which had been preserved through

the long period of separation by his wife, gave him a poor

shelter from the winter’s cold.

That wife had been faithful to him. She had done the best she

could for herself and baby during the five years of the absence

of the bread winner, or in his case the bread taker would be the

better phrase. She had eagerly waited the hour of his release;

her joy had been soon turned to bitterness. The fact that he had

been in prison had shut every door against him and even closed

the few that had been open to her. The three pieces of human

flotsam had been driven by the wind of adversity and tossed. They

knew not where to turn when jettisoned by society.

Came Christmas Eve. They had no money and no food and no fire.

Stop! The fire of love burned in the woman’s heart, the fire of

hate in the man’s. Prison life usually completes the education in

shame of the unfortunate men who are thrust there. This was

before the days in which humane men interested themselves in

prisons and prisoners and strove to awaken the world to its

responsibilities to, as well as the possibilities of, the

convict.

But “Crackerjack” was a man of unusual character. Poverty,

remorse, drink, all the things that go to wreck men by forcing

them into evil courses had laid him low, and because he was a man

originally of education and ability, he had shone as a criminal.

The same force of character which made him super-burglar could

change him from criminal to man if by chance they could be

enlisted in the endeavour.

He had involved the wife he had married in his misfortunes. She

had been a good woman, weaker than he, yet she stuck to him. God

chose the weak thing to rejuvenate the strong. In the prison he

had enjoyed abundant leisure for reflection. After he learned of

the birth of his daughter he determined to do differently when he

was freed. Many men determine, especially in the case of an

ex-convict, but society usually determines better—no, not better,

but more strongly. Society had different ideas. It was

Brahministic in its religion. Caste? Yes, once a criminal always

a criminal.

“Old girl,” said the broken man, “it’s no use. I’ve tried to be

decent for your sake and the kid’s, but it can’t be done. I can’t

get honest work. They’ve put the mark of Cain on me. They can

take the consequences. The kid’s got to have some Christmas;

you’ve got to have food and drink and clothes and fire. God, how

cold it is! I’ll go out and get some.”

“Isn’t there something else we can pawn?”

“Nothing.”

“Isn’t there any work?”

“Work?” laughed the man bitterly. “I’ve tramped the city over

seeking it, and you, too. Now, I’m going to get money—elsewhere.”

“Where?”

“Where it’s to be had.”

“Oh, Jack, think.”

“If I thought, I’d kill you and the kid and myself.”

“Perhaps that would be better,” said the woman simply. “There

doesn’t seem to be any place left for us.”

“We haven’t come to that yet,” said the man. “Society owes me a

living and, by God, it’s got to pay it to me.”

It was an oft-repeated, widely held assertion, whether fallacious

or not each may determine for himself.

“I’m afraid,” said the woman.

“You needn’t be; nothing can be worse than this hell.”

He kissed her fiercely. Albeit she was thin and haggard she was

beautiful to him. Then he bent over his little girl. He had not

yet had sufficient time since his release to get very well

acquainted with her. She had been born while he was in prison,

but it had not taken any time at all for him to learn to love

her. He stared at her a moment. He bent to kiss her and then

stopped. He might awaken her. It is always best for the children

of the very poor to sleep. He who sleeps dines, runs the Spanish

proverb. He turned and kissed the little ragged stockings

instead, and then he went out. He was going to play—was it Santa

Claus, indeed?

IV

The strange, illogical, ironical god of chance, or was it

Providence acting through some careless maid, had left an area

window unlocked in the biggest and newest house on the avenue.

Any house would have been easy for “Crackerjack” if he had

possessed the open sesame of his kit of burglar’s tools, but he

had not had a jimmy in his hand since he was caught with one and

sent to Sing Sing. He had examined house after house, trusting to

luck as he wandered on, and, lo! fortune favoured him.

The clock in a nearby church struck the hour of two. The areaway

was dark. No one was abroad. He plunged down the steps, opened

the window and disappeared. No man could move more noiselessly

than he. In the still night he knew how the slightest sounds are

magnified. He had made none as he groped his way through the back

of the house, arriving at last in a room which he judged to be

the library. Then, after listening and hearing nothing, he

ventured to turn the button of a side light in a far corner of

the room.

He was in a large apartment, beautifully furnished. Books and

pictures abounded, but these did not interest him, although if he

had made further examination he might have found things worthy of

his attention even there. It so happened that the light bracket

to which he had blundered, or had been led, was immediately over

a large wall safe. Evidently it had been placed there for the

purpose of illuminating the safe door. His eyes told him that

instantly. This was greater fortune than he expected. A wall safe

in a house like that must contain things of value.

Marking the position of the combination knob, he turned out the

light and waited again. The quiet of the night continued

unbroken. A swift inspection convinced him that the lock was only

an ordinary combination. With proper—or improper—tools he could

have opened it easily. Even without tools, such were his

delicately trained ear and his wonderfully trained fingers that

he thought he could feel and hear the combination. He knelt down

by the knob and began to turn it slowly, listening and feeling

for the fall of the tumblers. Several times he almost got it,

only to fail at the end, but by repeated trials and unexampled

patience, his heart beating like a trip-hammer the while, he

finally mastered the combination and opened the safe door.

In his excitement when he felt the door move he swung it outward

sharply. It had not been used for some time evidently and the

hinges creaked. He checked the door and listened again. Was he to

be balked after so much success? He was greatly relieved at the

absence of sound. It was quite dark in the room. He could see

nothing but the safe. He reached his hand in and discovered it

was filled with bulky articles covered with some kind of cloth,

silver evidently.

He decided that he must have a look and again he switched on the

light. Yes, his surmise had been correct. The safe was filled

with silver. There was a small steel drawer in the middle of it.

He had a broad bladed jack-knife in his pocket and at the risk of

snapping the blade he forced the lock and drew out the drawer. It

was filled with papers. He lifted the first one and stood staring

at it in astonishment, for it was an envelope which bore his

name, written by a hand which had long since mouldered away in

the dust of a grave.

V

Before he could open the envelope, there broke on his ear a still

small voice, not that of conscience, not that of God; the voice

of a child—but does not God speak perhaps as often through the

lips of childhood as in any other way—and conscience, too?

“Are you Santa Claus?” the voice whispered in his ear.

“Crackerjack” dropped the paper and turned like a flash, knife

upraised in his clenched hand, to confront a very little girl and

a still smaller boy staring at him in open-eyed astonishment, an

astonishment which was without any vestige of alarm. He looked

down at the two and they looked up at him, equal bewilderment on

both sides.

“I sought dat Santy Claus tame down de chimney,” said the younger

of the twain, whose pajamas bespoke the nascent man.

“In all the books he has a long white beard. Where’s yours?”

asked the coming woman.

This innocent question no less than the unaffected simplicity and

sincerity of the questioner overpowered “Crackerjack.” He sank

back into a convenient chair and stared at the imperturbable

pair. There was a strange and wonderful likeness in the

sweet-faced golden-haired little girl before him to the worn,

haggard, and ill-clad little girl who lay shivering in the mean

bed in the upper room where God was not—or so he fancied.

“You’re a little girl, aren’t you?” he whispered.

No voice had been or was raised above a whisper. It was a

witching hour and its spell was upon them all.

“Yes.”

“What is your name?”

“Helen.”

Now Helen had been “Crackerjack’s” mother’s name and it was the

name of his own little girl, and although everybody else called

her Nell, to him she was always Helen.

“And my name’s John,” volunteered the other child.

“John!” That was extraordinary!

“What’s your other name?”

“John William.”

The man stared again. Could this be coincidence merely? John was

his own name and William that of his brother.

“I mean what is your last name?”

“Carstairs,” answered the little girl. “Now you tell us who you

are. You aren’t Santa Claus, are you? I don’t hear any reindeers

outside, or bells, and you haven’t any pack, and you’re not by

the fireplace where our stockings are.”

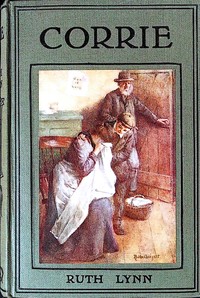

[Illustration: I sought dat Santy Claus tame down de chimney,” said the

younger of the twain.] “I sought dat Santy Claus tame down de chimney,”

said the younger of the twain.

“No,” said the man, “I’m not exactly Santa Claus, I’m his

friend—I—”

What should he say to these children? In his bewilderment for the

moment he actually forgot the letter which he still held tightly

in his hand.

“Dat’s muvver’s safe,” continued the little boy. “She keeps lots

o’ things in it. It’s all hers but dat drawer. Dat’s papa’s and—”

“I think I hear some one on the stairs,” broke in the little girl

suddenly in great excitement. “Maybe that’s Santa Claus.”

“Perhaps it is,” said the man, who had also heard. “You wait and

watch for him. I’ll go outside and attend to his reindeer.”

He made a movement to withdraw, but the girl caught him tightly

by the hand.

“If you are his friend,” she said, “you can introduce us. You

know our names and—”

The golden opportunity was gone.

“Don’t say a word,” whispered the man quickly. “We’ll surprise

him. Be very still.”

He reached his hand up and turned out the light. He half hoped he

might be mistaken, or that in the darkness they would not be

seen, but no. They all heard the footsteps on the stair. They

came down slowly, and it was evident that whoever was approaching

was using every precaution not to be heard. “Crackerjack” was in

a frightful situation. He did not know whether to jerk himself

away from the two children, for the boy had clasped him around

the leg and the girl still held his hand, or whether to wait.

The power of decision suddenly left him, for the steps stopped

before the door. There was a little click as a hand pressed a

button on the wall and the whole room was flooded with light from

the great electrolier in the centre. Well, the game was up.

“Crackerjack” had been crouching low with the children. He rose

to his feet and looked straightly enough into the barrel of a

pistol held by a tall, severe looking man in a rich silk dressing

robe, who confronted him in the doorway. Two words broke from the

lips of the two men, the same words that had fallen from their

lips when they met ten years before.

“John!” cried the elder man, laying the weapon on a nearby table.

“Will!” answered “Crackerjack” in the same breath.

As if to mark the eternal difference as before, the one was

clothed in habiliments of wealth and luxury, the other in the

rags and tatters of poverty and shame.

“Why, that isn’t Santa Claus,” instantly burst out the little

girl, “that’s papa.”

“Dis is Santy Claus’s friend, papa,” said the little boy. “We

were doin’ to su’prise him. He said be very still and we minded.”

“So this is what you have come to, John,” said the elder man, but

there was an unwonted gentleness in his voice.

“I swear to God I didn’t know it was your house. I just came in

here because the window was open.”

The other pointed to the safe.

“But you were—”

“Of course I was. You don’t suppose I wandered in for fun, do

you? I’ve got a little girl of my own, and her name’s Helen, too;

our mother’s name.”

The other brother nodded.

“She’s hungry and cold and there’s no Christmas for her or her

mother.”

“Oh, Santy has been here already,” cried Master John Williams,

running toward the great fireplace, having just that moment

discovered the bulging stockings and piles of gifts. His sister

made a move in the same direction, for at the other corner hung

her stocking and beneath it her pile, but the man’s hand

unconsciously tightened upon her hand and she stopped.

“I’ll stay with you,” she said, after a moment of hesitation.

“Tell me more about your Helen.”

“There’s nothing to tell.” He released her hand roughly. “You

musn’t touch me,” he added harshly. “Go.”

“You needn’t go, my dear,” said her father quickly. “Indeed, I

think, perhaps—”

“Is your Helen very poor?” quietly asked the little girl,

possessing herself of his hand again, “because if she is she can

have”—she looked over at the pile of toys—“Well, I’ll see. I’ll

give her lots of things, and—”

“What’s this?” broke out the younger man harshly, extending his

hand with the letter in it toward the other.

“It is a letter to you from our father.”

“And you kept it from me?” cried the other.

“Read it,” said William Carstairs.

With trembling hands “Crackerjack” tore it open. It was a message

of love and forgiveness penned by a dying hand.

“If I had had this then I might have been a different man,” said

the poor wretch.

“There is another paper under it, or there should be, in the same

drawer,” went on William Carstairs, imperturbably. “Perhaps you

would better read that.”

John Carstairs needed no second invitation. He turned to the open

drawer and took out the next paper. It was a copy of a will. The

farm and business had been left to William, but one half of it

was to be held in trust for his brother. The man read it and then

he crushed the paper in his hand.

“And that, too, might have saved me. My God!” he cried, “I’ve

been a drunken blackguard. I’ve gone down to the very depths. I

have been in State’s prison. I was, I am, a thief, but I never

would have withheld a dying man’s forgiveness from his son. I

never would have kept a poor wretch who was crazy with shame and

who drank himself into crime out of his share of the property.”

Animated by a certain fell purpose, he leaped across the room and

seized the pistol.

“Yes, and I have you now!” he cried. “I’ll make you pay.”

He levelled the weapon at his brother with a steady hand.

“What are you doin’ to do wif that pistol?” said young John

William, curiously looking up from his stocking, while Helen

cried out. The little woman acted the better part. With rare

intuition she came quickly and took the left hand of the man and

patted it gently. For one thing, her father was not afraid, and

that reassured her. John Carstairs threw the pistol down again.

William Carstairs had never moved.

“Now,” he said, “let me explain.”

“Can you explain away this?”

“I can. Father’s will was not opened until the day after you

left. As God is my judge I did not know he had written to you. I

did not know he had left anything to you. I left no stone

unturned in an endeavour to find you. I employed the best

detectives in the land, but we found no trace of you whatever.

Why, John, I have only been sorry once that I let you go that

night, that I spoke those words to you, and that has been all the

time.”

“And where does this come from?” said the man, flinging his arm

up and confronting the magnificent room.

“It came from the old farm. There was oil on it and I sold it for

a great price. I was happily married. I came here and have been

successful in business. Half of it all is yours.”

“I won’t take it.”

“John,” said William Carstairs, “I offered you money once and you

struck it out of my hand. You remember?”

“Yes.”

“What I am offering you now is your own. You can’t strike it out

of my hand. It is not mine, but yours.”

“I won’t have it,” protested the man. “It’s too late. You don’t

know what I’ve been, a common thief. ‘Crackerjack’ is my name.

Every policeman and detective in New York knows me.”

“But you’ve got a little Helen, too, haven’t you?” interposed the

little girl with wisdom and tact beyond her years.

“Yes.”

“And you said she was very poor and had no Christmas.”

“Yes.”

“For her sake, John,” said William Carstairs. “Indeed you must

not think you have been punished alone. I have been punished,

too. I’ll help you begin again. Here”—he stepped closer to his

brother—“is my hand.”

The other stared at it uncomprehendingly.

“There is nothing in it now but affection. Won’t you take it?”

Slowly John Carstairs lifted his hand. His palm met that of his

elder brother. He was so hungry and so weak and so overcome that

he swayed a little. His head bowed, his body shook and the elder

brother put his arm around him and drew him close.

Into the room came William Carstairs’ wife. She, too, had at last

been aroused by the conversation, and, missing her husband, she

had thrown a wrapper about her and had come down to seek him.

“We tame down to find Santy Claus,” burst out young John William,

at the sight of her, “and he’s been here, look muvver.”

Yes, Santa Claus had indeed been there. The boy spoke better than

he knew.

“And this,” said little Helen eagerly, pointing proudly to her

new acquaintance, “is a friend of his, and he knows papa and he’s

got a little Helen and we’re going to give her a Merry

Christmas.”

William Carstairs had no secrets from his wife. With a flash of

womanly intuition, although she could not understand how he came

to be there, she divined who this strange guest was who looked a

pale, weak picture of her strong and splendid husband, and yet

she must have final assurance.

“Who is this gentleman, William?” she asked quietly, and John

Carstairs was forever grateful to her for her word that night.

“This,” said William Carstairs, “is my father’s son, my brother,

who was dead and is alive again, and was lost and is found.”

And so, as it began with the beginning, this story ends with the

ending of the best and most famous of all the stories that were

ever told.

[Illustration]

[Illustration]

ON CHRISTMAS GIVING

_Being a Word of Much Needed Advice_

Christmas is the birthday of our Lord, upon which we celebrate

God’s ineffable gift of Himself to His children. No human soul

has ever been able to realize the full significance of that gift,

no heart has ever been glad enough to contain the joy of it, and

no mind has ever been wise enough to express it. Nevertheless we

powerfully appreciate the blessing and would fain convey it

fitly. Therefore to commemorate that great gift the custom of

exchanging tokens of love and remembrance has grown until it has

become well nigh universal. This is a day in which we ourselves

crave, as never at any other time, happiness and peace for those

we love and that ought to include everybody, for with the angelic

message in our ears it should be impossible to hate any one on

Christmas day however we may feel before or after.

But despite the best of wills almost inevitably Christmas in many

instances has created a burdensome demand. Perhaps by the method

of exclusion we shall find out what Christmas should be. It is

not a time for extravagance, for ostentation, for vulgar display,

it is possible to purchase pleasure for someone else at too high

a price to ourselves. To paraphrase Polonius, “Costly thy gift as

thy purse can buy, rich but not expressed in fancy, for the gift

oft proclaims the man.” In making presents observe three

principal facts; the length of your purse, the character of your

friend, and the universal rule of good taste. Do not plunge into

extravagance from which you will scarcely recover except in

months of nervous strain and desperate financial struggle. On the

other hand do not be mean and niggardly in your gifts. Oh, not

that; avoid selfishness at Christmas, if at no other time. Rather

no gift at all than a grudging one. Let your offerings represent

yourselves and your affections. Indeed if they do not represent

you, they are not gifts at all. “The gift without the giver is

bare.”

And above all banish from your mind the principle of reciprocity.

The _lex talionis_ has no place in Christmas giving. Do not think

or feel that you must give to someone because someone gave to

you. There is no barter about it. You give because you love and

without a thought of return. Credit others with the same feeling

and be governed thereby. I know one upon whose Christmas list

there are over one hundred and fifty people, rich and poor, high

and low, able and not able. That man would be dismayed beyond

measure if everyone of those people felt obliged to make a return

for the Christmas remembrances he so gladly sends them.

In giving remember after all the cardinal principle of the day.

Let your gift be an expression of your kindly remembrance, your

gentle consideration, your joyful spirit, your spontaneous

gratitude, your abiding desire for peace and goodwill toward men.

Hunt up somebody who needs and who without you may lack and

suffer heart hunger, loneliness, and disappointment.

Nor is Christmas a time for gluttonous eating and drinking. To

gorge one’s self with quantities of rich and indigestible food is

not the noblest method of commemorating the day. The rules and

laws of digestion are not abrogated upon the Holy day. These are

material cautions, the day has a spiritual significance of which

material manifestations are, or ought to be, outward and visible

expressions only.

Christmas is one of the great days of obligation in the Church

year, then as at Easter if at no other time, Christians should

gather around the table of the Lord, kneeling before God’s altar

in the ministering of that Holy Communion which unites them with

the past, the present, and the future—the communion of the saints

of God’s Holy Church with His Beloved Son. Then and thus in body,

soul, and spirit we do truly participate in the privilege and

blessing of the Incarnation, then and there we receive that

strength which enables everyone of us to become factors in the

great extension of that marvellous occurrence throughout the ages

and throughout the world.

Let us therefore on this Holy Natal Day, from which the whole

world dates its time, begin on our knees before that altar which

is at once manger, cross, throne. Let us join thereafter in holy

cheer of praise and prayer and exhortation and Christmas carol,

and then let us go forth with a Christmas spirit in our hearts

resolved to communicate it to the children of men, and not merely

for the day but for the future. To make the right use of these

our privileges, this it is to save the world.

In this spirit, therefore, so far as poor, fallible human nature

permits him to realize it and exhibit it, the author wishes all

his readers which at present comprise his only flock—

A MERRY CHRISTMAS AND A HAPPY NEW YEAR.

[Illustration]

[Illustration]

IT WAS THE SAME CHRISTMAS MORNING

_In Which it is Shown how Different the Same Things may Be_

_A Story for Girls_

In Philadelphia the rich and the poor live cheek by jowl—or

rather, back to back. Between the streets of the rich and

parallel to them, run the alleys of the poor. The rich man’s

garage jostles elbows with the poor man’s dwelling.

In a big house fronting on one of the most fashionable streets

lived a little girl named Ethel. Other people lived in the big

house also, a father, a mother, a butler, a French maid, and a

host of other servants. Back of the big house was the garage.

Facing the garage on the other side of the alley was a little,

old one-story-and-a-half brick house. In this house dwelt a

little girl named Maggie. With her lived her father who was a

labourer; her mother, who took in washing; and half a dozen

brothers, four of whom worked at something or other, while the

two littlest went to school.

Ethel and Maggie never played together. Their acquaintance was

simply a bowing one—better perhaps, a smiling one. From one

window in the big playroom which was so far to one side of the

house that Ethel could see past the garage and get a glimpse of

the window of the living-room in Maggie’s house, the two little

girls at first stared at each other. One day Maggie nodded and

smiled, then Ethel, feeling very much frightened, for she had

been cautioned against playing with or noticing the children in

the alley, nodded and smiled back. Now neither of the children

felt happy unless they had held a pantomimic conversation from

window to window at some time during the day.

It was Christmas morning. Ethel awoke very early, as all properly

organized children do on that day at least. She had a beautiful

room in which she slept alone. Adjacent to it, in another room

almost as beautiful, slept Celeste, her mamma’s French maid.

Ethel had been exquisitely trained. She lay awake a long time

before making a sound or movement, wishing it were time to arise.

But Christmas was strong upon her, the infection of the season

was in her blood. Presently she slipped softly out of bed,

pattered across the room, paused at the door which gave entrance

to the hall which led to her mother’s apartments, then turned and

plumped down upon Celeste.

“Merry Christmas,” she cried shaking the maid.

To awaken Celeste was a task of some difficulty. Ordinarily the

French woman would have been indignant at being thus summarily

routed out before the appointed hour but something of the spirit

of Christmas had touched her as well. She answered the salutation

of the little girl kindly enough, but as she sat up in bed she

lifted a reproving finger.

“But,” she said, “you mus’ keep ze silence, Mademoiselle Ethel.

Madame, vôtre maman, she say she mus’ not be disturb’ in ze

morning. She haf been out ver’ late in ze night and she haf go to

ze bed ver’ early. She say you mus’ be ver’ quiet on ze Matin de

Noël!”

“I will be quiet, Celeste,” answered the little girl, her lip

quivering at the injunction.

It was so hard to be repressed all the time but especially on

Christmas Day of all others.

“Zen I will help you to dress immediatement, and zen Villiam, he

vill call us to see ze tree.”

Never had the captious little girl been more docile, more

obedient. Dressing Ethel that morning was a pleasure to Celeste.

Scarcely had she completed the task and put on her own clothing

when there was a tap on the door.

“Vat is it?”

“Mornin’, Miss Celeste,” spoke a heavy voice outside, a voice

subdued to a decorous softness of tone, “if you an’ Miss Ethel

are ready, the tree is lit, an’—”

“Ve air ready, Monsieur Villiam,” answered Celeste, throwing open

the door dramatically.

Ethel opened her mouth to welcome the butler—for if that solemn

and portentous individual ever unbent it was to Miss Ethel, whom

in his heart of hearts he adored—but he placed a warning finger

to his lip and whispered in an awestruck voice:

“The master, your father, came in late last night, Miss, an’ he

said there must be no noise or racket this morning.”

Ethel nodded sadly, her eyes filling at her disappointment;

William then marched down the hall with a stately magnificence

peculiar to butlers, and opened the door into the playroom. He

flung it wide and stood to one side like a grenadier, as Celeste

and Ethel entered. There was a gorgeous tree, beautifully

trimmed. William had bought the tree and Celeste’s French taste

had adorned it. It was a sight to delight any child’s eyes and

the things strewn around it on the floor were even more

attractive. Everything that money could buy, that Celeste and

William could think of was there. Ethel’s mother had given her

maid carte blanche to buy the child whatever she liked, and

Ethel’s father had done the same with William. The two had pooled

their issue and the result was a toyshop dream. Ethel looked at

the things in silence.

“How do you like it, Miss?” asked William at last rather

anxiously.

“Mademoiselle is not pleased?” questioned the French woman.

“It—it—is lovely,” faltered the little girl.

“We haf selected zem ourselves.”

“Yes, Miss.”

“Didn’t mamma—buy anything—or papa—or Santa?”

“Zey tell us to get vatever you vould like and nevair mind ze

money.”

“It was so good of you, I am sure,” said Ethel struggling

valiantly against disappointment almost too great to bear.

“Everything is beautiful but—I—wish mamma or papa had—I wish they

were here—I’d like them to wish me a Merry Christmas.”

The little lip trembled but the upper teeth came down on it

firmly. The child had courage. William looked at Celeste and

Celeste shrugged her shoulders, both knowing what was lacking.

“I am sure, Miss, that they do wish you a Merry Christmas,

an’”—the butler began bravely, but the situation was too much for

him. “There goes the master’s bell,” he said quickly and turned

and stalked out of the room gravely, although no bell had

summoned him.

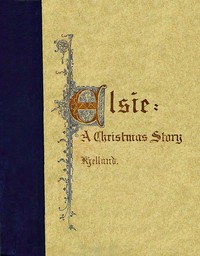

[Illustration: “I am sure, Miss, that they do wish you a Merry

Christmas.”]

“You may go, Celeste,” said Ethel with a dignity not unlike her

mother’s manner.

The maid shrugged her shoulders again, left the room and closed

the door. Everything was lovely, everything was there except that

personal touch which means so much even to the littlest girl.

Ethel was used to being cared for by others than her parents but

it came especially hard on her this morning. She turned, leaving

the beautiful things as they were placed about the tree, and

walked to the end window whence she could get a view of the

little house beyond the garage over the back wall.

There was a Christmas tree in Maggie’s house too. It wouldn’t

have made a respectable branch for Ethel’s tree, and the

trimmings were so cheap and poor that Celeste would have thrown

them into the waste basket immediately. There were a few common,

cheap, perishable little toys around the tree on the floor but to

Maggie it was a glimpse of heaven. She stood in her little white

night-gown—no such thing as dressing for her on Christmas

morning—staring around her. The whole family was grouped about

her, even the littlest brothers, who went to school because they

were not big enough to work, forgot their own joy in watching

their little sister. Her father, her mother, the big boys all in

a state of more or less dishevelled undress stood around her,

pointing out first one thing and then another which they had been

able to get for her by denying themselves some of the necessities

of life. Maggie was so happy that her eyes brimmed, yet she did

not cry. She laughed, she clapped her hands, and kissed them all

round and finally found herself, a big orange in one hand, a tin

trumpet in the other, perched upon her father’s broad shoulders

leading a frantic march around the narrow confines of the

living-room. As she passed by the one window she caught a glimpse

of the alley. It had been snowing throughout the night and the

ground was white.

“Oh,” she screamed with delight, “let me see the snow on

Christmas morning.”

Her father walked over to the window, parted the cheap lace

curtains, while Maggie clapped her hands gleefully at the

prospect. Presently she lifted her eyes and looked toward the

other window high up in the air, where Ethel stood, a mournful

little figure. Maggie’s papa looked too. He knew how cheap and

poor were the little gifts he had bought for his daughter.

“I wish,” he thought, “that she could have some of the things

that child up there has.”

Maggie however was quite content. She smiled, flourished her

trumpet, waved her orange, but there was no answering smile on

Ethel’s face now. Finally the wistful little girl in the big

house languidly waved her hand, and then Maggie was taken away to

be dressed lest she should catch cold after the mischief was

done.

“I hope that she’s having a nice Christmas,” said Maggie,

referring to Ethel.

“I hope so too,” answered her mother, wishing that her little

girl might have some of the beautiful gifts she knew must be in

the great house.

“Whatever she has,” said Maggie, gleefully, “she can’t have any

nicer Christmas than I have, that you and papa and the boys gave

me. I’m just as happy as I can be.”

Over in the big house, Ethel was also wishing. She was so unhappy

since she had seen Maggie in the arms of her big, bearded father,

standing by the window, that she could control herself no longer.

She turned away and threw herself down on the floor in front of

the tree and buried her face in her hands bursting into tears.

It was Christmas morning and she was all alone.

[Illustration]

[Illustration]

A CHRISTMAS CAROL

“_Christmas Then and Now_”

The Stars look down On David’s town, While angels sing in Winter night;

The Shepherds pray, And far away The Wise Men follow guiding light.

Little Christ Child By Mary Mild In Manger lies without the Inn;

Of Man the Son, Yet God in One, To save the lost in World of Sin.

Still stars look down

On David’s town And still the Christ Child dwells with men,

What thought give we To such as He, Or souls who live in Sin as then?

Show we our love To Him above By offering others’ grief to share;

And Christmas cheer For all the year Bestow to lighten pain and care.

[Illustration: The Stars Look Down (music page one)]

[Illustration: The Stars Look Down (music page two)]

[Illustration]

THE LONE SCOUT’S CHRISTMAS

_Wherein is Set Forth the Courage and Resourcefulness of Youth_

_A Story for Boys_

Every boy likes snow on Christmas Day, but there is such a thing

as too much of it. Henry Ives, alone in the long railroad coach,

stared out of the clouded windows at the whirling mass of snow

with feelings of dismay. It was the day before Christmas, almost

Christmas Eve. Henry did not feel any too happy, indeed he had

hard work to keep down a sob. His mother had died but a few weeks

before and his father, the captain of a freighter on the Great

Lakes, had decided, very reluctantly, to send him to his brother

who had a big ranch in western Nebraska.

Henry had never seen his uncle or his aunt. He did not know what

kind of people they were. The loss of his mother had been a

terrible blow to him and to be separated from his father had

filled his cup of sorrow to the brim. His father’s work did not

end with the close of navigation on the lakes, and he could not

get away then although he promised to come and see Henry before

the ice broke and traffic was resumed in the spring.

The long journey from the little Ohio town on Lake Erie to

western Nebraska had been without mishap. His uncle’s ranch lay

far away from the main line of the railroad on the end of the

branch. There was but one train a day upon it, and that was a

mixed train. The coach in which Henry sat was attached to the end

of a long string of freight cars. Travel was infrequent in that

section of the country. On this day Henry was the only passenger.

The train had been going up-grade for many miles and had just

about reached the crest of the divide. Bucking the snow had

become more and more difficult; several times the train had

stopped. Sometimes the engine backed the train some distance to

get headway to burst through the drift. So Henry thought nothing

of it when the car came to a gentle stop.

The all-day storm blew from the west and the front windows of the

car were covered with snow so he could not see ahead. Some time

before the conductor and rear brakeman had gone forward to help

dig the engine out of the drift and they had not come back.

Henry sat in silence for some time watching the whirling snow. He

was sad; even the thought of the gifts of his father and friends

in his trunk which stood in the baggage compartment of the car

did not cheer him. More than all the Christmas gifts in the

world, he wanted at that time his mother and father and friends.

“It doesn’t look as though it was going to be a very merry

Christmas for me,” he said aloud at last, and then feeling a

little stiff from having sat still so long he got up and walked

to the front of the car.

It was warm and pleasant in the coach. The Baker heater was going

at full blast and Henry noticed that there was plenty of coal. He

tried to see out from the front door; but as he was too prudent

to open it and let in the snow and cold he could make out

nothing. The silence rather alarmed him. The train had never

waited so long before.

Then, suddenly, came the thought that something very unusual was

wrong. He must get a look at the train ahead. He ran back to the

rear door, opened it and standing on the leeward side, peered

forward. The engine and freight cars were not there! All he saw

was the deep cut filled nearly to the height of the car with

snow.

Henry was of a mechanical turn of mind and he realized that

doubtless the coupling had broken. That was what had happened.

The trainmen had not noticed it and the train had gone on and

left the coach. The break had occurred at the crest of the divide

and the train had gone rapidly down hill on the other side. The

amount of snow told the boy that it would not be possible for the

train to back up and pick up the car. He was alone in the

wilderness of rolling hills in far western Nebraska. And this was

Christmas Eve!

It was enough to bring despair to any boy’s heart. But Henry Ives

was made of good stuff, he was a first-class Boy Scout and on his

scout coat in the trunk were four Merit Badges. He had the spirit

of his father, who had often bucked the November storms on Lake

Superior in his great six-hundred-foot freighter, and danger

inspired him.

He went back into the car, closed the door, and sat down to think

it over. He had very vague ideas as to how long such a storm

would last and how long he might be kept prisoner. He did not

even know just where he was or how far it was to the end of the

road and the town where his uncle’s ranch lay.

It was growing dark so he lighted one of the lamps close to the

heater and had plenty of light. In doing so he noticed in the

baggage rack a dinner pail. He remembered that the conductor had

told him that his wife had packed that dinner pail and although

it did not belong to the boy he felt justified in appropriating

it in such circumstances. It was full of food—eggs, sandwiches,

and a bottle of coffee. He was not very hungry but he ate a

sandwich. He was even getting cheerful about the situation

because he had something to do. It was an adventure.

While he had been eating, the storm had died away. Now he

discovered that it had stopped snowing. All around him the

country was a hilly, rolling prairie. The cut ran through a hill

which seemed to be higher than others in the neighbourhood. If he

could get on top of it he might see where he was. Although day

was ending it was not yet dark and Henry decided upon an

exploration.

Now he could not walk on foot in that deep and drifted snow

without sinking over his head under ordinary conditions, but his

troop had done a great deal of winter work, and strapped

alongside of his big, telescope grip were a pair of snow-shoes

which he himself had made, and with the use of which he was

thoroughly familiar.

“I mustn’t spoil this new suit,” he told himself, so he ran to

the baggage-room of the car, opened his trunk, got out his Scout

uniform and slipped into it in a jiffy. “Glad I ran in that

‘antelope dressing race,’” he muttered, “but I’ll beat my former

record now.” Over his khaki coat he put on his heavy sweater,

then donned his wool cap and gloves, and with his snow-shoes

under his arm hurried back to the rear platform. The snow was on

a level with the platform. It rose higher as the coach reached

into the cut. He saw that he would have to go down some distance

before he could turn and attempt the hill.

He had used his snow-shoes many times in play but this was the

first time they had ever been of real service to him. Thrusting

his toes into the straps he struck out boldly.

[Illustration: “Thrusting his toes into the straps he struck out

boldly.”]

To his delight he got along without the slightest difficulty

although he strode with great care. He gained the level and in

ten minutes found himself on the top of the hill, where he could

see miles and miles of rolling prairie. He turned himself slowly

about, to get a view of the country.

As his glance swept the horizon, at first it did not fall upon a

single, solitary thing except a vast expanse of snow. There was

not a tree even. The awful loneliness filled him with dismay. He

had about given up when, in the last quarter of the horizon he

saw, perhaps a quarter of a mile away, what looked like a fine

trickle of blackish smoke that appeared to rise from a shapeless

mound that bulged above the monotonous level.

“Smoke means fire, and fire means man,” he said, excitedly.

The sky was rapidly clearing. A few stars had already appeared.

Remembering what he had learned on camp and trail, he took his

bearing by the stars; he did not mean to get lost if he left that

hill. Looking back, he could see the car, the lamp of which sent

broad beams of light through the windows across the snow.

Then he plunged down the hill, thanking God in his boyish heart

for the snow-shoes and his knowledge of them.

It did not take him long to reach the mound whence the smoke

rose. It was a sod house, he found, built against a sharp knoll,

which no doubt formed its rear wall. The wind had drifted the

snow, leaving a half-open way to the door. Noiselessly the boy

slipped down to it, drew his feet from the snow-shoes and

knocked. There was a burst of sound inside. It made his heart

jump, but he was reassured by the fact that the voices were those

of children. What they said he could not make out; but, without

further ado, he opened the door and entered.

It was a fairly large room. There were two beds in it, a stove, a

table, a chest of drawers and a few chairs. From one of the beds

three heads stared at him. As each head was covered with a wool

cap, drawn down over the ears, like his own, he could not make

out who they were. There were dishes on the table, but they were

empty. The room was cold, although it was evident that there was

still a little fire in the stove.

“Oh!” came from one of the heads in the bed. “I thought you were

my father. What is your name?”

“My name,” answered the boy, “is Henry Ives. I was left behind

alone in the railroad car about a mile back, and saw the smoke

from your house and here I am.”

“Have you brought us anything to burn?” asked the second head.

“Or anything to eat?” questioned the third.

“My name is Mary Wright,” said the first speaker, “and these are

my brothers George and Philip. Father went away yesterday morning

with the team, to get some coal and some food. He went to Kiowa.”

“That’s where I am going,” interrupted Henry.

“Yes,” continued Mary, “I suppose he can’t get back because of

the snow. It’s an awful storm.”

“We haven’t anything to eat, and I don’t know when father will be

back,” said George.

“And it’s Christmas Eve,” wailed Philip, who appeared to be about

seven.

He set up a howl about this which his brother George, who was